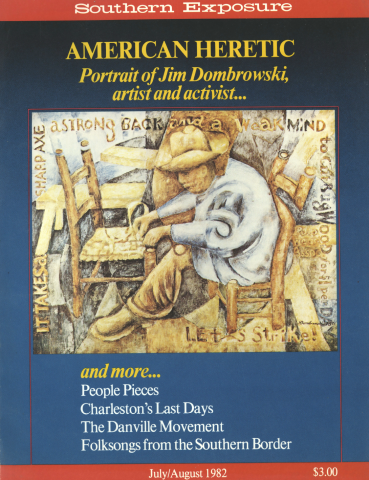

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 4, "American Heretic: Portrait of Jim Dombrowski, artist and activist." Find more from that issue here.

This article is excerpted, with the author's permission, from A Texas- Mexican Cancionero: Folksongs of the Lower Border, published by the University of Illinois Press.

English versions of the song texts are included for the benefit of those readers who may have some difficulty with the original Spanish. These are literal prose translations and not attempts at poetry. Words that are not easily translatable without a great deal of explanation have been left in Spanish and italicized.

The whole of a people's past is reflected in their songs, and the Border people of the Rio Grande are rich in both songs and history. Mid-eighteenth-century pioneers, they journeyed out into Chichimecaland, traveled north until they reached the Rio Grande, drank of its waters and traveled no more. They settled on the river banks long before there was such a thing as the United States of America, and they struck roots that would last for centuries. They clustered around the river, for its waters were life. To these people, during their first century here, the river was the navel of the world.

Once the pale-eyed strangers from the north came, the homeland was divided. The river — once a focus of life — became a barrier, a dividing line, an international boundary. Families and friends were artificially divided by it. For a long time, however, life went on very much as it had before. Officially, the people on one bank of the river were Mexicans; those on the other side were Americans, albeit an inferior, less-than-second-class type of American in the eyes of the new rulers of the land.

But the inhabitants on both river banks continued to be the same people, with the same traditions, preserved in the same legends and the same songs. Together they entered into a century-long conflict with the English-speaking occupiers of their homeland. Time has changed things, as the governments from Washington and Mexico City have made their presence felt. Even so, the bonds reaching across the river have not been broken, just stretched out a bit to meet the demands of two forms of officialdom, originally disparate but growing more like each other day by day.

I started "collecting" these songs around 1920, when I first became aware of them on the lips of guitarreros and other people of the ranchos and towns. Few of those singers are alive today. Nacho Montelongo, who taught me the first chords on the guitar, and many of his songs, still farms on the Mexican side of the river. But most of the others are gone. Some were voices stilled in their prime. I shall always remember Miguel Moran, who landed with the first assault wave on Attu in 1943, with his guitar strapped to his pack, and who came home to die, still carrying that guitar; and Matias Serrata, who landed in France in 1944, and who never came back. It is less painful to think of others who did live out their lives — Nicanor Torres, for example, who lived to be a hundred and could still sing corridos at that age. There are many others who will not sing again: Alberto Garza, in his time one of the best-known singers on the Texas side; Jesus Flores, blind singer and decimero, Ismael Chapa, itinerant merchant and singer, also blind; Jose Suarez, el Cieguito, for half a century the dean of Border guitarreros. Those and many more — young and old, relatives and friends — all part of a tradition that has not died but only changed.

My main interest has been in the meaning the songs have had for the people who have sung them. It is their cancionero.

Border singers were of many types and had many singing styles, so it is not easy to generalize about them. Women were important in the transmission of songs, though they were not supposed to sing "men's songs" such as corridos and rarely did so in public. Usually they sang at home, almost always without accompaniment, not only at their household tasks but when the family gathered in the evening, at which time all family members might sing in turn. It was rare for women to sing very loudly; in fact, all singers in these intimate family gatherings usually sang in soft or medium voices, in keeping with the tone of respeto that was expected within the family.

The extended family was important in Border social life, in the towns as well as in the rural areas. Large gatherings composed of the families of brothers, sisters and cousins were frequently held. They usually took place at the house of a parent or uncle of the nuclear families, or failing that at the home of one of the older family heads.

