Ruth in the Silver River

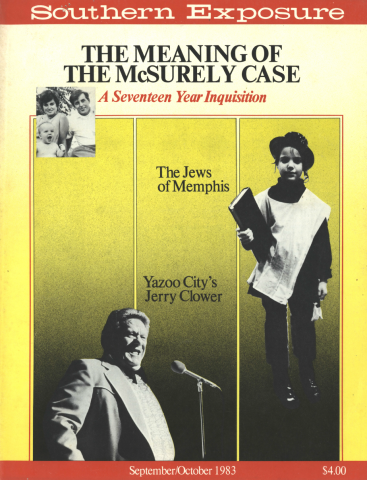

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 5, "The Meaning of the McSurely Case: A Seventeen Year Inquisition." Find more from that issue here.

On a morning near the end of October, the preacher's household awoke to a rain of small white globes the size of birds' eyes. The hail purred as it pelted the earth and vanished in its own sound before the children could stroke it. "Spider eggs," William told his sister Caroline. "Flowers," she said. "Ice," their mother explained, and called them indoors. For Ruth Wilkinson, the preacher's wife, the hailstones were yet another sign of a crack in the natural order, a foul-up people seemed to be shutting their eyes to. Her geraniums had not bloomed for a month; grass wilted and sandspurs sprung up in its place; mockingbirds rattled out the songs of crows; the cedars moaned when there was no wind; and when there was wind, between its breaths the crash of the surf 40 miles away could be heard. And always there was a prickle of salt in the air, as if the land were creeping, dragging itself back to the ocean.

"Come in," Ruth called again to the children. They ran into the kitchen, shaking invisible pellets from their hair.

"Now, quietly, quietly," she mimed, posing her pointing finger before her lips, "tiptoe into the bathroom and wash up for breakfast."

"In stadiums across Japan and Australia," she recalled her husband's exhortation yesterday, "he is witnessing to millions. To millions! It is not enough to say 'JACKSONVILLE FOR JESUS,' 'POMONA PARK FOR JESUS,' or even, 'FLORIDA FOR JESUS.' We must say over and over, as our great evangelist has often shouted, 'THE WORLD FOR JESUS AND JESUS FOR THE WORLD!"'

Her husband dwelled in a house of possibility but found himself confounded by trifles like cracked distributor caps, too little money, and sleep. So on the day after Sunday he would twist in bed and grumble at the slightest noise. Ruth, being a good wife, tried to make things easy for him.

"For millions," he had cried. "For the world!"

Ruth dipped grits onto the handpainted breakfast plates her mother had given her and pondered her husband's choice of sermons. He was not a stupid man, but she could not see how his words would help the crisis-stricken people of the community. What was that football saying: "the best defense is a good offense?" — or maybe, "the best offense is a good defense?"

She really didn't know his reasoning but doubted its good sense. Then she stopped. Pivoted back from where she had poured the orange juice into small glasses, she peered at the cat that lounged beneath the table. "Clea?" she questioned. "Clea?"

The cat winked through drowsy lids and twitched the tip end of her charcoal tail. It was Clea all right. But her eyes, which had been butane blue until that moment, now stared out calmly in dazzling green.

"Oh, my," Ruth whispered, "oh, my."

Ruth had once told a woman friend that she was handy with a needle but bought, occasionally, a housedress or two at the Diana Shop. She sewed Sunday dresses for Caroline in blue print for the summer and red corduroy for the winter. The woman friend asked her where she got her patterns and Ruth explained that she imagined the image she wanted and then cut a pattern out of newspaper to match it. She had been imagining images for years. Like her husband Curtis, Ruth saw things ahead of themselves. So when she said to the potholder on the wall, after shooing Clea out the back door, "I don't want to see anything more, or less, in this house today," she knew she was wasting her breath.

"Don't worry," Curtis had soothed her at breakfast yesterday. "Khrushchev'll back down. He knows he's beat." Then he had gone off to lecture the congregation on world mission, taking as his scripture passage, "The harvest truly is plenteous, but the laborers are few."

