The Klan Attack on Schools

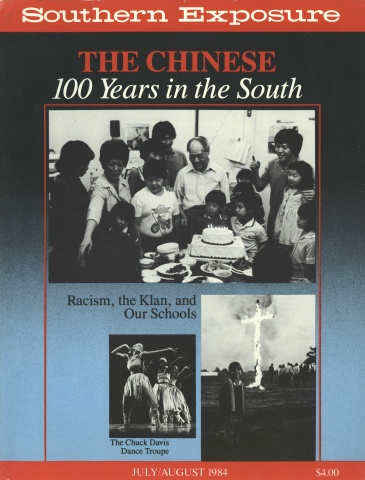

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 4, "The Chinese: 100 Years in the South." Find more from that issue here.

On January 17, 1984, Glenn Miller, Grand Dragon of the Carolina Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, walked into North Carolina Attorney General Rufus Edmisten's office with a written demand: if the state does not establish a "citizen's militia" to protect white school children from violent racial assaults, the Klan will do so.

Miller threatened, "1,000 white men will begin armed patrols in the areas of selected public schools in North Carolina," if the attorney general did not respond within 30 days.

That a Klan leader could target the public schools so boldly indicates both the strength of the Klan in the state and the failure of law enforcement and elected officials to take action against a growing crisis. The National Anti-Klan Network considers North Carolina's groups of Klans to be the most active and most dangerous in the country. Miller's faction is responsible for much of this rapid growth.

One of a new generation of media-wise Klan leaders, Miller is an expert at manipulating media coverage. Financed by his army retirement pay, he claims to work eight to 10 hours a day "for the rights of white people." And his farm in Johnston County hosts one of three Klan paramilitary training camps in North Carolina.

Present in the Klan/Nazi caravan that rode into Greensboro and killed five anti-Klan demonstrators on November 3, 1979, Miller switched from the Nazi Party to the Klan after the Greensboro massacre. Following the April 1984 acquittals of the men responsible for the murders, he proclaimed he would recruit "hundreds of thousands" of white people into the Klan.

Miller likes to present the Klan as a "law and order" organization. The state's failure to prosecute illegal Klan activity allows him to claim, "There hasn't been a Klansman convicted of a violent crime in North Carolina in more than eight years."

In his January 17 memo delivered to David Crump, the state's deputy attorney general, Miller set himself up as protector of white children against violent blacks: "White-on-Black crimes of violence in our schools are virtually nonexistent, while Black-on-White crimes of violence is [sic] rampant and indeed, out of control. Simply [sic] crime statistics proves that North Carolina's law enforcement agencies can not, and are not controlling violent crimes against White school children. This rampaging racist violence directed against White school children will no longer be tolerated by the White citizens of North Carolina. We will act to protect our own children."

The Klan's century-long history of lawlessness — hanging, branding, castrating, lynching, tar-and-feathering, dynamiting, clubbing, raping, fire-branding, and shooting make such law-and-order posturing ironic to those familiar with Klan history. A look at the Klan's disruption of public education in North Carolina in 1984 shows that in most cases the violence and provocation come from racist whites.

The immediate inspiration for Miller's statewide school campaign came from Ronald Reagan. The President released a report on "Disorder in Our Public Schools" in early January. On January 7, Reagan told a national radio audience that "we can't get learning back into our schools until we get the crime and violence out." Nationally, educators immediately disputed the President's conclusions. According to Scott Thomson, executive director of the National Association of Secondary School Principals, discipline problems are "nowhere near as bad as they were five years ago — there has been an important swing in student and parent attitudes." Educators explained that the national figures cited in the President's report were gathered by the National Institute of Education between 1975 and 1977. In a National Education Association survey of its members in 1983, only 45 percent of the teachers questioned thought that discipline was a major problem, against 74 percent in a 1979 survey.

In the weeks prior to the March 5 deadline for Miller's threatened Klan school patrols, various state agencies made some preparations. It was clear that the Carolina Knights could not put 1,000 armed men near public schools, or even 100. But any armed Klansmen threatening children could be dangerous. The attorney general's office was faced with trying to minimize the publicity Miller was getting — one of his chief goals — while working to head off any trouble that might occur.

At the request of the state's Human Relations Council, executive director Gene Causby of the North Carolina School Board Association sent out a memo on February 27 to county school boards. Alerting them to the possibility of Klan activity in the school system, Causby's memo provided information about the legal steps school officials could take to counter the Klan. The attorney general's office also issued instructions to local law enforcement officers reminding them of these same laws.

