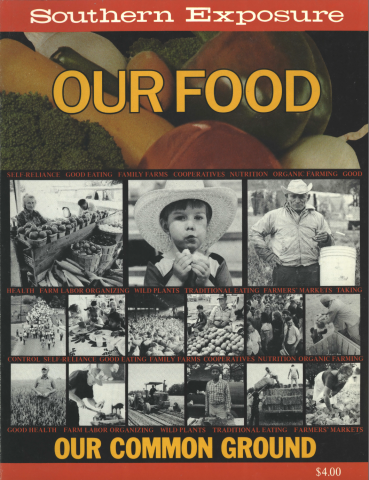

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 6, "Our Food." Find more from that issue here.

The Florida sun had not yet risen, as we - sleepily made our way past the endless miles of sugar plantations and cane fields. It was 4:30 a.m. on a cold January day. The nearby towns along the shore of Lake Okeechobee still seemed blanketed in sleep, unconscious of pre-dawn stirrings.

Shape-Up

Under the cover of night, dusty white vans and tattered old school buses hurried through the quiet darkness. Huddled groups of bundled bodies wearily shuffled along the side of the road, like co-conspirators in some prearranged plan. As we sped by in our rented station wagon, we knew we were nearing Belle Glade, Florida, the home base of the Eastern farmworker stream.

This was to be our last day in Florida, after a week visiting farmworker groups up and down the state. Seven of us, three blacks and four whites, representing various churches and farmworker groups in North Carolina, had journeyed south to learn more about the home base of the estimated 40,000 workers who migrate north each harvest season to our state. Before leaving Florida, we decided to witness the Belle Glade “shape-up,” the early morning recruitment of day workers by farm labor contractors. Jobs go to those who will take the least pay for the “privilege” of doing back-breaking labor under the steamy Florida sun.

What we saw and heard during the next several hours left us all with lingering, disturbing impressions. One of us referred to this daily recruitment ritual as a “conspiracy of darkness.” To another, it was the “open buying and selling of human beings in a slave market.”

Hundreds upon hundreds of people of color - women, men, young, old, black-American, Hispanic, and Haitian — gathered at the town square. The labor contractors they met wanted only enough workers to fill the vacant seats in the vans and buses. Many workers secured another day’s employment; many more were not so lucky.

All are players in this game of chance. The stakes are high and immediate — day-to-day survival. Of those left standing in the square, some passed it off with comments like, “I didn’t want to work today anyway.” Somehow, though, we knew they would be back tomorrow — and the next day, and the one after. Even the sick, the injured, and the elderly would return despite the daily disappointment. Not a one could afford to give up the chance of one day’s work.

By the time the first shafts of sunlight spread across the square, the marketers of human flesh had vanished. Their vans and buses creaked wearily toward the fields, as if sympathetic to the silent resignation of the passengers inside. Not until much later that evening, after the blistering sun had retired, would these workers return to their homes, only to rest up for the following morning when the ritual of trade in human labor would be repeated.

In the meantime, the rest of the country would wake up and go about its business, enjoying the fruits of farm labor at each meal, oblivious to the slave-like conditions of the harvest.

People in the System

Who are these workers huddled in the early morning darkness of Belle Glade? They are some of the more than five million agricultural workers in this country who form an invisible, ever-mobile work force. They are some of the 1.5 million workers who yearly labor on farms in the Eastern migrant stream. They are also part of the agricultural work force of the South, whose 13 states account for 50 percent of the nation’s agricultural labor pool. California has the most, but the Southern states of Texas (second), North Carolina (third), Florida (fourth), and Georgia (sixth) account for an enormous percentage of the farm work force. The pattern of small black farms and of large white farms which hire mainly local or migrating black farmworkers still persists in the South. Both the Western and Midwestern migrant streams are dominated by Hispanic farmworkers, but more than 60 percent of the Eastern stream’s workers are black.

For migrant workers in Belle Glade’s morning market, the trip up the coast begins in the early spring, after the winter citrus and vegetable crops are harvested in Florida. The trip up the migrant stream is not an unplanned flow. Federally licensed farm labor contractors recruit crews usually numbering 25 to 30 workers. Most crews have work laid out for them in advance, averaging two to four stops over a six- or eight-month period. One crew may pick peaches in Georgia and South Carolina, and then jump to New Jersey to pick apples; another may go directly to North Carolina, moving from fields of green peppers to cucumbers to sweet potatoes before returning to Florida.

