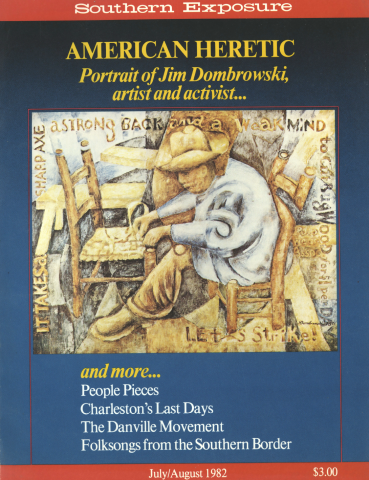

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 4, "American Heretic: Portrait of Jim Dombrowski, artist and activist." Find more from that issue here.

They wandered the Irish countryside for centuries, at first on foot, then with carts, later in caravans of brightly painted horse-drawn wagons. The Irish call them tinkers. They call themselves Travelers, and they still work with, and trade, metals.

The Travelers at Murphy Village, South Carolina, identify themselves as descendants of the Irish Travelers. One of the most common surnames — Sherlock — is the name of a large Traveler clan from the area around Killorgin County, Kerry. And they use a secret language called Shelta, composed of Gaelic, English and artificial words, that was used in Ireland to prevent outsiders from following their exchanges, particularly during a trade.

The Irish Travelers went from house to house, offering to make or repair household items such as frying pans or tea kettles. They worked in copper and cast iron, but tin was the metal of choice, being the easiest to work and requiring few tools — hence the nickname, Tinkers. Several families, usually related by marriage, traveled together in a territory or "cut" of about two counties.

The Travelers Ireland

No one knows their origin, when or why they took to the road, and Travelers themselves have no strong tradition about when they started wandering. Some scholars suggest they are descendants of a specialized caste of itinerant metal workers who served the Irish clan chiefs in feudal times.

Whatever their origin, until recently the Travelers were an integral part of the Irish economy. Stores and manufactured goods were rare in rural Ireland. Shopping required a major expedition, sometimes of 40 to 50 miles, to a market town. Livestock dealing was conducted seasonally, primarily at horse and cattle fairs. There was a ready-made economic niche for the Travelers' three skills: tinsmithing, horse dealing and chimney cleaning.

Of these trades, Travelers are most known for tinsmithing. They made mugs, gallon cans, milking vessels, buckets, stewpots, funnels and even fiddles from tin. Horse dealing was as important as tinsmithing. Travelers were expert judges of horse flesh and accomplished horse doctors.

Chimney cleaning was used as a supplemental source of cash, as was the making of small items like brooms, wooden clothes pegs and artificial flowers. The women peddled these items door to door, along with a selection of notions purchased wholesale in larger towns. According to the settled people, peddling was only an excuse for the women to get inside a home so they could pursue two other staples of Traveler life: begging and fortune telling.

Around 1950, the traditional life of the Travelers started to change. In a process still not complete, cars, trucks and tractors have replaced horses. The influx of motor vehicles also brought an increased flow of material goods. With the introduction of plastic, country people started to discard things they had previously saved for the Travelers to mend.

As Travelers sought an economic niche in the new order, the focus of their lives shifted toward the collection of metallic waste which could be converted into cash. Travelers gravitated to areas where the most scrap could be found. A new pattern of life emerged. From camps on the outskirts of cities, Travelers now range over the surrounding area in trucks collecting scrap. They also deal in used cars and auto parts, doctoring old wrecks the way they used to revive sick horses. Their businesses allow Travelers to stay in one place longer, and their camps have become semi-fixed bases.

Near the village of Swords, some five miles from Dublin's center, is a waste area the Travelers have made their own. One can wander down a long, winding lane, through a chaotic arrangement of house trailers, tents and horse-drawn caravans. Heaps of scrap and derelict cars flank the caravans. Here and there a small hut has been thrown together out of scavenged boards. Barking dogs are tied behind piles of old metal, and goats and horses graze on patches of grass between scrap heaps. Huge pots of food simmer over open fires. A car pokes slowly down the lane, stopping occasionally as the driver inquires if anyone has a transmission for a 1963 Austin for sale. Spanking new vans are parked beside house trailers sporting lace curtains. Children play in small groups beside the cooking fires. Despite the new cars and scrap heaps, the encampment exudes a medieval quality, compounded of woodsmoke, chaos and the huge overshadowing sky.

There is another kind of camp near Dublin where Travelers live in small houses with running water and flush toilets. These camps are part of the government-sponsored effort to house the Travelers — a first step toward "integrating" them into settled society. Some camps have schools for Traveler children, and social workers are assigned to help the "itinerants" adjust to settled life.

It's hard to tell what effect regular schooling and the electronic media will have on the youngest generation, but the Travelers who have chosen to be housed in the government settlement still maintain their cultural identity and socialize with Travelers on the road.

The Travelers South Carolina

For as long as anyone can remember, a group of Travelers has gathered in an area near North Augusta, South Carolina, to spend winters in a large tent settlement. When warmer weather came they would pack up and return to the road. While their history in South Carolina remains obscure, it seems certain that their ancestors came over from Ireland some time before the Civil War.

About 25 years ago, the Travelers purchased a tract of land on which 300 families now five in a cluster of trailers known as Murphy Village. Although the Travelers attend church with the "country people," the Murphy Village community is fairly self-sufficient and remains a separate world, with its own concerns and values.

The whole community gathers for the purpose of matchmaking, arranged by the children's parents, at the time of the World Series baseball games. Generations of in-group marriages have narrowed the number of surnames to just seven. Thus, nicknames have become standard: if a man is known as Red Jim, his wife will be Mrs. Red Jim, their children Mary Red Jim and Pat Red Jim.

Even with the establishment of a permanent settlement, the Murphy Villagers still follow a lifestyle much like that of the Travelers of Ireland. The village serves as home base for small working groups who range over most of the country in their pickup trucks and vans. Each group has a long-standing route to follow and generally an established clientele. Major sources of income now come from house and barn painting and linoleum sales. These low-paying enterprises, coupled with the high cost of travel, mean that the Travelers have to struggle to make ends meet.

Now that entire families no longer take to the road together, the Traveler children have begun to attend school regularly. Their parish priest hopes that education will open other possibilities for the younger generation. As in Ireland, schooling and TV are likely to have a great impact on the future of the Travelers. But their flexibility, their enduring identification with the Irish Travelers and their close-knit extended family, sometimes encompassing as many as five generations, are evidence of a powerful sense of group cohesiveness. Their determination and adaptability should serve them well on whatever road they travel.

For further information on the Travelers in Ireland, see Irish Tinkers by Janine Weidel (St. Martin's Press) and To Shorten the Road: Irish Traveler Folktales by George Gmelch (Humanities Press); on the Travelers in South Carolina, see "Colony of Nomadic Irish Catholics Clings to a Strange Life in the South," (New York Times, October 14, 1970).

Tags

Andrew Yale

Andrew Yale is a free-lance writer and photographer living in New York. (1982)