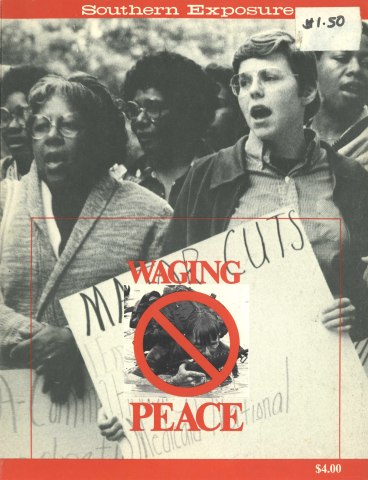

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

Growing up in a Southern military town, I found that things like war, killing and violence were constant, pervasive elements of the local atmosphere — like the stench of Sulphur in a paper mill town. I turned 18 in 1968. The assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy and the Tet offensive all happened the year I graduated from high school.

The reality of the Vietnam War was a somewhat unquestioned way of life in my home town. At least, I didn't know what questions to ask. When the guys from my graduating class started getting drafted, the war became more personal for me.

Then I began to meet marines — my age — who had come back from "that place." Their stories, told with a facade of machismo that barely concealed their own pain and confusion, made the evening news — with its shots of fleeing mothers, charred bodies, napalmed villages and body bags — all too real. The transition from Southern school girl looking for a husband to anti-war activist is far too complicated to explain here, but those hometown experiences steered me in the direction of the anti-war movement.

The more deeply I got involved in peace work, the more I began to question the connection between military violence on a global level and the violence against women that had been so prevalent in my home town. As in any military town, weekend rapes were commonplace, girls and women who happened to go into the "wrong" part of town were harassed, and there were always the hushed, half-told stories of wives and girlfriends being beaten, raped, sometimes even killed.

When I stumbled upon feminist essays and began to discuss feminist theory in the early '70s, the connections became more apparent. The further I looked, the more I understood that my political actions had to be rooted in my experiences as a woman.

After the war in Vietnam was supposedly over — at least the troops were home — I began to devote all my energy to organizing around women's issues. With my work in the anti-rape movement, I gained a more sophisticated understanding of the connections between violence against women and the violence of war, racism and exploitation: the connections of power, domination and greed.

I became very angry during those years. It is hard to look at how oppression intersects with your life and not begin to hate. But at about this point in my personal and political evolution, I began to believe that the theories of feminism and nonviolence were somehow, at their root, connected. It wasn't until later, when I was once again involved in the peace movement, that the connection became a motivating force for me.

With most peace groups — the left in general for that matter — feminism has remained a peripheral issue. For years now, women in these groups have met to discuss common concerns — from the fundamental, like being taken seriously, to the practical, like having an active role in organizational development and leadership. Our concerns have been brought back to the larger groups, demands made and incorporated, and then it was back to business as usual. While over the past few years women may have been more visible, may have gained more influence, our organizations, on the whole, remain limited in terms of feminist influence and action. They may be more sensitive to women's issues, but a comprehensive feminist understanding remains absent.

In a few cases, though, feminism has actually changed the group's politics, analysis and operation. The War Resisters League (WRL) is a specific example. For over five years now, WRL's Feminism and Nonviolence program has integrated the issues of women's oppression and militarism in its organizing and educational work. Although the program is independently identified, its philosophy is integrated throughout the organization.

When I came to work for WRL's Southeastern office, part of my work was to coordinate the Feminism and Nonviolence program. We brought together a mixed group — men and women — who wanted to do antimilitarist work from an expressly feminist perspective. We had only been meeting for a few months when one of the New York WRL staff members told me about an all-women's group that was forming to demonstrate at the Pentagon on November 16, 1980.

I remember her explaining the four stages the demonstration would take: mourning, rage, empowerment, defiance. It just didn't register. What was attractive to me about the Women's Pentagon Action (WPA) was that it was organized by and for women — peace activists, feminists, environmentalists, lesbians — to come together from all our different backgrounds to find each other and to go further together as women against the military establishment.

The idea seemed radical, scary, marvelous. Even though I had the personal satisfaction of working in an integrated feminist organization, it produced a sort of schizophrenia to be identified as a radical feminist and yet have most of my political work happening in groups where feminism is suspect at best, and at worst considered divisive. So the opportunity to work with a group of women whose sole purpose was to confront the Pentagon — the bastion of male-supremist militarism — with feminist nonviolence was exhilarating, hilirating.

Off our backs described the Women's Pentagon Action as "an exciting cross-fertilization of ideas from different movements: the tactic of civil disobedience from the black civil-rights . . . and anti-war movements; guerrilla theater, used by the Yippies and 1960s feminists; collective process and decentralized organization, developed by feminists and anarchists; a commitment to working with women and discussions about the politics of lesbianism, originating with the feminist and lesbian-feminist movements; and affinity groups, associated with the antinuclear movement."

For some women, WPA was their first involvement, at least on an active level, with feminists. For others, it was their first contact with organized lesbian-feminists. For many lesbians, it was their first time working in a mixed group. And for still other women, it was their first time in any sort of organized demonstration.

This coalescing of different kinds of women through WPA was one of its most significant features. It's not only the unprecedented nature of who came together, but the ways we've found to stay together and work with unity in the midst of our diversity. One promising legacy of WPA is the bonding achieved through our use of affinity groups.