In Durham County tensions rose. Members of the United Klans of America had plastered recruitment posters all over the north half of the county in February. Black children came home from school asking, "Who is the Klan? Will they get you?" Rumors were rife all over town until the principal of Durham High School called an assembly to explain the situation and to reassure students of their safety. Said one parent of a Durham High teenager, "The students were very upset. I was not just concerned, but outraged. I was prepared to go and sit in at the school for a week, but my daughter asked me not to. She felt that the principal, who is black, could handle it if they did show up."

The March 5 deadline also presented Miller with a problem. Clearly he was bluffing with his numbers. The "massive White march, rally, and demonstration" he had called for March 4 in downtown Raleigh never materialized. But he continued the bluff. The week before the deadline, he announced that Klansmen would drive by schools in unmarked cars and only make themselves known if they saw acts of violence, in which case they would make citizen's arrests. This plan allowed Miller to claim on March 6 that 3,000 to 5,000 Klansmen and sympathizers were patrolling near schools.

Attorney General Edmisten's office checked with several law enforcement officials and school administrators and turned up reports of Klan activity in only one place. In Sanford, according to school superintendent William Johnson, two cars containing men dressed in battle fatigues drove onto the school bus driveway at Lee County Senior High, then quickly drove off. Two cars also rode by W.B. Wicker School in Sanford; occupants yelled something unintelligible and drove off. Later, reports unconfirmed by the Attorney General's office placed Klansmen near schools or on campuses in Chapel Hill, Raleigh, Durham, and Wake Forest.

While Glenn Miller's March 5 statewide threat worked mainly for purposes of publicity and intimidation, since that date, Klan disruption has plagued schools in at least three North Carolina counties. In each case, briefly described below, the school's experience presents lessons: if local government, law enforcement, and school officials do not clearly and quickly make it known that the Klan is not welcome, the tensions within the schools — the same tensions the Klan seeks to exploit — will continue to fester. And when public officials and the general citizenry do not organize against the Klan, parents will.

Lee County

Lee County's Sanford schools have experienced the most harassment by adult Klansmen in the past year. By and large, school officials and community leaders have handled the situation well. Miller's January demands to the attorney general were inspired in large part by his experiences in Lee County, one of the Piedmont counties where his Carolina Knights are most active. On November 15, 1983, a white girl was raped at W.B. Wicker Middle School, and a black man was charged with the crime. Three days later, a Klan delegation that included Miller visited Sanford Mayor Rex McLeod, asking permission to allow an armed Klansman to patrol the grounds and hold "safety" classes for whites only. "I didn't appreciate it," McLeod said of the Klan visit. The next week, the Lee County School Board decided to hire a security guard for the school. Miller praised the guard as a "step in the right direction."

The next week, racist organizing in the county claimed a life — that of a Klansman. On November 20 Miller's Klan held a rally in Silk Hope. After Miller left, Lee County den leader James Holder got into an argument with Chatham County den leader David Wallace, and Holder shot Wallace. The argument was over whether or not to hold a demonstration against the schoolgirl's accused rapist, then being held in the Lee County jail.

(It wasn't the first time Holder, who had been active throughout the year as a Klan organizer, had caused trouble. In February 1983 Holder, who worked at an Econo-Lodge Motel in Sanford, was fired for giving a KKK calling card to a black customer at the motel, and the Klan held a protest rally in front of the motel two months later.)

In April, trouble flared up again after men were found hiding in school bathrooms on three separate occasions. On April 4, 16 Klansmen in fatigues demonstrated at the police station, where the police captain refused to receive a Klan letter threatening patrols if McIver Elementary School did not provide a full-time guard. Miller called for white children to boycott McIver on April 16. School officials responded to the security problem by hiring a guard, while parents began monitoring the halls and rest rooms. Approximately 17 percent of McIver's students stayed home Monday, April 16, double the normal absentee rate. After reviewing attendance records, Superintendent William Johnson said that most of those absent were black students — a clear indication of Klan intimidation. When a white teenager came onto school grounds in fatigues, he was immediately arrested for trespassing.

In Lee County the Klan continues to be a problem to the county's school children and school officials. But elected officials, school officials, law enforcement officers, and parents have acted together to deal with local problems and the extra problems the Klan has created. "The Klan is trying to use this as a racial thing and it's not," said Libby Johnson, a parent who patrols at McIver.

