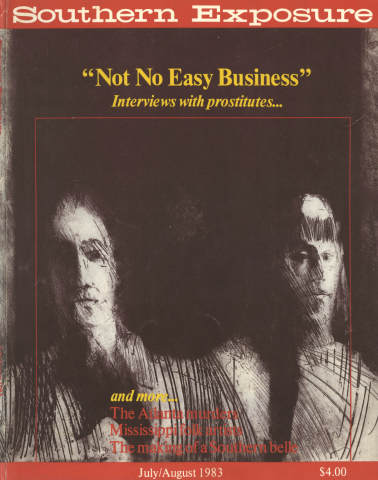

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 4, "'Not No Easy Business:' Interviews with prostitutes." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

I was a virgin when I got married. All my friends were too, or at least they never told me if they weren't. Nice Southern girls did not go "all the way." We just drove boys crazy, blowing in their ears, letting them feel our bosoms, then shutting the door in their panting faces. The war changed everything and saved a lot of prostate glands.

The Depression laid on strong in Montgomery, Alabama, in the late 1930s, and there was no money to buy anything or go anywhere, making for a slow and boring life for privileged white teenagers in a sleepy South between two wars. All the big migrations were yet to come and the people with whom we grew up were the friends we thought we would see the rest of our lives. We would be in each others' weddings and be godmothers to each others' babies, just like our mothers before us. Girls grew into women aping their mothers, and boys shouldered fishing rods and guns under the tutelage of their fathers, just like always.

Nothing much happened after school hours for girls in 1938, when we were 13 and full of beans. Competitive sports were for boys and we were content to cheer for the home team from the sidelines. Each pert or pitiful girl-child dreamed the only dream Southern girls knew to dream about the male sex: that the broadest available hunk of shoulders would swagger over and choose her to take to the drive-in and neck.

Too restless to sit before the radio, we spent a lot of our free time between the ages of 12 and 14 in Doc's drugstore, flirting and peeping at the dirty books the drugstore cowboys flashed around behind the shelves of Castoria and Sloan's liniment. The repulsive, cheap pictures of comic strip characters like Dick Tracy and Little Orphan Annie screwing each other gave us a charge.

With no money and nowhere to go, we often "parked" at the houses of friends who had families good for laughs and eats.

Miss Rose Herndon was my best friend Winkie's mother. Rose stayed in bed all day, a female sight not unusual in our circle. Rose suffered from punishing "migraines" whenever she exerted herself to go to the grocery or drive the car. After Winkie was born, .she went to bed for good. When her husband, Sam, came home from the country club around nine or 10 at night, she departed her bed, put on a wrapper and cooked him a hot dinner, all the while cursing "bastard" under her breath.

Sprawled on her bed, summer and winter, with us stretched out on the floor, Rose wove wonderful tales of her girlhood in a house full of sisters and the comings and goings of "beau lovers." Storytelling excited Rose. Her pale face took on a fevered pink, as she called out frequently in a bright, strong voice, "Loula, bring me a beer." She enjoyed visualizing us as grown-up ladies and often pulled me up from the floor toward the long gold-leaf pier mirror standing at the foot of the bed. Snatching my hair back or piling it up on top and bending her head to look critically, she would say, "My, but you are gonna be a knockout, sweetheart. Some man is gonna lose his mind over you." I believed her blandishments.

Rose never had any cash, but she could charge at the drugstore. Several times a week she would call out to Uncle T, the old black man who swept around and waited on Loula, "T, go get these children some ice cream and tell Doc to send me $25." A curious child, I questioned this arrangement. "What does it say on the bill, Miss Rose? Does it say, '$100 worth of ice cream,' or what?" "No, darlin," she added, "he is the banker for the neighborhood wives. If Sam complains about the amount of medicine charged, I just tell him my migraines were worse. How would he know the difference? He is never home." And he rarely was.

Rose had an Aunt Carrie, who rustled in to sit on the bed and visit. She was a tall, skinny, elegant old lady of around 50 when we were 12. We loved her visits when she swept in bearing the fresh apple muffins which were her cook's specialty. Dressed in romantic gray or purple chiffon that billowed out behind as she passed in front of the electric fan and was always just back from a cruise on the Nile or full of talk about her next archaeological dig in Greece, she dazzled us with her exotic glamor.

"Was Aunt Carrie ever married?" I asked Rose after that lady's flowing departure one afternoon. "Yes, my precious, but long ago and not for long."

"How long?" we chorused. "Less than a week," whispered Rose, averting her eyes. "

A week! What happened?"

Clearing her throat, Rose answered hesitantly, "It was one of those things you just don't ask. It was so long ago. I was your age and I remember. . . ."

"Go on, Mother," wailed Winkie.

"Well, something happened on the honeymoon."

"What was it?" insisted Winkie.

Rose could not bring herself to divulge Carrie's secret. "A beer, Loula." Panting a little and barely whispering, she lay back murmuring, "Darlings, I have a beast of a headache." Drawing a wet cloth over her eyes from a bowl of water on the bedside table, she signaled the end of that conversation, whispering weakly, "It was so long ago."

