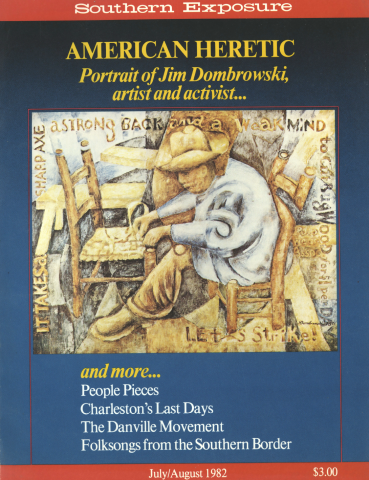

Dombrowski: Portrait of an American Heretic

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 4, "American Heretic: Portrait of Jim Dombrowski, artist and activist." Find more from that issue here.

For nearly five decades, in the minds of many established Southerners and to their ears, the name James A. Dombrowski has been an offensive intrusion, synonymous with unchecked union organizing, or worse, race mixing. A United States senator once denounced him as "the South's No. 1 enemy." Lesser public figures offered coarser descriptions.

Police arrested him in Elizabethton, Tennessee, in 1929, during the great wave of strikes in textile mills which then swirled across the South; he was jailed on the false charges of having been party to the murder of the chief of police in Gastonia, North Carolina, a town itself torn by a violent strike. In 1935, American Legionnaires and Chattanooga police chased him and a handful of other union sympathizers out of the city. Police in Birmingham, Alabama, arrested him in 1948 for violating Jim Crow laws when he spoke in an all-black church. Agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation watched his comings and goings for years. The U.S. Senate Internal Security Subcommittee subpoenaed Dombrowski for questioning in 1954.

On October 4, 1963, New Orleans police — their pistols drawn, and with impunity born of the feeling they were ridding the city of the infamous Dombrowski — arrested him for "remaining in Louisiana five consecutive days without registering with the Department of Public Safety;" for "participating in the management of a subversive organization;" and, finally, for "being a member of a Communist front organization." The police action, prompted by a study by State Representative James H. Pfister's Joint Committee on Un-American Activities of "radical agitation in Louisiana," forever etched the name Dombrowski in the history of American jurisprudence, giving citizens a bulwark — Dombrowski v. Pfister — against unwarranted governmental repression of the First Amendment's guarantees, and added the phrase "chilling effect" to the realm's common language.

Who is James A. Dombrowski? Today, he continues to live in New Orleans where, at 85 and slowed by crippling arthritis, he exerts himself in the cause which has occupied his adult life: establishing the Kingdom of God on Earth — a phrase he first heard in Tampa, Florida, where he was born on January 17, 1897. The phrase, and the meaning he came to attach to it, have been the source of his disquieting effect on the Establishment.

Dombrowski still believes what he told an astonished Chamber of Commerce meeting in strike-bound Elizabethton back in 1929: men and women are capable of seriously applying the ethical teachings of Jesus to rationally order society to eliminate want and racial division, or exploitation by sex. These same teachings could be applied to industry, he told the Chamber leaders, adding there was hope that the South, known for its gentler ways of living, would pioneer the spiritualizing of industry.

Dombrowski was among a handful of Southerners, many of them trained theologians as was he, who as they looked at the South in the economically beleaguered 1920s and 1930s envisioned how the teachings of Jesus and Karl Marx were needed to abolish poverty; to recognize the rights of workers, black and white, man and woman, to an equal share of the region's wealth; and to forever eliminate the economics of scarcity. Dombrowski is both a Christian and a Socialist; he believes that capitalism is organized social injustice, and, further, that it is the duty of a religious person to destroy capitalism without regard for his or her own personal welfare. Acting on such beliefs made Dombrowski a clear and present danger.

