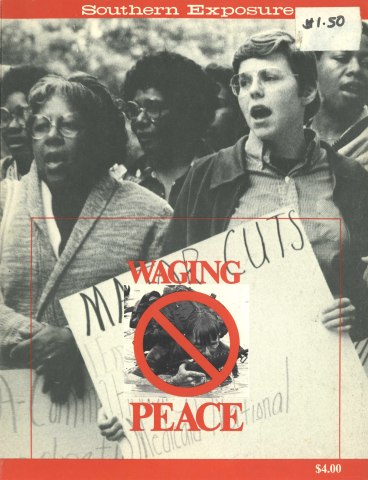

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

The Fund for Investigative Journalism supported research for this article.

In late winter, 1982, Tennier Industries wanted a little something extra from its workers in Huntsville, Tennessee. The company wasn't demanding the usual concessions: if workers surrendered wages or benefits, they would put the company in violation of minimum wage laws. Instead, management wanted them to sign a letter pleading for help — a crucial tool, supervisors said, for landing the contract needed to prevent the plant from shutting down. Senator William Proxmire was trying to snare that contract for a company in Wisconsin, the floor ladies explained. Who else to turn to but the rural community's most powerful resident and native son?

A few weeks later, Tennier announced that it had won the contract to make 94,000 sleeping bags.

Supervisor Elva Ruth Yeadon approached Sally Young,* extended pen and paper, and said, "Honey, sign this paper to thank Howard Baker for your job."

Young, who operates a sewing machine, turned to a mechanic working on some nearby equipment and replied, "I'm not gonna thank him. I don't like my job."

"You'd better thank him," the mechanic said dourly, "because without Howard Baker this place would have been gone."

Huntsville is not only Senator Howard Baker's home town but also, in 1981, the Southeast's leading per capita recipient of Pentagon prime contracts. On paper, the town got $24,079 for every man, woman and child within its limits. That's 15 percent more money per capita than was received by Lockheed-Georgia's home town of Marietta and three times more per capita than Newport News, Virginia.

The Pentagon spent $736,000 of those contract dollars in Huntsville in 1981 for body bags, the long, ghoulish sacks imprinted on American minds as a symbol of the Vietnam War. In 1981, 34,592 body bags were produced just off the Congressman Howard H. Baker Highway in a blue corrugated-metal building which sits directly over the top of an old radioactive waste dump — a legacy of Huntsville's previous military industry.

Huntsville exemplifies the costs, insecurity and webs of dependency caused by Department of Defense (DOD) penetration into all corners of economic activity. For all its military money, the town and the surrounding portion of East Tennessee's beautiful, damaged Cumberland Plateau remain poor. In 1981, Huntsville's per capita military contracts exceeded its per capita income of $5,191 four-and-a-half times over.

The people behind military contracting in Huntsville are two New York brothers. Their military apparel operations in Huntsville and two other rural East Tennessee communities — Clinton and Lenoir City — took in $17 million in 1981 defense contracts. Since the 1960s, Howard and Carle Thier have maneuvered their apparel business from town to town and region to region, setting up a family of interchangeable companies under different names and ostensibly different ownerships which the brothers and their associates insist have nothing to do with one another. In reality, those ventures — Tennier (called Helenwood Manufacturing until 1981), Lancer Clothing, Greenbrier Industries, Loudoun Industries, Downslope Industries, Eric Industries and Protective Apparel Corporation of America — have operated as a single entity, sharing personnel, contracts, office or plant space.

Maintaining the fictional lines helps the brothers fight unions, win preferences from DOD's contracting system and evade legal and moral responsibility to a skein of workers and communities. What makes all those communities inviting way stations to the Thiers is poverty — Scott County's chronic double-digit unemployment reached 22 percent in 1982. "You can't even get a job in a store around here," Sally Young says. "You know you got to like it or lump it."

