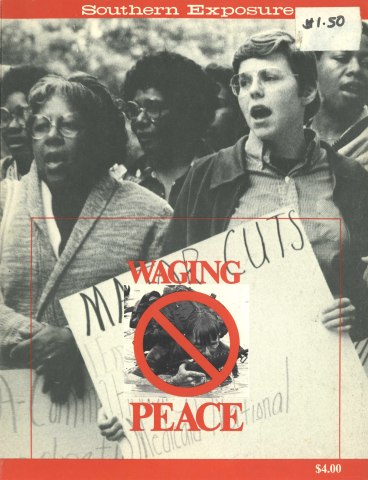

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

To improve national and international security, the United States and the Soviet Union should stop the nuclear arms race. Specifically, they should adopt a mutual freeze on the testing, production and deployment of nuclear weapons and of missiles and new aircraft designed primarily to deliver nuclear weapons. This is an essential, verifiable first step toward lessening the risk of nuclear war and reducing the nuclear arsenals. — from the "Call to Halt the Nuclear Arms Race"

No peace movement ever hit the United States with the strength and suddenness of the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign.

The idea of a bilateral freeze on nuclear weapons, developed in 1980 by Randall Forsberg, was consciously simple, leaving the harder questions of reversing the arms race and defusing international rivalries for later negotiations.

Forsberg's idea of an immediate freeze was simple, but not simplistic. Forsberg, who was born in Alabama, earned a doctorate in military policy and arms control from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She says, "I've made it my business to know more about worldwide armaments and use of military power than most people outside of established military circles."

Events since 1980 indicate she also knows something about what starts a movement. The freeze struck a chord with the American public, leading to the largest demonstration on any issue in the history of the United States: up to a million people marched in New York City on June 12, 1982. By September, 1982, 276 city councils, 446 town meetings, 56 county councils and 17 state legislatures had endorsed some form of the freeze resolution, and it was only narrowly defeated in Congress in 1982 after heavy lobbying from Ronald Reagan.

The freeze campaign's greatest strength is that it is a political movement spawned primarily at the grassroots level. It seems that where human survival is the issue, people find themselves coming down on the same side. To ask the question, "What is the freeze campaign doing?" is not to ask how far along it is on some national strategy, but rather to ask how each community responds to the call to halt the nuclear arms race.

In Tennessee, the various freeze groups have largely been outgrowths of already established peace efforts such as Clergy and Laity Concerned (CALC) in Nashville, a Bread for the World chapter in Maryville, the Cumberland Countians for Peace and the Chattanooga Center for Peace. Each community designs its own campaign, reflecting the diversity that is the strength of the freeze movement's decentralized organizing. When people face a task from the perspective of their own communities, they can create unique connections and coalitions. For instance, freeze proponents have received a welcome boost from some backup vocalists in the Nashville recording industry who taped several 30-second radio ads for the cause.

With the phenomenal growth of the freeze comes the need to translate numbers into results. For people in Tennessee, the question becomes, "How can we make disarmament a viable political issue in the traditionally conservative and militaristic South?"

Looking merely at the origins of the movement in Tennessee, it would seem to be a traditional, white, middle-class effort at peace. But though the freeze can be traced to these origins, there are reasons to believe that this needn't be so. As one petitioner pointed out recently at a music festival in Memphis, "I can't judge just on appearance whether or not any particular person will sign, and if you can just get them to read it, they'll almost always sign."

In Memphis, a central dimension of the arms race has made the freeze inclusive of many different people: it is increasingly obvious that the cost of the proposed increases in the military budget is being shoved onto the backs of the poor.

The freeze campaign in Memphis originally sprouted from concerns among students and faculty at Southwestern College that the consciousness of the local community be raised on disarmament issues. It quickly found support from, and moved out to include, other groups, such as Pax Christi and the Mid-South Peace and Justice Center. The result of that reaching out is Memphis's contribution to the development of the freeze movement.

In Memphis, as in other major cities, the link between military over-expenditures and steady economic decline cannot be ignored. In fact, the desire for nonviolent alternatives to international conflict is perhaps strongest among the black people who make up roughly 40 percent of the Memphis population. Seventy percent of the black people in Memphis live below the poverty level. As Catherine Howell of the Concerned Tenants of Public Housing said, "We have children and loved ones who have been to war before and it scares them. Everyone in public housing is aware of the problems of nuclear war. No one can run away from it — it threatens everyone where they live." This awareness and the encouragement of Pat Bryant, an organizer with the Southeast Project on Human Needs and Peace (see page 28), opened the door to the beginnings of a unique coalition between the Memphis freeze group and the tenants organization, a group committed to saving public housing from further cutbacks and sale to private developers. At the Waging Peace Conference held in April, 1982, during Ground Zero Week at Southwestern College, the members of the two groups began working together.

After a Saturday morning assembly, strategic and constituency workshops were held. The labor, black and education constituency groups joined forces, and out of that combined workshop (which in addition to the tenants group included representatives from legal services, the Medical Workers' Union and Southern Prison Ministries, among others) a local variant on the national freeze petition emerged. The Memphis petition not only called for a halt to the production of new nuclear weapons and delivery systems, but also stated that the money which would have paid for those systems should be transferred back to the support of human-needs programs.

As a result, both the freeze and public housing groups included this call for transfers in their petitions. Many members of the Memphis freeze campaign now see the link between the arms race and the present economic and social predicament — and the resultant process of sharing between groups working for peace and those striving for economic justice — as the fundamental issue.

