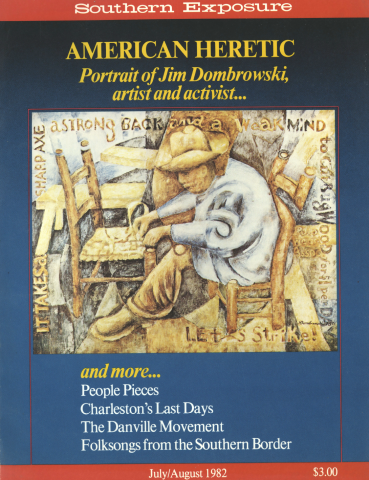

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 4, "American Heretic: Portrait of Jim Dombrowski, artist and activist." Find more from that issue here.

I went to school

and they taught me a

couple of languages

besides this one.

They even taught me

how to teach them.

But they didn’t teach me how to think

or lacking that,

a couple of lines

that might fill in

in awkward situations.

I don’t have anything to say.

These poems are really a collection of monologues and dialogues with people I have met in the Appalachian region. Some of the individual pieces are from conversations that took three minutes; others took 20 years. Some began with just a phrase heard while I was sitting at a bar somewhere or standing in line at the grocery store. A few are almost direct quotes. For some, I pulled out my notebook on the spot and asked if the person minded if I copied down his or her remark. Other notions waited months before I knew how to use them.

The collection started because I began to hear the poetry in the language of the region. As a child, I remember trying to educate my cousin who wanted to return to Indiana talking like we did in the mountains. We spent hours, days, but she still sounded more like an eight-year-old Scarlett O’Hara than anybody I knew.

The real lesson was learning to listen to words. It is difficult to admit to learning something as important as that a third or more of the way through life.

Listening has become a habit, maybe an addiction. At any rate, there are a whole lot of People Pieces, close to 200. Some are funny, some sad, some harsh. I have 60 or so that I really like and like to use. These days I read/perform these People Pieces in many different situations including schools, service clubs, citizen action groups, bars, Wednesday night dinners at the church, art festivals, you name it.

The pieces speak directly to issues because they are from real people, and they do it in a way that is not confrontational. They cross social and cultural lines of communication. Listeners find themselves understanding and learning from folks they are not even accustomed to hearing, much less paying any attention to. Those whose words I use are continually surprised, flattered, perhaps empowered, to find there is something important or beautiful or entertaining in what they say.

Sometimes I feel like I have a mission. Each time I get a phone call or someone stops me on the street (it happens regularly) and says, “You need to come by and talk with my neighbor,” or “I got a story you ought to hear,” the feeling is reinforced. These days, I have the privilege to speak for someone else. It wasn’t planned or even dreamed when I began writing the People Pieces. It has just grown up that way.

I used to work down

the dye section,

hey, hey. . .

They paid me good too.

A hundred and fifty’s a awful lot

to carry home with you

every week

thirty years ago.

But I quit,

I’d come back home from Detroit

to take that job

and I quit.

They told me I was crazy

cause I couldn’t make

that much money anywhere else

and they were right about that.

But let me tell you,

it wasn’t crazy,

it was scared.

I use to wake up

middle of the night

and whatever side I’d been sleepin’ on

I couldn’t feel it,

couldn’t move,

and I’d think it’s just me

and wait for awhile

and the feelin’d come back.

But one afternoon

down at the plant,

this boy —

he worked on line,

now I didn’t work on line —

but this boy froze up.

His arms locked up

in front of him

and it’s a week

before he got the feeling back.

And I got to thinking

maybe it just wasn’t me

feeling so funny of an evening

and I quit.

Now I’m telling you the truth,

I’m seventy-four years old

and it’s been thirty year

since I worked down there,

but you know somethin’. . .

Of them that stayed

and alot of ’em was younger than me

but of them that stayed

there ain’t one alive today

to tell about it.

Right after I left

I thought, you’re crazy, Lee,

leaving a job

pays so good.

And I went down

to Florida

bummin’ around awhile

cause I couldn’t find work.

But I’m alive, I’m alive,

and I feel awful funny sometimes

about them that ain’t.