Many of the crewleaders, both “freewheelers” and those placed with growers under the aegis of the federal employment service, continue to work year after year with the same growers and farming corporations. Growers carefully limit their legal responsibility for the workers in their fields by “contracting” with these “independent” crew bosses to deliver a certain level of production at the end of a day or week. How the crewleader gets results is his problem.

The grower may own the barracks where workers sleep, and be required by law to pay a production rate equivalent to the federal minimum wage of $3.35 per hour; but he will also claim that what happens inside the labor camp, and what an individual worker receives as net pay after deductions by the crewleader, are “none of my business.” It’s a system that attracts the ruthless, breeds corruption, and thrives on disunity among workers.

While the growers in this system are virtually all white, crewleaders are generally of the same race as their crews. The various ethnic and geographic groups of workers are routinely pitted against each other to keep fear of job loss high and wages low. Southern agriculture now relies on a hodgepodge of laborers to plant and harvest its bounty: Hispanic, black, and white migrants; local “seasonal help,” primarily blacks; legally imported Jamaicans, Puerto Ricans, and Haitians; and illegal aliens, mainly from Mexico.

As we will see, the federal government is intimately involved in this unique system of labor-management relations by acts of both omission and commission. By not even collecting the data necessary to expose how the system works, the government effectively thwarts new policy initiatives that could attack the exploitation of farmworkers at its roots. But the statistics that do exist offer a startling picture of the effects of this “conspiracy of darkness” on five million human beings:

· Life expectancy of the average U.S. farmworker is 49 years, compared to 73 years for the population as a whole.

· Median family income for a migrant family of six — often with children working - is $3,900 per year - less than half of the official family poverty level of $9,287 and less than one-fifth the average family income of $22,388.

· 86 percent of migrant children fail to complete high school, while only 25 percent of all U.S. children drop out.

· Farm work is extremely hazardous, with the third highest death and serious injury rate of all occupations; farmworker families face a disability rate that is three times the national average.

· Of the estimated 10,000 migrant labor camps in the nation, only a few can meet basic federal safety and health standards.

Whether they sleep in boarding houses in town or in isolated labor camps in the middle of nowhere, farmworkers generally live in deplorably crowded, unsanitary quarters where communicable diseases run rampant. It is not uncommon for 40 people to share one or two pit latrine outhouses, outdoor slop sinks, and showers. Occasionally, a camp will have no sanitary facilities at all.

Although they pick the food which nourishes the rest of us, many farmworkers are fed barely enough to sustain themselves. The day’s meals typically consist of a plate of grits for breakfast, bologna on white bread for lunch, and chicken necks or fatback with rice and greens for dinner. Exorbitant food costs, running $40 to $45 a week, are deducted from each worker’s pay. The available beverages are usually alcoholic; beer and wine are illegally resold in the camps for two and three times the usual cost — another tool for keeping workers in debt and under control. Access to food stamps is also dependent on the crewleaders, and in most cases any benefit derived from their use does not go to the workers.

Working conditions in the fields are no better than living conditions in the camps. Farmworkers are frequently exposed to dangerous pesticides in the form of chemical residues on the crops or drift from the spraying of adjacent fields; sometimes farmworkers are directly sprayed in the fields and in the camps. Many times the pesticide residue run-off contaminates nearby drinking water supplies.

In most fields of the South and the East Coast, there are no toilets for workers to use during dawn-to-dusk workdays. Clean, cool drinking water and handwashing facilities are seldom available. In addition to the highly communicable diseases like tuberculosis which breed in close, unsanitary living quarters, the work itself is often physically debilitating and rapidly takes its toll on workers’ bodies.

Access to health care is severely limited for workers who must rely on their crewleaders for a ride to a clinic. As with everything in a migrant labor camp, there is always a steep charge for transportation. Moreover, visits to a clinic require that workers take time off from work. And since workers must often meet a production quota before they are fed, the loss of a day’s pay can also mean going without food.

Why do workers tolerate such living and working conditions? One principal reason is that once inside the system, they can’t escape because they immediately find themselves in perpetual debt to the crew boss, beginning with a stiff fee for the transportation to their first job. The alleged costs of all food, lodging, alcohol, drugs, and other services are always deducted from a farmworker’s weekly pay, often resulting in a “balance due.”

