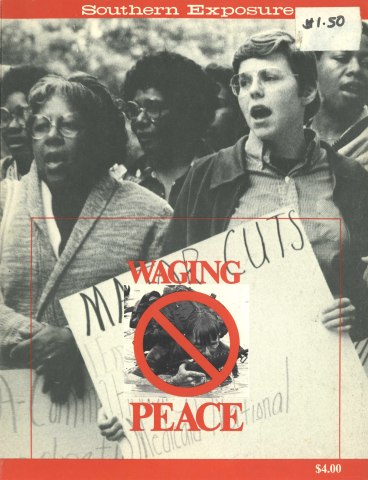

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

On June 12,1982, when more than 750,000 people gathered in New York to march for peace, the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom was well represented. On that same day, an editorial entitled "U.N. March" appeared in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, repeating the Virginia newspaper's position opposing a freeze on nuclear weapons and condemning many of the organizations responsible for the nuclear freeze movement and the march that day. The organizations were described as the same groups which "only a decade ago had struggled to help enthrone the bloody regimes that have given the world the Boat People, the Cambodian holocaust and kindred barbarians." The editor wondered why these groups hadn't "dissolved . . . in shame and guilt." Included in the list of peace groups was the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF).

That same week, the Wall Street Journal carried a column which questioned the motives of the architects of the nuclear freeze movement, given the "congeniality" of their views with those of the Soviet Union. Again, WILPF was named.

WILPF women have been marching, lobbying, leafletting, letter-writing, educating, fundraising, witnessing and organizing for peace since 1915. That WILPF should come under attack from a mouthpiece of American conservatism like the Times-Dispatch and that WILPF should be linked to the "communist conspiracy" is hardly news. The oldest peace organization in the United States, WILPF has weathered these kinds of charges since its inception.

WILPF's most famous and revered founding mother was Jane Addams. It was her view that "peace is not merely the absence of war, but the nurture of human life," that social, political and economic justice and the elimination of discrimination based on race, sex, creed and class are essential to the establishment of a peaceful world. Addams was certain that, as "nurturers of human life," women should assume special responsibility in the quest for peace. It was Addams who presided at the Women's Peace Congress at The Hague in 1915, when a thousand women from 12 neutral and warring nations called for an end to World War I, general disarmament by international agreement and an end to all discrimination. Thus was laid the foundation for WILPF, a union of women for whom PEACE and FREEDOM are indivisible, one possible only with the other.

Addams, who had been called a saint for her work as a social reformer, who had been proclaimed America's most admired and beloved woman, rapidly fell from grace with the American press and people when she began promoting her pacifist position. She was branded a traitor for helping to organize WILPF and was called a bolshevik and "the most dangerous woman in America" when she denounced the U.S. entry into World War I. The current-day charges have a curious echo.

Her delicate, fragile appearance and her quiet, almost quivering voice mask her strength and perseverance. Called a "pillar" of the organization, Marii Hasegawa eloquently embodies what WILPF is all about. A member since 1946, she was elected president of the United States section of WILPF in 1971 and was one of eight women from six countries who toured Vietnam in 1973 to determine the true extent of war damage. Her stature in the national organization is enhanced by her continuing activism on the local level. It is rare not to find her at each demonstration, meeting, program or fundraiser sponsored by the Richmond, Virginia, branch of WILPF and the various coalitions to which it belongs.

An American of Japanese descent, Hasegawa was one of the victims of the massive internment of Japanese-Americans at the outbreak of World War II. Despite a 13-month internment and forced relocation to the Midwest, she supported the war, believing that the atrocities of nazism, fascism and imperialism could be combated only with military action. It was the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that moved her to understand that a military solution was really no solution at all. That new understanding led her to WILPF.

"I looked for a group," Hasegawa explains, "an umbrella organization in which it was possible to do many things under one banner, to help me look to the end of all this war and injustice."

