"It Seems to Help Me Bear It Better When She Knows About It:" A Network of Women Friends in Watson, Arkansas, 1890-91

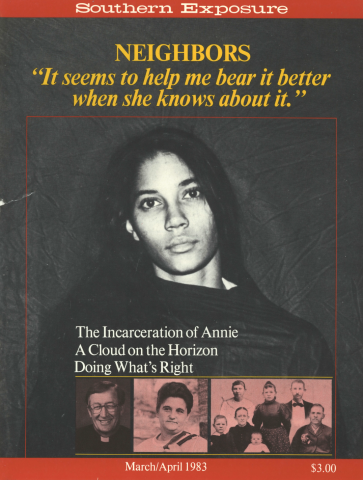

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 2, "Neighbors." Find more from that issue here.

One of the most destructive messages passed on to young girls implies that the spirit of competition born of the quest for the "most desirable" boyfriend, and later husband, will remain with them all their lives; that they will, in fact, see other women as the enemy. Furthermore, the myth of the Southern Belle coupled with the women-are-the-enemy myth accuses Southern women of having greater hostility toward each other than have our sisters in the North, East and West. Southern history, when it deals with women at all, focuses on the accomplishments of unusual women or women in unusual times under the stress, say, of civil war; all but the more basic relationships are ignored. Southern literature, when it focuses on the lives of women, tends to further the myth of cutthroat competition and dislike.

So when the current phase of the women's movement in the 1960s and '70s fostered support groups, it came as a surprise to many that women found such pleasure in cooperation. Feminist influence has weakened the old cultural myths of competition among women to some degree, but young women are still being taught, somehow, to distrust each other.

As a cultural historian and a teacher of regional women's literature, I have had an opportunity to read Southern women's private documents — letters and diaries that escape attention because they concern the humdrum of daily existence rather than the drama of history in the making. In these documents, I have found the truth about relationships among Southern women: for most of their lives, their best friends are other women. And they know it. Nowhere does this seem more evident than among wives — the very group who should, according to the myth, be most reliant on men for their emotional support.

The friends discussed here lived in the late 1800s in a tiny town in the Arkansas/Mississippi delta region of Arkansas. One of them, Nannie Stillwell Jackson, kept a diary in which she recorded the details of their daily lives. I have recently edited this diary for the University of Arkansas Press under the title Vinegar Pie and Chicken Bread: A Woman's Diary of Life in the Rural South in 1890-1891.

Nannie Jackson's diary records the dull and isolated life in a town whose only connection with the rest of the world was a dirt road so rough and muddy that each leg of the 20-mile trip to the county seat and back required an overnight stay. Supplies came by steamboat to Red Fork, a port on the Arkansas River three miles away. There was no railroad or telegraph office; daily mail service was not instituted until 1890. Most of Watson's residents were families of small farmers and the merchants who supplied them.

For the most part, money was scarce. It was especially scarce in the household of W.T. and Nannie Stillwell Jackson, whose 140 acres of land seem to have been either uncleared or under water too much of the time to be very profitable.

In 1889, Nannie Stillwell, a widow with two little girls and few financial resources, filled her desperate need for a breadwinner by marrying W.T. Jackson, a young man not only "beneath" her but 20 years her junior. "Mr. Jackson," as she invariably calls him, was practically illiterate and capable only of working the plot of land they owned, doing odd jobs around the neighborhood, and butchering animals to sell for meat.

Nannie, on the other hand, was a woman of some education. Her handwriting is neat and clear and she frequently wrote letters for those who could not do it themselves. An avid reader, she even read aloud to her husband when she could get him to sit still.

Nannie's diary indicates that the relations between the Jacksons were strained and sometimes stormy. In fact, not one shred of affection or concern for his well-being is expressed in the entire diary. She shared a house, bed and marriage with Mr. Jackson; emotionally, she lived in a world of females: her daughters Lizzie and Sue and a group of some 20 women who formed a network of friendship and support.

Setting aside the financial considerations that made a husband necessary, if all references to men were deleted from Nannie Jackson's diary, her life would not appear substantially different. But it is impossible to imagine it without women. Judging from the evidence in this diary, contemporary women's support groups are an attempt to recover a tradition in women's lifestyles.

At the beginning of the diary, Nannie is 36 years old. Her best friend, Fannie Morgan, is the 19-year-old wife of a man 17 years her senior. Fannie has recently lost a baby, and Nannie Jackson is most solicitous and caring toward her. They share a great many things: food, starch, household chores and their troubles.

Thursday, June 19th, 1890: I baked some chicken bread for Fannie & some for myself, & she gave me some dried apples & I baked 2 pies she gave me one & she took the other I made starch for her & me too, & starched my clothes & ironed the plain clothes & got dinner.

This friendship threatened Mr. Jackson and he tried to curb it. But Nannie valued rewards of the relationship more than his approval.