Ruth shook her head in fuddlement.

It seemed like every time they rode to town now they'd see the army. Herds of snake-green trucks migrating over the arched bridge of the St. John's River, heading south for Miami and beyond. Once there, what? She imagined the trucks lumbering like a line of June bugs one after the other into the turquoise waters of the Keys, scattering their shells across the coral, leaving behind only a few bubbles of foam and the land in peace. It wasn't likely to happen, she knew, and she shouldn't want it to. "They are our boys," she told herself, and posed William as one of the young soldiers from Fort Benning, gunbelt across his heart and homesick for her Sunday dinners.

A shaft of wind shook the house and rocked the kitchen with buzzing salt.

"It's the changing seasons," Curtis had said when she pointed out the gaps in weather.

"Since when does Florida change like this?" she asked only herself because she wanted to believe him.

"They spit in your eyes and blind you," William told his sister. The children stood in the night shadow of the cedar talking about granddaddy long-legs. Ruth sat on the back porch shelling peas in a roast pan on her lap. The wind had calmed and it seemed like any other late October night, warm enough still to be summer. In the dark, Clea was permitted to curl beneath her mistress's chair.

"Can we go into the garage?" William asked. "We want to look at spiders with my flashlight."

"All right, but watch out for coons around the garbage can," Ruth said.

They strolled across the lawn, a saucer of light moving on the ground before them like an animal. "If you see any," Ruth called after them, "chunk a rock at them." It's funny, she thought, how the children seem to love to flirt with the things that scare them most. As if the worst could never happen.

In a quick breeze that came like a man stepping around the corner, Ruth caught the unexpected scent of fresh oranges and tangerines. It reminded her of all the things she liked best about her home and life. She had smelled it first as a child in Georgia in the crate of fruit sent each January by an uncle. Then her family had moved to the small Florida town and she had watched the white knobs of blossoms grow into oranges on their own backyard tree. Curtis had brought her navels from the Indian River when William was born and the ladies of the Women's Missionary Union had kindly bragged over her apple, orange, and pecan salad, to put her — the preacher's young wife — at ease. Ease — that's what she needed now but had not known for so long that the smell of oranges seemed like a ghost from another time. "I guess I just need an aspirin," Ruth told herself.

The peas didn't occupy her long and she was nearly finished when Curtis came looking for her. He had been watching the nightly news.

"Castro is fueling the flames," he said. "He's yelping that Khruschev's sold him out."

"What will he do?" asked Ruth. "Castro — I mean — what will he do now?"

"It's like betting on the devil. No telling." He sat in the chair beside her and picked a single pea from the pan. "But we'll see. We can face them down if we have to."

Her husband was a narrow man, arched slightly like a leaf, shoulders stooping, but with a handsome face and blue eyes. Clea's blue. Startled by the thought, Ruth leaned forward and peered close at Curtis's face but couldn't tell if his eyes had changed. Not in the dark.

"Ruth," he said, and she twitched at the tone. It was the preacher's tenor of I've-got-something-of-grave- import-and-long-reaching-effects-to-tell-you. She held still and her husband told her in a few sentences that he hadn't been able to sleep the past few nights because God had been knocking at his heart. He had been literally tossled about until he gave in and listened. What did he hear?

"I've heard The Call," he said, pointing the pea at himself.

"The Call?"

"For mission."

"Where?" Ruth asked.

"Japan."

"Japan?"

"Japan," the preacher said eagerly. "We're going to Japan."

"Oh, my God," Ruth said. "What next?"

His eyes shone blue as ever, bright as water. It must be a full moon then, she thought, and stuck her head out the back door. The night was black, even the shadows chased away.

Curtis sat like an excited little boy, hands clasped before him on the kitchen table. She was giving him a glass of milk to settle his stomach.

