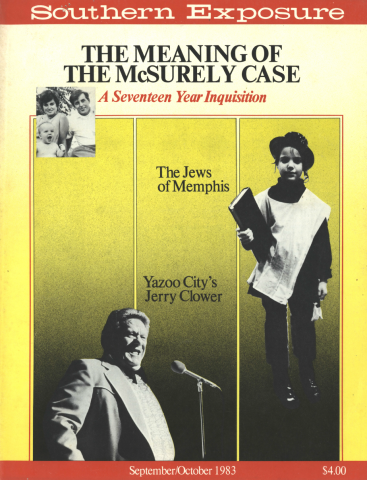

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 5, "The Meaning of the McSurely Case: A Seventeen Year Inquisition." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Green AstroTurf covers a makeshift stage erected at the far end of the high school gym in Dunn, North Carolina. A basket of gladiolas sits before a microphone stand. Tonight's door prizes have been awarded — a black and white TV, a bun warmer and server, a food processor, a tea kettle, and a basketball. A banner hangs on the institutional green wall behind the platform: "Welcome Stockholders: Agriculture Deserves the Credit."

It is the annual stockholders' meeting of the local Production Credit Association, a farmers' credit union, and the bleachers are packed. Folding chairs accommodate the rest of the 2,000 farmers and their families here tonight. The lights are up, and six-foot-high speakers, usually reserved for school assemblies, are in place on either side of the stage. But most of this assemblage did not come for a recitation of dividend and figures. They came to hear Jerry Clower — "America's Number One Country Comic," a 270-pound man stuffed into a yellow polyester tuxedo with a raccoon emblem on the jacket and lapels so wide you could land a Lockheed Tri-Star on them.

He bounds from stage left onto the gym floor. He stops just short of the audience, arms outstretched like a defiant gladiator, gives a loud rebel yell that owes more to Johnny Weismuller than to Stonewall Jackson, then darts over to two middle-aged women in the front row, kisses both, unleashes the rebel yell again, and runs up on stage.

"Whoooooooooo!" he bellows over the mike. "Shooooot this thang!!!"

Before the laughter and whistles can subside, he steps back, licks his lips, grips the microphone firmly with his large hands, then leans into it: "I don't know of any place I had rather be than. . . ." He pauses before stretching out the local hook to his stock encomium: "Duuuuuuuuun, North Carolina!" Another Rebel yell, and his fluid Mississippi baritone brings it all the way home: "I'm on yore side," he tells them. "You know, to throw me in amongst a bunch of people who promote P.C.A. is like throwin a rabbit into a briar patch."

Clower's white mane, which he pauses again to comb for the same reason that Bob Hope stops to swing a golf club, evokes Andrew Jackson. His craggy visage suggests a cross between Arthur Godfrey and Buddy Hackett, his high-powered delivery, Andy Griffith's country music demagogue in A Face in the Crowd. In short, Clower looks, talks, and acts like what he is: a former sharecropper and fertilizer salesman turned comic and Baptist lay preacher.

Minnie Pearl, Steck Rose, String Ban, the Duke of Paducah. To anyone who grew up with the Grand Ole Opry, these names form a sort of pantheon of country comics. Before the South became the Sunbelt, before country music became the Nashville Sound, the country comic was a mainstay of any country music show. Coming on before the main act, with garish clothes and downhome manner, the comic regaled audiences with one-liners and stories drawn from country life. He (or she) became to the white rural Southerner exactly what the Lower East Side schtick comics of New York City became for the Jews of America — the voice of an authentic ethnic humor.

But as country music in recent years has largely waxed in national acceptance, country comedy has waned; its only national outlet is the Nashville-produced TV program Hee-Haw. The Jerry Clowers, Justin Wilsons, and Cotton Ivys make a living, but mostly in a regional market — off record and tape sales, banquet appearances, and Nashville-produced syndicated TV.

