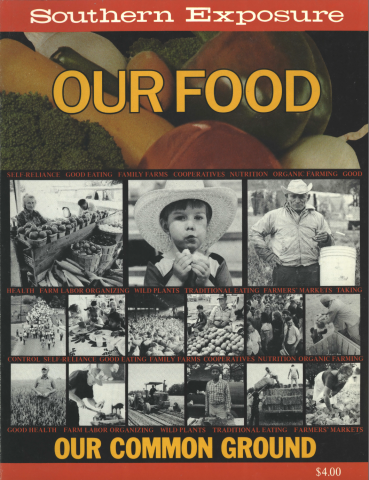

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 6, "Our Food." Find more from that issue here.

Phaye Poliakoff conducted this interview as a part of the radio documentary series “Under All Is the Land, ” which she wrote and produced for WVSP radio in Warrenton, North Carolina, with the help of a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. (See information about the series in the land resources section.) Phaye is now a free-lance writer living in Durham.

Alice Balance vividly remembers her early days on the land when she farmed full-time. “We were happy, we were truly happy” she says, mainly because her family was self-sufficient. It is a way of life that is mostly gone, but one from which a lot can be learned.

At 64, Balance has lived and worked in Windsor, a small town in Bertie County, North Carolina. As a child, she worked on the small farm her father owned. When she married, she and her husband started sharecropping. They raised their children on a farm until 1959, when they were forced off the land to make way for mechanized farming. In the 1960s, during what Balance calls the “protest days, ” she was part of the Free Bertie County Movement. While the group’s original plans called for a supermarket, instead, 10 years later, they opened a rural day care center which serves 16 counties in northeastern North Carolina.

The indefatigable Alice still farms “a little piece” of land, cares for a few hogs and chickens, and directs Kiddie World Child Development Center. She is also president of the Rural Day Care Association of eastern North Carolina, vice chairman of the Bertie County Health Association, a board member of the governor’s Health Advisory Board and the Northeastern North Carolina Tomorrow organization.

Balance’s love of the land, her personal and intimate connection to it, and her realization of its importance form the foundation of her organizing efforts. In addition to working for advancements in rural health care, she is involved in the movement to stop black land loss. People in the eastern part of the state are poor and often powerless, and a takeover by superfarms and agribusiness threatens the region. Alice Balance wants to make sure this doesn’t happen, and to ensure that the people who live there have opportunities to lead full lives. Here she talks about the self-sufficient old days.

Yes indeed, grew up on a farm, fortunately. Out there tilling the soil with our hands, there was close- ness to nature. It felt good knowing all around you was family, it gave a sense of satisfaction. That’s where most spirituals came from, people down working on the farm doing things with their hands. We were really happy in our large families. Each family had its own garden, and we were well fed. We had chickens, milk cows, and fruit - nobody really suffered from malnutrition — and good spiritual and cultural backgrounds.

Oh, in the afternoon we would sing, yes indeed. We would sing and somebody over in the headrow would pick up the song. We worked up to this headrow and would stand and sing and have a good time. As long as we could hear each other, we’d be singing. What did we sing? We came up with “Down Here Lord, Waiting on You.” And my daddy had a poem that he loved to say:

Down on the farm about half

past four

I put on my pants and sneak out

the door.

Out of the yard I run like the

dickens

To milk 10 cows and feed the

chickens.

The people would laugh when Daddy said this. We just had a good time.

When I got married I moved off our family farm. My husband was a tenant farmer so we moved and were sharecropping. In those days you couldn’t tell a sharecropper from a tenant farmer. They had sharecroppers that gave half to the landlord, and they had tenants that rented land from the landlord and worked it like they wanted to. In those times, you could really do your work and nobody would bother you. The landlords usually stayed in town; that’s why you could always raise what you needed to eat. You didn’t make all that much cash money; by the time you paid for your fertilizer and paid back the money that you borrowed to buy flour, sugar, straw hats, and overalls, you wouldn’t have so much cash money left at the end of the year. But you always had your food.

When you were a tenant farmer or a sharecropper, you had plenty of place to grow your food. And you got all the fuel you wanted from the woods. We learned how to raise wheat and make our own flour, and we grew cane to make our own molasses. We could stay at home and grow our own food and be truly happy.