"Don't you see, Ruth?" he pleaded. "Castro preaches lies that he would brainwash everyone with, if he could. That's why communism is so dangerous. It's out-and-out atheism and it doesn't even pretend not to be. Can you believe it? They say outright that God is dead. How could anyone believe a German idea after World War II? But they believe it and they want the whole world to believe it with them. Those Russians put cows in churches and oats in synagogues."

He prattled on and Ruth nodded her head. She didn't pay much attention because she was trying to follow a strange tapping noise from the west. She clutched her elbows, paced the kitchen, and worried, "Where could that sound be coming from?"

"I think world mission is the best defense against this threat," Curtis droned. "We got to fight fire with fire."

"What threat?" Ruth asked and noticed that once again Curtis's shirt label stuck straight up out of his collar. Just like William.

"The Bomb," he said.

"Oh," said Ruth. "I thought you meant communism." She slipped the white flap back in place with a fast hand.

"One and the same," Curtis said. It seemed that he had begun to catch the drift of his wife's nerves, as if he picked up something from the touch of his neck hairs.

"Curtis, listen." She pointed to the door. "What's that sound?"

"I don't hear anything."

"Come to the door."

He didn't much like posing at the door, head cocked, but he did, nevertheless, because he too felt the bumps of a faraway crackling.

"Lake George," he said.

"Oh, the bombing range," Ruth cried, remembering what she already knew. They had gone fishing near there, in a river called the Oklawaha, about a year before. The preacher turned and watched her and his blue eyes seemed to click a shade darker.

"The navy must be getting ready," he said. "That's another reason," and he squeezed her arm below the elbow, "we should leave."

"Why? What does that . . . "

"Japan's a lot farther from Cuba than we are."

Ruth knew then that Curtis understood her fear was more than conversation about the weather — but a blade real and deep inside her like a sheet of metal that would ring out if he touched it. They stood face to face in the yellow kitchen light, not moving. But Ruth felt they were circling one another, eyes locked — each sizing up the other.

"Call the children in," she said finally. "They're watching spiders in the dark."

"Men act and women react," her mother had explained to Ruth the day before her marriage. "That's not to say you can't channel their actions. Just remember — let them think they're doing it all." Her mother had given her that piece of advice, as a kind of gift, Ruth supposed, along with the hand-painted breakfast plates. For years Ruth had held the plates with their rose tomatoes, fine nets of lettuce, and baby-finger carrots to be more valuable than her mother's twisted outlook. After all, her parents had not enjoyed a happy marriage, and Ruth vowed not to repeat such a hypocritical relationship. If her father wore the pants in the family, her mother chose the fabric, cut the fit, and hitched them to her height. "He wants a house by the river," she confided once to her daughter. "Over there in the wilds. I'm going along with it, but I've told Eva to accidentally drive us by that place on Pine Street." Eva was the real estate agent.

Ruth's opinion of her mother's advice changed gradually over the years as she came to know Curtis more and trust him less. Why did she trust him less? Perhaps she expected too much from him — wisdom and direction and sure handling of their lives. Instead she discovered her husband to be a man inept with the things of the world. It would take him two hours to change a car tire; he had visions of selling catfish or roses to make money; his health was bad and he talked constantly of not getting enough rest. Yet Curtis made the decisions for the family, and Ruth, still a good wife, complied, bit her tongue, and prayed for the best, hoping their luck would change. Then she and Curtis and the children had gone fishing in the Oklawaha — that was a year ago — and the experience had snapped something in her, something that was young and accepting.

She remembered how excited Curtis had been over the trip.

"This is the place to catch bass," he exclaimed. "If they were legal, I could make a fortune selling them to restaurants. But you can't sell game fish."

Among swamp lilies and the "kee-kee-kee" of hidden birds, the family took its outing. The brush came right to the edge of the water and trees atangle with vines and moss slanted over them. Ruth couldn't find the shore beneath the mat of black-purple leaves, roots, and green beads that swayed in the wake of their boat.

