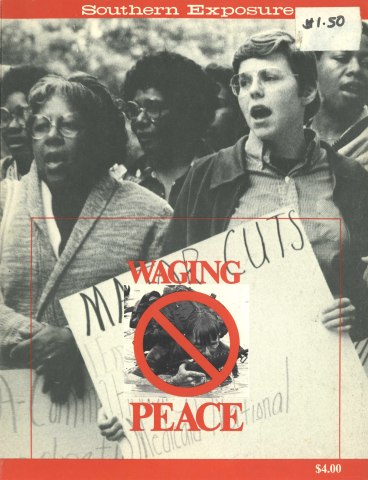

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

The Achilles heel of the organized peace movement in this country has always been its whiteness. In this multi-racial and racist society, no all-white movement can have the strength to bring about basic changes.

And basic changes are what we are talking about when we set as our goal pulling this nation back from the nuclear precipice. Thousands of people can call for a nuclear freeze within our present economic and social structures, and it is good that they are doing so. But the nuclear arms race will continue unless we organize the movement that can make a total change in the priorities of our country — turn it away from its suicidal obsession with weapons of death, and set it to using its resources for life and human development.

It is axiomatic that basic changes do not occur in any society unless the people who are the most oppressed move to make them occur. In our society, it is people of color who are the most oppressed. Indeed, our entire history teaches us that when people of color have organized and struggled — most especially, because of their particular history, black people — we have moved in a more humane direction as a society, toward a better life for all our people.

There is growing recognition of all this within white peace organizations, and there have been conscious efforts to broaden the organized peace movement to include people of color. At least some peace organizations have made efforts to deal with the internal racism that makes this a formidable task.

All this is to the good, but it is not enough. If we would meet the challenge of our times, we who are white must stop thinking in terms of bringing people of color into "our" peace movement. The crisis of humanity around the globe requires something more of the people of this country at this moment. What is required is the building of an entire new peace movement — one grounded in the grassroots of communities across our nation, and multi-racial, with a substantial part of its leadership coming from people of color. We who are white have a critical role to play in the building of such a movement, but we will not necessarily be the leaders of it; in fact, most of us will not be, and our old organizational forms must give way to new ones.

I believe that for two reasons the best possibility of beginning to build this movement is in the South: the record of the black South, and the peculiar history of the white South.

The history of our region gives the lie to a debilitating myth, prevalent in the organized white peace movement, that blacks, in general, are not interested in anti-war movements. They are so weighted-down with the job of surviving, so the popular wisdom goes, that they have no energy left to think about matters of foreign policy and world affairs.

Traditionally, in our region, anti-war movements were not separate from the Civil Rights Movement. My own memory on this dates back to the late 1940s — when I was first active in social-justice movements. The same people, black and white, who were demanding an end to the post-World-War-II terror against blacks were organizing to stop the nation's drive toward World War III. Paul Robeson was touring the South on behalf of the Progressive Party, calling for equality at home and a new world view that ruled out war. The first "freedom rides" to oppose segregation on interstate buses in the South were made up of whites and blacks — in the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the Congress of Racial Equality — who had been in jail for opposing the draft in World War II. When peace organizations met in the South, they usually found a haven in black churches. Later, Southerners who opposed the Korean War were the same people who were struggling to end segregation.

The South then was the closest thing to a police state that this country has ever known; the people who ran it, in their passion to preserve segregation, had to set up police-state mechanisms that restricted everyone. It seems only natural, in retrospect, that the same people who dared risk livelihood, life and limb to oppose the South's racial patterns also had the courage to oppose the nation's destructive foreign policy. Usually these people were black, although a significant minority of whites also took a stand.

It was the mass black movement that developed in the mid-'50s that broke the back of the South's semi-police state and opened it up to a variety of movements for social change. So in 1962, when a militant pacifist group, the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA), started organizing marches against nuclear weapons, they sent one march South. Most of the marchers were white, and they agreed at the outset that they would stay away from the Civil Rights Movement. The reasoning was that they should not "burden" that movement with "another issue."

That separation fell of its own weight the minute the marchers reached the South. The people who welcomed their controversial march were of course those who had already had the courage to stand up against the South's social patterns. Black churches opened their doors to them, and the black movement opened its heart. A year later, a second CNVA march through the South was well-integrated with the Civil Rights Movement, and some of the participants ended up in jail in Georgia.