Jerry Clower enjoys in the Deep South a folk celebrity roughly comparable to that of Alabama's Coach Bear Bryant, yet his name remains largely unknown above the Mason-Dixon Line. National acclaim eludes Clower, and he can be defensive on the subject of his regionalism, as when he recalled a 1971 encounter with a talent coordinator for NBC's Tonight Show. "They said I come on too strong for Johnny."

For Speck Rose, whose blacked-out tooth, green-checkered jacket, and bowler are mainstays of the Porter Waggoner show, the only question is, whose regionalism? He recalls forays he and other Southern-based comics made into the North. "They just didn't understand our type of comedy. The other comics who work out of L.A., New York, Chicago, they're telling jokes out of what they see every day — the cities, the traffic, the subways. Johnny Carson can pop one on you, and everybody laughs and goes on. Well, you put him in the rural areas of Alabama, Georgia, Arkansas — they will appreciate and enjoy the joke, but they won't relate to it like they would mine or Jerry's."

But if country comedy furnishes the context of Clower's show business aspirations, his comedic idiom draws on far deeper roots, into the South of the nineteenth century. During the 1840s and '50s, there emerged in what was then called the Old Southwest a literary humor that in its bravado, vulgarity, and iconoclasm was far removed from the mannered literature then being produced by New Englanders like Oliver Wendell Holmes, William Cullen Bryant, and John Greenleaf Whittier.

The humorists of the Old Southwest sought to recapture the voice and life of their disappearing frontier. In their recounting of bare-knuckled fights, coon hunts, and whiskey-sodden outbacks, their works, which would later influence Mark Twain and William Faulkner, celebrated a boisterous regionalism in the face of the growing homogeneity of Jacksonian America. In their tall tales — sometimes ribald, always class-conscious and anti-urban — writers such as Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, Davy Crockett, and William C. Hall sought to preserve for posterity a unique time and place.

Clower's own literary sources extend no further than the Jackson Daily News and the Yazoo Herald, but his comedy draws on the same tap root. "I've had people come up to me and say how much they appreciate me making those records, so people'll know how we lived back in them days during the Depression," said Clower. "I bring up some words like the furnish merchant, the country store, rat killins, candy pullins, peanut boilins. Well, that was the culture of the world, Son! I mean a peanut boilin in them days was right up there with the sorority dance or the Junior League Valentine Day dance."

"Even as a kid [in Liberty, Mississippi], I had to outdo everybody at the swimmin hole. I had to dive off the highest limb, where at the school the next Monday, they'd say, 'You know, Jerry dived higher outta that tree than ole Lane Newman.' 'Oh, he did, did he?' 'Yeah, he took a runnin start and dove off that bridge — he's gonna kill hisself!'"

Clower's extroversion is hardly that of the classic comic type who becomes outgoing to overcome a brooding introspection. ("Hell no, he ain't changed," one local told me, "he's always been a damned loud-mouth.") The worst aspect of selling fertilizer, Clower remembers, was being alone on the road. As a travelling comic, he tries to avoid lay-overs for the same reason. "If I get a day off, and it's not feasible to come home and there's not any movies or sports on TV, I have to get out of there and go to hustlin up somebody to talk to — if it ain't nothing but some waiters in the hotel restaurant — cause I just don't like to be alone."

It was at a 1971 public relations outing in Lubbock, Texas, that a local disc jockey taped a Clower monologue, gave it some airplay, and, later, promoted a locally produced album. "From then on," said Clower, "after every talk I gave, I'd say, 'You send five dollars to Box 2122, Lubbock, Texas, and you can get my album.'"

Within a year the record sold 8,000 copies, enough to draw the attention of MCA Records, which offered the fertilizer salesman a contract. "It kinda scared me, cause I didn't know what was happening," Clower remembered. "Owen Cooper, president of Mississippi Chemical, called me into his office and said, 'Now, Jerry, what's happening to you could be tremendous, or it could just blow over, but we are willing to share you for a while — until you find out which way you're going.'

