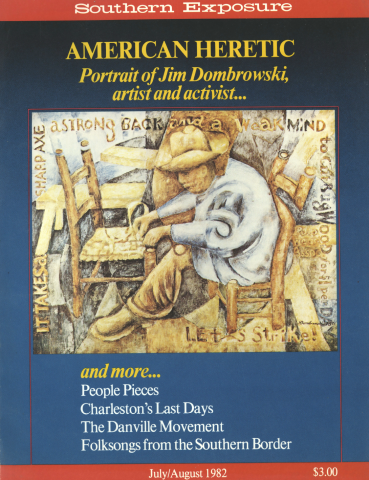

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 4, "American Heretic: Portrait of Jim Dombrowski, artist and activist." Find more from that issue here.

Not so long ago prospective voters in many Southern states had to pass a literacy test. What was so bad, one might wonder, about a simple demonstration of the ability to read and write?

The reality of the literacy test was not so simple. Of all the legal devices used to disenfranchise black people in the South, the so-called literacy test was the cleverest and most persistent. Complex in design, but simple in perversity, the literacy test came in many different forms but was uniformly malevolent in purpose. Defended as the proper screening instrument for an educated electorate, it had nothing to do with intelligent voting.

Although literacy tests were banned by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, there is abroad in the land today a feeling that blacks have had their turn; that affirmative action programs and quota systems are unfair to whites; that the federal government should dismantle its “cumbersome” regulations in the name of freedom at the local level. President Ronald Reagan has proclaimed the New Federalism of decentralization in order to “Strengthen the discretion and flexibility of state and local governments.” In so doing, he has sent an encouraging signal to those who have never accepted the national government’s role in matters of civil rights. In these circumstances, it is worth recalling just how devious local officials could be in denying black people the right to vote; how ingenious were the techniques to circumvent the Constitution, even in a time of vigorous federal enforcement; and how precarious these protections are in a climate of national indifference.

In the seven Southern states with the largest black populations, literacy tests proved to be potent “engines of discrimination.” They were developed in Mississippi (1890), South Carolina (1895), Louisiana (1898), North Carolina (1900), Alabama (1901), Virginia (1902) and Georgia (1908), as the Deep South concocted schemes for the preservation of white political power.*

Blacks had won the right to vote in 1870 through the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, but whites had regained control through economic intimidation and organized violence as federal concern for civil rights dissipated. Yet blacks, for example, made up a clear majority of the population of Mississippi in 1890 and still represented a threat to that control. To preserve an ostensible reverence for the law, it was important that the disenfranchisement of black people be legalized. For this purpose, each of the states which would enact a literacy test held a convention to revise its constitution.

The delegates to these conventions made no secret of their purpose. Said J. Z. George of Mississippi: “Our first duty is to devise such measures, consistent with the Constitution of the United States, as will enable us to maintain a home government, under the control of the white people of the state.” A decade later, an Alabama delegate was equally blunt: “It is our intention, and here is our registered vow to disenfranchise every Negro in the state and not a single white man.” And Senator Carter Glass of Virginia told his colleagues: “Discrimination! Why that is precisely what we propose.”

The convention movement and other legislation produced a myriad of disenfranchising instruments: poll taxes, property restrictions, lengthy residency specifications, white-only Democratic primaries, “good character” and voucher requirements, grandfather clauses** and “educational” qualifications in the name of literacy.

The effect of these measures was immediate and sweeping. In Louisiana, black registration fell from 130,344 in 1897 to 5,320 in 1900. (In that same period, white registration also dropped, but by much less — from 164,088 to 125,437.) By 1910, there were only 730 blacks registered statewide, and 27 of the state’s 60 parishes showed no black voters at all. In Alabama, black registration was approximately 100,000 in 1900 and 2,980 in 1903. By then it was only 3,573 in Mississippi and 2,823 in South Carolina.

For the next half-century, literacy tests had to be invoked only sporadically, for the other devices accomplished the same goal more efficiently. But with the demise of the white primary in 1944, the literacy test became the last line of legal defense for white political control. For the next 20 years, Southern governments demonstrated remarkable agility in preserving that control against increasing pressure from the federal government.

LITERACY TEST TYPE 1: READING AND WRITING

Three states (North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia) tested only the applicant’s ability to read and write. This might appear to be a straightforward examination. In practice, however, many opportunities for arbitrary action existed, for the ability had to be demonstrated “to the satisfaction of the registrar.”