Friday, June 27th, 1890: I did some patching for Fannie today and took it to her she washed again yesterday & ironed up everything today I also took 2 boxes of moss & set out in a box for her, when I came back Mr. Jackson got mad at me for going there 3 times this evening said I went to talk about him & said I was working for nothing but to get him & Mr. Morgan in a row, & to make trouble between them & I just talk to Fannie and tell her my troubles because it seems to help me bear it better when she knows about it. I shall tell her whenever I feel like it.

And tell her she does. When she feels sick and depressed, for example, she asks Fannie to make sure that all of her possessions go to Lizzie and Sue and that she be buried next to Mr. Stillwell, her first husband, if she should die.

The relationship with Fannie is as close as the tie between very close sisters. Nannie is as concerned about sickness in Fannie's household as in her own, and she seldom makes a special dish without taking some to Fannie. Presents of food to each other are considered personal presents not meant to be shared by the family at mealtime but to be eaten on the spot.

When one of Nannie's circle of friends is ill or has an unusually heavy load of work to do, they all pitch in to help:

Thursday, June 19th, 1890: Clear and warm, very warm. Lizzie is a heap better. Today I went up and washed dishes for Fannie and helped her so she could get an early start to washing for she had such a big washing. Sue churned for her. Miss Nellie Smithee helped her wash and they got done by 2 o 'clock.

The generosity of such acts of kindness should be measured by the heaviness of Nannie's own work load. She makes all the clothes, including underwear, for herself and two daughters, as well as shirts, nightshirts and underclothes for Mr. Jackson. She also makes sheets, towels and pillowcases from unbleached domestic cloth. All her cooking is done on a wood-fired stove for which she must carry wood daily.

Nannie washes all their clothes with water heated outside in an iron pot. They are scrubbed by hand on a rub board with homemade lye soap, rinsed through two tubs of cold water, then starched stiff as a board, hung on a line to dry, and later ironed with irons weighing from five to 10 pounds each which have to be heated on the stove. The laundry suds are never thrown away; they are used to scour the kitchen floor. Her wash water must be carried from the bayou 50 feet away if there is not enough water in the rain barrels.

And of course, three meals a day must be cooked. No packaged food is used, no bakery bread. There is a rare can of storebought fruit only when somebody is sick and deserves a special treat. The garden is Nannie's purlieu, as well as the milk cow and the chickens.

Since this is swamp country, people are frequently very sick. In these days of hospitals and undertakers, it is hard to imagine the almost casual ways of handling the dying and dead before we had facilities to care for them — until we read Nannie's account of the death of a small boy in Watson, when Sue and young Lizzie ride to the graveyard in the wagon with the corpse because it is too far to walk. Then a friend dies during a period of high water in the bayou:

April 14th, 1891: Mrs. Archdale died this morning at 25 minutes to one she suffered a heap before she died and talked sensible up till about 4 or 5 hours before she died. Dove got there before she died but Mr. Jimmie and the doctor never did come . . . Mrs. Morgan, Mrs. Newby, & Mr. Jackson, Kate McNeill & Fannie Totten all set up last night & we dressed her and laid her out . . . The gentlemen have set up with the corpse tonight for Mrs. Gifford can't set up, Mrs. Morgan is sick and the rest of us set up last night . . . Mr. Jackson went to Redfork today to see about getting the coffin made and it has come and Mrs. Archdale is in it.

Wednesday, April 15th, 1891: Cloudy all morning the gentlemen took Mrs. Archdale away & not a lady could go on account of the water. It is falling but slow so slow.

Nannie Jackson's other close friends are Mrs. Chandler, Fannie's mother; Mrs. Nellie Smithee, a widow who works as a live-in domestic worker and field hand; and the Owen sisters, Miss Carrie and Miss Fannie, who board at the Jackson house during the school term while Miss Carrie presides as teacher of the one-room school. The Owen sisters are also like sisters to Nannie, but are not as close as Fannie Morgan — the bond of wifehood is missing.

Miss Carrie is the only financially independent woman in this network. She not only supports herself and presumably her sister, but maintains her own horse, Denmark. Since the average pay for teachers in that county in 1890 was just $252 a year, her independence was limited, but she received the respect due her as an educated woman. While living with the Jacksons, she took part in community social life and joined in the sewing, but she did not perform household chores with the women. Mr. Jackson resented Miss Carrie and complained because Nannie wouldn't reveal their private conversations to him.

The amount of visiting that went on among Nannie and her friends is impressive. This was not a community where people lived close to each other; fields and pastures stretching at least a quarter mile separated their homes. The road was alternately dusty and muddy, and the bayou that runs through the area had to be crossed on a log. After heavy rains had swollen it, the only way across was by boat.

