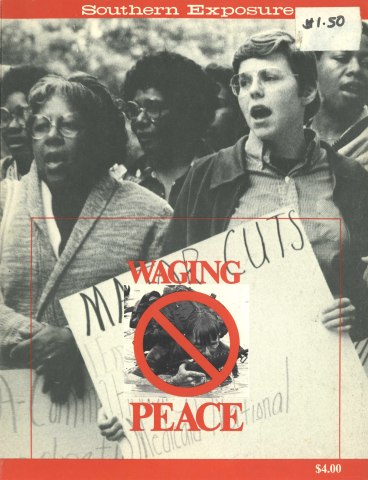

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

In 1981, three Southern Organizations came together to cosponsor an organizing effort, the Southeast Project on Human Needs and Peace. The three groups are the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Southern Exposure, War Resisters League-Southeast; and the Southern Organizing Committee for Economic and Social Justice (SOC). After months of planning, the project began in early 1982; I was selected as the full-time field worker.

All our organizations were already involved in work for world peace. The first issue of Southern Exposure, published in 1973, focused on militarism in the southern United States. War Resisters League is a national pacifist organization which has built resistance to every war since World War II; it opened a Southeast regional office in 1977. The Southern Organizing Committee, headquartered in Birmingham, Alabama, is a multi-issue, multi-racial network formed in 1975, growing out of earlier civil-rights organizations. It works to join the issues of economic injustice, racism and war and, since 1978, has made it a priority to link up people organizing for economic survival with those working for world peace — promoting such ideas as Jobs with Peace elections in the South and bringing information on militarism to people previously unreached by traditional peace organizations.

The long-range objective of the Southeast Project is to help plant seeds for the movement the South must produce: one joining efforts of black and white, labor, religious groups, tenant groups, feminists, peace organizations, civil-rights groups — a movement to change the direction of our nation. But much groundwork must be done before that movement can develop. We started with the assumption that this country's priorities will change when people whose needs are not being met by present priorities come together and say "No."

"Human needs" is a widely used phrase now, almost a cliché, but human needs has to do with flesh-and-blood people who are hungry, jobless, sick and uneducated in this land of plenty. For millions, it has to do with that basic requirement for human life: a place to live. In this, the richest country in the world, decent housing is not available at prices people can afford, and even that which is available is now threatened.

All across the South, people whose right to shelter is endangered are indeed saying "No." They are saying: "We will not give up our right to live." Through the years, the tenant movement has produced some of the strongest fighters in this country. They have rocked the foundations of power many times before, and they are organizing to do it again.

We think it's time to move beyond the rhetoric of support for human needs and put resources at the disposal of these fighters. The Southeast Project on Human Needs and Peace decided that its first priority should be to provide assistance to the housing movement that is growing again in the South.

SELINA FORD heads one of the 1.2 million public housing households in the U.S. She lives in a three-bedroom apartment with her four daughters in the St. Thomas housing project in New Orleans, near the Mississippi River and a stone's throw from the site of the 1984 World's Fair.

Since February, her rent and utilities have cost her up to 104 percent of her income. Housing costs for Selina are out of control. On an income of $234 per month, she paid her landlord — the Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO) — $167 for utilities in June and $209 in July, in addition to $35 per month for rent.

When she was billed for July utilities in August, Ford realized the situation had become impossible. She and her neighbors had already occupied the headquarters of the HANO in June and July to protest utility charges and lack of maintenance. In August, they began a rent strike.

Barbara Jackson, president of the St. Thomas Residents Council, said the tenants were forced to strike. "Sometimes when you can't get justice, action speaks louder than words," she said.

More than 450 of the approximately 1,300 families in St. Thomas joined the rent strike. By September, they had deposited more than $90,000 in an escrow account, giving them an added sense of their power to control utility bills and repairs. The New Orleans Citywide Residents Council is lending assistance.

The Tenants also filed individual grievances en masse. St. Thomas manager Frances Butler says the authority management has decided not to hear the grievances. Grievance procedures require a hearing within a reasonable time.

In September, HANO initiated legal proceedings to evict the striking tenants. The St. Thomas Residents Council and the Citywide Residents Council responded with a class-action lawsuit. The suit charges HANO with violations of regulations set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the federal agency which administers low- and moderate-income urban housing programs.

Utility costs are supposed to be included in rent paid by public housing tenants. When the New Orleans rent strike began, the law specifically limited to 10 percent the number of tenants in a housing complex who could be charged extra for "excess" utility consumption. During the 1982 summer, HANO was assessing excess charges against 90 percent of public-housing residents. Since the strike began, HUD has published new rules giving housing authorities practically a free hand in setting excess utility charges.

The St. Thomas suit also accuses HANO of failing to establish the grievance and appeals process required by law. And in their grievances the tenants charge poor maintenance and conditions hazardous to health and safety in their apartments and on the grounds.