Once in debt, workers are told they cannot leave the camp until their debt is paid in full. Yet the longer they stay, the deeper they fall in debt. Nightly dog patrols, as well as threats, violence, and intimidation by the crewleaders and their henchmen, keep people from “escaping.”

Federal law says a condition of peonage or involuntary servitude exists when workers are prevented from leaving the labor camps by threats or acts of violence for real or imagined debts. For thousands of workers in the South, and up the Eastern stream, peonage is a daily reality, as several slavery trials in the last few years have graphically demonstrated. Workers can be caught in this psychological and physical form of slavery until the day they die. For some, the experience of labor camp life is so dehumanizing and radicalizing that they take great risks to escape. For others who vow to get out, the system is too strong, the alternatives too elusive, and the support from public or private agencies too tenuous to make freedom a realistic possibility.

Uncle Sam as Crew Boss

Large pools of unorganized low-wage farm laborers continue to be available to growers because of federal government policies that have evolved over the last 50 years. Despite the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment - which abolished slavery, peonage, and involuntary servitude — federal programs today are designed to protect the labor needs and profits of large growers, rather than the welfare of farmworkers. That bias is the essential key to understanding the modern farm labor procurement system.

As early as 1901, the U.S. Industrial Commission noted the importance of migrant workers to U.S. agriculture by reporting that “colored labor from the South was being used in New England states and that migration from crop to crop and area to area was an established pattern involving thousands of workers.” During the 1920s, winter vegetable and sugar cane growing areas were developed in Florida, making the state a focal point for off-season migration of workers from neighboring states.

Workers displaced by farm bankruptcies, bad crops, and machines during the Great Depression swelled the ranks of itinerant farm laborers. The cornerstone of the New Deal response, however, focused on farm income and production. The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933 paid growers to plow under a portion of their cotton fields to reduce the surplus and increase prices on the remaining crops. The law said growers must pay a percentage of the government subsidies to their tenants and sharecroppers. But that part of the AAA was rarely enforced.

In 1934, H.L. Mitchell and Clay East organized the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU) in Arkansas to demand their fair share of government payments to cotton growers. By organizing rank-and-file farm laborers and by generating national attention for their plight through trips to New York and Washington, the STFU increased political pressure for legislation to help the unemployed and under-employed agricultural workers.

The Wagner-Peyser Act of 1933 set up a national employment service through the U.S. Department of Labor, and it soon became the main mechanism for moving farm tenants, mostly blacks, to states with agricultural labor needs. But Southern growers also wielded considerable political clout during the New Deal. In a legislative deal to win support from key Southern senators, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 specifically excluded agricultural workers. These two laws established the basic structure of workers’ rights to bargain collectively and to enjoy federally mandated minimum standards for wages and working conditions. The legacy of being written out of these laws still haunts farmworkers today.

Growers also effectively turned the Wagner-Peyser Act into a system that legitimized the recruitment of migrant laborers through crew leaders. Under the Act, state employment security commissions were supposed to issue “interstate clearance orders” to growers who proved they could not find sufficient workers from their local areas and who pledged they would meet minimum standards for working conditions. As later court decisions demonstrated, these provisions of the Act quickly gave way to a system in which one state employment security commission routinely contacted another with an individual grower’s labor specifications, including the names of “preferred crewleaders” and the number of workers required, length of employment, and rate of pay.

Before World War II, about 25,000 black Southern workers moved along the Eastern stream each year; that number rose to 58,000 by 1949. As the use of migrant labor increased, growers, their associations, and government officials began holding conferences on ways to control the mobile work force more efficiently. In 1944, farm supervisors from 10 Atlantic Coast state agricultural extension services met in Raleigh, North Carolina, and established the first cooperative rural manpower program. The agreement — still basic to government involvement in farm labor procurement - stipulated that the U.S. Department of Agriculture would “avoid disrupting any continuing employment relationships that had been built up between employers and crewleaders.”

Meanwhile, a Western stream of migrants grew rapidly during the supposed labor shortages of World War II. Mexican nationals were imported to work in the fields under the federal “bracero” program. On paper this program required many of the same safeguards as the Wagner-Peyser Act, but in practice it confirmed all the elements of federal farmworker policy in place by 1950: keep the domestic agricultural work force unorganized and deprived of basic labor protections afforded other workers, and undercut any efforts to bargain for better conditions with the threat of importing foreign workers.