"Where are we going to have the picnic?" Ruth asked.

Curtis only nodded and kept them churning down the river, taking them farther and farther into narrower and narrower channels.

William pointed his BB gun into a thicket and fired. A faint ping rang out and a pair of huge blue wings lashed through the bushes and soared above them. Caroline curled up in the bottom of the boat and let out a wail that grew sharper as it ricocheted off the water and dug into the dark of rotten logs.

"Hush now," Ruth crooned. "Look, Carol, a butterfly." A yellow sulphur dipped up and down over the bow, then flapped off into a fan of palmettos, trailing an odor of wild marigolds.

"Watch your heads," Curtis warned. They all ducked to miss an overhanging oak limb.

"Moccasins lay on limbs too," William said, turning his BB rifle up. They had already seen three v-shaped ripples in the river: water moccasins gliding by the boat, straight as sticks, heads slightly up, eyes black as their skin.

"There's one on that log," William cried. Curtis slowed the boat and the boy took aim and fired. The snake drew head and tail together and William fired again.

"Got him!" he said. "Right between the eyes!" By the time Curtis threw the anchor out, they had spotted two otters, a small alligator, and a raccoon up a tree. "A good experience for the children," Ruth told herself nervously, "seeing all this wildlife." Yet she couldn't enjoy the sights herself. Although for a moment she might admire a giant stalk of elephant ears or a white egret or a deep plop in the water, she felt snagged with worry. "What if we are lost?" she wondered. "Ticket-ticket-ticket," a bird sang and Ruth could hear her mother pronouncing "wilds" like it was a word akin to "hyena."

"It's an Indian name," Curtis told the children. "'Oklawaha' means 'silver river.' It runs from a pure spring out of limestone caves, and its water's always cold. At night when the moon's out, it's supposed to shine like a new dime. Some say," and he winked at Ruth, "that it's magic because you can see all the way to the bottom, to the shadows of the fish even. Look! What's that moving there?" And the children leaned far over the gunwale. "You have to look past your own reflection," he said, "it's like a car window at night."

"I see him," Caroline said. "He's swimming in and out of the seaweed."

"How many people can say," Curtis went on, "that they've been in a real jungle, seen an alligator in its natural home, and watched two otters slipping through the water?"

"And all the moccasins," William reminded him. "Yea," Caroline agreed. "And the butterflies."

And how many can say they nearly stayed there forever because they couldn't get out? Ruth had told Curtis at three o'clock that they should leave before the early dark caught them. He wanted to wait just a little while longer. The fish weren't biting, but he knew they were there. In the hot stillness of the September afternoon the children grew restless. Caroline whined about the mosquitoes; William shot empty claps of air — his BBs long gone. Out of boredom and worry Ruth focused on a cocoon the size of her fist. As Curtis cast and re-cast his line, she wondered what sort of animal curled inside the egg waiting for a signal it would give itself to emerge.

Then around four the fishstorm hit. The water seemed as solid and steely as the top of a tin can, a flat reflection of limb shards and white sky. A silver tail cut the surface, a fin flapped, and a small whirlpool started off the bow. "They're starting to feed," Curtis whispered, and his line ripped across the tight face of the river.

Within 40 minutes he had caught eight yearling bass. By six o'clock there were 19 strung gill-to-gill on a yellow cord trailing the boat. Every few minutes, one would thrash and rouse the others, the whole line stirring, scales flicking. "Like a dragon's tail," Caroline said. And the tail kept growing.

"I've never seen anything like it," Curtis cried. "You're luck, honey," he told his wife. "You're luck."

The patch of sun dwindled until there weren't any shadows at all — only a gray light that made it seem you were looking through the tangles in a dust ball. With the fish twirling beneath them in a frenzy to be caught, Curtis wouldn't leave. "I've waited all my life for this," he said. So they lingered, and when the anchor was finally pulled in, caked with a lump of mud on each blade, Ruth had to strain to make out the studs of banana spiders overhead. Their spiky legs were already melting into the trees.