My friend Tina's was fascinating house to visit because of her mother, Florida — a small, blond china doll with a brain like a steel trap. This was during the Depression, and Florida's land was in south Alabama with taxes to pay. The red-brick-columned "Beauvoir" — romantically placed among giant water oaks and hung with imported gray moss — was heavily mortgaged. There seemed to be no earthly way Florida could get the money she needed. But even with her worries, she found time to hope we would drive men crazy. She would often grab one of us as we ran through the house and gently pat our emerging bosoms. "My, but it looks as if these will grow into small cantaloupes, angel. You are going to drive the men crazy."

Florida's husband Oliver was a patrician loser who drank too much, and had "given up." On hot summer afternoons, Florida paced the upstairs hall in her girdle trying to think of a way to save the plantation. In the late summer of 1938, she found it. We sat on her bed while she packed lovely, thin, flowing pastel dresses and two big hats, decorated with roses. "I am going to Long Island for the weekend," she told us.

When she returned, she looked different, more relaxed. There was an air of mystery about her. When we asked if she had a good time, she looked obliquely at us as if she held a secret. That mystery was quickly solved. Within two weeks a short, portly and stern-looking older man, Mr. Hay, appeared in a long, chauffeur-driven, black car. Florida and her mother Gin had put on their long, filmy, low-cut frocks to entertain him on the veranda. It must have worked, for within three months Florida had divorced the loser and married a winner.

Mr. Hay had a town house on East 64th Street in New York City and a large estate in Locust Valley, Long Island. Florida's clothes got grander, her furs silkier, her body hung with jewels. The last time I saw her (she died of a heart attack soon after) was in the house on 64th Street. She was at one end of the long dining table and Mr. Hay was at the far end. I was sitting on her right. She proceeded to tell me that she simply could not stand Mr. Hay. He was tightfisted, she said. There was a house in Nassau she wanted, but he said no. About that time, Mr. Hay asked, down the length of the table, "Florida, what are you saying?" Butter wouldn't melt in Florida's mouth: "Darling, I was just telling Titter how much I loved you."

Lucy Belle Pearman was my second-best friend. Pudgy, fat, with a soft, white body that reminded me of a featherless pigeon, Lucy Belle (another only child) was the apple of her parents' eyes. Mr. Pearman, or Big Roy as we called him, did not appear to work and their source of income was a mystery. Somewhere along the way, I was given to understand that Big Velma, Lucy Belle's mother, had the money. Her people had bought land cheap down on the Gulf Coast where Panama City grew and down Mobile way, where the highway was coming through.

Big Roy might have worked at something, but he was always home when we got home from school about three, sitting in his undershirt by the radio drinking a beer. Our routine in their house comprised a dash to the kitchen to wolf down a piece of Big V's sunshine cake and a cola. Then back for a tease from Roy. "Come here, sugar," he winked at me. "Close your eyes and hold out your hand." Knowing well the next move, I still giggled and squeezed my eyelids together. "Here's a present from Uncle Roy," and he dumped warm ashes from his smelly cigar into my outstretched hand. This had been no surprise since the first time, but I went along with the "trick" because it seemed a friendly gesture. It also gave Lucy Belle and me reason to release all that pre-pubescent pent-up energy. Screaming with laughter, the next move was to jump on him and swap tickles.

My father never had any time to take us anywhere but Roy Pearman did. Around age 13, we hit on a pastime that he enjoyed as much as we. The Red Light District was well defined in Montgomery, on the edge of "nigger town," and the trick was to drive slowly along the street with no car lights. The women stood in the doorways of the seedy houses barely covered by flimsy kimonos, their limbs in silhouette from the dim light behind. Occasionally men would stagger out, but nobody we knew.

In our still-small town, the names of these "ladies of the evening" as my mother delicately called them, were known to all. On Wednesday night when Velma and Roy played bridge, Lucy Belle spent the night at my house and we entertained ourselves by calling the "ladies." Holding a handkerchief over the receiver to muffle the voice, the caller attempted a low, male sound and whispered something devilish like, "How much does it cost under water?" Or, "Do you charge half price for midgets?" The poor victim was not destined to suffer long as we invariably got the giggles and hung up, so convulsed with laughter that we often wet our pants. We had no idea, of course, what these women really did or even how the sex act occurred. All our information was acquired by hearsay or from those dirty books passed around by the drugstore cowboys.

If I learned anything about sex at all in those protected years it was from my father and certainly not on purpose. Papa was a self-made man, an early rendition of a good old boy. From a plain south Alabama country family, orphaned as a baby, he was raised by older brothers and sisters, learning only to survive. After one year in college, the money ran out and he had to go to work. Good-looking, bawdy-talking, and oozing charm, he snowed the patrician lady who became my mother. She was soft, gentle, and submissive, and never quite got over marrying a man with whom she had so little in common.