The Thiers' operations represent the size and nature of most military contracting in the upper South, a region with relatively few big-ticket weapons producers like Lockheed or Tenneco. In 1981, about 550 companies received Tennessee's total of 2,734 DOD contracts worth more than $10,000. Most were infinitesimal if matched against all Pentagon spending: of those 2,734 awards, only 21 cost DOD more than $5 million. The more typical award in Tennessee is $12,000 to the Pickett County sheriff's department for "surveillance services" or $362,000 to Buring Food in Memphis for meat and fish.

As DOD commences the first weapons-buying binge in decades with enough magnitude to recast regional economies, the Southeast's military contractors remain largely subsets of traditional industries like textiles, food, tobacco and fuel. In 1981, clothing and textile products ranked as the second or third best-selling item to DOD for North Carolina ($106 million and 16 percent of all DOD procurements), Tennessee ($82 million, 16 percent), South Carolina ($69 million, 16 percent), Alabama ($80 million, 10 percent), Kentucky and Georgia.

Huntsville represents some important policy thrusts, too. Today, most public discourse over military production is monopolized by the "industrial preparedness" lobby bleating that DOD needs to reform its "adversarial" relationship with the "deteriorating defense industrial base." But all along the Pentagon has given contractors like the Thiers remarkable competitive advantages. And things are getting better, particularly with enlarged contracting preferences to small business and depressed rural and urban areas.

If recently created financial supports for small business presume that all small business is innovative, job-generating, loyal, clean, brave and trustworthy, then geographical targeting presumes that all money flowing to Labor Surplus Areas (LSAs), the government's designation for areas of high unemployment, means good things for workers and communities. Huntsville's body bag factory benefits from and belies those assumptions. In 1981, two-thirds of all the contract dollars flowing into Huntsville, $9.39 million, came as "total LSA and small business preferences." That means the company, trading on Scott County's poverty and recent congressional initiatives to target more of the defense budget to LSAs, could obtain "competitively bid" contracts even if it weren't the low bidder. Equally important, DOD seems to overlook the probability that Huntsville's military contractor may not be a small business. Effectively managed as one operation, the Thier brothers' three Tennessee companies employ far in excess of the 500-worker ceiling.

Adversarial relationship? Between 1977 and 1980, the federal government and the state of Tennessee gave the Thiers $79,434 in CETA funds to train workers for minimum-wage jobs. In 1981, their companies received $2.62 million in Government Furnished Material (GFM) via nine separate contracts. GFM comes in especially handy to the military garment industry, where material accounts for 65 to 85 percent of total contract cost, according to Howard and Carle Thier's comptroller, Steven Eisen. "If a contractor does not have to finance the cost of that material," Eisen reasons, "he's going to save a fortune in interest."

Huntsville also has some important things to say to America's fledgling peace movement and its most familiar critiques of American capitalism. As anybody worth his or her weight in peace movement pamphlets assumes, the DOD derives its power principally through multi-billion-dollar weapons programs, composing a warfare sector which profoundly influences, but functions external to, the larger economy. The "Sunbelt" — conjuring images of a land mass bristling with weapons facilities and militaristic fervor — hosts an ever-increasing majority of the benefits of that sector to the implied detriment of the peace-loving, decaying "Frostbelt." Military spending doesn't create many jobs, according to the traditional peace litany. Instead, the money goes to "capital-intensive industries;" the few jobs involved go to engineers and others in least desperate need of employment.

In fact, DOD derives a great deal of its power by buying into economies across the board. Strip miners, sheriff's departments, apparel companies, whole local economies receive small but vital props. While the Pentagon is attacking employment on a grand scale — particularly through its little-publicized automation subsidy programs — it undeniably creates jobs as well. And it does so in labor-intensive industries like clothing.

Ritualistic dismay over military porkbarreling, major weapons system ripoffs and Labor Department employment projections neither explains nor challenges the Southern military contracting system's nub, its intricate grass-roots impacts. It fails to examine what kinds of blue-collar jobs the Pentagon creates or how DOD shapes its contractors' relationships with workers and host communities. Howard Baker's home town is as good a place as any to ask those questions.