In his 1940 study The Political Status of the Negro, Ralph Bunche cites the case of a black school teacher:

The registrar asked me to read a section of the Constitution, which I did, and then asked me to define terms, which I knew was not part of the North Carolina law. I said to him, “That is not part of the law, to define terms,” He said, “You must satisfy me, and don’t argue with me.”

Virginia invented one of the cleverest instruments of all: the blank form. The state code required that the applicant provide 15 pieces of information (address, occupation, length of residency, ward number) precisely “in his own handwriting, without aids, suggestions or memorandum.”

Two versions of the application form were printed, for use at the discretion of the registrar. The one usually given to whites listed the simple questions specifically. The form often presented to blacks was, except for a brief quotation of the law at the top of the page and a signature notation at the bottom, a blank sheet of ruled paper!

In the arbitrary administration of this application form, Virginia fulfilled the hope of a delegate to its 1902 convention:

I do not expect [the literacy test] to be administered with any degree of friendship by the white man to the suffrage of the black man. I expect the examination with which the black man will be confronted to be inspired with the same spirit that inspires every man in this convention.

LITERACY TEST TYPE 2: CONSTITUTIONAL INTERPRETATION

As deceptive as the reading/writing tests were, the second type of literacy test was a marvel of simplicity. Applicants had to demonstrate their understanding of the state or federal constitution by giving a “reasonable” interpretation of it to the satisfaction of the county registrar. Four states had such provisions: Mississippi, Georgia, Louisiana and Alabama.

Mississippi’s notorious Senator Theodore Bilbo gloated in 1946 over the deliberate racist design of this rule:

What keeps em from voting is Section 244 of the Constitution of 1890, that Senator George wrote. It says that a man to register must be able to read and explain the constitution when read to him. . . . And then Senator George wrote a constitution that damn few white men and no niggers at all can explain.

The local registrars had complete discretion to select the clause for interpretation and judge the acceptability of the response. The investigations of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, as well as numerous federal court cases, document the arbitrary administration of this test.

In Issaquena County, for example, whites most frequently had to explain this section: “The Senate shall consist of members chosen every four years by the qualified electors of the several districts.” Not only was it a simple statement, but any interpretation from a white person was acceptable, no matter how grossly irrelevant. One wrote only “equitable wrights,” and was passed; another wrote, “The government is for the people and by the people,” and passed.

Blacks, on the other hand, confronted complicated sections on alluvial land and equity court jurisdiction and a labyrinthine clause on taxation. In 1964, all 640 of the eligible whites in Issaquena County were registered; the voting rolls listed only five of the 1,081 adult blacks. In An American Dilemma, Gunnar Myrdal quotes a Georgia registrar, responsible for administering a similar test, who boasted: “I can keep the President of the United States from registering, if I want to. God, Himself, couldn’t understand that sentence.”

LITERACY TEST TYPE 3: CITIZENSHIP KNOWLEDGE

These same four states also used the third type of literacy test: the citizenship knowledge test. Unlike the constitutional interpretation examination, these generally had a stated passing score to enhance their “objectivity.” But the questions were often impossibly technical; coupled with the constitutional interpretation requirement, they erected an impassable barrier to blacks since, as usual, the local registrar still controlled the grading.

In Mississippi, the “citizenship test” consisted of a single item on the application form: “Write in the space below a statement setting forth your understanding of the duties and obligations of citizenship under a constitutional form of government.” Since this was linked to the equally subjective constitutional interpretation challenge, it was no wonder that as late as 1964, black registration stood at 6.7 percent for the entire state, by far the lowest in the South. Alabama demonstrated exceptional adaptability in defending its registration tests in the face of increasing federal pressure. Its 20-year game of resistance had four phases.

Phase 1. After the 1946 adoption of the so-called Boswell Amendment (requiring an explanation of the Constitution and an understanding of “the duties and obligations of good citizenship under a republican form of government”), local boards typically questioned blacks at length, while often giving perfunctory attention to whites. Birmingham blacks faced “citizenship” questions such as “How old are your wife’s father and mother?” or “Who is in charge of street improvements in Birmingham?”