Curtis led them back through waterways hardly wider than the boat. Before all the light leaked out of the air they passed a hollow cypress log that looked like the leg-bone of a dinosaur. Squatting on it, a yellow-green turtle blazed with red eyes at Ruth. When she saw him again, she whispered, "It must be his brother," but the third time, she couldn't deny it was the same animal. "We're lost," she thought. "We're sputtering in circles."

"The Oklawaha," Curtis had said earlier, "is one of the few wild rivers left in the South. No dams, no diversions."

"So what?" Ruth snapped back in her mind. "So the river's wild — that only means it spills over the land like varicose veins full of snakes and leaf garbage."

"We're lost," Caroline cried.

"Crybaby," William said, then turned to his father. "You know where you are, don't you, Daddy?"

"Sure I do," Curtis said, and handed the flash¬ light to Ruth. "Shine that ahead so I can see the channel."

The light stretched thin, picking a bare line through the bushes, exploring the blue veins in a leaf, slashing over the hyacinths. She held it steady until it skimmed a cypress log and struck two red discs.

"Men bungle," her mother had warned, "and women have to live and suffer with their mistakes."

"Forever?" Ruth moaned that night in the Oklawaha, sending her plea out from the thicket, up a blank sky, and through the light-years that stretch between the living and the dead.

In answer, the red-eyed turtle came round like a pinwheel the fourth time. William scrambled up the flashlight when Ruth dropped it and shone it again on the log. "Ah, it ain't anything, mother," he comforted. "Just an old turtle. That's all." Inside her, Ruth could feel an itch of nerves starting down deep and blossoming like the first small bubbles shooting up in a pot of water about to boil. "So this is the cap to it all," Ruth told herself. "We're lost and he says he knows the way."

For two more hours they meandered about the swamp until Caroline was beyond crying and both children were swollen with mosquito welts. Ruth stayed calm, not thinking of the snakes below them, the gnats around them, or the darkness all over them. She didn't even turn her head back to Curtis when they heard the magnificent squall in the bush and William whispered, low and awed, "Panther. Daddy. Panther."

Ruth concentrated on her itch. She scratched evenly, lightly, ankles and legs and sides and arms and neck and even earlobes and eyelids. By the time Curtis found the channel, her skin had sprouted reddish-white blisters.

"I could say things now before the children that would scald him, humiliate him, kill him," she thought, and remembered the time her father, an enormous man, had stumbled drunk to the front steps. "Help your father in, Ruth Anne," her mother had ordered, knowing the small girl's gestures would only increase the father's guilt.

"You have power," her mother told her the day before the wedding, "but it's a quiet power. Hidden. Remember that."

The words drifted back to her as they moved swiftly over the dark water, the fast air cooling her skin.

"The river's not silver like a new dime," Caroline told her father.

"No moon," Curtis replied gloomily. "Not even a star out tonight."

"No," thought Ruth. "No moon and all the shadows are ones you'd rather not see." Ruth had begun to accept the fact that she was her mother's daughter and that things she would not have thought of doing to Curtis when she was younger she just might do now after all.

"There may be oranges in the grove," Curtis had warned the congregation of the Pomona Park Baptist Church, "but they will rot on the bough unless there are hands to harvest them." He had said that in church yesterday, the day before the morning of hail and Clea's eyes, the day before the night tapping in the west.

The Call to Japan. Like the other shoe falling, the sermon finally made sense to Ruth. While she and the other ladies were scanning Winn Dixie aisles for fallout supplies, the men went on flirting with visions of worlds conquered. Get them before they get you. Japan. She uttered a crabby little laugh and wondered if the women in Hiroshima during the final minutes still worried over how many cans of tomato soup the family would need. Ruth had eight, plus three bags of flour, two cans of grape juice, five cans of pink salmon, four green peas, three spams, grits, rice, and seven cans of spaghetti. The TV told her canned goods were the best since they weren't as likely to soak up radiation.

