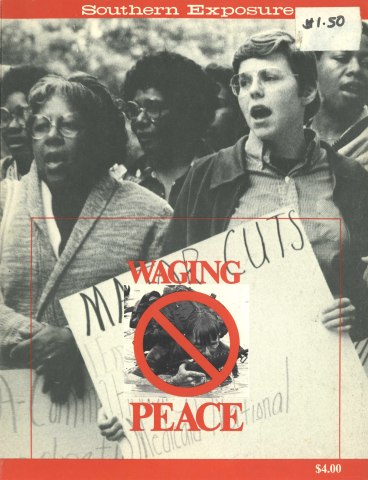

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

"If the military's racism has changed at all, it's just gotten more sly" — From Turning the Regs Around, 1974

Racism and racist violence are vital weapons of and for the making of war. Within the military's strict command system, the denial of basic rights and the highly discretionary use of discipline increase the opportunity for racially motivated mistreatment on individual as well as institutional levels and also protect prejudicial treatment from being challenged and corrected.

In a 1974 landmark decision involving a service member's court-martial conviction, the Supreme Court stated:

While the members of the military are not excluded from the protection granted by the First Amendment, the different character of the military community and of the military mission requires a different application of those protections. The fundamental necessity for obedience, and the consequent necessity for imposition of discipline, may render permissible within the military that which would be constitutionally impermissible outside it.

In other words, under the strict command-and-obey system, military personnel lose the basic constitutional protections granted them as civilians. Charlie, a black veteran who spent five-and-a-half years in the air force, including a tour of Vietnam, explains: "Racism is worse on the inside than the outside. The reason for this is because it's like being in captivity. When you're in captivity you are restricted and controlled and can't do what you want to do. . . . Your command knows they've got you."

Military regulations against mistreatment, including race baiting and discrimination, are on the books. They provide members of the military the right to file grievances against their officers for any documented wrongdoing, including cruelty, oppression and maltreatment. In spite of such regulations, the basic right to question or organize against mistreatment of any kind is severely limited.

Any complaint or challenge to authority from the troops is regarded as a threat to the power and control of the officers in command. The first signs of a critical attitude or discontentment on the part of an individual or group of service members usually lead to harassment and intimidation from the command, including the threat of reprimand, lost rank and pay, and a bad discharge. The right to fair treatment and to speak out against wrongdoing quietly lose out to the command's top priority — the control and discipline of the troops. A Department of Defense directive speaks to this partial right to expression and the highly discretionary power of the command:

The service member's right of expression should be preserved to the maximum extent possible, consistent with good order and discipline and the national security. On the other hand, no Commander should be indifferent to conduct which, if allowed to proceed unchecked, would destroy the effectiveness of his unit. The proper balancing of these interests will depend largely upon the calm and prudent judgment of the responsible Commander.

The major way that people of color in the military have effectively challenged racist treatment is through strong organization and solidarity. Without unity and numbers, efforts to address discriminatory practices have little or no impact on the military system.

In November, 1972, a navy captain on board the U.S.S. Constellation began general discharge procedures against six black sailors for having low scores on a vocabulary test. The same captain had assigned black service members to menial work on the ship. About 150 sailors, the majority of whom were black, demanded a meeting with the captain to discuss their grievances. When the captain refused to meet, the sailors staged a sitdown strike in the mess deck and refused to work. The ship returned to port. After staging a second mass refusal to follow orders while in port, the protesting sailors' list of demands were met, including an independent investigation into the actions of the captain.

In November, 1981, a black marine died at Camp LeJeune, North Carolina, as the result of untreated hepatitis and spinal meningitis. His family requested a military investigation into his death, on grounds of racial harassment and the denial of medical treatment. When interviewed about events leading up to his death, fellow black marines would not speak out about the white noncommissioned officers' persistent refusals to allow him to receive medical treatment for obvious symptoms of illness; the fear of reprisal and harassment was too great. The military investigation cleared the command of any wrongdoing.

Commanding officers can easily express racist attitudes through legitimate, routine actions. Under Article 15 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, all commanding officers can punish service members under them without trials, judges or juries, using "non-judicial" punishment, and can impose penalties including extra duty, restriction, loss or detention of pay, reduction of rank, and even correctional custody up to 30 days. In a study on racism in the military, the Congressional Black Caucus found: "No military procedure has brought forth a greater number of complaints and evidences of racial discrimination than . . . non-judicial punishment. Article 15 . . . has without doubt resulted in irreparable damage to the service careers of Blacks."

"Racism in the military is so deep . . . that we can't possibly cope with it." —Parren Mitchell

The unconditional freedom of officers to use non-judicial punishments against their troops is a powerful weapon of control. Though service members have certain rights under the system of non-judicial punishments, including the right to appeal, knowledge and use of these rights is not widespread. Non-judicial punishment is perhaps the most controversial regulation in the entire military service — in civilian terms, this procedure would mean combining the roles of the district attorney and the judge.