There have been some changes since the rent strike began. Maintenance employees are working feverishly to repair the hazardous conditions. Tenants have negotiated an unwritten agreement with HANO: strikers will not be evicted if they return the escrowed rents to HANO when repairs to a tenant's apartment are completed; tenants will keep utility charges in escrow until this issue is resolved in court or by agreement.

This agreement is tentative and could evaporate at any time. Moreover, HUD, now standing in the background, is likely to use its power over HANO to try to break the strike, as it has done in countless similar situations.

Selina Ford and the St. Thomas tenants aren't alone. The conditions against which they are struggling are duplicated across the South and the nation. The stated objective of the Reagan administration is to eliminate public housing entirely. Private landlords can house the poor better, Reagan says.

The long-range objective of the present national administration is to sell public housing to private real estate developers (who charge exorbitant rent and usually won't even rent at all to large, especially black, families), or demolish it to make room for commercial investments. HUD is currently studying the best way to demolish 65,000 public housing apartments by the end of 1983.

In the meantime, conditions for those living in public housing are a far cry from what was envisioned when St. Thomas was built in 1939, the first public-housing project in New Orleans and one of the first in the country. Two years earlier, Congress had passed the Wagner-Taft Act, which authorized the federal government to provide a "decent home at prices the poor can afford to pay."

Between 1937 and the 1960s, public-housing practices moved away from the original intent. Rents went up, and maintenance deteriorated. Then a strong national tenant organizing drive grew out of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1969, Congress enacted an amendment to the Housing Act setting tenants' rent at 25 percent of adjusted gross annual income. Rehabilitation work started in many projects in the early '70s.

The current attack on public housing began under President Nixon and continued under subsequent administrations. Funds to build new public housing were decreased, then eliminated, although waiting lists grew. Operating funds were gradually decreased, eliminating maintenance. A new federal policy forced housing authorities to fill vacancies with higher-income tenants, while the very poor remained on waiting lists, paying high rents for slum housing. And, in 1981, Congress raised the percentage of adjusted income tenants can be charged as rent. Under new regulations, effective in October, 1982, current tenants must pay an extra one percent per year until their rent reaches 30 percent of income; new tenants must pay 30 percent immediately.

Like many public housing communities, St. Thomas is in dire need of rehabilitation, but its structural elements — roofing, walls, foundation — are sound. And it is a project of beautiful and spacious courtyards and alley ways. Balconies overlooking courtyards could be enlivened with greenery and flowers with a minimum investment, but instead conditions are only worsening: tree roots have crept into sewer lines, plumbing is rotting, stairways have worn, ceilings have fallen, floor tiles have deteriorated.

Housing authorities are unable to do rehabilitation unless they use sparse local funds; they are struggling just to keep their doors open. Public housing operating funds have already been cut to the bone. President Reagan now proposes to cut them in 1983 to 65 percent of what it costs to maintain current service levels, and to 25 percent of need in 1984. (That, according to tenant leaders, will only provide staff to administer a voucher program — Reagan's plan to replace public housing with subsidies to private landlords.)

Robert Chadbourne, HANO's director of research and development, testified before Congress in early 1982, urging lawmakers not to destroy public housing, and his job.

"Public housing," said Chadbourne, "will be seriously damaged by a 15 percent cut in subsidy and could be destroyed by a 30 percent cut. The repercussions of this tragedy upon the total community, especially in large cities, would be devastating, affecting the economy, the safety, the very lives of tens of millions of people who have previously felt insulated and aloof from the world of the projects, but who would have involuntarily thrust upon them the realization that they too are a part of the delicate balance."

Several tenants see a link between escalating rents and utilities in St. Thomas and the desire of businesspeople to purchase this and other central city housing projects. St. Thomas is very close to the 1984 World's Fair site. Another federally subsidized apartment building in New Orleans was emptied during the St. Thomas rent strike to make room for World's Fair tourists. In some cities (for example, Alexandria, Virginia), housing projects are already being sold to private developers.

Tenant leaders in many communities, like New Orleans, are fighting back and developing their power. On May 5, 1982, 20,000 public housing tenants marched on Congress and HUD to demand an end to demolition and sale of public housing. One result was that Congress defeated a proposal to order housing authorities to count food stamps as earned income in determining rent. Such a change would have increased Selina Ford's rent by $60 a month.

In the 1960s, public housing tenants sharpened their skills and organized to meet a similar crisis. In the process they developed strategies and power that removed the absolute right of landlords to evict — not only for public housing tenants, but for all tenants. The struggles of the '60s against a racist, anti-poor government bureaucracy led to regulations and laws governing security deposits, retaliatory evictions and leases that protect tenants in every major city.

While that earlier movement for humane housing laws made immense changes, it stopped short of fully integrating and institutionalizing tenant influence and power in state legislatures, Congress, city halls and federal agencies. The goals of the current movement are tenant participation and control at all levels of government.

Tenants are also fighting at the local level against mismanagement. One weapon Reagan and his supporters use in attacking public housing is the charge that the program has created a bureaucracy that is inefficient, wasteful and fraudulent. There is validity to this charge. Written operating procedures exist but frequently are not followed. Waste and inefficiency are apparent. Services fall through the cracks. No one knows all this better than the tenants, and the answer is strong tenant organization — not the destruction of public housing.