Since 1976, the Thiers' Huntsville operation has manufactured uniforms, tunics, flight jackets, tent liners and other standard items in DOD's annual $1 billion barrage of clothing and textile purchases. Tennier religiously follows the apparel industry's usual method of maintaining productivity and minimum-wage levels: consolidate two demanding jobs into one even more demanding job; dangle piecework rates at tantalizingly attainable levels; once the worker has mastered the operation, jerk production levels out of reach — and keep jerking. If (and only if) you're making production, you can take a smoking break — in groups of three around a red square painted on the floor.

The company complements its power to tantalize with a power to enlist workers as co-conspirators in such schemes as hiding a huge shipment of military mittens officially being made elsewhere or clamming up when DOD guests arrive. "They shafted the government a lot," says one sewing machine operator. "Rotten material, bad goods boxed on the bottom, good on the top. I don't see how what the government buys holds together." In 1981, shipments of mittens, high-altitude masks and sweat jackets all passed a DOD in-plant inspection but were returned when inspectors further down the line discovered what was on the bottom.

The company's biggest stick is its own impermanence, a quality it has emphasized to everyone. "I don't think they even own the sewing machines in Huntsville," says Lynn Tompkins, a lively, forthright woman who sewed 200 body bags a day during most of 1981. "They rent em. Two good semi-truckloads would get everything out." Delivering on that threat elsewhere — with DOD's cooperation — brought the Thier brothers to Huntsville.

Carle Thier has been making military apparel all his adult life. He says that, while still an industrial design student at New York University, he created a "unique" armored vest which attracted DOD's attention. Recruited by the military to develop his vest ideas, Thier soon went into the production side of military clothing. In 1966, he and a partner established Lancer Clothing Company in the small Hudson Valley town of Beacon, New York.

By 1973, Thier had taken control of the company and was looking for places to expand. He found one in southern West Virginia. Thier, his younger brother Howard and their cousin Martin Lane set up Greenbrier Industries in a venerable mill building at Rainelle, the biggest town in the poor coalfield end of Greenbrier County. Within four years, Greenbrier Industries was contracting $11.3 million of DOD work in West Virginia and at another plant in Knoxville.

When Carle Thier arrived in West Virginia, he set about ingratiating himself with the local elite. Greenbrier's landlord, a Rainelle insurance agent and state senator named Ralph Williams, says, "He appeared at the Lions Club and the Rotary around town and put on a big spiel that he was glad to be here and that he was really going to make this a thriving industrial metropolis in terms of sewing-machine type work."

The bonhomie didn't last long. "He'd get people in here for six weeks and let them go and hire somebody else," Wiliams continues. "I always had the feeling that they were enthralled with the philosophy of how they did things in New York."

Minimum wages, arbitrary hirings and firings, glue fumes, stifling heat and one particularly tyrannical floor supervisor all gnawed at the employees. So did the owners' superior airs. "Carle Thier looked at us down here that made money for him like we were a bunch of dumb hillbillies," says Nellie Tincher, a veteran sewing-machine operator at Greenbrier.

In April, 1977, Mrs. Tincher and other workers got the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU) to launch an organizing drive at Greenbrier. The company and its union-busting consultants, Long Island-based Consolidated Corporate Consultants, responded hamhandedly with threats and interrogations. Union organizers and supporters say local police harassed them.

The Thiers also recruited a more potent ally — the Pentagon. From the start of the union campaign, Carle Thier and Martin Lane peppered government contract officers with reports blaming "labor unrest" for Greenbrier's inability to meet delivery schedules. An administrative law judge later described all those reports as unsupported or untrue "windmills at which the company tilted." But the military believed in the windmills and consistently gave the company what it wanted. Contract officer Bernard Johns acknowledged that DOD conducted no "independent investigation" into Greenbrier's false claims about "labor unrest."

Greenbrier's chosen anti-union weapon was a $318,174 contract for women's coats. The Defense Personnel Support Center (DPSC), DOD's multibillion- dollar textile, food and medical goods contracting center in Philadelphia, awarded and administered that contract. In mid-July, after the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) ordered a representation election at Rainelle, Martin Lane wrote a letter to DPSC's Bernie Johns. Lane said the company was "exploring" the possibility of subcontracting the 34,360 women's coats in order to forestall "a production slowdown" linked to union activity. Two days after Lane wrote the letter, Greenbrier drew up that contract with Helenwood Manufacturing of Huntsville, Tennessee.

