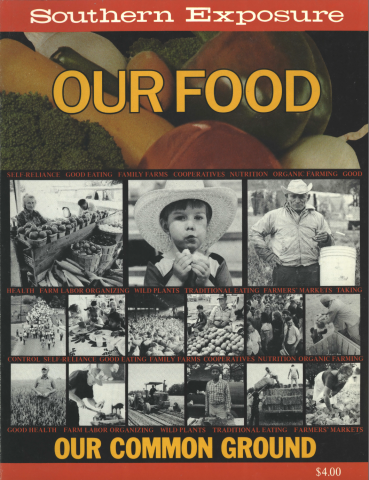

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 6, "Our Food." Find more from that issue here.

The New River Trading Cooperative (NRTC), now housed in a bright, spacious six-room house in Hinton, West Virginia, began like many storefront co-ops as a pre-order food buying club. The 10 people who gathered around a kitchen table in 1974 to assemble a bulk order had found that by pooling their money, they could meet the $200 minimum required to purchase natural foods at wholesale prices.

As representatives of the post- ’60s generation of young people seeking alternatives to a technological society, they also shared common interests in gardening, raising animals, preserving, baking, brewing, and the other homely skills characteristic of rural life but declining or nonexistent in the urban and suburban areas where they grew up. Ironically, a return to the simple life could be an expensive proposition since processed and chemically treated foods are more readily available than natural and organically grown products. Buying food collectively has become one way to beat that paradox.

Summers County, in southeastern West Virginia, is rural but not commercially agricultural because of the mountainous terrain. The population of about 15,000 is spread out on hilltops and in valleys along unpaved roads. During the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s the population declined as work in the coal and railroad industries grew scarce, and people moved to the industrial areas of the East and Midwest. The last 15 years have seen the return of native mountaineers and the arrival of newcomers from cities and suburbs. Most NRTC members are among the latter. Hailing from the East Coast and Midwest, they began coming in the early 1970s to enjoy and learn about the Southern Appalachians and live a rural life. The majority are white and between the ages of 20 and 40.

The organization currently has 25 member households. Larry Levine, a founding member and current treasurer, describes their evolution from food buying club to storefront cooperative. It is a story that is repeated throughout the South as consumer cooperatives attempt to address the day-to-day struggle for survival while learning to make collective decisions, evaluate progress, and determine when and how to make changes.

By the second year of our cooperative effort we were buying too much food each quarter for one home to hold comfortably, so we rented an empty one-room school that we shared with a cooperative free school playgroup. Its sturdy oak floor, wood stove, one-acre yard, and isolated location made it a fine setting for square dances, volleyball games, and costume parties which we held for fun and funds.

We soon developed an order form listing about 60 items and a newsletter to keep in touch with our members, many of whom lived far out in the country. We also began to purchase extra food to sell on pickup day, when members would assemble at the site to sort out more than a ton of food.

In spite of the site’s good features, access for the delivery truck was a continuous problem, and we decided to relocate. We chose the county seat in Hinton, a town of about 4,500. We rented a small room in the middle of the Wizard Waxworks, a local handmade candle workshop right next to the railroad tracks. The central location made it easier for the trucks to make their deliveries and we had enough space to store and package our purchases, even though the environment for repackaging food was not ideal. We maintained a random inventory at this storeback operation and the job of handling all the paperwork fell to one willing co-op member. We continued our quarterly mass pre-ordering, and pushed back the wicks and paraffin to make room for food.

During 1979, we held a number of meetings to discuss the future of the co-op. We wanted to do more than save money on food purchases; we wanted to actually implement cooperative principles in operating our developing business. We wanted all members to be equally involved in the ownership, control, and maintenance of the co-op. This meant that the work had to be more evenly distributed and most members needed to take a more active role in decision-making, which we tried to do by consensus. This process was designed to elicit more commitment, air more opinions, and ultimately bring about a better decision. Consensus can take a long time but it is necessary to a cooperative venture.

After many meetings, we decided to reorganize as a state-chartered, nonprofit, non-stock cooperative, named ourselves the New River Trading Cooperative, Ltd., and received a charter to “provide nutritional, cooperative, and social opportunities and to promote cooperative alternatives.” We also decided to open a store in Hinton that would be open to the public. Then we had to get by a local USDA official who had been resistant to NRTC’s accepting food stamps. There have been changes in food stamp regulations since then that make it easier for food buying clubs to get authorization. But we had to suffer through more than 40 exchanges of correspondence with state, regional, and national officials in West Virginia, Philadelphia, and Washington before we got the go-ahead.