The original bracero program ended officially in 1964, but theH-2 program now administered by the Immigration and Naturalization Service still assures growers ready access to low-paid foreign workers on a temporary basis. In the Eastern stream, most of these workers are Jamaican sugar cane cutters and apple pickers. The currently pending Simpson-Mazzoli bill — the so-called Immigration Reform Bill — would expand the H-2 program significantly, posing a serious threat to thousands of domestic workers, especially those trying to follow in the path of the United Farm Workers by organizing themselves into a labor union.

Reform and a Mass Movement

Public outrage triggered by the Thanksgiving, 1960, telecast of Edward R. Morrow’s Harvest of Shame, bolstered by the stirrings of the Civil Rights Movement, led to tentative federal reforms. In 1963, the Farm Labor Contractors Registration Act (FLCRA) required for the first time the registration of all crewleaders. And in 1966, amendments to the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act finally gave farmworkers the protection of federal minimum wage regulations.

The registration act, however, left the grower — the person most able to dictate the terms of the harvest — with no responsibility for the conditions under which farmworkers labored. In 1983, FLCRA was repealed; yet in its 20-year life, the Department of Labor had still not registered the estimated 12,000 crewleaders in the nation. Those who were certified as meeting federal and state labor standards included Tony Booker, who was convicted in 1980 in the first modern slavery case, and Willie Warren, Sr., infamous in farm-labor circles as the “Black Knight.” Warren was convicted of holding workers in involuntary servitude in Florida in August, 1983. He had been referred by the government employment service as a “preferred crewleader” in 1979 and ’80 while he was holding slaves, and again in 1981 and ’82, the year his two sons were convicted of slavery in North Carolina.

The 1960s brought other changes for farm laborers, including coverage under several federal social programs. The Migrant Health Act underwrote construction of a network of public health clinics. A migrant education program targeted funds for children caught in the stream. The Legal Services Corporation began offering legal aid to migrants. And the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) counted migrant and seasonal farmworkers among its clients for job referrals, emergency aid, and basic adult education.

The most impressive gains of the ’60s and ’70s came as the result of a new mass movement among the farmworkers themselves. (See accompanying article on the Florida United Farm Workers’ contract.) It was this movement which instilled confidence and changed conditions for farmworkers, attracted the support of millions of Americans in a boycott of table grapes, forced the media to cover the farmworkers’ story, and pressured the government into creating new programs — however weak — to address the “farm labor problem.”

One thread of this movement among agricultural workers goes back to the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU). In the late 1930s, STFU affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), then in 1946 received a charter from the American Federation of Labor as the National Farm Labor Union (NFLU). During the 1950s, under the direction of H.L. Mitchell, NFLU organized cane workers in Puerto Rico, fruit pickers in Florida, dairy workers in Louisiana, and sharecroppers in Arkansas. In 1960, after merging with the Amalgamated Meat Cutters Union, the NFLU transported over 10,000 Southern black workers to work in canneries on farms in southern New Jersey, in the only known effort by unions to compete with the traditional crewleader system in the stream.

After the merger of the AFL and the CIO in 1956, the NFLU became part of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC). In 1963, the AFL-CIO committed over $500,000 for farm labor organizing, centered mainly in California. Grassroots work by AWOC during the early 1960s in California laid the basis for the emergence of the United Farm Workers Union of America (UFW), under the leadership of Cesar Chavez.

Numerous efforts to organize farmworkers were made in the South, but met with limited success. In 1965, spurred on by the Civil Rights Movement, the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union led a strike of 3,000 cotton pickers which was smashed by the powerful growers. In North Carolina, 1,000 berry pickers began a strike for higher wages with assistance from local poverty agencies. This effort was also beaten back during the summer of 1969 by eastern North Carolina growers. A number of organizing efforts were also attempted in Florida by various unions, including the AFL-CIO’s Industrial Union Department, but none resulted in any lasting contracts or labor organizations.

Farmworker relief and advocacy organizations with church and other support sprang up during these years, paralleling the organizing of workers. As early as 1937, the Workers Defense League launched the National Sharecroppers Fund to raise funds for the STFU. Through the National Sharecroppers Fund and the National Committee on Farm Labor, liberal church and labor supporters helped keep the farmworker issues alive through the 1950s and ’60s.