The fact that the officer corps does not reflect the racial diversity of the military is partially attributed to the extensive use of both non-judicial punishments and court martials in keeping people of color in the lower ranks. In 1981, 31 percent of enlisted personnel in all branches of the military were people of color, compared to only 10 percent of all officers. In Fiscal Year 1979, the most recent year for which statistics are available, black soldiers represented only 32 percent of the total army population but represented 51 percent of the prisoners in army corrections facilities. A report published by the NAACP states:

A disproportionately large number of black prisoners is serving sentences in military stockades. . . . It is of special significance that blacks were more likely than whites to be confined for offenses that involved a challenge to authority, usually a white superior officer.

The major reason that most people of color remain in the lower ranks is the job assignment and advancement procedures of the military. Persuaded to join by promises of educational and occupational opportunities, people of color enter the military and find a host of tests and rigorous training courses that must be passed before any enlistment commitments can be ensured. Recruiters never mention the serious impact of these test scores and the percentages of failure. In a Department of Defense report, the result of this procedure is recognized:

Hampered by a poor socioeconomic environment . . . the minority serviceman comes into the service where he is immediately evaluated and classified by tests he is ill equipped to master, and therefore his duties and career progression are to a large extent forecast, forestalled and foredoomed.

Charlie's experience in the air force supports the DOD's conclusions:

I was in a training program that should have taken two years but was compressed into only 16 weeks of study. Without the background and training to make it through such a highly technical training course, a person didn't stand a chance. And when anyone flunked out of their training program, the command could place them wherever they wanted. . . . I was in supply and out of 450 people in our dorm, 400 were minorities.

By the very nature of its own practices, the military creates a system similar to "slave labor," in which people of color are isolated from others and find themselves occupying the low-skilled, dead-end, service duties — including infantry, details (cleanup), supplies, k.p. (kitchen patrol), storage, fuel and transportation. Mark, a black marine, spent most of his four years working in the kitchen and mowing the large lawns at Camp LeJeune. When he was discharged, he looked back at the base and said, "About the only thing I've been trained to do is be a janitor."

This system of oppression and segregation also ensures that a higher percentage of people of color are currently assigned to hazardous duties and will be killed at a higher rate than white service members in accidents and in time of war. Harold, a black marine, was given a verbal promise by his recruiter that he could learn to be a heavy equipment operator in the marines. Instead, he was assigned to a predominantly black infantry company. In a sober reflection on his position and those of his fellow trainees, he recalls: "It came to me when we were jumping out of helicopters that, in a real war, a lot of us were going to get killed."

Over half the black enlisted personnel in 1979 (and only a fifth of white enlistees) came from families with an income of under $10,339. Since 1980, all the military branches have exceeded their designated recruitment quotas. Entrance test scores for admissions have now been raised and re-enlistment applications are being screened more closely. The class profile of the armed forces reveals a considerable move toward the middle class. In 1981, 90 percent of black recruits had a high school diploma, compared to 75 percent the year before. Seventy-nine percent of white recruits had a high school diploma in 1981, compared to 66 percent in 1980.

This move to tighten up on standards denies enlistment to those who might have been admitted only a few years ago and bars others from reenlisting in the military. As the open door to military service begins to close and reject more applicants, the race and class level of the applicants becomes more of a determining factor in enlistment and re-enlistment opportunities. Already receiving the highest percentage of early discharges and "firings" per population in the military, more and more people of color will receive rejection slips from the military.

The Quaker House Military Counseling Center in Fayetteville, North Carolina, has already seen the impact of these patterns. All three soldiers who have come to the center with concerns about being denied reenlistment in 1982 are black. The most serious case, now in appeal, involves a black sergeant who spent 11 years in the army before his reenlistment was refused.

Military counseling can play a double role in assisting people of color in the protection and promotion of their legal rights. On the one hand, counseling programs can assist young people in making an informed decision about military service and help service members know their rights and procedures for getting out of the military if they so choose. On the other hand, "Helping people get out does not solve the problem of the denial of rights for those who are in," states Bob Gosney, director of Quaker House. Military counseling programs bring knowledge, support and advocacy assistance to service members whose rights are being denied but who have no plans for seeking a discharge from military service. In a slumping economy, Quaker House is receiving more inquiries from people of color in the military who desire to know and protect their legal rights but who wish to remain in the military until there are more opportunities for civilian jobs.

Challenging the violations of human rights in the military, particularly those resulting from racism, requires the combined efforts of military and civilian advocates. A broad-based coalition of individuals and counseling, support, advocacy, human-rights, religious, congressional and veterans groups committed to racial justice must join together and press for change. In recent years, the civilian and military coalition that formed to address the issue of Agent Orange, the deadly defoliant widely used in Vietnam, is a clear example of the importance of public documentation and persuasion in addressing military practices and policies.

Challenging and changing the racism behind the military is a far greater task. For as long as the United States government or any other government in the world believes in the right of one race, religion, economic system or nation to dominate another, racism and militarism will go hand in hand in a march toward war. But the challenge of this task must not soften our commitment to the work. Every small effort to live and build a world free of arrogance and oppression is part of a growing spirit to bring on and welcome the day when dignity and justice stand tall.

Tags

Mac Legerton

Reverend Mac Legerton is director of the Camp LeJeune Outreach Program, a project of Quaker House Military Counseling Center. He is also a staff member of Robeson County (North Carolina) Clergy and Laity Concerned. (1982)