Mountain people

can’t read,

can’t write,

don’t wear shoes,

don’t have teeth,

don’t use soap,

and don’t talk plain.

They beat their kids

beat their friends,

beat their neighbors,

and they beat their dogs.

They live on cow peas,

fat back,

and twenty acres straight up and down.

They don’t have money.

They do have

fleas,

overalls,

tobacco patches,

shacks,

shotguns,

foodstamps,

liquor stills,

and at least six junk cars

in the front yard.

Right?

Well, let me tell you:

I’m from here,

I’m not like that,

and I’m damn tired of being told I am.

Broke

is not sissy-footin’ around

sayin’ “I can’t, I’m broke”

holdin’ a twenty dollar bill

in your pocket,

or hollerin’ about bein down

to the wire

with a dollar or two in the checkin’

and a whole wad’s not been touched

in the savin’s.

That’s poor-mouthin’.

Broke

is out of all liquid assets

includin’ the ones in the pop-tops.

Broke

is cruisin’ the house

lookin’ for somethin’ to sell.

Broke is when I hock my daddy’s rifle.

You can ask me where’s the gun

and if it’s down at Bud’s

you know the times are bad.

Really broke:

Hock money’s run out

and no more credit at the bar,

I sell whatever I’m drivin’.

Broke and in trouble with the law:

I put the red truck up

and borrow money against the title.

Never got down worse than that.

One day,

I’m gonna write a letter

to those folks in Washington.

You know what I’m gonna say?

I’m gonna say

“we don’t need more roads.”

We got more roads now

than we fill up potholes on. . .

and ever’where you look,

there’s some new one goin’ in.

What I’m gonna tell those folks

up there is this:

There’s roads enough right now

that people wants to live

on big ones, can,

and people wants to live on little ones

can do that too.

More big ones is gonna get

more people too,

and we don’t need no more people.

Most of all,

we don’t need more new roads.

It’s gettin’ to where

you can’t give a person nothin’ anymore

and it’s too damn bad. . .

My neighbor could look

the devil in the eye

and say “no thanks,”

he didn’t want to go to hell

while at the same time

tryin’ to slip Jesus Christ

a couple of dollar bills

for the free gift of salvation.

He’s a hard man

and he’s about to drive me crazy.

Fifty cents he puts in my mail box,

or a dollar or somethin’

and all I did was give his wife

a couple ’a tomatoes

and a mess of old string beans.

And they ain’t rich.

Yesterday I picked a half a bushel

a little ole zucchini squash

and I carried five or six over

and put ’em on his porch

with a note that said

“These are a present.”

Present was underlined.

And today, there’s a dollar

in my mail box!

The man don’t understand

he’s doin’ me a favor

when he takes and

eats them damn zucchini

and when he pays me for ’em. . .

Lord, it’s me ends up beholdin’ to him.

I ain’t had no night

ain’t had no day,

ain’t had no two weeks, either.

Hell, I ain’t had no month

when you come to it.

The dog chocked,

the car wrecked,

the old man died,

(‘course we’d been expectin’ that)

and now,

I got a broke toe

come from where

I dropped a skillet on my foot.

Ain’t had no month to speak of,

that’s the truth.

If the next one don’t get better,

ain’t likely gonna’ be no me

to speak about it.

Amen.

Law, you know who’s living

down in Jack’s old house?

Lucy.

And Jack

and his family

moved down where

George used to live

before he moved out to the country.

Well, George broke his leg

and come back

and moved in with his cousins

right next door

to where I used to live

when you all had the house

across the street.

Ritchies live there now,

where you lived.

Well, the people who lived

on the other side —

moved in after you left, I think —

live in my old house now.

Has more yard.

Well anyway,

that house next door,

the one Lucy moved out of into Jack’s old place. . .

Well, George ain’t gettin along too good

with his cousins right now,

and he’s thinking about moving in.

Some of these pieces were developed for Chatauqua 77, a show produced by The Road Company. The time with The Road Company gave me the opportunity to develop the form. Thanks are in order. —Jo Carson

Tags

Jo Carson

Poet, playwright, and author Jo Carson is Southern Exposure’s fiction editor. (1995)