Onslow County

In coastal Jacksonville, as in Sanford, Miller's Klan tried to exploit problems within a school. Trouble at Dixon Senior High School started when white students passed around a racist joke. Black students were insulted, and their verbal protests were "loud and upset, though not violent," according to white principal James Rochelle. He suspended students who violated the school's rules against weapons and fights: four whites and one black for carrying knives, and a black and a white student for fighting.

When Leroy Gibson, longtime Carolina racist troublemaker and a resident of Onslow County, heard about the suspensions he moved in to "protect" the white students who, he said, were being treated unfairly. (Here is an example of Klan/racist logic: black students are more violent, but when three times more white students are expelled for violence than blacks, then white students are being persecuted.)

Gibson called for a Klan rally near the school and Rochelle responded by making a strong statement to the press about not wanting the Klan involved in his school's affairs. If Klansmen appeared on the campus, Rochelle said, they would be asked to leave. If they refused to do so, they would then be arrested and charged with trespassing and disturbing the normal activity of public education. Both black and white students at the school made it clear that they did not desire the help of the Klan and Gibson's threatened rally never materialized.

Rowan County

At the close of the school year, West Rowan High School in Salisbury presented the most volatile situation in the state's public schools. This case illustrates how racial tension can escalate when school administrators and local officials do not take strong stands against the Klan and Klan-related activity.

Tensions started at the beginning of the school year when two black male students with white girl friends received letters threatening Klan action if they continued to date the girls. When the students went to take the letters to the office, someone painted "KKK" on their lockers. Two white students were suspended for 10 days for this action.

Racial tension at West Rowan peaked in mid-March, according to an article in the Salisbury Post, when one hundred black and white students squared off in a shouting match in the school's courtyard. The near-riot grew out of an incident where a white student blocked a black classmate from going through a door. The two later got into a fight at an evening movie. The white student started the fight. The following day, a white student threatened that Klansmen would be at the school the following week to "resolve" the problem. Rumors of a Klan school patrol spread through the black community, upsetting many parents.

Their response was spearheaded by a black parents' group, Concerned Parents, which had formed the previous May to seek better representation of blacks on West Rowan's band, cheerleading squad, and other school organizations. Mrs. Essie Hogue, spokeswoman for the group, said, "We felt like if the Klan is going to come to West Rowan, that they'll also invade other schools in the area." Members of Concerned Parents received an alarming number of calls from black students who believed that white students were trying to recruit Klan members in the schools. "It can't be isolated when you've got this many reports going on," Hogue said. And the Salisbury Post quoted the parent of a son victimized by racial slurs, "He has reached the point where he virtually despises the place, and I know he's not alone."

The trouble at West Rowan High can be traced to an organized gang of white students called the "Bannys," named after the bantam rooster because of their cocky attitudes. Although the Bannys deny it, there are indications that they are Klan-influenced. Black students have seen Banny members talking with known Klansmen, and white students have warned black students that the Bannys are indeed the Klan.

While much of the trouble at West Rowan originates with Banny activities, the presence of robed adult Klansmen on the Methodist Church grounds across from the school on March 28 exacerbated the already volatile situation. One of these Klansmen reportedly stepped in front of a school bus and tried to make the driver, a black female student, take Klan literature. The Associated Press reported that in the group was the White Knights of Liberty Grand Dragon, Joe Grady. Six black and two white students left school that day; three students were suspended, one white for writing KKK on the wall, and one white and one black for racial slurs.

Various forms of harassment continued. Toward the end of the year a white student drew a picture on a black student's test paper of a robed Klansman, a burning cross, and a black splotch. Along with the drawing was the note, "This is your grave." In addition, a white basketball player who had a black friend came down to the locker room to find a note hanging over his locker saying: "If you don't stop hanging around with blacks, you will meet bodily harm."

At least 22 students have been suspended since the March public meeting of the Concerned Parents. Despite these suspensions, Concerned Parents feels that the school administration and the county school board have not taken strong enough action to counter the problems at West Rowan High. Nor, they feel, have the disciplinary actions been fairly distributed between black and white students. Concerned Parent Hogue says that attention from outside groups such as the state Human Relations Council has helped bring the situation more under control and they have asked to appear before the school board at its June meeting.

These three cases alone illustrate an alarming trend in North Carolina's schools. Yet they are perhaps only the tip of the iceberg. State officials have on the whole failed to treat the resurgence of the Klan in North Carolina with the seriousness it deserves. "Moderate" North Carolina politicians such as Governor James Hunt and Attorney General Rufus Edmisten — who are running for the U.S. Senate and governor, respectively, in 1984 — have not taken strong stands against the wave of Klan intimidation and violence that has crested during their administration.

