This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 6, "Our Food." Find more from that issue here.

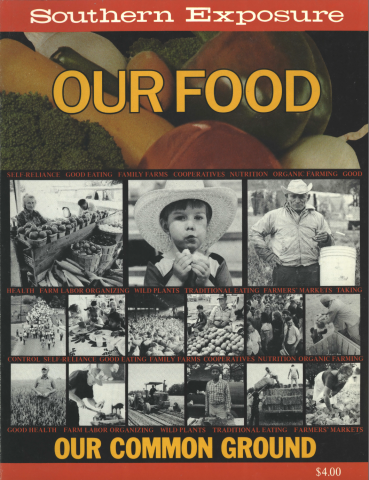

The girl with the cotton candy pictured here is out on the town for a day of fun. She may well eat a nutritious, balanced diet on a normal day; for the moment, though, she is indulging in the ultimate junk food, nothing but sugar and air, a food with no redeeming value. Yet who among us hasn’t stood at a fair or carnival watching the pink sugar being spun into fluff and then walked off munching a puff?

None of us eats a steady diet of cotton candy, so what’s the harm? Not much, probably. But too many of us eat a steady diet that is harmful to our vitality and health; too few of us know or care enough about our nutritional needs to change our eating habits.

Responsible nutritionists have been telling us for years that the typical American diet is killing us, but most of us don’t listen, continuing to eat too many calories, too much refined sugar, too many fats, and too much salt. And most of us rely on over-processed, refined foods, which have lost much of their nutrition and had salt, preservatives, chemicals, and food colorings added in the processing.

The links between nutrition and health — or nutrition and disease, if you prefer — are well-established, although most nutritionists and some doctors don’t think a nutritional approach to health care is awarded its proper place of importance by the medical profession. An Atlanta doctor who bases his practice on nutrition and prevention of disease talked with Southern Exposure — see page 38. And a dietician has offered some pointers on what’s wrong with the typical diet and what to do about improving it — see page 40.

One major reason why so many of us eat improperly is that we’ve never learned differently. In recent years nutrition activists have increasingly turned their attention to what we’re teaching our children about food — and they have been dismayed at what they find. Nutrition Action magazine, for example, recently examined the five best-selling health textbooks and said, “It would be no surprise if schoolchildren thought the most pressing problems posed by inadequate nutrition were beriberi, pellagra, and scurvy, for rarely is heard a discouraging word about high-sugar, -fat, -salt, or low-fiber diets.”

After much research and deliberation, the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs established seven sensible U.S. dietary goals in its 1977 report. All five of the textbooks have been updated since 1980, but only Modern Health, published by Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, mentions the dietary goals, and all five are deficient in major ways. As one editor told Nutrition Action, a consensus must be established before contemporary issues can be included in the text. It seems the consensus must include the processors of highly refined foods and the makers of food additives. Another editor admitted that they studiously avoid information that might be controversial and detrimental to the food business.

No wonder then that children fall so easily into the bad eating patterns of their elders. No one is teaching them that those patterns are wrong. Almost no one, anyway. There are community food activists out there trying to improve the quality of nutrition education. One group that developed a curriculum and a program in Nashville had some success for a time. Its story begins on the next page.