Women took active part in these gatherings but were less likely to sing before the whole group, more because they were occupied at other tasks than because of any taboo. Extended family gatherings always involved feeding men and taking care of children on a larger scale than usual, and there was always conversation with female relatives to occupy a woman's time.

Border society, however, was not so rigid that it did not allow exceptions. There were women who became well known as singers without losing their status as respected housewives, though they were likely to be viewed as somewhat unconventional.

Dona Petra Longoria de Flores of Brownsville was one of these exceptions. She loved to sing corridos, something few women of her generation did. But then, she always had a flair for the daring and the unusual. As a young woman in the early years of the century, she decided she was going to ride the train from Brownsville to San Antonio, and she did so all by her unescorted self. Dona Petra retained her youthful outlook until the end of her days. I have a vivid memory of her at the age of 82, bursting into her living room from the kitchen to sing us "Malhaya la cocina, " a half-plucked chicken in one hand and a fistful of feathers in the other.

What some Anglo-Americans have called a "lonesome" kind of singing was typical of casual audience situations. Such singing was always unaccompanied by instruments, with long pauses between phrases, slow tempo and free meter.

Women working in the household or men doing chores around the house often sang softly to themselves in the "lonesome" way, with no audience intended but themselves. The same type of singing was common in the fields when small groups worked together hoeing cotton or shucking corn. If women were in the work group, they might also take part in the singing, though they did not predominate as performers in this kind of situation.

Singing in the fields was never group singing, done in chorus. It was always individual singing, though there might be brief moments when two or three singers would harmonize. Not everyone in a working group performed. Each group had two or three who were recognized as the most pleasing or the most enthusiastic

singers (los mas cantadores). The others listened as they worked, pacing themselves with the music and making joking comments and criticisms about the singers.

Men working on horseback also sang in much the same style, though with some important differences, perhaps because women did not take part in their activities. Their performance was usually higher pitched and at a slightly faster tempo. It was also much louder, with a few reflective gritos here and there. While the singer in the fields sang only loud enough to be heard by his fellow workers, the man on horseback seemed to take in the whole landscape as his potential audience.

Men walking or riding along lonely roads at night — whether alone or in groups — used the markedly slow-tempo style used in the fields, but they sang the loudest of all. If there

were two or more of them, they would harmonize. Like the men working on horseback, they took everyone within the range of their voices as a likely audience. And it was quite an experience to sit outside on a still, dark night and hear their distant, lonely music.

The songs used in "lonesome" singing were chosen not for their subject matter but because they fitted the tempo of the situation. Most commonly sung were old danzas, some decima tunes, love songs and a few corridos. Romantic danzas and condones like "Triguena hermosa" were quite proper for singing among mixed groups in the fields.

Perhaps it is no longer necessary to minimize our Spanish heritage in these days of chicanismo. Too many chicanos have gone to the other extreme from their "Spanish-American" elders; they see themselves exclusively as children of Cuauhtemoc. But Spain has given us many things besides part of our ancestry. It is well to remember that, whatever the genetic makeup of the settlers who moved into the frontier provinces, what welded them together into one people were the Spanish language and the Spanish culture.

Another thing Spain gave us was her folksongs. When they came to the Rio Grande, our ancestors brought with them many songs of Spanish origin. It was the Spanish ballads with universal themes that struck deep roots among the people of Mexican culture, ballads in which people are simply people rather than historical characters identified with a specific place and time.

Our "Ciudad de Jauja" probably descends from one of the eighteenth-century romances. Words and music, however, are in the form of the Mexican corrido, and the language has also been Mexicanized. It is of Mexican good things to eat that Jauja is made. "La Ciudad de Jauja" is a comic song, but during hard times on the Border the humor has become a bit pointed. "Jauja" was widely sung during the Depression of the 1930s, for example. For many generations, Border Mexicans have gone north in search of jobs and better living conditions. In a tongue-in-cheek way, they sometimes have described their journeys as a quest for the mythical land of Jauja.

