Voices from the Past

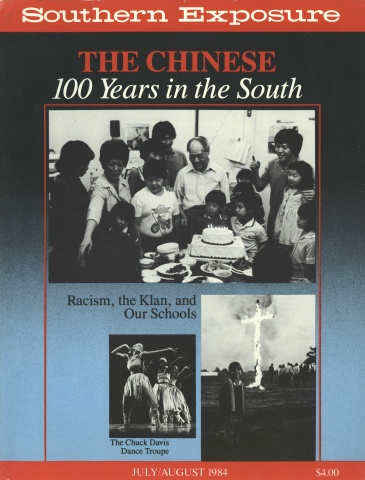

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 4, "The Chinese: 100 Years in the South." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Many people had their lives changed by their experiences in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. Barbara Deming, for four decades one of America's foremost writers on the issues of feminism and nonviolence was one. The following originally appeared in The Nation on May 25,1963, and is part of a new collection of Deming s writings, We Are All Part of One Another, edited by Jane Meyerding and published by New Society Publishers.

The day I went to jail in Birmingham for joining a group of Negro demonstrators — children most of them — who were petitioning, "without a license," for the right to be treated like human beings ("that's what it boils down to, that's all we ask"), I experienced more sharply than I ever had before the tragic nature of segregation, that breakdown of communication between human and human which segregation means and is.

The steps which took me from the Negro church in which I spent the early part of that day, May 6, sitting among the children as they were carefully briefed and finally, in small groups, one after another, marched, holding hands and singing, into the streets — "marching toward freedom land" — the steps which placed me swiftly then in the white women's ward of the city jail provided a jolt for the mind that can still, recalling it, astonish me. . . .

Now and then, when the wind was right, I could hear the children's voices from their cells, high and clear — "Ain't gonna let nobody turn me round, turn me round, turn me round. . . . Woke up this morning with my mind set on freedom!" — the singing bold and joyfill still; and with that sound I was blessedly in their presence again. I strained to hear it, to bolster my own courage. For now I was a devil, too, of course — I was a "nigger lover." The warden had introduced me to my cell mates, in shrill outrage, and encouraged them to "cut me down" as they chose. They soon informed me that one of the guards had recommended that they beat me up. No one had moved to do it yet, but the glances of some of them were fierce enough to promise it. "What have you got against Southern people?"

I was not an enemy of the Southern people, I answered as calmly as I could. I happened to believe that we really were intended to try to love every person we met as we love ourselves. That would obviously include any Southern white person I met. For me it simply also obviously included any Negro. They stared at me, bewildered, and I didn't try to say any more. I lay down on my bunk and tried to remove myself from their attention and to control my fears of them. . . .

As the days passed, I stopped fearing my cell mates and made friends with them. After a little while this wasn't hard to do. Every woman in there was sick and in trouble. I had only to express the simplest human sympathy, which it would have been difficult not to feel, to establish the beginning of a friendly bond. Most of the women had been jailed for drunkenness, disorderly conduct, or prostitution. That is to say, they had been jailed because they were poor and had been drunk or disorderly or had prostituted themselves. Needless to say, I met no well-to-do people there, guilty of these universal misdemeanors. A few of the women had been jailed not because they really had been "guilty" once again this particular time, but because they were by now familiar figures to the cops; one beer, the smell of it on her breath, would suffice for an arrest if a cop caught sight of one of them. The briefest conversations with these women reveal the misfortunes that had driven them to drink: family problems, the sudden death of a husband, grave illness. All conspicuously needed help, not punishment — needed, first and foremost, medical help. The majority of them needed very special medical attention, and many while in jail were deprived of some medicine on which they depended. One woman was a "bleeder" and was supposed to receive a blood transfusion once a month, but it was many days overdue. Each one of them would leave sicker, more desperate than she had entered; poorer, unless she had chosen to work out her fine. One woman told me that the city had collected $300 in fines from her since January. From those who have not shall be taken.

One day, in jest, one of the women cried to the rest of us when the jail authorities had kept her waiting endlessly before allowing her the phone call that was her due: "I ought to march with the Freedom Riders!" I thought to myself: you are grasping at the truth in this jest. Toward the end of my stay I began to be able to speak such thoughts aloud to a few of them — to tell them that they did, in truth, belong out in the streets with the Negroes, petitioning those in power for the right to be treated like human beings. I began to be able to question their wild fears and to report to them the words I had heard spoken by the Negro leaders as they carefully prepared their followers for the demonstrations — words counseling over and over not for the vengeance they imagined so feverishly ("They all have knives and guns! You know it!") but forbearance and common sense; not violence but nonviolence; I stressed for them the words of the integration movement's hymn: "Deep in my heart I do believe we shall live in peace some day — black and white together." One after another would listen to me in a strange, hushed astonishment, staring at me, half beginning to believe. By the time I was bailed out with the other demonstrators, on May 11, there was a dream in my head: if the words the Negroes in the nonviolent movement are speaking and are enacting ever begin to reach these others who have yet to know real freedom, what might that movement not become? But I was by then perhaps a little stir crazy.