Helenwood, a brand-new company, had ostensibly been started by a burly 38-year-old lawyer named Jerome Eisenberg. Shuttling in from New York, Eisenberg cut a noticeable figure in rural Scott County. "He reminded me of what Raymond Burr used to look like in Perry Mason," says a legal colleague. "Really well-tailored, gold ring, but not ostentatious. To him, money talked." Eisenberg had grown up with the Thier brothers in Brooklyn; at the time he legally represented Carle Thier, Greenbrier Industries and Lancer Clothing.

"Like everybody else in the garment industry, these guys are fast on their feet," recalls Bob Love, an industrial development official who showed Eisenberg Scott County. "But hey, when you're in Scott County, you can't be too damn choosy about who you take in. Well, it's not just Scott. When you're in any isolated rural county and anybody has a way to create jobs, you'd better just swallow your pride and throw your feet way out to catch em."

For Eisenberg, Love says, "The big pitch was 'we've got labor and we'll give you a break on the building.'" Love's Scott County Industrial Development Board (IDB) arranged a juicy financing package, threw in $10,000 of sewing equipment and arranged "virtually rent-free" terms on the IDB's one and only radioactive industrial site.

The site's sorry history dated to 1969 and the advent of Nuclear Chemicals and Metals Corporation (NCMC). That company also received a sweet financing package from an earlier development group, the Great Scott Development Corporation. NCMC was the creature of E.R. Johnson Associates, whose founder arrived in Huntsville with a contract to deliver thorium metal to Oak Ridge 50 miles south of Huntsville. Also in tow as vice-presidents and stockholders were the recently resigned directors of the Atomic Energy Commission's (AEC) Materials Licensing Division and Nuclear Materials Safeguards Division. With these AEC heavyweights on board, NCMC emerged as the epitome of the reckless nuclear shop, flouting the law and common sense.

When NCMC began operation in 1970, a state pollution control officer warned that its waste pond's plastic liner, designed to prevent radioactive seepage, was "totally ineffective." It was never repaired. Thorium, used as a fuel for experimental reactors and nuclear submarines, has a long half-life and generates extremely toxic and biologically active daughter products. But in 1971, a state health inspector found that NCMC had taken hardly any smears, surveys or air samples to measure plant radioactivity during its first year of operation and concluded that the company "was not very interested in the safety aspects of the process."

In 1972, Johnson and company closed and abandoned the thoroughly contaminated plant and moved on to greener pastures. According to NCMC's former accountant, E.R. Johnson Associates now writes quality assurance and safety programs for clients like General Electric and Consolidated Edison.

It took six years to tidy up after NCMC. The building was eventually — and ineptly — washed down with water by the now-notorious TNS (Tennessee Nuclear Services), the subject of 1981 congressional investigations for its own atrocious health and safety conditions. And the waste pond's radioactive liquid was pumped into the New River, its sludge scraped and hauled off for burial in Oak Ridge in 1977.

None of the radioactive leavings deterred Jerry Eisenberg. In January, 1977, Eisenberg "extended a special thank you" to Howard Baker in the local paper, noting that without the senator's "cooperation this new business venture would not have been possible." Don Stansberry, a senior partner in the Baker law firm, helped arrange the terms of an IDB lease which Eisenberg signed in Baker's Huntsville law office.

By 1979 Helenwood Manufacturing had grown flush enough to build an extension over the top of the filled waste pond. During the next three years, a two-inch crack developed in the extension's slab floor. Contractors who laid a sewer line through the waste pond and sewing-machine operators who have worked on top of it suspect that it's still a health hazard.

The original NCMC part of the plant might be as well. Veteran nuclear workers say that it is impossible to eliminate radioactive materials from porous metal or concrete surfaces. Joseph Egan, a nuclear engineer and industry analyst who has reviewed the Tennessee Radiological Health Division NCMC file, observed glaring inconsistencies and "would not be at all surprised" to find radiation counts of two millirems per hour (the legal threshold for "restricted" areas) still in the plant.