There is still much work to be done by both groups to make this coalition a viable force beyond these initial efforts. But the impetus is there. According to David Stebbins of the Southern Prison Ministries, "These two groups complement each other. At the Waging Peace conference they realized that their efforts could mutually benefit each other, even though their focuses seemed on the surface to be different. When both groups work in unison, then such a coalition would be hard to ignore."

The freeze movement is at a crossroads, facing many questions — and controversies. For example, people of both Nashville CALC and the Peace and Justice Center in Memphis express concern that the popularity of the freeze might draw attention away from more established programs and hinder the establishment of other projects such as research on U.S. intervention in Central America or the Peace and Justice Center's "Enemies" project, an examination of our whole concept of "enemy."

So far, this problem hasn't proved great. Memphis Pax Christi decided that, with the establishment of the now-independent freeze group, and having focused its own efforts last year on disarmament, it can turn this year toward educating the community about alternatives to militarism and violent conflict on a local and personal, as well as national, level. William Mooney, president of Bread for the World in Maryville, pointed out that his group gives equal time to its two major concerns. "One month's meeting will be on hunger, 'the next month's on peace."

It speaks well for the freeze campaign as a grassroots movement that established peace groups are less concerned with taking advantage of the popularity of the freeze, and are more concerned that the freeze campaign be self-sustaining in each community, and welcome that development. In the words of Louise Gorenflo of Cumberland, "It has to be a grassroots movement. More energy has to be poured into those people around you to awaken them to the fact that peace is not a dirty word." In fact, the campaign for disarmament is so much a people's movement that its momentum was little affected by the narrow defeat of the freeze resolution in Congress in August.

Despite the work in Memphis to create a broader and hence stronger coalition, many people still feel that the immediacy of the nuclear threat requires us to focus exclusively on the military side of the issue, that the inclusion of the socio-economic dimension will dilute that effort.

The fear is that the freeze might close itself off from those who do support disarmament, but who may be in favor of social program cuts, or are undecided either way. These reservations seem to be based on the belief that social needs issues have been predominantly a concern of the poor, whereas military and foreign policy concerns have been largely an interest of the white middle- and upper-class; thus, the thinking goes, the freeze would do itself a disservice to alienate a powerful group, jeopardizing funding resources and stronger political effectiveness. Again, the case of Memphis suggests that this reservation might not be justified. Although a couple of individuals within the Memphis freeze group question the political prudence of making the economic connection, so far petitioning experience has not supported this view: no one has yet challenged the fact that the increase in the military budget is being funded directly by cuts in social programs.

Could this myopia have been a stumbling block to the peace movement in the past? Does it not reflect a division of perception as to who is valuable to a movement? If the freeze movement fails to include in its goals the needs of the present domestic victims of militarism, how could it expect to be anything other than peaceniks frantically moving to secure their own future existence?

One recent development of the national freeze movement which has disturbed organizers of the freeze in Memphis is the birth of a freeze Political Action Committee (PAC) to funnel money to candidates for public office. George Lord, a sociology professor at Memphis State University and a freeze activist, feels that "this spells the end of the freeze as a grassroots effort," as candidates support the freeze to receive contributions rather than as a response to public concern or their own consciences. While no freeze PAC funds have yet been spent in Tennessee, some local organizers feel that any available money could be better used on direct education of the public. Sharon Welch, who was a leader of the freeze in Memphis and who taught courses in the arms race at Southwestern, believes that if funds are to be pumped in, they should be applied at the grassroots. "By building up the movement at its base, the freeze can be popular enough that candidates wouldn't hesitate to go public with it. The numbers are out there, it's a matter of making that public vocal. It's not necessary to buy off candidates when public outcry itself is converting hawks as well." She and others feel that PACs do not promote representative democracy.

The freeze campaigns have also been noticeably weak on economics. If the freeze were implemented in 1983, more than 300,000 jobs might be jeopardized, according to Ed Glennon, editor of SANE's Conversion Planner. Glennon points out that the long-term economic effect of the freeze would be beneficial, but that "economic dislocation and personal suffering can be avoided . . . only if preparations for job and income protection are begun well in advance." Very few freeze groups include such planning on their agendas. In Oak Ridge, a group working for conversion of the Y-12 nuclear weapons facility has yet to prove to workers or the community that the disarmament movement has alternative jobs for them.

Lastly, as freeze proponents and critics alike continually reiterate, even if the freeze campaign is successful in halting the production of additional nuclear weapons, the world is not necessarily saved. Mary Ruth Robinson of the Southern Organizing Committee for Economic and Social Justice reminded Memphians, "The freeze itself only buys us time." We would still have all the warheads built thus far, ready and waiting to be unleashed. We would still not have removed the causes of war. We would not have reversed the arms race, either for nuclear or conventional weapons. We would not have significantly altered U.S. foreign policy.

Still, first steps must be made somewhere, and the popularity of the freeze proves Americans are ready for that first step. We must admit the possibility that this peace effort will not by itself be successful, and that puts pressure on us all to build the process of making peace.

Tags

Pack Matthews

David Stebbins, who did much of the research for this article, and Pack Matthews both work at the Mid-South Peace and Justice Center. (1982)

David Stebbins

David Stebbins, who did much of the research for this article, and Pack Matthews both work at the Mid-South Peace and Justice Center. (1982)