Phase 2. When the U.S. Supreme Court declared the Boswell Amendment unconstitutional in 1949, the state instituted a standardized registration form. It was four pages long and remained in use from 1952 to 1964.

The questions were guileful and the format confusing. Ambiguous items asked for the applicant’s biographical data in a manner calculated to lay traps. Page after page of the constitution had to be copied literally. And the entire form had to be completed with absolute precision and no assistance from the registrar.

In testimony at the Civil Rights Commission’s 1958 Montgomery hearings, Dr. William Hunter, Dean of the Tuskegee Institute School of Education, described his experience with this process. On his first attempt, he stood in line all day. But because the board permitted only two blacks at a time in the registration room (a separate facility from the one used by whites), he couldn’t get in.

After his third day-long wait, Dr. Hunter reached the office and spent two hours filling out the form, most of the time consumed in copying a long passage from the U.S. Constitution. Then he signed the oath of allegiance, had a friend vouch for him and attached the required self-addressed envelope to his application.“I was told I would hear from the board if I passed and, of course, I didn’t hear from the board. I waited six months before I tried again. . . . I have not heard from them yet.”

Phase 3. Alabama shifted to an even more difficult form in 1964. Its civic-knowledge questions were relatively easy (the number of stars in the American flag, the name of the president, the capital of Alabama), for its caprice lay elsewhere. Applicants were required to read aloud sections of the Constitution and pronounce to the satisfaction of the registrar words like “construed,” “enumeration” and “respectively.” Furthermore, they had to write with precise spelling such words as “emolument,” “prescribed” and “tranquility.”

Phase Four. When U.S. District Court Judge Frank Johnson enjoined the use of this form in 1964, and Congress outlawed oral tests in that same year, Alabama quickly responded with the “citizenship literacy test” of 1964-65. Prospective voters had to copy a passage from the Constitution. Then they had to provide written answers to questions on such constitutional issues as habeas corpus, impeachment and ex post facto laws as an index of their “reasoning ability.” Finally, they had to demonstrate their “civic knowledge” by answering a series of difficult questions.

In 1964, there were no black voters registered in Wilcox or Lowndes County, Alabama, of 11,208 eligible, and barely 23 percent registered statewide, compared to 70.7 percent of the eligible whites.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 finally halted the use of the literacy test. The act also established a triggering formula: in states or counties where fewer than 50 percent of the voting-age residents were registered or had voted in the 1964 presidential election, and where literacy tests or similar devices were in use, discrimination was assumed. Originally, the act applied to only seven states under the triggering formula (Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana,

Mississippi, South Carolina, Virginia and Alaska), as well as parts of four others (40 counties in North Carolina, four in Arizona, one each in Hawaii and Idaho). Extensions of the act in 1970 and 1975 broadened coverage to include parts of 12 other states. Although the key provisions of the act are due to expire in August, 1982, unless extended yet again, Congress in 1975 made the ban on literacy tests nationwide and permanent.

The literacy test has been put to rest. But the nails in its coffin are not firmly in place. As Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach warned Congress in 1965: “Recalcitrance and intransigence on the part of state and local officials can defeat the operation of the most unequivocal civil-rights legislation.”

President Reagan’s concern for civil rights is at best ambivalent. He has expressed only lukewarm support for the enforcement machinery in the Voting Rights Act. Moreover, he has promoted a feeling of hostility for the federal government, which tends to inhibit forceful national action. “In this present crisis,” he said in his inaugural address, “government is not the solution to our problem. Government is the problem.” Yet under the shield of the government, black voter registration soared from 2,164,200 in 1964 to 4,254,000 in 1980.

The struggle for political equality today involves fighting subtle techniques like racial gerrymandering and vote-diluting multi-member districting. The fires of white supremacy have been dampened but not extinguished. The literacy test may be confined to the dustbin of history, but it will take a continuing commitment from the federal government and the vigilance of an aroused public to keep other, equally racist techniques from taking its place.

* Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee, Texas and West Virginia did not have literacy tests.

** Under a grandfather clause, people could vote whose grandfathers were allowed to vote. Obviously, many white men and no blacks could qualify.

Tags

James J. Horgan

James J. Horgan teaches history at Saint Leo College in Florida. He was the UFW’s national director of research in 1972-73. (1983)

Dr. James J. Horgan is a professor of history at Saint Leo College in Florida. (1982)