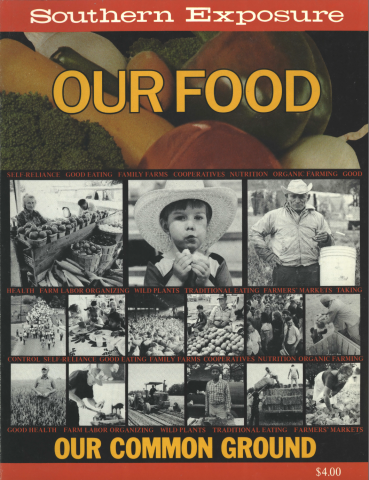

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 6, "Our Food." Find more from that issue here.

“As medicine moves toward the twenty-first century it is being transformed into a holistic model, emphasizing health promotion and disease prevention. Within this model nutrition will play a major role in re-establishing the balance of health and well-being.” - James H. Carter, Jr., M.D. Atlanta

Dr. James Carter is an assistant professor of family and community medicine at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, and medical director of the Center for Preventive Medicine. As a teaching professor and health care practitioner, Dr. Carter advocates and employs a holistic approach incorporating nutrition in the prevention and treatment of illness. Dr. Carter recently spoke to Southern Exposure editor Christina Davis about preventive medicine and self-reliance in community health care.

In preventive medicine, the important premise is that health is not something the doctor gives you, it is something you can have and control personally.

I graduated from Howard University School of Medicine, did my internship at Harlem Hospital, and returned to Howard for my residency in family practice. To deal with what I was seeing every day, I began to search for more than the skills and training I had as an acute-care physician. People came into the hospital with varying degrees of chronic illness and disease and left with literally bags of pills and the absence of health.

As I watched this, I became interested in ways to intervene before wellness was beyond recovery. Naturally, this set me on the course of taking a look at the whole system of health. The essence of the holistic approach to medicine involves dealing with all the elements in the system — physical, social, mental, and spiritual — and exploring nutrition, because nutrients are the basis of the formation of cells and tissues. Our closest link to the environment is through nutrition.

When I went to Tuskegee, Alabama, to do two years of work in public health, I was introduced to a rural community. While there, I received a grant to do some work in this community from the Wheatridge Philanthropic Organization, located in Chicago. As a result, an experimental two-year project, called the Center for Holistic Health and Wellness, was started. There were real challenges and resistance in this setting. And, even though there was a community advisory board and an educational program going on in the schools and community, because of misconceptions the center drew criticism from many organizations. Also, other physicians in the community did not readily support the center because it focused on alternatives to medication and surgery and took a basic look at lifestyles, patterns, and habits to promote wellness.

The center failed to remain open much beyond the two-year pilot period. This was largely due to fears of “mysticism” surrounding holism, reluctance on the part of the community as a whole, and the lack of available resources to continue this type of program in a rural setting. But for me it was the basis for a lot of learning and continued research in the area of nutrition therapy and preventive medicine.

Comparing the rural Alabama setting with my earlier experiences in urban settings, I discovered that the average American diet is high in fat, sugar, salt, and processed foods with assorted chemicals. Such a diet predisposes one to multiple vitamin and mineral deficiencies that in turn lead to chronic degenerative diseases — heart disease, cancer, hypertension, diabetes, and so on. Even when one considers disparities among us, rural and urban, access and isolation, poverty and affluence, black and white, heredity and culture, we are all subject to and products of this fast-food culture. And I have found that the greatest degree of resistance to dietary changes is met from patients who refuse to give up adopted and learned, yet unhealthy, patterns of eating. Rich and poor alike are dying from the same diseases.

Preventive medicine and the use of nutrition therapy in the prevention and treatment of illness are not new. Practiced for centuries in Africa, where medicine had its genesis, preventive medicine was first taken up by segments of the American medical profession as early as the turn of the century, and it flourished during the 1920s and ’30s. Resistance then, as now, came from the scientific community as the influence and control of the petrochemical and pharmaceutical interests increased.

The use of the term “holistic” also conjured up in the minds of many individuals images of mysterious and “unscientific” healing techniques, many of which can be traced to their sources in ancient Africa, especially within the mystery schools of Egypt. Orthodox Western physicians have not even begun to fathom the knowledge and wisdom of these ancient healers. The fact that the dynamics of the universe and other spiritual factors are a part of medicine in the holistic spectrum brought challenges from many critics. In addition, the advent of the industrial revolution fostered a fascination with machines and gadgets and resulted in the dehumanization of medicine. Thus, the focus on medications and surgery - the mainstay and fabric of today’s $287 billion health care industry — forced preventive medicine into an inner circle and out of the reach of many needy individuals.

But in the 1960s and ’70s, preventive medicine became a real concern, and it is even more prevalent in the ’80s. This is evidenced by the focus and direction of public health at the black medical schools, Howard, Meharry, and Morehouse. There is now a recognition of the need for a new concept of teaching in medicine, particularly for prevention. Teaching doctors to be more aware of human alternatives to the treatment of disease is one focus. Along with this, there is an attempt to incorporate into medical school curricula nutrition education and psychosomatic medicine, heretofore missing dimensions in medical training.

And, while there is some concern that not enough doctors and other health-care practitioners are coming out of today’s schools, when we consider the increase in the number of doctors over the last 10 years, I have to disagree. What is needed is for more health-conscious practitioners to change the values of today’s medical system — and commit themselves to development of community-based preventive medicine centers where people are taught how to be healthy and how to maximize their human potential.

Put the people directly in charge of their health and wellness. I do not say that there is no need for hospitals; what I’m saying is people need to know that they have the skills to keep themselves healthy. Then the major role of the practitioner becomes that of educator — providing a one-to-one level of consultation, teaching how current lifestyle patterns conflict with health and good nutrition, and developing maintenance plans to minimize the degree of professional intervention.

Health is not something the doctor gives you, it is something you develop and maintain by the way you think and live. It is this premise that we operate from at the Center for Preventive Medicine, and it’s the teaching philosophy we apply at Morehouse. And so, to develop a wellness prescription, when new patients come to visit the center, we first discuss with them hereditary patterns of illness, risk factors, stress, environmental considerations, and other physio-social factors to determine problems that exist and the potential for others.

Next, we do a nutritional evaluation using computerized analysis to provide a breakdown of what patients consume and deficiencies in their diet. This is an indicator of the kinds of changes they must make nutritionally. Then we jointly design an exercise program tailored to the tolerance level and needs of the patient, and teach stress management techniques. Finally, we discuss and decide upon a maintenance program. This is based on another premise, that health is a state of choice and is contingent upon maintaining a balance with nature. And it is really remarkable; when people are given these basics and understand their choices, they opt for greater health through their own participation.