Papa was an earthy man and loved horse-play. Grabbing me in his huge farmer-like hands, pinning me hard against his chest in a steel grip, he blew in my ears, as I struggled helplessly, yelping with joy at the undocumented sensation. I never got too old to sit on his lap. Long after other fathers had self-consciously ceased this familial intimacy, Papa still pulled me down for snuggles. After age 12 and blossoming bosoms, it was embarrassing for me, but not for him. He never seemed shy that his breath came more quickly with me so close and for that I have come to be grateful. I learned what a man smelled like and what close proximity did in a hurry to his glands. My father taught me in a crude but valid way that sexual response is as natural as breathing.

When we got to be 13 or 14, the picture show took up much of our time. We'd sit on the back row of the balcony, learning to soul kiss in the blackness. When a boy's hand started to steal up the thigh it was time to slap him, be insulted (of course) but not leave. At roadside joints with names like Moonwinks and The Green Lantern, dancing close to Tommy Dorsey's "Marie," when a male hand got hot on my back and I was pressed so close I could feel something hard against my leg, I was satisfied. I had driven him crazy. That was what girls were supposed to do to boys.

"Do you know what boys do when they get all heated up?" Winkie asked one sweltering summer day, as we lay on our stomachs on the cool marble hall floor at my house. "What?" I asked, not really expecting her to know. "They take a room at the Jeff Davis Hotel. The cops don't bother the hotel, so the bellboy can bring in a couple of floozies." She wrinkled her nose in distaste. "It's cheaper than those old whore houses, you know, the ones Big Roy used to drive us by. This way with one floozie, they can pro-rate expenses."

Then there were always those stories about the fellow who, after heavy necking with his date on the back seat, could stand it no more. Turning up his collar, he rushes painfully off to the whore house, only to return with a "social disease," which meant no nice girl would ever go out with him again.

Ethel was the most worldly girl in our crowd. She had been known to order a highball on a date; she read books like Moby Dick and had been to Chicago to the World's Fair. As we finished our sophomore year in high school, she announced, "I have had it with Hickville. I'm heading toward those bright lights up north." (When my father heard the news, he said scornfully, "Well, she can afford it. Her old man is the biggest mortgage banker in town. He foreclosed on all the widows and orphans who fell behind in their payments in these hard times.")

At the train station, when Ethel left on the old Crescent Limited, we cried and took on as if she was going off to slave labor in Siberia. At the long-anticipated spend-the-night party on her return at Christmas, she told us the big news. "I'm not a virgin any more," she proudly proclaimed, brushing her auburn pageboy into place. After our communal gasp, she continued smoothly, "Daddy reserved a drawing room for me on the Crescent, because I had some studying to do. I took my math book to the diner for dinner and there was this cute young steward. He offered to help me with that horrible 'trig,' and I could have used some, but," she laughed, "I didn't get THAT kind of help. After he finished up in the diner he came back to my room and brought a bottle of Early Times. We had a ball. He was really good at it," she said, rolling her eyes. Aghast, we stared speechless at our friend. Now she was different, nothing would ever be the same. All night long, from time to time, the shock flattened Winkie, Tina, Lucy Belle, and me, causing us to wail and weep hysterically for our friend's loss, while she lay sleeping with a smile on her face. Was it her loss we mourned, or all those pent-up emotions of our own? So much emotion, so few outlets.

Mother finally brought herself to tell me the facts of life, after a fashion, when I was 15 and had already learned all the wrong things. It was too late to tell me, "If you let him go too far, you will have a baby." Or "Sister, you know boys don't marry girls with whom they have had their way." This knowledge had been part of my bones, growing up Southern in the '30s. Unspoken, but rooted as firmly in the female consciousness as if in cement, was the dictum, "Nice girls don't go all the way."

The knowledge that such truisms had scant basis in fact made no impression on my psyche. Although I saw with my own eyes the 18-year-old bride, Bess Kirksey, bulge down the aisle of St. Martin's Episcopal Church behind her bouquet of Talisman roses at high noon, I was still shocked when the eight-pound baby arrived less than six months later. Mother defended Bess when Lucy Belle, Tina, and I came back snickering from the wedding. She said, "The child never had a chance; her parents are divorced. Her poor mother takes in sewing to try to support those three children. That sorry father just walked off and left her." I knew that to my mother and her generation divorce was indulged in only by lesser mortals with no social position to protect. Mother meant that Bess had not had a proper upbringing, so she did not know any better.

The only official word my friends and I received on sex was negative. The lifelines thrown to us by family, church, and school were inadequate and fraudulent. We were told that men were objects to tease, torment, tantalize, and use for a permanent meal ticket. Protected, sheltered, and lied to, we realized our main object was to get a husband. If we dangled our charms just out of reach before their hungry eyes, they would go out of their minds with desire for the unattainable, and then they might seek the prize through the one and only legal means, sacred marriage.

Tags

Marie Stokes Jemison

Marie Stokes Jemison says she was raised to be a Southern belle. In December of 1955 she was moved to become involved in the Civil Rights Movement by the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Jemison lives in Birmingham where she helped create the Southern Women's Archives at the public library. (1983)