Affinity groups, most recently popularized in the massive nuclear power protests, are clusters of perhaps a dozen people who train together to participate in civil disobedience. Those in each group who have decided that they are willing to be arrested, tried and perhaps convicted for "illegally" scaling a fence or blocking an entrance make deep commitments to each other: they will act as one nonviolent unit, each totally dependent on and responsible for the others. Those who are not willing or able to get arrested serve as support; they witness the civil disobedience and follow their friends through the legal procedures. The support group also contacts lawyers, families, doctors or clergy if necessary. Affinity groups help to protect against provocateurs within the action and to ensure that no one involved in the demonstration is left alone.

Having been a part of so many different social change movements in the past 10 years, I have often felt my feminist self — the core of my politics — is the most vulnerable, the easiest lost. But through the bonding of an all-women's action, feminism became my center, the spirit that guided my action and that of thousands of other women who participated. WPA heralded the emergence of a new feminist, anti-militarist movement.

The understanding that brought us together is fundamental to the theory of total nonviolent revolution: sexism, racism and militarism are all part of the same problem. And whether the exploitation, destruction or annihilation is of women's bodies or minds, or of entire cultures, the military mindset that dictates the use of force to achieve a goal must be eradicated. I have believed for a long time that if feminist theory is to become a reality, it can only come through restructuring of our entire society — nonviolent feminist revolution. The Women's Pentagon Action provided a concrete beginning strategy for making that belief become reality.

That the personal is political is a cornerstone of feminism. During my participation in WPA, what a friend called "the unity of politics and emotion" was for me the most empowering merger. My belief that war is wrong, that violence as a way to get and maintain power is wrong, and that war is waged daily on people who are considered "other" by the powerful is not separate from my grief, my emotional reaction to this violence and injustice. By dramatizing stages of our emotions in the Pentagon demonstration — mourning, rage, empowerment and defiance — and making that our political statement, the WPA brought my entire being into focus against what seems such an omnipotent power.

When I walked silently past all those gravemarkers in Arlington Cemetery, when with thousands of women we encircled the Pentagon, a flood of emotion caught me and I realized for the first time in my life what it means to merge the personal and political in direct action.

The first phase of our action was mourning: we were mourning for real people. The second stage of the Women's Pentagon Action was rage. Walking in silence from the gravesites to the Pentagon, you cannot help but make the connection. Here the decisions are made to send young soldiers to kill or be killed, sometimes both. If you mourn for each gravemarker and the suffering it represents, you must be enraged. If you are a woman whose culture accepts only your grief, rage becomes an emotion of exquisite release.

Release equals freedom; freedom equals power. Empowerment is the Women's Pentagon Action's third stage. When you consider that to the Pentagon power is measured in megatons, the personal energy of one woman — or thousands — may seem infinitesimal. For the women who surround the building in a human circle to block the entrance and exit of Pentagon officials, the energy is absorbed, the power is personal, nonviolent.

Once you understand that the power of the Pentagon lies not in people or ideas, but in weapons, that its principles are based on dominance rather than justice, that it feeds on conflict and starves in peace, then you can defy it. You can ridicule it. You can paralyze it, if only momentarily. In that moment you come to realize that the Pentagon and all it represents are not omnipotent.

During the final stage — defiance — WPA demonstrators wove a barrier of ribbons and strings and strips of cloth across the Pentagon's entrances. The guards cut, we wove. We were faster. The guards brought hedge clippers in order to cut more, faster. More women moved in with more strings and ribbons. Weaving, cutting, weaving, cutting. It went on for hours, stopping only when the Pentagon guards had arrested all the WPA weavers.

There have been two Women's Pentagon Actions — in 1980 and 1981. There will not be another in 1982. Although the '81 demonstration was more than twice as large as the first, our purpose in organizing and participating in them was not to create ever-larger annual demonstrations. Our purpose was — and is — to give women the opportunity to learn from each other, to find our own strengths, to rely on our own wits and creativity, to find our own ways of challenging the violence in our daily lives and the violence of the Pentagon which is its counterpart.

Our task is to take that understanding back to our communities, to our organizations; to help them understand that our power does not derive from the size or quantity of our weapons but from the quality of our spirit and the depth of our concern for each other.

Although WPA will not return to the Pentagon this year, it will not cease to exist. The women in WPA-South will continue to work together. One of the most serious internal issues we faced has yet to be remedied: both Pentagon actions were almost totally white and predominantly middle class.

We live in a society segregated by race and class. We recognize this and detest it; yet breaking down the barriers built over generations of hate and mistrust is almost as formidable a task as challenging the Pentagon.

WPA-South has begun the task by setting simultaneous goals for ourselves: first, to reach personal understanding about what WPA labeled in its Unity Statement "the pathology of racism," to educate ourselves about its history and the reality of living with racism for our sisters of color. The second step is to act: we are reaching out to women of color in our communities to offer our resources, time, energy and commitment to organize around their issues and concerns. In the near future, we hope to set up a multi-ethnic community dialogue for women to educate each other to break down the barriers on all fronts that keep women from working together. We are all headed in the same direction; we just have to find each other.

Another issue that arises again and again is that of separatism. All-women actions are somehow seen as a threat to mixed organizations; a diversion of people and energy during a critical period in the peace movement's history. What the critics don't seem to understand is that many women left the peace movement, not to destroy the movement, but because the groups they were part of did not consider sexism as serious as other internal issues. Nor did the peace movement understand the strength to be derived from feminist influence.

WPA created a place for women to band together for the sake of our personal and political power. For some, WPA or other all-women groups are the only place they feel comfortable doing political work. Others, like myself, feel centered in WPA but also work with mixed groups. We come to these groups energized and motivated by our WPA experiences and strengthened to struggle with injustice outside our movements and within.

Tags

Dannia Southerland

Liz Wheaton

Liz Wheaton is a staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies. She was formerly on the staff of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Southern Women’s Rights Project. (1981)