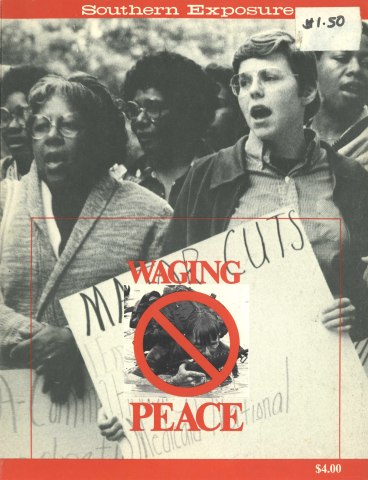

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

Religious charity and the mission of the church cannot cover up national injustice by government. Human need and social justice cannot be sacrificed at the altar of economic programs and military might.

When 63 percent of the total budget cuts are related to programs that primarily serve the poor, it is time to ask some honest and disturbing questions about this administration's priorities.

— Nathan Porter, Domestic Hunger Consultant, Southern Baptist Convention Home Mission Board

For as long as organized religion has existed on this earth, religious leaders and major denominations have issued proclamations or asked "honest and disturbing questions" about peace and about social and economic justice issues. But a carefully worded public proclamation is too often an entirely different thing from collective action by followers of the faith to implement the inspirational words.

In the South, religious groups have typified throughout our tumultuous history both the best and the worst responses to human need and suffering. Flashy mass-media manipulators like Jerry Falwell and "Reverend Ike" promise miracles to desperate listeners if they send in their dollars; all too often, the major denominations hide behind facades of pious respectability.

Nevertheless, thousands of Southerners, both black and white, have found strength through deeply held faith to act on the basic religious values of peace, justice and equality. Black churches of course figured largely in the vanguard of the Freedom Movement of the 1960s.

Today, concern about the threat of nuclear war is spreading even among the wealthy white denominations, and in some cases the connections are beginning to be made between that threat and the costs right now in human suffering caused by our exploding military budget.

What follows is a brief description of some of the actions being taken by Southern religious communities today in response to the current emphasis on military might. We realize that these listings are far from complete and urge our readers to educate us further by writing us with more news of Southern churches in action.

FROM ABOLITION OF SLAVERY TO WOMEN'S SUFFRAGE, FROM OPPOSITION TO ALL WAR TO SUPPORT FOR ALL PEOPLE'S civil and human rights, Southern Quakers have steadfastly, courageously, and often in isolation worked according to their belief that "there is that of God in everyone."

The Quaker-sponsored American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) has had a main office and several satellites in the region for more than a quarter of a century. Best known for its peace education and school desegregation efforts in the South, AFSC also sends food, clothing, medical supplies and personnel to war-torn areas of Southeast Asia, Central America, the Middle East and Africa. Regional education projects have focused on bringing balanced, peace-oriented information to community groups and the news media on the Middle East and Southern Africa. Today, in addition to working on the nuclear freeze and jobs-with-peace campaigns, AFSC conducts projects for working women in several states and helped organize the Greensboro, North Carolina, coalition which pushed the U.S. Justice Department to conduct grand jury hearings into the November 3, 1979, slayings of five anti-Klan demonstrators.

Like AFSC, the inter-denominational Clergy and Laity Concerned (CALC) stands out because of its high level of demonstrated religious commitment. CALC was organized by Martin Luther King, Jr., shortly before his death and has worked closely with AFSC through the years. Both groups are very active in teaching organizational skills and building regional and statewide coalitions on a variety of social issues, including peace.

Vigils, standing silently in protest, are a traditional nonviolent way of "speaking truth to power," as the Quakers say. Northwest Texas CALC holds monthly prayer vigils at the gate of the Pantex nuclear weapons plant in Amarillo. With the Catholic Diocese of Amarillo, CALC helps to support the Solidarity Peace Fund, established by the diocese in February, 1982, to provide counseling, social services and training for people who consider leaving their jobs at Pantex. This fund offers practical support for the August, 1981, statement of Amarillo Bishop Leroy T. Matthiesen asking workers to question the morality of the work they do and "seek employment in peaceful pursuits."

The Nashville, Tennessee, CALC chapter sends speakers to Sunday schools and churches, teaches courses on peacemaking and conducts parenting seminars to teach peace within the family. The chapter sponsored a Children's Day for Peace in observance of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Day and topped off an Income Tax Day demonstration on April 15 with a candlelight vigil which focused on military spending.

Vigils and other acts of quiet nonviolence as forms of protest might make more militant peace groups impatient, but the fact is that AFSC and CALC provide the lion's share — or should it be the lamb's share — of training, resources and personnel for peace work in religious communities throughout the South.

AFSC and CALC are by no means alone in the Southern religious-based peace movement. The North Carolina Council of Churches formed a Peace and Security Committee, made up of leaders from member denominations. In addition to conducting its own organizing and educational efforts, the committee has established a computerized resource center to help other peacemaking groups organize statewide.