"Now, if he had forced me to make a decision, I would have stayed with fertilizer. I would have said, 'Bye-bye, show biz.' See, I was 44 years old and I had a family. That's old to be backin into show bidniz."

After Clower signed with Nashville agent Tandy Rice, MCA re-released his first album, Yazoo City Mississippi Talkin'. Soon thereafter a single from the album grabbed the attention of country music disc jockeys across the South. "A Coon Huntin' Story," a boisterous Clower recounting of a night-time hunt in his beloved Liberty, Mississippi, sold 150,000 and made the fertilizer salesman's name a coon celebre among old boys of the region. "The bottom line," said Clower, "was November, 1973, when I was inducted into the world-famous Grand Ole Opry."

Clower's career often seems like some pecuniary incarnation of the Hindu god Shiva, with each of his many hands washing the others. In exchange for promotional appearances, Clower still draws a salary from Mississippi Chemical — "enough to keep my Blue Cross paid up." He often peppers his stage and banquet talks with plugs for products he has endorsed — autos, coffees, pesticides, chain saws. During a recent pep talk to a radio broadcasters' convention in Nashville, Clower launched into a sermon on the virtues of enterprise and loyalty, invoking Delta Air Lines as an organization embodying those values. Clower tapes are standard fare on many Delta routes.

Clower brings to his dealings with the press the same hard-sell that he brought to his fertilizer sales route, and he plays out the country-boy-made-good role to its ultimate: "Why, I sell more records before breakfast than some of them big dogs in Hollywood sell all day." A recent Clower junket included trips to his mother's house in Liberty, Mississippi, to the nearby baptismal hole, and to "that old shack what I growed up in as a sharecropper" —where Clower genially posed in the front yard by his Cadillac. Later, there was a stop at brother Sonny's house in McComb, Mississippi. Finding Sonny out, Clower decreed that the photo opportunity should not be wasted. He posed instead with Sonny's prized bulldog. "He's always on," said Larry Mimms, a Nashville adman. "He sprays his personality everywhere he goes. Nobody knows quite where it comes from, but he's always on."

Not always. Clower can be judiciously silent when he needs to be: "I didn't go to Dade County when Anita Bryant asked me to come. I told her I didn't have a dog in that fight. And she said, 'Jerry, all Christians have a dog in this fight.' I said, 'I do not. I'm perfectly willing for the people of Dade County to settle this issue with no outside interference.'

"And my reason for that was, I remember during racial strife in the state of Mississippi I was doing my best to be Christian and to follow my Christian convictions in all of my actions in this situation. And right in the middle of cooler heads tryin to prevail, and tellin folks what the law is — up drove a busload from Boston, Massachusetts, with Mrs. Endicott Peabody callin us bigots, gettin off that bus with them placards.

"Well, they came within an inch of causin me to forget all of the progress I had made in the last few years."

"That Yazoo, " said Mike, "is the dundest hole that ever came along. . . . Talk about Texas. It ain't nothing to them Yazoo hills. The etarnalest out-of-the-way place for bar, an' panters, an' wolfs, an' possums, an' coons, an' skeeters, an' nats, an' hoss flies, an' cheegers, an' lizzards, an' frogs, an' mean fellers, an' drinkin, an' swapping bosses, an' playin ' hell generally, that ever you did see! Pledge you my word, 'nuff to sink it."

— William C. Hall, "How Sally Hooter Got Snake Bit" April 13, 1850, Spirit of the Times

One hundred and eighty miles south of Memphis, 40 miles due east of the Mississippi River, Yazoo City, pop. 12,000, whose Yellow Pages offer 48 churches, straddles the rich delta of that river and the first range of hills to the east of it. Coming to Yazoo from the river, U.S. 49 passes through the Delta's fecund cotton fields and comes finally to the downtown district, with its two-story storefronts, most built soon after the 1904 fire that leveled the town.