Then, as the Vietnam War escalated in the mid-'60s, the first Southern organization to oppose it was the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) — that organization led by young blacks that provided the shock troops of the civil-rights movement. Again in retrospect, it seems natural that these young blacks who faced death on the dirt roads of Mississippi marched to the army induction center in Atlanta to say no to the draft — the first demonstration at an induction center in the country. Some of those demonstrators later went to prison for years. The next Southern organization to speak against the war was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (who had individually taken a stand even earlier), and then the Southern Conference Educational Fund, an interracial group.

The whole nature of the national anti-draft movement changed when SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael began touring Southern campuses, saying "Hell no, we won't go." Black youth, and many whites, were electrified when Muhammad Ali issued his famous statement: "No Viet Cong ever called me nigger." And the entire peace movement reached a new level when Dr. King raised his eloquent voice in a call not only for an end to the war, but for new priorities for the country, putting human life first.

People responded. I remember hearing Dr. King speak in a black church in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1967. He came there to support a mass movement for open housing, but the greatest applause came when he called for an end to the war.

Later, in 1976, the War Resisters League organized the Continental Walk to remind us that our government had launched a new military buildup. The walk had several prongs, all headed toward Washington. In the North and West, the participants were almost entirely white. In the South, starting in New Orleans and moving up through the South, with the support of SCLC, the marchers were almost entirely black. It was we who are white who failed, although some of us tried, to involve white Southerners in this action.

In the late '70s, Richard Arrington, the black mayor of Birmingham elected as a result of the Civil Rights Movement, issued the nuclear freeze petition as a proclamation, long before the national mass movement around it. Just this past summer, in 1982, it was a black organization, SCLC, which organized a pilgrimage across the South, stopping to knock on doors in 64 communities, and everywhere raised the demand that the nation stop the nuclear arms race and put its resources to work for people's needs. In August, 1982, Mayor Andrew Young of Atlanta spoke at SCLC's twenty-fifth anniversary convention in Birmingham and issued a clarion call for an end to the arms race and new priorities for the country.

Perhaps the myth that blacks are not interested in these issues has been perpetuated because white people in positions of power have continually told them they should not be. Even among sophisticated white liberals, there has been a tendency to recognize, sometimes grudgingly, a legitimacy in the struggle of blacks for their right to equality — but to assume that when they exercise this right by speaking on such "larger issues" as war and foreign policy they are stepping out of "their place."

In fact, the greatest fury of the power structure is reserved for blacks who act on these issues. It was, for example, when SNCC opposed the Vietnam War that the attacks intensified which eventually destroyed it. When Julian Bond supported that anti-war position, the Georgia legislature sought to bar him from the seat he had won at the polls. When Muhammad Ali resisted the draft, he was stripped of the title he had won in the boxing ring. Jim Grant, one the Charlotte Three who were sent to prison in North Carolina on false charges, became a prime target not only because of civil-rights activity but because he counseled black youth to resist the draft. And the fury that descended on Martin Luther King when he spoke against the war is well known.

In more recent years, with the nation as a whole turning a deaf ear to the black freedom movement, the usual way of handling positions of black leaders and organizations on foreign policy is simply to ignore them. No national press reported Mayor Arrington's stand against war. SCLC's very important grass-roots organizing work on its 1982 pilgrimage received very little media attention at best. Where it was reported it was usually presented simply as a march for renewal of the Voting Rights Act, which was only one of a number of sweeping demands SCLC was making. The media apparently recognized SCLC's concern for the Voting Rights Act as legitimate, but not the fact that it was calling on the country to change its basic direction. Andy Young's speech in Birmingham was a major statement on national policy by the mayor of a major city — but the white Birmingham press printed only one paragraph on it and nothing on his attack on militarism.

We who are white and seeking to build a new peace movement in the South must not be as blind as our national policy makers. New leadership on this issue is developing within black communities, and whites must seek it out and find out how we can fit in. Blacks often form separate organizations because these seem to be the only viable forms of struggle in a racist society. But most blacks and black organizations are also open to coalition-building — if sufficient numbers of whites are willing to deal with the life-and-death questions that racism poses. So the question of whether there will be multi-racial movements is up to us.

We do, I think, have a special role to play, for it is the support in white America that keeps Congress voting, despite all our demonstrations, for astronomical military spending. Blacks and other people of color do not flock into white-dominated peace organizations (as they have not flocked into any white-dominated organizations); they have always been disproportionately represented in our armed services (in the past because of discriminatory draft practices and now because of the "economic draft"), but there is no mass belief in the arms race among them.