From the perspective of the county's upper crust, Eisenberg did more than put the IDB's radioactive albatross back in use. He established a major source of employment with no threat to the prevailing parsimonious wage rate. And Eisenberg had a pipeline to federal money. At first that pipeline didn't stretch to the Pentagon. It cut through the coalfields to West Virginia and stopped. All Helenwood's government contracts in 1977 were subcontracts from Greenbrier. Greenbrier was financing Helenwood. And Bankers Trust of New York, Greenbrier's principal lender, had just made the Helenwood expansion easier by expanding the Thiers' credit line 70 percent and lending them an additional half-million dollars.

The pipeline to Rainelle also lent an extra element of potential illegality to the long-running NCMC fiasco. The Farmers Home administration (FmHA) paid for cleaning up NCMC's waste pond with a $21,000 grant. As that cleanup coincided with the Thiers' battle against ACTWU in West Virginia and the move to Tennessee, Scott County's boosters clearly violated the Rural Development Act. Like other federal programs, FmHA's development funds prohibit any use "calculated or likely to result in" a plant "transfer, " "close down" or "the increase in unemployment in the area of original location" (emphasis added). Those were precisely the three options the Thiers were exercising, under DOD's auspices, in West Virginia.

In late August, 1977, Greenbrier's Rainelle workers voted in the union despite the company's illegal pressures. Four days later, Thier and Lane started laying off workers. By November, they had dismissed 80 percent of the work force, telling them there weren't any contracts to work with. DPSC was reinforcing the idea that contracts were scarce, along with the Defense Contract Administration Service (DCAS), DOD's contract monitoring arm. During the Rainelle organizing campaign, DCAS had recommended against letting Greenbrier subcontract the women's coat order to Helenwood. Helenwood was already delinquent on four of its five government subcontracts. Nevertheless, DCAS soon reversed its "no award" recommendation just before the union election. Five days after the union vote, another DCAS survey, which rated Helenwood's production capacity and performance record "unsatisfactory," magically turned "satisfactory" — Greenbrier could transfer a $325,000 contract for more women's coats to Huntsville.

Nellie Tincher recalls that a Greenbrier supervisor told her that "The company was only going to work on small contracts and was not going to start on anything really big until we find out what the women are going to do" — i.e., stick with the union or acquiesce to the layoffs.

The contract shifting moved the Thiers' focus from West Virginia, the nation's most heavily unionized state to right-to-work Tennessee. Within the first months of Helenwood Manufacturing's operation, its plant manager heard about union cards circulating and illegally read workers the riot act. "He said if he even heard us mention the word 'union' we'd be out," remembers one of the initial employees.

But the Tennessee shift hadn't produced women's coats for Uncle Sam — just as DCAS originally warned. By January, 1978, four months and many delivery-date modifications after shipments were supposed to begin, Helenwood had yet to make its first delivery. Citing Greenbrier's "questionable integrity," DPSC contract officer Bernie Johns terminated one cost contract for default.

Two months later, Johns reinstated that contract at Helenwood. He later defended his reversal by describing "the government's urgent need" for those coats. In fact, the Thiers and Eisenberg supplied all the urgency because they had already cut all the coat material — $92,000 of Government Furnished Material — into parts.

All these maneuvers cost the Thiers the grand total of $2,375 for the termination and two other fines. But the Rainelle workers weren't being cowed out of their support for the union. And they weren't dropping the NLRB case they had filed against the company. Greenbrier gradually began rehiring workers, though the West Virginia plant was clearly now subordinate to the company's other operations.

In spring, 1979, management recognized the union. In September, 1979, Rainelle workers finally got their day in court when the NLRB pressed unfair labor practice charges against Greenbrier. In November, three weeks after the union received formal certification, Greenbrier announced that it was shutting down its Rainelle plant. In December, the company's trucks emptied its Rainelle building. "They moved out at night and on weekends," remembers one Greenbrier worker. "They had everything out in nothing flat."