Southwest of the business district, astride the tracks of the Illinois Central, lie the gray and splintered shotgun houses where Yazoo's black citizens live. These structures cluster along dark corridors whose appellations — Swamp Street, Locust Street, Water Street — pay tribute to the muddy Yazoo River that snakes behind them to the southwest on its way to join the big Mississippi above Vicksburg.

East of downtown Yazoo, Grand Avenue offers a South found in other old port towns of the region — insular and pedigreed communities with names like Natchez, Savannah, Charleston, and New Orleans. Their claim to prosperity is not that of the manufacturing South of Birmingham or the commercial South of Atlanta. No, the Victorian homes, two-storied and lattice-adorned, that line Grand Avenue, and its ample lawns of gingko, dogwood, and pecan trees, evoke an older and — its residents would add — more mannered wealth.

Still farther east, away from the rivers and their lowlands, beyond the opulence of Grand Avenue, lies the hill country of Yazoo, with its hardwood forests, its isolation, and its scrappy sons who drive Dodge pickups with gun racks and National Rifle Association bumper stickers along its lonesome backroads.

While Clower now lives comfortably with his wife and two of his children on Yazoo's delta, he quickly adds in interviews that he is of those hills, that he and his people came from this same range of uplands — only 150 miles to the south. "Route 4, Liberty, Mississippi," to be precise, a backwoods community six miles north of the Louisiana state line.

"My daddy was a sawmill hand. And so we got out and moved in with my grandpa, and started sharecroppin. So, I did grow up choppin cotton and plowin mules and playin gator at the swimmin hole and settin at the country store. . . ."

The lowland-highland tension at the core of Yazoo City's identity animates much of the ambivalence, if not outright resentment, of some townspeople on the subject of Jerry Clower. "I wouldn't call it resentment," said Linda Crawford, director of the Yazoo Triangle Arts center. "I think there's kind of a love-hate relationship in this town with Jerry. We're glad he's here, but we like people to know that there's a lot more to Yazoo City than Jerry Clower. You know, [novelist] Willie Morris is from here too."

Another local put it more bluntly: "Willie Morris is more Yazoo City than Jerry," he said. "Jerry's of the hill country. He's really more Route 4, Liberty, Mississippi. You see, Willie's father worked at a gas station but his mother taught music on Grand Avenue, visiting those Victorian houses wearing her white gloves and leaving a calling card when she came by.

"Route 4, Liberty, Mississippi, is that mosquito-ridden hill country of rednecks and sandy soil and red clay and pine trees. So you see, Jerry's not really Yazoo City."

"It's real simple," offered Clower, straightening out the confusion. "I was birthed at Route 4, Liberty, Mississippi, and grew up there. And most of the tales I tell happened there, with the Ledbetters, while I was coon huntin and fishin and huntin rabbit and playin gator at the swimmin hole. Then, in 1954, when I got out of Mississippi State University, I found work at Yazoo City. And I been here ever since."

It was this milieu of highland life that Clower drew on to create the Ledbetters, the family who garrulously inhabits his Route 4 tales. By now, Uncle Versis Ledbetter, his wife (Aunt Pet), and the rest of the highland clan (Ardel, Bernel, W.L., Lanel, Odel, Marcel, Newgene, Claude, and Clovis) occupy an almost mythic realm in the state of Mississippi. During a recent appearance, Clower drew laughs when he spotted a local south Mississippi congressman and introduced him to the audience as "Marcel Ledbetter's congressman."

For Clower fans, speculating on the true identity of Marcel Ledbetter is something like a parlor game, and Clower is not about to discourage it. "I won't specifically point out who Marcel Ledbetter is. He could be one of two or three people. And I'm glad I never did identify him. CBS'd be wantin to go down there and do a documentary on him, and Marcel would wind up killin Walter Cronkite. That'd be awful. They don't like cameras. They think TV cameras has caused all the troubles in the world."