Individual denominations are also beginning to move in some Southern communities and states. The Presbyterian churches in Atlanta recently hired a full-time peace education coordinator. The United Methodist Conference in South Texas held two peace conferences in San Antonio. The governing convention of the Episcopal Church, the Episcopal Bishops Council and the Episcopal Diocese of Atlanta have adopted nuclear freeze resolutions. And Pax Christi, a Catholic peacemaking group, stirred enough interest outside the Catholic community in Memphis that a new CALC chapter was formed to broaden the scope of religious peace work there.

The Southern Baptists' commitment as an institution to peace and justice issues has rarely been outstanding; yet they too are beginning to act. The Southern Baptist Convention recently adopted a nuclear freeze resolution. Even more encouraging is the appearance of The Baptist Peacemaker, published from the Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky. The Peacemaker began two years ago as a grassroots effort to encourage Baptist involvement in peace work. Volunteers work with local churches to organize Peacemaker groups throughout the South, and the seminary is writing a training guide to assist in this work. The Baptist Peacemaker does not confine its effort to its own denomination; its mailing list of 31,000 includes many non-Baptists, and in Louisville its staff works with the Council on Peacemaking and Religion, a coalition of Christian, Jewish and Islamic groups.

ORGANIZING FOR SOCIAL CHANGE ISSUES HAS ALWAYS BEEN A CHALLENGE IN RURAL AREAS, BUT DURING THE PAST few years several new groups have formed to address peace and social justice issues from a rural perspective. The Appalachian Peace Fellowship draws members from churches in nine eastern Kentucky counties; they show films and hold skills workshops to reach out to community people. Cumberland Countians for Peace, based in Crossville, Tennessee, meets monthly to organize local peace education programs. In Burnsville, North Carolina, a group of activists — many of whom are associated with Warren Wilson College — publishes a newsletter, Rural Southern Voices for Peace, which keeps folks posted on activities, organizations and issues throughout the rural South.

The United Church of Christ's Commission for Racial Justice has worked in predominantly black, rural communities of Virginia and North Carolina since the mid-'60s. Their educational and organizing efforts have consistently emphasized the links between domestic racial injustice and national policies of aggression and exploitation of Third World countries.

A February, 1982, commission-led march from Goldsboro, North Carolina, to the state capital of Raleigh tied together such seemingly diverse issues as tax-exempt status for racist Christian schools, the attempted weakening of the Voting Rights Act, Jesse Helms's anti-busing amendment, and the expansion of the military budget at the expense of the needy.

We believe that the primary responsibility of government is to ensure that the basic human needs of its people are met. Religious bodies of this community cannot fill the gap created by recent and expected budget cuts. Charity is no substitute for justice. — Louisville Council on Peacemaking and Religion

While individual denominations sponsor and support a wide variety of peace and justice programs, ecumenical peacemaking groups are growing throughout the South. Atlanta has its Interreligious Peace Coalition; 34 churches in Dallas participated in a Peace Sabbath on the last Sunday in May; and North Carolina's Raleigh Peace Initiative spearheaded a successful drive for passage of the nuclear freeze resolution by the city council. In Auburn, Alabama, the Conscientious Alliance for Peace sponsored a week of peace activity with the endorsement of groups ranging from Church Women United to the Auburn ACLU.

Many traditional peacemaking groups have been strongly criticized for concentrating leadership — and too often membership and outreach — among white, middle-class males. The barriers to black and female participation are slowly beginning to crumble as it becomes increasingly apparent that the mushrooming military budget is being drawn from the pockets of the poor, who are predominantly women, disproportionately people of color.

Alabama has seen a flurry of peace-related activity led by women and blacks. The Tuskegee chapter of Church Women United organized community-wide observances of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Day in which the current nuclear weapons buildup was tied to local unemployment and hunger. And during the World Peace March, the Tuskegee Ministerial Association enlisted black involvement in worship and in sharing experiences with the Buddhist marchers.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference-sponsored march in support of the Voting Rights Act which trekked from Carrollton, Alabama, to Washington, DC, emphasized the necessity of putting human needs before military spending. And Tuskegee peace organizer Judy Cumbee addressed SCLC's Twenty-fifth Annual Conference in Birmingham this year on the effects of military spending on social programs.

In Atlanta, the Martin Luther King Center for Nonviolent Social Change is making the issues of economic justice and peace the focus of its year-long round of activities leading to the Twentieth Anniversary of the March on Washington in August, 1983. Throughout the year, organizers will work with black churches, hold conferences and seminars, and sponsor a leadership meeting with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to build coalitions on peace and justice issues.

This boom in Southern peacemaking activity over the past couple of years signals a growing awareness of the ways in which militarism affects society. By encouraging local involvement in peacemaking and economic justice, the religious community contributes to "legitimizing" these issues for many Southerners. In demonstrating that people of faith are committed to acting upon their leaders' pronouncements for peace and world-wide economic and social justice, Southern churches can help to forge an alliance of men and women of all colors and backgrounds, whose efforts may contribute towards bringing the twentieth century to a close, not with a bang, but with this prayer fulfilled:

We seek a world free of war and the threat of war.

We seek a society with equity and justice for all.

We seek a community where every person's potential may be fulfilled.

We seek an earth restored. . . .

— Statement of the Friends Committee on National Legislation