Support from the Catholic Church and the labor movement for Cesar Chavez certainly escalated the farmworkers’ struggle in California, which led to the first UFW contracts with grape growers in 1966. But inside Congress the farm lobby is still a formidable, well-financed opponent. The absence of a sustained “farmworker initiated” national lobby is not surprising. Farm laborers, the majority of whom are not unionized, are simply too busy trying to meet their basic survival needs to devote the time, energy, and resources necessary to win gains through the legislative process. Advocacy groups can effectively act as a voice for farmworker concerns, but only if they are also promoting efforts by agricultural workers to organize and speak for themselves.

On a state level, the recent antislavery campaign in North Carolina illustrates the potential support groups have for effecting legislative change today, as well as the frustration that results from working through the prescribed political channels. Reacting to 16 federal slavery convictions of migrant labor contractors operating in North Carolina from 1979 to 1982, farmworker supporters lobbied the state legislature to enact an antislavery statute. The proposed bill not only would have made it a felony for an individual to hold workers in involuntary servitude, but also would have made the growers liable for these acts of peonage on their property. The North Carolina Farm Bureau vigorously opposed such a measure, claiming it was an “insult” to farmers because it implied that slavery existed in the state.

After lengthy debate and six drafts of the proposed bill, the antislavery statute passed both houses of the legislature. However, in response to the Farm Bureau’s powerful lobby, the final bill made growers responsible only for reporting known incidences of slavery to the county sheriff. Their crew bosses could be prosecuted, but the growers themselves could still plead ignorance and go free. It was a mixed victory for farmworkers and their supporters: the one-and-a-half-year struggle generated consistent media attention to the agricultural labor conditions in the state and gave state activists a new handle for attacking the migrant labor system; but farmworker supporters say the battle also diverted energy from other concerns and netted only a “token” piece of legislation. As long as the law deflects the responsibility from the growers to the crewleaders, peonage will continue, they argue.

Advocates also came away with a reinforced belief that significant changes will not occur in agriculture until farmworkers themselves come together and demand changes. Farmworker participation in the anti-slavery fight was largely limited to courageous testimony at the public hearings; but judging from the strong impact this testimony had on the press and on legislators, it is all the more imperative that farmworkers themselves initiate organizing activities.

Support groups can also play an important role in the struggle of farmworkers by educating the public, directly and through the media, about the system in which migrant laborers must live and work. Too many Americans view farmworkers not as human beings, but as farm implements: “hands,” or “two-legged animals,” or so many “head” working in the field. Or they are seen only as helpless victims. As their successful organizing attests, farmworkers are people who can “help themselves” and take control of their own lives. Educational efforts through churches, schools, and community groups can confront these prejudices and misconceptions, and at the same time can encourage more local participation in farmworker issues.

An effective method for organizing community support is the consumer boycott. By taking specific actions in the marketplace, consumers can support farmworkers who are already organizing on their own behalf. They can also express their support in an activity which farmworkers have determined is necessary. Currently, the Farm Labor Organizing Committee in Ohio is promoting a national boycott of all Campbell Soup and Campbell-owned products, including its Pepperidge Farm subsidiary; and the United Farm Workers in California are continuing their boycott of Red Coach lettuce. By participating in these efforts, supporters also indirectly pave the way for future activities among farmworkers in other regions.

Finally, there is a strong need for advocacy groups to link up and share information. Workers in the Eastern stream regularly travel between states, yet few organizations coordinate their farmworker-related activities across state lines. Numerous church denominations have set up programs to provide services to migrant workers, but few are in communication with each other. Information on laws, regulations, crewleaders, and local growers needs to be gathered for states in the stream and channeled to farmworker groups and advocacy organizations. Networking of church and social service organizations along the stream is an important step in building a support system for workers who are ready to organize on their own behalf.

Hope for a Union

On Martin Luther King’s birthday in 1983, the Florida sun shone brightly on the United Farm Workers Union (UFW) headquarters in Avon Park, a sharp contrast to the gloom of the early morning Belle Glade slave market, which is 75 miles to the south. Avon Park is home of the only union local of farmworkers on the East Coast and is a beacon of hope for the future.

The UFW members work in the citrus groves of the Minute Maid Corporation, which was bought by the Coca-Cola Company in 1960, the same year Edward R. Murrow aired his moving documentary. Ten years later, yet another television documentary (this time by NBC) focused national attention on the squalid living conditions of Florida’s migrants, and Cesar Chavez’s farmworkers union jumped on the opportunity to negotiate a union contract with boycott- sensitive Coca-Cola. For the 1,500 workers in Coca-Cola’s citrus groves, pay scales finally rose above the minimum wage, crewleaders were replaced by union-controlled hiring halls, and sanitary facilities were provided for the first time in the fields.