When one considers the demographics of the state Marcel Ledbetter calls home — Mississippi is 37 percent black — blacks become a conspicuous absence in Clower's tales. The omission is deliberate: "If we had grown up enough, I could get by with mocking blacks. I could do some black dialect. I could tell some real black stories that happened. Some of the stories I tell, some of the folks is black, but it's not necessary to identify them. Ain't nobody's business. They's friends of mine. We's all in the swimmin hole together.

"I have people come up to me an say, 'Boy, that sho is funny bout that wildcat eatin that nigger in that tree.' I say, 'I don't believe you heard that on my record!' "Fellow'll say, 'Yeah, you know — that John Eubanks, who climbed up there to get that raccoon.'

"I say, 'Man, John's my first cousin !' Well — here's a fellow who's an obvious bigot, and it was funnier to him if that bobcat was jumpin on a black fella. But John Eubanks is a man — an he be black or white, it don't matter. He climbed the tree and he said, 'Just shoot up here amongst us, one of us got to have some relief.'"

During the racial turmoil of the 1970s, Clower gained a reputation as a racial progressive in Yazoo City. During the past two presidential campaigns, he supported former president Jimmy Carter, an advocacy that in 1980 won him the enmity of the local Moral Majority — at the mention of which Clower bristles. "I disagree with pittin one group against another. Some super-Christians bother me. I feel like some of 'em are so heavenly-minded, they ain't no earthly good."

But it is on the subject of the Moral Majority's advocacy of private education that Clower, a tithing Southern Baptist who speaks often in white and black churches, firmly parts company with many of his fundamentalist brethren. "I was raised and grew up as a bigot. And I don't particularly criticize my folks, but as I got older, my Christian convictions got to prickin my conscience — and I couldn't continue to believe some of the things I believed and did, and claim to be a Christian. And I changed.

"I have some Christian convictions, and I try to practice what I preach. And I fought a war to give a man the right to be a bigot. You can be a bigot in America if you wanna be — but I want you to admit it when you are one. I don't want you to say and teach your children that you ain't a bigot when you are one. I mean, if you got a school, and you don't want blacks in it — put up a sign. It ain't no problem, it ain't no complicated thing. Just put up a big old sign out there — 'For Whites Only' — and let's get on with it."

When I was a boy, if you was reached the age of accountability, you could have the freedom to go wherever you wanted to go," Clower tells his audience, finding his way into a story requested before the show's start.

"But the minute you diiiiied — they assigned at least four people to watch you. I mean, if you died, they didn't think of leaving you by yourself. Clower picks up the pace: "So I went to a funeral not too long ago. It was ten o'clock at night, and a great big fella got up with a three-piece suit on and says" — Clower parodies the dulcet baritone of an institutional voice: "Ladies and gentlemen, this funeral home closes at ten o'clock. We'll open back up at nine o'clock in the morning.'

"I looked over at my mama and said, 'Hallelujah, they done figured this out. Let them old undertakers set up with the dead!'

"Well, everybody got up to leave, and Uncle Versie said, 'Sir, this is your funeral home, and you can run it any way you want to — but I'd just feel a little better if my boys, Newgene and Clovis, set up all night with my friend here. Now y'all just go ahead and shut the door and just leave 'em in here.'

"Well, everybody left, and there's old Newgene and Clovis settin up in there, smellin them flowers. . . . Well, after about an hour, Newgene could see a beer joint — with that light flashin on and off."

Clower savors the scene. Pantomiming, he holds out his arms and rocks his massive frame on the soles of his white cowboy boots, suggesting the metronomic regularity of a blinking sign.

"Newgene says, 'You know, I believe I'll just step over yonder and get us somethin to drink.'

"Clovis says, 'No, I ain't gonna stay here with him by myself — I'll tell you what, Newgene, since you brought it up, you stay here with him and I'll go and get us somethin to drink.'