The decision to go public was a big step for us. We had to invest more of our resources of time, work, and capital, which were all limited. We also had to give up some of our privacy. But we had decided that the advantages outweighed the disadvantages. With a central location we gained convenient access, more space and product variety, greater community interaction, and expanded opportunities for information and social exchange among members. Many of our members still live far back in the hills without phones or cars, so sharing a base in town was a welcome addition.

NRTC opened for business on September 1, 1979, in a small low-rent building in an alley just a block from downtown. Operating three or four part-days per week, the co-op expanded its membership and made some sales to the public, nearly doubling its gross sales in a year. A low-ceilinged room about 16 feet square served as the store. Two extra back rooms were used for packing and storage. With most of the floor space devoted to bulk bins and buckets, more than three people constituted a crowd. Natural light was scarce and there wasn’t enough space for children or for the social interaction that we all considered important. But we survived these difficulties and in the process members learned how to run a store.

At the beginning of our fourth year, we took a survey of the membership and decided to move again. Two of our members purchased property nearby and we leased from them the ground floor of a high-ceilinged, turn-of-the-century house. At the new location, we’ve been able to expand our activities and services to the membership and the larger community. We’ve placed a large, categorized bulletin board in the entrance hall where customers can survey announcements, schedules, recipes, and other information.

There’s now ample space for activities beyond the actual food market, including a large room for children stocked with toys, supplies, a crib, and a free clothing exchange. The kitchen is a regular gathering place for sharing tea and talk and holding cooking classes and committee meetings. The backyard picnic table is equally popular in good weather. The center is large enough to share with a county home-schooling group and a birth preparedness instructor. These activities all reflect the interests and philosophy of the membership and encourage community participation by allowing us to offer ongoing educational services.

Our location on Hinton’s main street helps promote public exposure and sales. Annual sales for 1982 reached $13,500. We estimate that sales at our new location will increase by at least 10 percent. There are four or five other small markets in town, one independent supermarket, and one chain supermarket. But many of the products we offer are not generally found there and our prices on such common items as grains and beans compare favorably with those of all the stores.

The store operates on a 20-hour week and stocks more than 250 items. We buy and sell most foods in bulk so the purchaser can choose any quantity desired, but we pre-package items like liquids, spreads, and cheeses in our fully equipped late-’50s style kitchen. We stock primarily natural, whole foods, organically grown when available at reasonable cost. We have also offered garden and beekeeping supplies, plants, books, and other items. We avoid perishable produce because gardening is so popular, and there is a tailgate farmers’ market nearby that we don’t want to compete with.

Posted prices are 40 percent above cost except for items produced by members, which the co-op encourages by adding only a 10 percent markup. We also support other cooperatively owned and collectively operated businesses by setting lower prices for their products. For example, the members of the co-op agreed to allow a price differential support program favoring Mountain Warehouse, the cooperative distributor operated by the Appalantic co-op federation. And a vast selection of herbs, teas, spices, toiletries, and related items are shipped in from Frontier Cooperative Herbs in Iowa.

We encourage members to work in the co-op by offering a 16 percent discount. To get it, each household must clerk two hours per month per adult in the household. A clerk’s duties include stocking, packaging, checkout, cleaning, and whatever else comes up since, once trained, only one person works at a time. An 8 percent discount is allowed at the checkout counter to senior citizens, travelers who belong to other co-ops, members who have missed work, and people who’ve been designated as “friends” of the co-op.

Natural foods marketing has grown over the past 20 years from a network of small stores into a big business that is attracting the interest of supermarket chains. Even the convenience and discount chains like 7-Eleven and K-Mart are experimenting with the profit possibilities of natural food merchandising. Paralleling this is the phenomenal growth of co-ops themselves. The Co-op Directory grew from 2,500 to 10,000 listings in a single year, and in 1980 national co-op membership was estimated at 3.5 million people. Co-ops have reached out from urban student centers to small cities, from town to country dwellers, and now there are federations, warehouses, and natural product lines. A small co-op like ours does not have the financial resources of these newcomers. But if we focus on our strengths and continually seek to resolve difficulties, we can hope to take what we can use from this boom and our members can continue to realize satisfaction and enrichment through participation in the New River Trading Co-op.