Romantic Appalachia

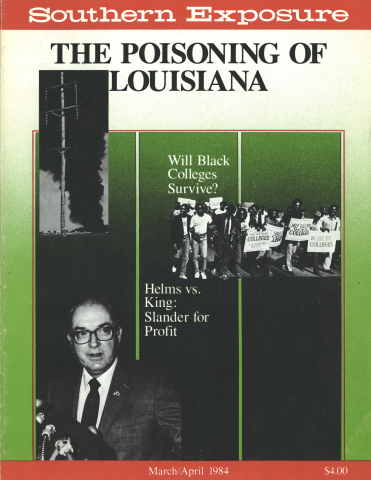

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 2, "The Poisoning of Louisiana." Find more from that issue here.

Almost every day we get letters from those wanting to come to Appalachia to "fight poverty." They've seen movies, comic strips or TV (Lil' Abner, Beverly Hillbillies). It's not that there's no poverty in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Chicago and other parts. There is. But Southern Appalachia has that "romantic" appeal.

So we are "discovered" again. It's happened every generation, sometimes more often, since the Civil War.

Yes, the Southern mountains have been missionarized, researched, studied, surveyed, romanticized, dramatized, hillbillyized, Dogpatchized, and povertyized again. The latest "missionary" move is the "War on Poverty." It was never intended to end poverty. That would require a total reconstruction of the system of ownership, production and distribution of wealth.

This is not the first time in our lifetime that big city folks have come down to save and lift us up. I remember the 1920-1930s. Southern Appalachia was discovered then, too. Young "missionaries" were sowing their "radical wild oats" from the Black Belt of Alabama and Arkansas to Harlan County, Kentucky, and Paint and Cabin Creeks in West Virginia. They were mostly transients, as "missionaries" frequently are. I don't know a single one who remained.

There is a qualitatively different situation for those who come to fight poverty in Appalachia now and back in the 1930s. Then they came on their own. There was no OEO, no VISTA, no Appalachian Volunteers. Nobody was paid a good salary to fight poverty. They made their own way, shifted as best they could. It was Depression times, too. Some did good work. Some were murdered by thugs. Others were beaten, crippled. Issues were sharp and violence was too common. They who worked at organizing the poor had to keep a wary eye.

But things are considerably different now. The young "missionary" in Appalachia has it comparatively easy. First, he is paid. He has food to eat regularly, a place to sleep. He goes to bed with scant fear of being murdered in his sleep. And in an area where tens of thousands of families live on less than $2,000 a year, poverty fighters may get much more. Some salaries are large — $10 thousand, $15 thousand, $20 or $25 thousand or more.

Some of the bright young "missionaries" who came down in one of the poverty-fighting brigades, perhaps despairing of saving our "hillbilly souls," certainly failing to organize the poor, now find money in poverty by setting up post office box corporations that receive lucrative OEO grants or contracts to train others to "fight poverty." If they failed to organize the poor themselves, they nonetheless can train others to go out and do likewise.

So many do-gooders who come into the mountains seldom grasp the feet that the poor are poor because of the nature of the system of ownership, production and distribution. When the poor fail to accept their middle-class notions they may end up frustrated failures.

Their basic concern was not how they related to the mountains but how the mountains related to them and their notions. With their "superior" approach, they failed to understand or appreciate the historic struggles of broad sections of the mountain people against the workings of the system back beyond the 1930s. And before that the mountain man's struggle against a slave system that oppressed both the poor white and black slaves.

The "missionaries" — religious or secular — had and have one thing in common: they didn't trust us hill folk to speak, plan and act for ourselves. Bright, articulate, ambitious, well-intentioned, they became our spokesmen, our planners, our actors. And so they'll go again, leaving us and our poverty behind.

But is there a lesson to be learned? I think so. If we native mountaineers can now determine to organize and save ourselves, save our mountains from the spoilers who tear them down, pollute our streams and leave grotesque areas of ugliness, there is hope. The billionaire families behind the great corporations are also outsiders who sometimes claim they want to "save" us. It is time that we hill folks should understand and appreciate our heritage, stand up like those who were our ancestors, develop our own self-identity. It is time to realize that nobody from the outside is ever going to save us from bad conditions unless we make our own stand. We must learn to organize again, speak, plan, and act for ourselves. There are many potential allies with common problems — the poor of the great cities, the Indians, the blacks who are also exploited. They need us. We need them. Solidarity is still crucial. If we learn this lesson from the outside "missionary" failures, then we are on our way.

Tags

Don West

Don West's recent collection of poetry and prose is reviewed on page 64. It includes the full text of his 1968 essay "Romantic Appalachia — or Poverty Pays If You Ain't Poor," which is condensed here: strong words for the poverty warriors and other outsiders who periodically invade the Southern mountains. (1984)