There were no outward hints such ideas were forming in his mind as he grew up. His mother and father, the children of immigrants, enjoyed prosperity in Tampa's middle class. Jimmy, as their son was called, graduated from high school with honors, enlisted in the Aero Service and served in France. Upon discharge, he enrolled at Emory University, where he helped found Sigma Chi fraternity and managed the Glee Club, while earning sufficient academic standing to graduate cum laude. For three years, he was the school's first alumni secretary. Then he began a peripatetic journey through higher education, first studying at Berkeley, then Harvard and finally Columbia and Union Theological Seminary.

On February 8, 1929, W. Aiken Smart, a professor of theology at Emory, sent a letter of recommendation on behalf of Dombrowski to Henry Sloane Coffin, Union's president. Smart described the Floridian as "a man of really unusual ability in many directions. His administrative and executive gifts are the greatest that I have ever seen in a college student, and if he can find the phase of religious work for which he is best adapted, I believe he will accomplish great things."

Hardly four months later, the Associated Press moved this report on its wires:

JOHNSON CITY, Tenn — (AP) — James A. Dombrowski, alleged Communist leader, was arrested near Elizabethton late Tuesday and is being held for Gastonia, N.C., officers in connection with the fatal shooting of the chief of police of Gastonia.

Hunter Bell, city editor of the Atlanta Journal, stared incredulously at the copy. He'd gone to Emory with a James A. Dombrowski, and toured Europe with him and the university's Glee Club. "There can't be but one James A. Dombrowski," he thought. "It's got to be Jimmy Dom." Other friends in Atlanta were dumbfounded when they read the news report. So were his sisters in Tampa, where the dispatch made page one. His sister, Rose, telephoned the city editor who'd printed the story, knowing he'd gone to high school with her brother. "Aren't you ashamed to print such a thing?" she scolded. "You know Jim. You know he couldn't commit a murder."

"Well," he retorted, "it is news. Some people lead double lives."

Dombrowski spent only one night in Elizabethton's foul-smelling jail. No formal charges were lodged against him, so he continued the journey he'd started through the South. The next stop was Gastonia, where he hoped he'd learn more firsthand about the ethical reasons that the strikes were sparking from milltown to milltown. Dombrowski had found "the phase of religious work for which he [was] best adapted."

By 1933, when he was 36, Dombrowski finished up his academic career. Union awarded him a bachelor of divinity degree magna cum laude. His dissertation for Columbia, The Early Days of Christian Socialism in America, was published to some acclaim. He left New York City to teach at the Highlander Folk School and to raise funds for its work. There he would soon come to be called "the Skipper" by a staff who delegated to him most administrative chores. He taught courses in economics and how to publish newspapers and organize strikes. He spent months interviewing miners, their wives and children, and others who had joined in the coal field rebellions in East Tennessee, where Highlander was located, and then used those interviews in his classes.

When hard-pressed adults began to take action on Highlander's teaching of the history and means of organized struggle, other citizens became riled. The Grundy County Crusaders formed to run Highlander out of their midst. Their efforts climaxed during a tense meeting at the University of the South, near Monteagle, between the Crusaders and Highlander's small staff. An FBI agent present reported that "only Dombrowski's skill as an orator" thwarted the Crusaders' drive. He left Highlander in 1942, persuaded by Dr. Frank Porter Graham, president of the University of North Carolina and then head of the Southern Conference on Human Welfare, that his skills as an administrator and fund-raiser were needed to shore up that faltering regional interracial organization. Dombrowski accepted the thankless job for reasons which he shared in a letter to his political confidante and friend, Alabama activist Virginia Durr: "First, it is a purely defensive action against . . . Southern reactionaries who are seeking to take advantage of the emergency [World War II] to push anti-labor bills through Congress; second, it is the only occasion when whites and Negroes get together in the South on a progressive program, and the opportunities for progress on the race issue at the moment are enormous; third, to assure labor's maximum participation in the productive efforts of the war and in the peace settlement, the unorganized South is our greatest weakness."