Hunt, locked into a race with Jesse Helms for the U.S. Senate, is playing it safe for conservative votes. Edmisten won the Democratic nomination for governor, but now must face a strong challenge from Republican Jim Martin. Both have referred the problem back to local law enforcement and elected district attorneys in the state's 35 court districts. According to Don Stephens, of the special prosecutions division of the attorney general's office, "Our office has not been requested [by any district attorney] to assist, participate, or handle cases involving Klan violation of the law in at least six or seven years."

In these districts with original jurisdiction over Klan offenses, law enforcement often appears either apathetic or sympathetic with the Klan. In Johnston County, the sheriff participated in a Carolina Knights of the KKK parade. In Iredell County, lawmen allowed 15 robed Klansmen from Joe Grady's White Knights of Liberty into the jail to offer to "bond out" a black man accused of raping a white woman. Generally, local law enforcement officials view cross burnings as "pranks," and thus avoid prosecution under a state law prohibiting cross burnings for the purpose of intimidation.

In view of the state's inactivity, Miller's boast about the lack of convictions of Klansmen becomes not proof that his group is law-abiding, but an indictment of state and local law enforcement.

In light of this lack of prosecution of illegal Klan activities, citizens should know what laws are on the books to protect children and their parents from Klan harassment. The North Carolina School Board Association's February memo cites several statutes which school officials can use against Klan school patrols.

Under criminal law statute G.S. 14-288.4, a person can be convicted for disorderly conduct if he "refuses to vacate any building or facility or any public or private education institution in obedience to an order of the chief administrative officer of the institution." An intruder can also be convicted if he "disrupts, disturbs or interferes with the teaching of students of any public or private educational institution or engages in conduct which disturbs the peace, order or discipline at any public or private educational institution or on the grounds adjacent thereto."

Under section 14-288.5, a law enforcement officer may command citizens to disperse if he "reasonably believes that a riot, or disorderly conduct by an assemblage of three or more persons, is occurring." Any Klan member or supporter found possessing a weapon on a school campus can be convicted of a misdemeanor. Maximum penalties for these offenses are fines of $500 and imprisonment for six months.

To offer students effective protection, these laws require the cooperation of both local police and school administration. There is also a state law (127A-151) against organizing a military company without authority: "If any person shall organize a military company, or drill or parade under arms as a military body, except under the militia laws and regulations of the State, or shall exercise or attempt to exercise the power or authority of a military officer in this State, without holding a commission from the Governor, he shall be guilty of a misdemeanor."

Given these laws, many people are asking: when Glenn Miller threatens to usurp the police function of the state government if public officials do not comply with his demands; when he has a paramilitary training camp on his land and appears with men in fatigues and parades with uniformed men — hasn't he organized a private army? When asked about this statute prior to Miller's March 5 deadline for the school Klan patrols, an official in the attorney general's office replied, "We are looking at it."

That organizing a private army is a misdemeanor indicates the weakness of the legal protection against Klan intimidation. Jim Bowden of the North Carolina human relations council supports the need for state anti-Klan statutes to be reviewed and updated: "For people to intimidate other people without fear of reprisals beyond a $50 fine is a farfetched situation."

Federal laws also protect public education — 18 U.S.C. 245 makes it a federal crime to "by force or threat of force willfully injure, intimidate, or interfere with . . . any person because of his race, color, religion or national origin and because he is or has been . . . enrolling in or attending public school or public college." When Miller calls for a boycott by white students and threatens Klan patrols and as a result double the normal number of students stay away from school, is this not intimidation? Or when six students leave West Rowan High because the Klan is leafletting next door, hasn't their right to attend public school been threatened?

Unwilling to wait until Klan harassment escalates into serious injury or death to North Carolina school children, a coalition of educators, state agencies, and activist groups are planning a statewide conference in September. As the state's schools close for the school year, almost exactly 30 years to the month after Brown v. Board of Education, the struggle to give black children equal access to quality education continues.

Tags

Mab Segrest

Mab Segrest is a writer, teacher, and organizer who lives in Durham, NC. She has written two books, My Mama's Dead Squirrel and Memoir of a Race Traitor. She is working on a third, Born to Belonging. This is excerpted from an essay that appeared originally in Neither Separate Nor Equal: Race, Class and Gender in the South, edited by Barbara Smith (Philadelphia: Temple, 1999). (1999)