Solving problems in public housing makes leaders of people who never intended to play this role. Barbara Jackson describes what happened to her, starting four years ago:

When I first moved to St. Thomas, I knew there were problems. So I started attending meetings and got involved. That's when I got nominated for president. It was a hard struggle, because I didn't have an active board. I was trying to feel my way forward to see what my duties were. At first, I had the misconception that it was like membership in a social club. But I found that people didn't have heaters, stoves, had holes in their ceilings. As time progressed, I became more familiar with what we had to do.

As Ms. Jackson and other St. Thomas leaders became familiar with the work of tenant organizations, they developed a plan to continue and expand tenants' control over their own lives. What they are up against was summarized by Cushing Dolbeare, president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, when she testified before congressional committees this year against the massive attack on public housing. She said low-income housing programs took the largest budget cut of any federal program in Fiscal Year 1982 and apparently will be the hardest hit again in 1983. She added: "Indeed, the 1983 increase in the military budget could be funded out of the 1982 and 1983 low-income housing cuts alone."

THE SHIFT of housing and social program funds to the nation's military budget has now become very clear. Jesse Gray, activist in black liberation and housing movements since the '40s and now chair of the National Tenants Organization, addressed 300 tenants at a Memorial Day rally in Memphis in May, 1982. He said:

Reagan is putting public housing funds into the generals' hands to buy more missiles to aim at the Soviet Union. We are told this is necessary to stop the Soviets. The Soviets have been coming since I was a boy, and they haven't got here yet. Tenants are not afraid of the Soviets coming. We are afraid of Reagan coming.

If the generals push the nuclear buttons, our long struggle to be free will be over. Tenants, we can't eat bullets or put the warfare chemicals over the children's cereal as a milk substitute. The cost of three of those new M-l tanks would go a long way toward rehabilitating public housing in Memphis.

Tenant leaders point out that shifting funds from the military back to housing could provide jobs for the jobless. According to economist Marion Anderson, one billion dollars spent to build MX missiles will create 17,000 jobs. That amount spent to build new public housing could provide 62,000 jobs. Many tenants are becoming convinced that public housing will survive only if the nation's priorities are changed — from guns to housing, to nutrition, health care, education.

We in the Southeast Project on Human Needs and Peace see the developing tenant organizations in the South as a basic component in a movement that can change those priorities. We are assisting this tenant movement by providing technical help, leadership training and information that facilitates organizing. Thus far, we are working with housing movement leadership in five Southern cities: Birmingham, Charleston, Durham, Memphis and New Orleans. Each of these cities has a tenant organization in nearly every public housing project. We conduct small-group workshops and sponsored a tour by Jesse Gray to give tenants the benefit of his 40 years of organizing experience. We see our role as staying on tap when tenants need and request services — and not on top of their movement.

At the same time, we are encouraging peace organizations to support the life-and-death struggle of tenants to save their homes. Such support work presents many difficulties. Most tenant organizations in the South are predominantly black; most peace organizations are predominantly white. In addition, there are sharp class differences. All of us tend to develop our own styles of organizing, and it is too easy — whether we intend to or not — to try to impose our style on others whose way of working may be quite different. Tenant groups want and desperately need support, but like every significant social movement, they want and need support that does not carry with it domination.

One stumbling block to such work is the tendency of many whites, especially the middle class, to want to lead any effort in which they are involved. What they must do first if they are to support the tenant movement is to get rid of their delusions of superiority and their contempt for the skill levels and leadership potential of blacks and poor white people. The role of non-tenants is not to organize in public-housing neighborhoods but to help mobilize massive movements in the larger community to compel the federal government — and local government and private industry — to begin funding housing and other human needs. There is a tremendous educational job to be done in every community in America to show people how they have been fooled by racism into thinking that public housing is only for blacks, at the expense of whites. For instance, whites need to learn that more whites than blacks have housing needs that could be met by a decent housing program.

The key is for all of us to realize that a society that refuses to meet the basic human need of shelter sets its course toward destruction and death; conversely, a society that commits itself to meet this need turns toward life. And when it makes that turn, it will take a giant step toward rejecting the idea that problems can be solved by militarism and war. Tenants, over the years, have realized that this turn will be taken when movements from the grassroots force it to happen. The people have the power. That power will prevail over utilities, HUD, bad publicity, outside domination and the Pentagon.

"Whites seem to come out to protest when it's about the war. What we want to know is where are you when black people are in a life-and-death struggle to survive at home." — Moe Rapier, spokesperson for the Black Workers Coalition in Louisville, 1972

Tags

Pat Bryant

Pat Bryant is a writer, community organizer, and director of Gulf Coast Tenant Organization, which operates in poor African American communities in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. He is a board member of SOC and the Institute for Southern Studies in Durham, NC.

Pat Bryant is an editor of Southern Exposure and field organizer for the Southeast Project on Human Needs and Peace. (1982)