Co-Ops

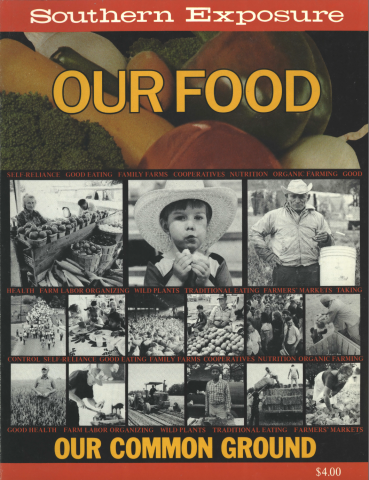

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 6, "Our Food." Find more from that issue here.

Community cooperation is not an idea that is new to the South. Traditionally, rural societies have always banded together to get work done. Some of the more common cooperative practices have centered around the production and distribution of food. The repair and maintenance of outbuildings, barnraising, slaughtering and dressing animals, canning, harvesting, and gardening are all examples of shared tasks that earned those who participated either a share of the produce or reciprocal labor.

While the change to a cash economy has diminished these practices, it has not eliminated them. Many people with families living in rural areas still share in the upkeep and maintenance of commonly owned property. Those who are not available to provide labor may contribute cash, entitling them to share in the garden produce, fruits and nuts, meats, and even profits from the cash crops. Urbanization and industrialization have isolated many people, and the idea that personal benefits may be gained by sharing work and resources with other people is not as widely shared as in the past. Yet, the tradition is a strong one, and cooperation is a viable alternative to the wasteful, expensive marketing systems which now control our access to food.

In the South today more and more people are again turning toward cooperative ventures, for both economic and political reasons. These co-ops draw upon many of the same philosophies by which communities have worked together in the past, except that now they are more frequently formally structured, with responsibilities more specifically delineated.

There are two basic types of cooperatives, producer and consumer, and both represent a wide range of interests. Historically, however, producer co-ops have been primarily agricultural. With the cost of farm machinery so high, and the market for selling the crops competitive, it made economic sense for farmers to collaborate and share in the purchasing, production, and marketing.

Consumer co-ops have traditionally been food cooperatives. Individuals wanting choices of food that is both nutritious and inexpensive band together into food buying clubs and storefront co-ops. Membership in a food cooperative also enables consumers to exercise choice about where their food comes from and thus react to the advertising myths fed to shoppers by supermarket consumerism.

The politics of both types of cooperatives vary from co-op to co-op. However, by coming together and working cooperatively, individuals have already made a basic “political” decision. The cooperative alternative illustrates an attempt to address the issues centering on the corporate control of food production and distribution, and to restore a sense of self-reliance and respect for the land to community members.

The potential for education and change through cooperative endeavors is great. Because each member of a cooperative must assume some responsibility in the functioning of the co-op, members are frequently participating in differing degrees of decison-making which will determine the extent to which the co-op will be politically defined. For example, in the case of producer cooperatives, questions will arise concerning how to market the products and to whom they will be sold. Will the best price offered be the criterion on which to base this decision, or will a specific market be targeted, and if so, for what reasons? Similarly, members of food cooperatives must make decisions concerning food policy. Where does the food come from? Is it locally grown? What about carrying pre-packaged processed products from large corporations? In what kinds of activities are these conglomerates involved both here and abroad and would the co-op support these? Will the co-op promote the efforts of organized workers and boycott products? What about food that is sprayed with pesticides and other chemicals? How will “nutritious” be defined, and by whom?

The philosophical stance of a co-op is reflective of the membership. Commonality of interest among members of a homogeneous group is conducive to cohesiveness and basic agreement on the co-op’s orientation, both of which add to the longevity and stability of the co-op. However, such homogeneity may also breed a kind of exclusivity that limits access. A more diversified membership, on the other hand, may have a more difficult time trying to arrive at any kind of political position, yet because of this variety among the membership, such a co-op does not seem to be in danger of insulating itself as narrowly.

Each of the three cooperatives profiled in the following pages has a different story to tell. The Hilton Head Island Fishing Cooperative, on the South Carolina coast, is a producer co-op originally formed for economic purposes. The New River Trading Company in Hinton, West Virginia, is typical of food cooperatives organized by individuals seeking alternatives to corporate control over food choices. The Acadian Delight Bakery and Grocery in Lake Charles, Louisiana, under the umbrella of the Southern Consumers Cooperative, formed their producer co-op as a community development effort, and it has served as a springboard to involvement in a variety of community-oriented projects. □