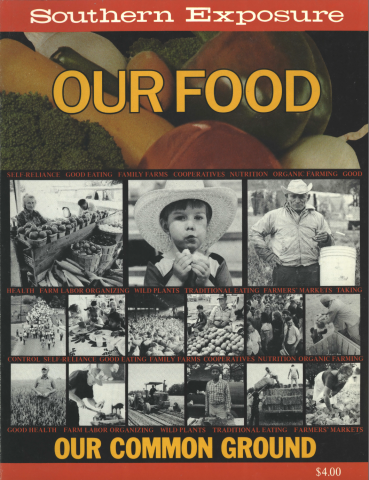

Our Food, Our Common Ground

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 6, "Our Food." Find more from that issue here.

“The food that satisfies hunger,” says an oftquoted passage of Don Quixote, is one of those needs and wants “that equalize the shepherd and the king, the simpleton and the sage.”

Much has changed in the four centuries since these words were written, but food remains our common ground. Unlike the air we breathe, food does not come to us without effort, and it never came to the shepherd in the same quantity and quality as to the king. But Cervantes’s shepherd was less dependent for food on factors beyond his or her control than almost any of us today, and that is not a change for the better.

This issue of Southern Exposure is our contribution toward recovering control over our food — its quality, production, distribution, and variety — and, therefore, toward asserting greater control over our lives in a time that finds our world on the edge of catastrophe. If that sounds apocalyptic, examine for a moment these signs of our crisis:

· The “hunger problem,” never solved but at least assuaged by federal programs like food stamps, has re-emerged as a major issue. The number of hungry people is certainly on the rise. One of the usual indicators is the number of people living at or below official poverty levels; the figure was 34.4 million in 1982, up from 24.7 million in 1977. A recent General Accounting Office (GAO) report quotes an official of the National Council of Churches who works directly with emergency food programs as saying in December, 1982, “The hunger problem nationally is three times — and in some places four times — worse than it was a year ago.”

· The loss of farmland to industrial development, urban sprawl, erosion, and other environmental damage continues unabated. According to the National Agricultural Lands Study, we are losing three million acres every year from a 1967 cropland base of 450 million acres.

· Local variety and choice in food have given way to the pervasive presence of national supermarket chains, restaurant franchises, and corporate brands of over-processed, over-advertised, additive-laden food. Commodity specialization in production means that most of the food grown in the South is shipped elsewhere while most of the food eaten here is grown thousands of miles away. This marketing system deprives consumers of fresh local foods, deprives farmers of local markets, and inflates food prices with the cost of transportation, storage, and countless middleman operations.

· Soaring energy prices also inflate the cost of food through the cost of fuel for running farm machinery and the cost of the petroleum-based agricultural fertilizers and chemicals that U.S. farmers have become dependent on.

· Lower quality and higher prices also result from conglomerate domination of the food industry: only 50 of the nation’s 30,000 food processing companies share 90 percent of the industry’s profits. More than 60 cents of our food dollar goes to corporations that have no direct contact with the farmer or consumer; the figure jumps to 90 cents or more in cases of highly processed foods like canned spaghetti, frozen french fries, or sandwich cookies.

· The capital needed to begin farming — acquisition of land, equipment, and supplies now averages about $500,000 — is largely beyond the reach of the young person who wants to farm. And the increasing inability of existing farmers to earn enough to pay their annual debts means the independent family farmer is a dying species.

· A developing water crisis also threatens to engulf us. In some places, such as parts of Texas, we are running out of water in highly irrigated farming areas. In others, water quality is deteriorating thanks to industrial waste and agricultural chemicals, and healthy drinking water is available only to those who can pay a premium for it.

· Despite increasing awareness of nutrition and growing interest in natural foods, most people’s eating habits remain unbalanced and contribute to the high incidence of diseases that are linked at least in part to diet — from diabetes and high blood pressure to cancer and heart disease.

Such a list could go on and on. The “farm crisis” is fast becoming a national media cliche. We turn on the network news or open Newsweek to poignant stories of family farms on the auction block; the local news runs a week-long series on black land loss; we are again seeing magazine articles and books about people in the U.S. who aren’t just hungry but starving. Yet we still have the paradox of overproduction; we export food; we store or give away huge amounts of surplus commodities; we still subsidize nonproduction; we use food as a foreign policy weapon.

All of these problems are real, but they are not free-standing or unrelated. Hungry, malnourished poor people, bankrupt farmers, and middle-income people doling out ever-larger shares of their income to the supermarket chains are all victims of the same fundamentally diseased agricultural economy. The popular media fail to help us understand that the roots of this crisis lie in the way our system of food production and marketing is dominated by corporate conglomerates.

Likewise, we rarely hear of the many things people are doing, on their own initiative, to help themselves become more self-reliant, to identify and satisfy real needs with local resources, to forge alliances between consumer and producer based on their common needs, to form cooperative enterprises and reduce their dependence on the existing crisis-prone food system. Our Food, Our Common Ground is intended to encourage and support people’s efforts toward more food self-reliance.