Intercultural conflict has been the most important characteristic of the Texas-Mexican Border, even before the Rio Grande became an international boundary line. In 1836, the English-speaking settlers of Texas threw off Mexican authority. Immediately they began to move in on other areas of what was then northern Mexico, their first target being the northern part of Tamaulipas — the territory between the Nueces and the Rio Grande. Manifest Destiny mounted a sustained assault on the Rio Grande communities, the armed conflict taking three forms: incursions by Anglo-American raiders and cattle thieves; large-scale raids by Plains Indians, especially the Comanches; and civil wars among the Rio Grande people, as new political influences brought by the Anglo-American invaders caused divisions among the Mexicans themselves. The result was the wrecking of the Rio Grande economy and the incorporation into Texas of the Nueces-Rio Grande area. This early period of conflict ended in 1848, with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the establishment of the Rio Grande as an international boundary.

Juan Nepomuceno Cortino belonged to one of the old landholding families on the Rio Grande. In 1846 he was among the ranchero irregulars who fought alongside Mexican troops at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. After the war he tried to live like a good American citizen, but he soon became embittered by the actions of Anglo fortune-makers in the area. One day in 1859 he rode into Brownsville and found city marshal Robert Shears pistol-whipping a vaquero who worked for Cortina's mother. Cortina intervened, shot the marshal and rode out of town, taking the vaquero with him.

He rallied a number of rancheros to his cause and outlined his grievances in a plan or manifesto. Then he attacked and occupied Brownsville in an effort to punish the men responsible for the abuses suffered by his people. In spite of what has been written about him by most Anglos — and by some chicanos as well — Cortina did not take up arms to rob the rich and give to the poor. He was no "Robin Hood." His motives were basically political; what he was trying to give all Mexicans in Texas was dignity and social justice.

Cortina's war of protest ended when he was defeated and driven out of Texas by the U.S. cavalry. He continued to operate as a guerrilla both before and after the Civil War. During the French occupation of Mexico he was a general on the republican side and took part in the battle of the Cinco de Mayo. He was also an enganchado or Union agent working against the Confederates during the American Civil War. In 1876 Cortina was arrested and confined to Mexico City for the rest of his life, on orders of Porfirio Diaz. He was allowed to make one trip to the Border in 1890 and died in 1892.

The corridos about Cortina date back to the late 1850s and the early 1860s. Apparently, several corridos about Cortina were sung, but only

fragments have survived. "El General Cortina" as it appears here is made up of three stanzas from three different corridos about Cortina.

Everyone has heard of the famous cattle drives to Kansas, the subject of many a Western. What is not so well known is that it was cattle owned by Mexicans and Texas-Mexicans (some legally obtained from them and some not) that formed the bulk of the herds driven north from the Nueces-Rio Grande area, the so-called cradle of the cattle industry in the United States. Not all cattle that went north were driven by Anglo cowboys. Many of the trail drivers were Mexicans, some taking their own herds, others working for Anglo outfits. The late 1860s and early 1870s was a period when a good many Mexicans still were duenos on the Texas side. In this respect they could meet the Anglo on something like equal terms.

But the Texas-Mexican possessed something else that gave him a certain status — the tools and the techniques of the vaquero trade, in which the Anglo was merely a beginner. The Mexican with some justice could feel superior to the Anglo when it came to handling horses and cattle, or facing occupational hazards such as flooded rivers. These attitudes are apparent in the corridos about the cattle drives to Kansas, pronounced "Kiansis" by Border rancheros. I first learned a complete version from one of my granduncles, Hilario Cisneros, born in 1867, who learned it from the vaqueros who had made the first trips on the trail to Kansas.

The period from 1900 to 1911 was a time of transition both in Mexico and in the United States. In the United States certain sections of Anglo society were becoming more and more conscious of social and political issues. "Anarchists" were still vigorously persecuted, but there was a feeling of change in the air. In Mexico things were building up toward the Revolution. Ill feeling against the United States was part of the revolutionary mood. The common person in Mexico could get worked up over rumors that North Americans had bought the cathedral in Mexico City and would turn it into a big department store. Reports about lynchings of Mexicans in Texas were the cause of anti-American riots in Mexico City and other urban centers.

On the Texas-Mexican Border, this period is marked by corridos such as "Gregorio Cortez." No other Mexican-American corrido has been more widely known. It has been reported wherever Mexicans are found in the United States, not only on the Border but on the West Coast and in the Great Lakes areas. Many other corrido heroes — such as Cortina and Rito Garcia — had preceded Gregorio Cortez, but in Cortez's life was epitomized the idea of the man who defends his rights con su pistola en la mano.