We got up at 5:30 in the morning. The husband went out to feed the team, and the wife would go in the kitchen to fix breakfast. After we finished breakfast, we would hook up the team of mules and go in the fields to work until noon. Then we’d come into the house and fix dinner and eat, and always go back to work at two o’clock. If you were real smart, after you fixed dinner, you could wash some clothes and hang them on the clothesline and be ready to go back in the field at two o’clock. We worked in the field until the sun set, then went home and fixed supper. While fixing supper, I’d heat some water so that everyone could wash up and get ready to go to bed. We’d be so tired we couldn’t sit up for very long; we had to get up early the next morning.

After the growing season there was something called lay-by time, when we’d lay the crops by and didn’t have to work on the farm. By that time the watermelons and the fruits were ripe and we would can - we did a lot of canning and preserving. After that lay-by time passed, it would be harvest time. That’s when we would start picking the cotton and shaking the peanuts and getting ready for winter. Our chief crop was cotton and peanuts. In our county we didn’t grow as much tobacco as they did in other parts of the Carolinas. We raised peanuts, corn, cotton, soybeans, and hogs. We didn’t raise hogs for the market but for our own use. We raised chickens for ourselves, and cows so we could have milk — we always had our own milk and butter. We’d also kill a beef and have that to eat. And we always had our gardens to raise vegetables to have something to give away or sell. Here we were, millionaires, but we thought we were just some poor old country people.

We had to stop farming when the landlord decided he could buy three or four tractors and hire three men to take care of the farm we were living on. There were six families living on this man's farm. He decided he could take all the land and tend the whole farm with three good men, a harvester, a distributor, and a planter. He forced all of us off the farm.

I think often about the six families that tended this man’s land. He didn’t have anything but his self and wife. Why would one man and his wife want everything that was raised on a farm that took care of six families? We had five children, and the other families had an average of five children. There were 42 people living on the farm. The landlord got half of everything we made, but that wasn’t good enough. He wanted it all. So he displaced all these 42 people to take it all. Now he’s so old, and he can’t take it with him.

At first they let us live in the house. But you couldn’t even have a garden; you could live in the house, but you couldn’t farm the land. Maybe you could find a little bit of work on the farm. Afterward, they started moving the houses away, tearing them down, burning them up. We were forced off. We just had to get off and find somewhere else to live.

When the landlord took over, it split up our families and tore our communities apart. We were scattered; some neighbors never got to see each other any more. Some people migrated North and now they want to come back, but they don’t have any place to come to. If you are fortunate enough to buy a lot, it’s so small you can hardly get your septic tank and your pump on it. You don’t have space enough left for a garden or a pig pen.

Leaving the farm really destroyed our life. Had we been able to stay and maintain our family, one of our sons would have stayed right there and farmed. My husband passed and I’m living by myself. If we were still on the farm I would be with my grandchildren and wouldn’t be alone. The family would have always been together and there would always be a home for them to come back to.

All we ever did in our lives was farm. This is something to be proud of. I still believe that the farmers are the ones that feed the nation.

Today there is so much food wasted. ride along and look across the fields. They waste corn, they waste peanuts. They have so many acres, they can't save it all. When we were farming those small farms, we didn't waste anything. If the peanuts shed off, we got out there and picked them up and we sold them. And the corn, we picked it up. What we didn’t pick up, we left for the hogs. Look at the corn across the fields, that’s all wasted. The machines can’t get it all and they mash it underground, or you see ears of corn laying across the field. And cotton, oh my goodness, it’s a shame the way they do cotton. There are machines now picking cotton and all that cotton is wasted. People could be out there working.

It’s a shame to see food wasted when there are people hungry, without food to eat. School kids could go out and pick up this corn on a Saturday, sell it, and use the money for something. That would be a big help and give the kids something to do. But we can’t do it because the land doesn’t belong to us. These big farmers don’t care if it’s wasted. On a small farm, we got out there and made sure everything was picked up and used.

There was a time when people would send kids from the city to go down South and work on a farm. Now, the children in the country don’t have anything to do because the parents don’t have a farm for them to work on. These big landlords have all the land.

I just love the farm, I wouldn’t be anywhere else. I have a son in New York who wants me to come live with him. I wouldn’t live with him, sitting up in some ninth floor, looking out the window to see all the cars go by. I can go across the field down here when I get home and feed the pigs. I have a Perdue chicken house my son-in-law takes care of. He works in a mill down the road and his wife is a telephone operator. I’ve heard so many people say they wish they could come back down South and live on a farm, but they don’t have anywhere to come.

Tags

Phaye Poliakoff

Phaye Poliakoff is a freelance writer living in Durham. Special thanks to Kim Blankenship and Jim O'Reilly for assistance in preparing this article. (1984)