Nannie Jackson's network of friends included black as well as white women. The amount and quality of communication between blacks and whites in the South has always been a shadowy dimension of Southern history and culture; readers unacquainted with the rural South may be surprised at how much interaction actually existed between the races. Nannie expresses affection for several black women, and judging from their gifts and visits to her, the affection is returned. She wrote and received letters for them, traded poultry and dairy produce with them, and did sewing for them. In fact, without knowledge of the race of the women mentioned in this entry, one would have a difficult time sorting things out:

Wednesday, August 6th, 1890: I cut and made one of the aprons for Aunt Francis' grand child & Lizzie & I partly made the basque Aunt Chaney came & washed the dinner dishes . . . Mrs. Chandler, Fannie, Mrs. Watson & Myrtle McEncrow were here a while this evening, Aunt Jane Osburn was here too, & Aunt Mary Williams she brought me a nice mess of squashes for dinner. Carolina Coalman is sick & sent Rosa to me to send her a piece of beef I sent her a bucket full of cold victuals . . . got no letters today wrote one for Aunt Francis to her mother & she took it to the post office, I gave her 50 cents for the 2 chickens she bought & a peck of meal for a dozen eggs.

"Aunt," of course, is the Southern white form of address for an older black woman who deserves respect. Confusion reigns, though, when white women who are really Nannie's aunts or are called aunt by the community are mentioned. The quality of all the aunts' visits is so much the same that their races can only be told by checking the census rolls which categorized people, at least until 1880, as "white," "black" or "mulatto."

Nannie Jackson's diary gives a strong sense of the autonomy of women's culture in Watson — a culture not hostile to that of men, but separate from it and different, with its own center and order. It certainly does not appear to have been a culture of the oppressed but of those who simply share a common experience — an experience which they do not share with men, even their husbands.

It is easy to see how little girls in this community were enculturated to follow in their mothers' footsteps: Lizzie and Sue worked right along with their mother at household chores and spent their free time playing dolls and mimicking the roles of the adult women:

Sunday, June 15th, 1890: Cloudy & warm sun a little, brisk south wind all day, Mr. Jackson went down to Mr. Howells this morning did not stay very long, he came back ate a lunch then went up on the ridge & helped Mr. Morgan to drive home Lilly & Redhead the 2 cows I am to have the milk of, Lilly is mine but Redhead is not she is in Mr. Morgans care and he lets me milk her, I sent Lizzie up to help Fannie clean up this morning & I baked 2 green apple pies & took one to her she sent me some clabber for Mr. Jackson's dinner Lizzie & Sue did not want to go anywhere to day & they stayed home & played with their dolls & had Sunday school & a doll dinner out under the plum tree, I slept some read some & wrote Sister Bettie a long letter fixed up 7 journals to send her & cut a piece out of a paper that Mr. Jackson brought to send her, he has not stayed about the house but very little today, Lizzie Sue & I have had a pleasant day.

The daily lives of our foremothers shed some light on a question I have pondered for years. On the frontier and even years later, as in the time Nannie Jackson was keeping her diary, women and men did many of the same chores around the house and fields. Why did the women learn to cultivate an air of weakness and dependence so that a strong man would take care of them?

It is clear from reading Nannie Jackson's diary that women had no alternative. Since they did not have the employment options of men, either in actuality or in their visions of themselves as workers, mothers conditioned their daughters to be weak. There was a women's culture and a men's culture, which were almost mutually exclusive. A woman's means to gaining a better life lay not in her competence but rather in her ability to attract a husband who could afford to hire some other woman to do the work for her that frontier women and poor women had to do for themselves.

The conditioning process that nurtured this state of affairs is evident in the diary. Nannie's daughters share the housework, chop cotton and carry water to the men in the fields, but it is obvious from the amount of time they spend playing dolls and washing dolls' clothes that, with Nannie's full encouragement, they are playing the games that lead to success in the women's world.

If I had been given the opportunity to deal with Nannie Jackson's diary when I was a young student, my vision of my region's culture and my role in it might have been drastically different. I might have gained at 20 rather than at 48 respect for the enduring qualities of my foremothers, because the processes in which they were involved demanded the same respect as the processes in which their husbands and brothers engaged. I might have better understood what was especially hard to accept at 20 — the necessity mothers felt to mutilate the dreams of young women in order to force them into acceptable patterns of behavior. I might have learned to respect the women's culture for the support it gave to women, rather than to accept the general contempt for it.

Until the old myths are buried once and for all, it will continue to be difficult for women to trust each other, not only in personal relationships but also in responsible positions. Not only will sisterhood remain elusive but also the respect that is necessary before women will support women in high offices or as doctors, lawyers, bankers and politicians.

Tags

Margaret Jones Bolsterli

Margaret Jones Bolsterli is a cultural historian who teaches in the Department of English at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. Her books to date are The Early Community at Bedford Park and Vinegar Pie and Chicken Bread: The Diary of a Woman in the Rural South in 1890- 1891. (1982)