After an emotional showing of the King documentary film, From Montgomery to Memphis, our tour group from North Carolina joined with local black and Hispanic workers and their families in “speaking out” about the meaning of the Civil Rights Movement in our own lives. Stories of hard fighting and slow victories followed, and the celebration ended with a roomful of tearful eyes, a circle of linked arms, and a rousing rendition of “We Shall Overcome.”

The UFW celebrants of Martin Luther King Day represent a hard core of true believers in the dream that a union can be built for farmworkers on the East Coast. In spite of indifference from the national labor movement, a lack of resources from the UFW, which had its hands full surviving in California, and federal laws stacked in favor of the growers, the stirrings of small groups of East Coast farmworkers keep the hope of a better day alive.

The Avon Park workers are not alone. Across the state of Florida, grassroots groups of workers have formed self-help organizations with assistance from church agencies and community organizers. In southern New Jersey, migrating workers from Puerto Rico have formed a labor organization called CATA to fight for hiring, wages, and better living conditions. In North Carolina, local black seasonal workers have come together to form county-wide associations to press demands for local hiring of workers, pesticide protections, and sanitation facilities in the fields.

Surrounding these newly organized groups is a migrant stream seething with anger, discontent, and frustration at inhumane treatment. One of the major catalysts for this new agitation has been the entry in massive numbers of Haitian “boat people,” who have become major recruitment targets for migrant crewleaders. Haitians have entered the cutthroat world of the Eastern stream with a deeply held sense of justice and dignity, which has led to field walkouts, legal suits, and continuing mini-protests.

Besides the protests of angry Haitian workers, the Eastern stream has also been shaken by the courageous actions of migrant Southern blacks. For years, the core of the stream has been single black male alcoholics, recruited from the soup kitchens and flop houses of the major metropolitan cities on the East Coast. Surprisingly, members of this traditionally silent group played a key role in the dramatic string of slavery convictions in the last few years. In each of the East Coast slavery cases, older black street people, like Joe Simes of Raleigh, North Carolina, risked their lives to provide eyewitness testimony about the interstate slavery and kidnap operations.

As a melting pot of ethnic and racial groups, the East Coast farmworker stream presents a unique challenge for organizing. For decades, growers have kept wages down and workers on the defensive by playing off different ethnic groups against each other and recruiting new pools of cheap labor, legally or illegally.

To break down these divisions, extensive organizing and indigenous leaders within each of the various ethnic communities of the stream must be developed. Then the question of union organizing returns to the point at which Cesar Chavez found himself in the mid-’60s. There are farmworkers who are ready to put their lives on the line to organize, but no mechanism exists for securing union recognition. Nor are there adequate resources from churches or the labor movement to carry out such a crusade.

Until there is a legislative remedy to the exclusion of farmworkers from the National Labor Relations Act, the prospects for large-scale unionization are bleak indeed. In the meantime, there is plenty to be done to move the struggle forward, as Chavez did for years before winning the first farm labor contract. Political power in East Coast farmworker communities needs to be built and broadened as part of the larger rural black struggle for clout in state legislatures and in Washington. Laws, regulations, and intolerable conditions need to be attacked and changed in issue campaigns that can help build leadership and a greater sense of confidence within rural farm labor communities.

As the famous slogan of the UFW’s California struggle reminds us, “Si se puede. It can be done.” The workers did it in California. Across the South and on up the East Coast, it can also be done.

Tags

L.A. Winokur

L.A. Winokur is the coordinator of North Carolina Action for Farmworkers. Chip Hughes, a former Southern Exposure editor, is on the staff of the Workers Defense League and coordinates the East Coast Farmworker Support Network. (1983)

Chip Hughes

Chip Hughes, a former Southern Exposure editor, is on the staff of the Workers Defense League and coordinates the East Coast Farmworker Support Network. (1983)

Chip Hughes, the special editor for this issue of Southern Exposure is an organizer with the Carolina Brown Lung Association. (1978)

Chip Hughes, a member of the Southern Exposure editorial staff, and Len Stanley have worked extensively on occupational health issues including organizing with victims of brown lung disease in North Carolina. (1976)