Then living in Burlington County, New Jersey, Hasegawa in her early thirties found herself in a group composed almost entirely of white women in their sixties, women who had maintained their belief in nonviolence throughout America's most popular war. She recalls that everything was done in a very ladylike fashion, the style tending towards white gloves and afternoon teas, a fascinating portrait of women whose ideas were quite radical.

"Because I was from an ethnic minority, the Burlington County WILPF branch was now able to live what WILPF was. I experienced no feeling of outsidedness. I was the beginning of our really becoming a multiethnic organization. I like to talk in multiethnic terms, rather than multiracial . . . it is so hard to categorize people," says Hasegawa.

"Black women joined the group after I came. At first the older women had a rather patronizing relationship with the black community. But they were generous in supporting the local community center, and gradually they changed and got caught up in the ferment of desegregation."

The age gap that Hasegawa experienced is not unlike what young women joining WILPF today can find. She explains that WILPF seems to "skip generations," because somehow children need to be different from their parents. The connections made between young women and older WILPF members are invaluable. Little else works better to soften the arrogance of youthful idealism than to be in the presence of people who have been involved in social change longer than one has been alive. And the challenge of youthful idealism helps to maintain that spirit in those who otherwise might grow weary of the struggle.

When Hasegawa and her family moved to Richmond in 1965, the national office asked her to establish a WILPF branch in her new community. A fledgling organization called the Richmond Committee for Peace Education had formed in 1964 to protest the war in Vietnam. It was a biracial group, given to frequent meetings and educational forums.

There Hasegawa met Phyllis Conklin, one of the organizers of the committee, who came to the peace movement as a natural outgrowth of her Quaker faith. The bonding of these two remarkable women led to the formation of the Richmond branch of WILPF.

It didn't happen overnight. The Richmond "Red Squad" — local police assigned to monitor anti-war activities — began taking pictures and otherwise intimidating local peace activists; their work quickly chilled WILPF's early efforts to stimulate dissent. When Hasegawa and Conklin began recruiting women to form a local branch, they found that many shied away, claiming that WILPF was "too subversive."

It took nearly two years, but their efforts started gaining supporters in the summer of 1967, and WILPF quickly became a Richmond contact for anti-war and civil-rights initiatives. WILPF was active in the Richmond Coalition for Peace, Freedom and Justice, and until 1972 held weekly vigils at the Army Induction Center. WILPF promoted the lettuce, grape and Gallo boycotts on behalf of the United Farm Workers and was represented in the campaign for fair housing in Richmond.

After years of extensive activity at the height of the Civil Rights Movement and during the Vietnam War, membership in the Richmond branch of WILPF began to dwindle. A period of quiet followed during which the two friends steadfastly maintained the branch through participation in various coalitions and sponsorship of study groups on such topics as revolution, ethnicity and race. Today membership is on the rise and the branch is once again engaged in labor-intensive peacemaking activity.

At age 62, what compels Phyllis Conklin to spend a dinner hour speaking about the arms race and the freeze campaign to a rural Kiwanis club or to be at the site of a local fair at 8:00 on a Saturday morning setting up the freeze campaign booth? What moves Marii Hasegawa to host envelope-stuffing parties at her home or to join the planning committee of a local conference on racism? Both admit to building their lives and forming their friendships around the causes they espouse.

Conklin obviously enjoys the clash of ideas: "I relish each new opportunity to talk with people." Hasegawa, perhaps quieter in her determination, quotes Jane Addams, who wouldn't "quit before the final try."

Asked whether she would characterize WILPF, despite its members' outward serenity, as a militant organization, Conklin says, "WILPF women are occasionally willing to be arrested; our opposition to war is always nonviolent and always vigorous. But militant is a word barbed with messages. WILPF women are reasoned, calm, determined, sometimes brave. Not militant, but not moderate."

Tags

Sheila Crowley

Sheila Crowley is director of the Women's Issues Program of the Richmond YWCA. (1982)