Curtis, in a typical act of unthinking generosity, had tried to donate the whole store to a migrant family.

"Food won't save us," he had snapped when she headed him off at the pantry.

"That's for your children. They may need it one of these days."

"There are children this minute who need it."

Ruth hated him then for making her the selfish one. For forcing her to decide between her children and another woman's. Her skin broke out in her swamp itch and she retreated to sit for long stretches soaking in a tub of warm water and baking soda.

"Ruth?" he bargained through the closed door, "It's all right. I called the deacons and we're taking up a collection." And he thought that was that. She could squirrel away all the food she wanted so why didn't she pull the plug and stop the scratching?

"Nerves," she told her women friends. "I lie on a bed of stinging nettles at night."

"We're all the same," they consoled. "I never did like hairy men," one answered, "and that Castro is the hairiest man I've seen." Ruth understood the feeling, coming herself from a family of women with a deep resentment against moustaches and beards. But, and she didn't tell this to the women, she wasn't itching just from worry over the black-haired communists to the south. The war they threatened was only one sign of the helplessness that pervaded her life. Someone she would never know — a man, or two or three or 20 men — would decide for or against her life and the lives of Caroline and William and her husband.

"I feel The Call," Curtis repeated now, after the children were settled in bed and he had joined Ruth again in the kitchen.

Ruth's elbow began to itch. "Well, I don't," she said frankly, and surprised herself in saying it. In the year since the fishing trip, she had become sly like her mother. "Never tell them what you want," the older woman had said, "unless you know already it's what they don't mind giving." Ruth had begun to suspect the preacher of things, mistrusted his motives, tracked his steps during the day. "Where were you this afternoon — I thought you were supposed to be visiting Mr. Wilters?" and "Why did Mrs. Tennant smile at you like a cat?"

The preacher lifted his eyebrows. "It's not important for you to hear The Call. Your place is with me."

She backed off then, scratched her wrist, and gazed out the back door.

"The hibiscus are blooming now — at night," she said. "They should be closed up."

"It's the warm weather," Curtis said impatiently. "But that's not the question. Are you going to pray about Japan, or not?"

Ruth turned back to the man with the stooped shoulders and believed for a moment that was all he wanted. She had a choice. She could pray and if her searchings didn't turn up anything, she could say, "No, not this time." There was a straight road and a crooked road and he was offering her the straight: a clean, honest answer one way or the other.

"You know, dear," he said, "storing food against this thing is like building a dinghy to ride a tidal wave."

"You can't eat words."

"But you can," he exclaimed. "Words can change the world."

The preacher went off to toss in his bed, leaving her with the admonition that the world faced a choice between Castro and Christ.

"I'm calling the Foreign Mission Board tomorrow," he said, kissing her cheek.

They were going. The itch spread to the inside of Ruth's thighs and across her knees. They were going.

But there was always her mother's way. Ruth imagined how she would handle it: get on the phone to the Southern Baptist Convention. Tell them her husband suffers a heart condition he won't admit because of his fervor to serve. Tell them also that two children are involved. Then wait for the politely-worded note from the secretary that would explain how the preacher filled a crucial niche in their "home missions." "We can't afford to lose you," it would say.

Ruth switched off the light in the kitchen, brushed her hair back with her palms, and walked out the back door. The small tricks and bitchery of the past year had not prepared her for this: she was frightened at the size of what she could do and Curtis never knowing. Words can change the world, he had said. Not used to the dark, she edged the past year had not prepared her for this: she was frightened at the size of what she could do and Curtis never knowing. Words can change the world, he had said. Not used to the dark, she edged her way down the steps. "Japan," she said, to see how it sounded for a word meaning "home." Japan. It didn't sound good. Pomona Park was home. She remembered the smell of oranges that had come to her earlier in the evening. This was home, and to pick up and leave and go to a place where she had no family, no friends, not even a language she could speak, was craziness. Craziness. Even with Cuba she didn't want to leave. She knew too, from the very first, that Cuba was just an excuse; Curtis was playing against her fear. When he wanted something, he concocted reasons afterward.