"Newgene says, 'Huh-uh, I ain't stayin here with him by myself, either.'

"So they stay there another hour, and they got to wantin somethin to drink sooooo bad. . . . Mouth getting dryyyy!" Clower rolls his tongue around like a man in a desert facing a mirage, then gives his rebel yell and telegraphs the next line: "So they decided they'd go get somethin to drink and just take the dead fella with 'em." The audience roars as Clower builds the story like a slow-working carpenter.

"So they got him up — one on one side, one on the other. And here they went. Dead fella was in the middle. . . . And every once in a while they'd bounce him, so it'd look like the dead fella was takin steps."

Clower pantomimes the dead body moving toward the beer joint, his posture and facial expression freezing into a corpse-like rigidity. Throughout the act, Clower gesticulates with the animation if not the grace of a veteran traffic cop — his Liberty Bell physique underscoring the humor of his movements.

"They walked right into the beer joint — walked right up to the counter an stood the dead fella up. . . . Eased a three-legged stool round on his back, where he'd be wedged in there good. Newgene was standing on one side, Clovis was on the other — drinkin!

"The dead man was the best dressed man in the whole beer joint!

"About that time a fight broke out!" Clower screams as if bearing witness to bestial violence. "Fist City!!!!" he shouts, rocking into a flurry of onstage shadow-boxing and kicking, giving a blow-by-blow account of the redneck contretemps: "Here they went! Bustin chairs over one another's heads!"

Clower plays out the fight. "Wop! Bop! Woooooo! — Down they went! A fella drawed back in the melee and hit the dead fella up-side the head and just cut him a flip — down in the middle of the floor the dead man went!

"Waaaaaaaaaaa!" Clower screams. "Here comes the sheriff — blowin them sireeens, linin them up against the wall, searchin them. . . . 'Ahhhhh!' And Clovis Ledbetter fell down by the dead man, and put his arm under his head. 'Ahhhhh,' said Clovis, 'Ahhhhh! Speak to me, speak to me. . . .' Then he looked up at the fella that hit him and said, 'You! You killed him!'

"And the sheriff went over there to handcuff the man what hit him, and the fella said, 'Wait a minute, sheriff. Hold onnnnn!

"I ain't gonna lie about it — I was in the fight. I did hit that fella — but it was in self-defense. He pulled a pocket knife on me!'"

As the applause, whistles, and laughter well up, Clower punctuates his punch line with another rebel yell, licks his lips, wipes his brow, giggles, and tucks his enormous belly in. Returning his handkerchief to his coat pocket, he gives a high, mischievous laugh, steps to the microphone, and states the obvious:

"I am a country fella. I feel like I am one of you. Because I did grow up on a farm. I do have a degree in agriculture. I am country. I ain't ashamed of it. . . ."

The digression leads Clower into another story, another digression. Then, forty-five minutes after starting, the comic approaches the coda with which he closes.

"I am convinced," he says, taking an oratorical tone, "that there is just one place where there ain't no laughter. And that is hell. And I have made arrangements to miss hell. So: ha, ha, ha!" It is pure Clower, and the audience loves it.

"So I ain't never gonna have to be nowhere where some folks ain't laughin! And if you know of anybody that don't believe in laughin, and they walkin around with a hump in their back and their lips pooched out — they ain't gonna laugh at nothin! You tell them to go home and look in the mirror and see what all us other folks been laughin at all these many years! Thank you!"

Clower's gray-green eyes betray his fatigue. Sweat stains his world-famous raccoon tuxedo. He greets the audience's standing ovation wide-eyed, arms raised, mouth wide open, a worn but still jovial clown.

Tags

Tom Chaffin

J. Thomas Chaffin, Jr., writes on North American politics and culture for The Nation, The Progressive, and other journals. A native of Atlanta, he recently completed an M.A. in American Studies from New York University. He now lives in San Francisco. (1983)