A few weeks later, the labor law judge issued a rebuke-filled decision, ordering the folded company to rehire workers it had laid off in 1977 and award them back pay. The union and workers salvaged what they could — which turned out to be $50,000, or $403.23 per person.

Footloose again, the Thiers consolidated their assets in Clinton, Tennessee, the Anderson County seat, midway between Knoxville and Huntsville. Dealing with another desperate industrial development agency, the brothers jointly purchased a 70-yearold hosiery mill in downtown Clinton for another Lancer Clothing factory. That plant put the Knoxville and Beacon shops — both closed in 1979 — and part of the Rainelle operation under one roof. In 1980, with three-quarters of their contracts flowing to Clinton and the remainder to Huntsville, the Thiers' operation became the second-biggest military clothing and textile contractor in the United States.

In 1981, Lancer Clothing crushed an ACTWU organizing attempt at Clinton, employing familiar tactics. This time the company got out from under NLRB charges with a settlement of $ 10,000 paid to five workers fired for union activity. In Beacon, IBM is warehousing goods in Lancer's old New York factory. In Rainelle, a recently retired DOD clothing inspector named Larry Trainor has rallied residents to find financing for him to reopen the Greenbrier Industries building and get it back into military clothing production. Though capital-short, Trainor has promised ex-Greenbrier workers that they can have prayer breaks during production if he takes over. In Knoxville, 11 former employees of a Greenbrier division, Downslope Industries, are waiting for restitution five years after a court found that they had been illegally fired for standing up to a male supervisor who had threatened to rape several of them. Carle Thier and Jerry Eisenberg claim that Greenbrier and Downslope have ceased to exist and can only be held liable for one year of back pay. "We've got companies here that employ people who need jobs," Carle Thier says. "We perform a function for the United States government. We're no different from any other company with a good reputation in this business."

Carle Thier is part of an ascendant order. Sincere or insincere, in peace or at war, American policy makers have always gone through the motions of imposing some moral, financial and regulatory controls on those who profit from war. But Ronald Reagan's hacks explicitly tout their military budget as an instrument for making America's "business climate" more "competitive." Caspar Weinberger's Deputy Secretary Frank Carlucci has made OSD (Office of the Secretary of Defense) a more overt opponent of environmental and health-and-safety regulation than any peacetime predecessor. DOD industrial policy means profit policy, guaranteed return on investments, outright loans, multi-year buys. The few bureaucrats charged with keeping DOD's nose clean are losing ground.

The Thiers are neither exceptionally bad apples nor a bitter foretaste of DOD's new supply-side look. The human, environmental and financial costs involved in their story echo through many other areas of military production. Those costs are often invisible, even to people involved in military production.

Visibility has to do with information control, the kind of information sources that went into this inquiry — contracts, pre-award surveys, correspondence regarding place of performance, delivery schedules and materials. All the hidden paperwork that symbolizes the layers of insulation DOD provides contractors needs to be aired out. Sanitized forms of that paperwork can be obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, a grinding process that puts contracting agencies in the driver's seat and citizens in the supplicant position. That's backwards. Lancer and Tennier workers should have the right to complete information about their shop — like whether management is juggling contracts to prepare for another move.

However, gaining control of information can't fully redress the galloping insecurity associated with military production. The power that contractors wield won't bend or break just because it is identified as the problem. Contractors like the Thiers don't have to get DOD's carte blanche to roam the country in search of the coziest combination of high unemployment, desperate industrial development authorities and wired-up political connections. DOD could institute contracting procedures that instill more security and incur fewer costs for workers and communities.

Even a contracting system that paid attention to the first line of defense wouldn't alter DOD's massive penetration of our economic system. Achieving real security in places like Huntsville, Tennessee, means making fundamentally democratic changes in who controls the economy as well as in what it produces.

Tags

Tom Schlesinger

Tom Schlesinger, principal author of Our Own Worst Enemy: The Impact of Military Production on the Upper South, is the director of the Southern Finance Project, a research effort sponsored by the Institute for Southern Studies. (1986)

Tom Schlesinger is a free-lance writer living in Tennessee. The Fund for Investigative Journalism supported research for this article. (1982)