In these pages we will meet some people caught up in a net of dependence from which there may seem to be no escape. The South’s biggest agribusiness is the raising and processing of poultry; corporate control of it is all but complete, leaving the farmers who grow the birds and the plant workers who slaughter and process them in a powerless situation which we explore beginning on page 76. But we also explore some of their efforts to escape this powerlessness by banding together in growers’ organizations and in unions. We will also meet the farmworkers of the East Coast migrant stream. If anything their situation is one of even less power, described beginning on page 55. But here, too, there is some hope — and even some success — in farmworkers’ efforts to organize themselves.

Other people we will meet in these pages have taken positive steps toward self-reliance that have met with more immediate success:

· Organic farmers who are freeing themselves of dependence on chemical fertilizers and pesticides to grow healthy food — see page 14.

· A man with a plan to comfortably support a family on a small diversified farm — see page 27.

· A woman who remembers a farm life of near-total self-sufficiency — see page 30.

· Kids who are learning how to eat what’s nutritious and a doctor who says good health is in your power, if you’ll only take charge — see page 34.

· Three groups of people who have applied time-tested principles of economic cooperation to the production or purchase of food — see page 41.

· A community of eighteenth-century Southern Indians who knew how to meet their food needs naturally, without destroying their land — see page 66.

· A woman who can teach you to gather the good things to eat that nature provides in the wild — see page 70.

· A state agriculture commissioner who is trying to take his state’s food economy outside the corporate mainstream, gaining new markets and decent incomes for farmers and providing better food at lower prices for consumers — see page 92.

These people and programs by no means exhaust the supply of ideas and people working for greater self-reliance. But far too much of our food activists’ time and energies are spent these days combatting the first sign of crisis listed in the litany above — the “new” hunger problem — the most damning sign of all in a society of abundance.

The new hunger problem, as many have noted, is one outgrowth of the disastrous social and economic policies adopted by the administration of President Ronald Reagan. As we said, more than 30 million live in poverty. Twelve million are officially unemployed and at least two million more have stopped looking for jobs. Uncounted additional millions more who want full-time work have only part-time work, or can’t support their families with full-time minimum-wage jobs. Through his programs, and transfers of public funds, Reagan has created a whole new population of victims, people not accustomed to dependence on the likes of soup kitchens for a decent meal.

The GAO report mentioned above describes the new profile of the hungry: “No longer are food centers serving only their traditional clientele of the chronically poor, derelicts, alcoholics, and mentally ill persons.... This breed of ‘new poor’ is made up of individuals who were employed and perhaps financially stable just a short time ago. As contrasted with the chronically poor, more of them are members of families, young and able-bodied, and have homes in the suburbs. They now find themselves without work, with unemployment benefits and savings accounts exhausted, and with diminishing hopes of being able to continue to meet their mortgage, automobile, and other payments which they committed themselves to when times were better.”

The economic times may get better again, and this new population of the hungry may get back on their feet. But they will remain people with some first-hand knowledge of hunger and poverty, and that is the one thing we can find to say about this state of affairs that amounts to a ray of hope. We must ensure that this new group of victims joins us in the fight for economic democracy in America.

While it is true that President Reagan has made things worse, he has been working within a system that has never provided enough jobs for all who want to work and has never provided enough food for people on the economic fringe. Food stamps and other programs introduced in the past two decades reduced the suffering, but it is our undemocratic economic system that keeps people hungry. If we want to change that, we must stop simply raging against the powers that be — the corporate farmers, the supermarket chains, the commodities traders, the foreclosing bankers, politics as usual in Washington, and all the rest.

We must also act to take control for ourselves. If we learn anything from the people we meet in Our Food, Our Common Ground, it is that individually and collectively we have a great capacity to create our own set of institutions to produce, market, and purchase our food. The key is decentralized economic cooperation, as Jim Hightower tells us in the interview that begins on page 92. He is speaking of the creation of regional cooperative farmers’ markets, but the idea applies across the board: “giving real economic power to people and making available channels through which they can gain that economic power . . . creating an alternative that’s real.”

He goes on to contrast this approach with the classic liberal one, which would be “to bust up the wholesale markets ... to do something negative to the marketplace. [We say] you need to do something positive to the marketplace. You need to expand it, and give the little people a way around the blockage in the marketplace rather than spending all your time fighting a negative battle.”

This is a lesson taught by the Populists of a century ago. If we can learn from their successes as well as their failures, we may hope to use our experiences of cooperative economic activity as the base for independent, cooperative political activity and for a movement for an economic democracy in which the decisions about who will have how much — food, work, dignity, power — are made by the people. Until enough of us stand on common ground to demand the right to make these decisions, the hungry will always be with us.

Tags

Linda Rocawich

Linda Rocawich, 37, is an editor of Southern Exposure. (1985)

Linda Rocawich, a Southern Exposure editor, lived in Lloyd Doggett’s Texas Senate district for eight years. (1984)