In Karnes County on June 12, 1901, Cortez shot and killed Sheriff Brack Morris, who seconds before had shot Cortez's brother. The sheriff was trying to arrest the Cortezes for a crime they had not committed. Cortez fled, knowing that the only justice available to him in Karnes County would be at the end of a rope. In his flight toward the Rio Grande, Cortez walked more than 100 miles and rode at least 400, eluding hundreds of men who were trying to capture him. On the way he killed another Texas sheriff, Robert Glover of Gonzales County; he was also accused of the death of Constable Henry Schnabel.

Exhausted, on foot and out of ammunition, Cortez was captured near Laredo. His case united Mexican-Americans in a common cause, and there were concerted efforts for his defense in the courts. The legal battle lasted three years and included reversals of a couple of speedy and unfair convictions. Finally, Cortez was acquitted of murder in the deaths of Sheriff Morris and Constable Schnabel, a significant victory in the long fight that has been waged by the Mexican-American for equal treatment in American courts. Cortez was sentenced to life imprisonment, however, for the death of Sheriff Glover. Governor O.B. Colquitt pardoned Cortez in 1913.

Gregorio Cortez and the corrido about him are a milestone in the Mexican-American's emerging group consciousness. A number of tentative organizations resulted from the court fight on his behalf. The readiness with which Mexicans in the United States came together in his defense showed that the necessary conditions existed for united effort.

The pocho appears at the time of the Revolution in Mexico, when great numbers of Mexican refugees of all social classes settled in cities like Los Angeles and San Antonio. During this period the "Mexiquitos" in the larger cities of the Southwest exhibited two contrasting states of mind. One was a truly refugee state of mind, cultivated especially by the middle-class Mexican but adopted by all older Mexicans, according to which the Mexican's life in the United States was to be insulated from Anglo influences and activities and devoted to the dream of returning to Mexico.

Another state of mind was found among the younger people in the barrios, who were being forced to adapt to the environment of Anglo cities and who found acculturation an inevitable product of their fight for survival. It was the barrios that produced the pocho, the early version of the chicano. And it was in contemptuous reference to the young Mexican-Americans of East Los Angeles, children of migrant workers and middle-class revolutionary refugees alike, that Jose Vasconcelos is said to have first used the term pocho. Whatever the degree of Americanization, the average Mexican-American of this period continued to think of himself or herself as

possessing a "pure" Mexican culture. It was always the other fellow who was an agringado, not him.

The immigrant might have exaggerated ideas about the material riches of the United States, but he did not admire its culture. He fully intended to go back home after he had got his share of the good things to be had in Gringolandia. After all, there was no place like Mexico, and within Mexico there was no place like one's own region and one's own home town.

These songs mean a great deal to me, though I am not by any means alone in treasuring them. There are others of my generation along the Rio Grande who still remember, for whom success in the contemporary marketplace has not been accompanied by a sense of shame in their old ranchero background. For them, as for me, these songs still stir echoes. But the echoes have deeper overtones, reaching beyond those fronterizos who still can contemplate or recapture what they have been. These songs should have resonance for all Mexican-Americans, for they are part of the history of all Mexicans in the United States. They record an important aspect of the Mexican-American's long struggle to preserve our identity and affirm our rights as human beings.

It has been a struggle played out in many settings — in isolated villages of New Mexico as well as in Border

"gateways" like Brownsville and Laredo, in urban centers like Los Angeles and in little towns like Crystal City. Nowhere was the conflict longer and more sustained than on the Lower Rio Grande Border. The Border was a wild and unruly place, or so they say. To put it another way, it was a focus of international conflict, based on the Borderers' resolve de no ser dejado, not to take it lying down. For thousands of young Chicanos today, so intent on maintaining their cultural identity and demanding their rights, the Border corrido hero will strike a responsive chord when risking life, liberty and material goods defendiendo su derecho.

Tags

Américo Paredes

Américo Paredes, a native of the Texas-Mexican Border country, is a professor at the Center for Intercultural Studies in Folklore and Ethnomusicology at the University of Texas. This article is excerpted, with the author's permission, from A Texas- Mexican Cancionero: Folksongs of the Lower Border, published by the University of Illinois Press. (1982)