With nothing more than an urge to use her hands, to actually do something other than worry, Ruth moved to the flower bed beside the door, dropped to her knees, and began cleaning away the debris and tangles. It was an act of faith to weed the geraniums at night: she could see nothing and her fingers were likely to collide with anything. Nevertheless, Ruth did what her mother had never allowed — she pushed her bare hands down into the soil and weeded. She could feel her mother's disapproval leaning over her: "Ah, your fingernails," the shadow nagged, "why don't you wear gloves?" Ruth jerked back from a small, slick tube, ringed and stiff. It didn't move, but she knew it was alive. And she couldn't explain the presence of fur on the back of some fallen leaves. Her fingers snagged roots of stray grass blades, stalky weeds, three-leaf clover. She sieved through shards of wood and damp pine needles. Bending over to sniff the mint plant, she discovered, by feel, small craters around it: she guessed they were ant-lion traps. "Doodle-bugs," the children called them. She pulled up more weeds, shaking shells free and the chalky, delicate skeleton of a small animal, perhaps a bird since there was the feel of a beak, but it could have been a tooth. Something pinched her on the web of flesh between her thumb and forefinger, and later, a piece of earth slid underneath her hand and a creature, probably a snake, shot past her leg. She scooped out small packets of dirt, patiently traced root runners, and paused only to scratch herself. Her fingers tried to read the colors of the soil: she felt dark blue, and deep purple, and stitches of red. It was a rich soil.

"So why do you starve my geraniums?" she asked.

Near the end of the bed, she found tiny dents on the surface, much finer than the ant lion traps. "Ah," she remembered, "the hail this morning." Ruth unbent herself then and stood, scratched her nose and with a little cry, recalled the dirt on her hands and beneath her nails.

"I must have marks all over me," she thought and imagined the black spots her fingers had left on her arms and chin, forehead and calves. "Paw prints," she said, and laughed at the picture. "What the children would say!" But Ruth didn't rush inside to wash herself. She stood relaxed and relieved after working, breathing the night air, and feeling better than she had all day. "Work is what I need," she said. And when the clean, fastidious ghost of her mother began frowning, she told it right off: "I'll take a bath when I'm ready."

The sense of rebellion fired her and Ruth laughed again. She laughed because she knew she was not her mother. "I am someone else," she said, and the words seemed to contain all the strength and decision she wanted for herself and for the whole world, if it needed it. "I am someone else."

Slapping the dirt off the hem of her dress, Ruth walked back to the porch. She still didn't know what she was going to do, but she knew she wasn't going to call Nashville in the morning.

"Enough reacting," she said, brushing a sand gnat away from her eye. Clea made up to her softly and Ruth rubbed her with one knuckle. "Friends again?" she asked the cat. Ruth sat and closed her eyes then, and dozed off in a glad tiredness. When she woke, she saw that the moon had slipped up from somewhere, and in its light the back yard sat before her like a stone, sharp and hard in cedars and sandspurs. A small purple lizard whipped by her toes and Clea pounced after it. "Come back," she called and called again to the cat with the blue-into-green eyes. "The sea may be coming and you don't like water." But the cat stayed gone, and Ruth was alone when the sky turned brown and she started, uncertain and tentative, practicing for the day. "I'm staying here," she said and licked the salt from her lips. "I'm staying here," she said again. "You can go, but I'm staying here." Beyond her, the cedars shook and the hibiscus trembled.

Tags

Cheryl Hiers

Cheryl Hiers is a writer who lives in Ormond Beach, Florida. (1983)

Born in North Carolina and raised in Florida, Cheryl Hiers is currently doing graduate work in English at Vanderbilt University. “A Citizen of Florida” is the title story of the collection which forms her master’s thesis. (1981)