Among many white people there is, and that is so because the white view of the world has been distorted by racism. Large numbers of white Americans accept the arms buildup because they accept an assumption that the United States is the zenith of civilization and therefore this country should run the world. That assumption imposes blinders that make it impossible for them to understand what is happening in the Third World. Thus, they can reduce all dangers in this revolutionary world to a concept of a "Soviet threat" and can easily accept the false notion that we can buy some kind of security for ourselves if we just build more and better weapons than the Russians.

We who are white and Southern — and who have been through the painful process of examining our own society and finding it wanting — are, I think, peculiarly equipped to deal with this situation. For us, these issues of domestic and foreign policy have always been very obviously intertwined.

For those of my generation, coming to maturity 35 years ago, it was all crystal clear. I recall my own experience — growing up in a society that was both rigidly segregated and profoundly militaristic. There was a military academy in almost every community of any size. I grew up in an army town in Alabama. Each summer, ROTC students from colleges across the South came for training; we young women always wanted to go to their dances and have summer romances with them, because their uniforms represented the essence of glamor. Congressmen from the South in those days got elected according to how loud they yelled against blacks — and how many military bases and contracts they could bring into their districts. And I, like so many whites of my generation, learned early that God had decreed the separation of the races, and at the same time had blessed our Southland with being the last best bastion of patriotism and pure Anglo-Saxon culture in our nation. It was a real fascist ideology, and it was bred into our bones.

One does not get rid of that kind of mindset without turning oneself inside out — and that's what many of us were able to do in that period. Once one could take the first step, the rest of the false structure crumbled like a house of cards. For me, as for many others, the first step was recognizing that our own society was totally wrong on race — and that we could not live in a society that created privileges for a few by the oppression of one whole group of people. Once we came to terms with that truth, it was a relatively easy process to recognize and accept the fact that our entire nation was wrong in the way it treated the rest of the world, most especially the six-sevenths of it that is non-white. I joined the peace movement at about the same time I joined the Civil Rights Movement, and I never thought of them as separate.

The Civil Rights Movement of the'50s and '60s challenged not only the South but this entire nation in ways it had never been challenged before. Just as many of us had had to search our own individual souls long before, white America as a whole had to begin to search its soul on the issue of race. That process released tremendous creative energies and set our nation momentarily on the path to more humane national policies. I think it is also what made it possible for the nation to begin to search its soul on its role in Vietnam.

Then something happened. The process of transformation was cut short. We had torn down the walls of Jim Crow in the South, and blacks had begun to win political rights. But as the momentum eased (for many reasons), we found to our dismay that the South was just becoming more and more like the rest of the country, and that was not necessarily good. We learned to practice more subtle forms of racism and went back to our old ways of assuming that power and privilege should reside in the hands of whites, both here and around the world.

As we were becoming more like the rest of the country — as the black movement and its allies broke our home-grown police state and made organization possible — a phenomenon appeared that we had never really had in the South before: all-white peace organizations. New generations of young whites — dedicated, but with little understanding of how the black movement had by its blood and tears made their work possible —began to organize First against the Vietnam War, and later against the new nuclear buildup, as if these things were separate from the issue of racism. They did good work and are doing it today, but they are weakened by their failure to realize what was so obvious in the more stark days of the South's past — that white America will not change its militaristic foreign policy until it transforms its thinking and its actions toward people of color, and that this process must begin at home.

In a sense, I think white America as a whole today stands in a position similar to that of the white South when I grew up in it - in order to save itself, it must go through that transformation process and recognize that it can and must work cooperatively with the world's people of color, instead of assuming the right to dominate. We who are white Southerners have reason to know that this transformation process may be painful, but it is not destructive; in fact, it is the road to liberation. If we can do our part in the building of a new peace movement that is based on this understanding, we can perhaps point the way for the rest of the country.

How do we begin? Large movements develop because people begin where they are, and do the long hard work of knocking on doors, mobilizing, teaching, organizing people around specific goals in which victories can be won. A number of organizations and many individuals, both black and white, are doing that in Southern communities today — and therein lies our hope.

Tags

Anne Braden

Anne Braden is a long-time activist and frequent contributor to Southern Exposure in Louisville, Kentucky. She was active in the anti-Klan movement before and after Greensboro as a member of the Southern Organizing Committee. Her 1958 book, The Wall Between — the runner-up for the National Book Award — was re-issued by the University of Tennessee Press this fall. (1999)