For a spell, Dombrowski's energies managed to keep the Southern Conference's agenda on the minds of regional and national political leaders. Wartime production needs were used as a vehicle to promote the hiring of black workers in segregated industries. A police riot in Columbia, Tennessee, left the all-black Mink Slide neighborhood a shambles, several blacks dead, and 26 others charged with an assortment of crimes which could have landed them either in the hands of a mob or the electric chair. Dombrowski's exposure of the role the police, the Tennessee Highway Patrol and the National Guard had played in the devastation led to renewed national demands for an end to lynching. But by the war's end, short of funds, bleeding internally from rival factions, and with a major political backer, Franklin D. Roosevelt, dead, the Southern Conference took the first steps towards its own eventual self-destruction by ousting Dombrowski in a bitter manner.

Personally hurt by the decision, but undaunted, Dombrowski took charge of the Southern Conference Education Fund, a SCHW offshoot, and its publication, The Southern Patriot. He turned that tiny organization's attention and its publication's pages to a single issue: the economic costs of racism. Through The Southern Patriot, Dombrowski exposed the human costs resulting from segregation in hospitals, the region's universities, colleges and law schools, in public schools, and even at such commonplaces as Coca-Cola drink dispensers which, at the time, sported water fountains — one on each side for blacks and for whites.

SCEF was always a biracial organization. So it was always small, always changing staff, who were always underpaid. They managed to organize countless conferences on racism's many topics and issues. These usually resulted in angry local protests in the communities in which they were held, and sometimes a few contributions or converts.

In March, 1954, Dombrowski faced further tribulation. Senator James O. Eastland organized hearings of the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee in New Orleans to investigate SCEF. Four members of the organization's board were summoned: Aubrey Williams, Virginia Durr, Myles Horton and Dombrowski. Eastland told the press he wanted to know if "Communists were masquerading behind the facade of a humanitarian educational institution."

From the outset the hearings were stormy. Horton was dragged from the courtroom when he tried to read a prepared statement. One of the committee's paid informants, Paul Crouch, testified, "Mrs. Virginia Foster Durr, Justice [Hugo] Black's sister-in-law, had full knowledge of the Communist conspiracy and its works when she allegedly persuaded Black to address the organizational meeting of the Conference in Birmingham in 1938." Her husband became enraged. Shouting he'd kill the witness, he lunged toward Crouch and collapsed, suffering a heart attack.

Of Dombrowski, Eastland wanted to know "who contributed to SCEF." Dombrowski refused to say, despite threats that he would be held in contempt. Failing to change Dombrowski's mind, Eastland changed course, asking if the witness belonged to any organizations which were not on the attorney general's list of subversive groups. Dombrowski named Sigma Chi at Emory, the Willard Straight Post of the American Legion in New York City, the Methodist Church and the National Council on Religion in Higher Education.

The hearings failed to quash SCEF's interracial work. On October 4, 1963, Dombrowski welcomed to New Orleans Southern lawyers, both black and white, who'd been supportive of the Civil Rights Movement and SCEF. His group and the National Lawyers Guild called the conference to outline a program of legal assistance for civil-rights workers. After opening the meeting, Dombrowski returned to his office to complete some urgent work. Suddenly, police axed open the door to his office and held him at gunpoint for three hours while uniformed city jail inmates boxed up the organization's records, then loaded them and all SCEF's furniture into trucks which left for an undisclosed destination.

Dombrowski was taken to the First Police Precinct where he was booked for violating the Louisiana Subversive Activities Control Act. He and the lawyers he gathered to defend him, including Arthur Kinoy and William Kunstler, decided to challenge the previously unassailable constitutional doctrine of abstention, the legal practice which forced citizens to exhaust all state court remedies for violations of their constitutional guarantees before turning to federal judges. Southern authorities had been using the doctrine to frustrate civil-rights activists, tying up money and energy in lengthy court proceedings.

On April 26, 1965, after months of suspense, fund-raising and frustration, Justice William Brennan, delivering a five-to-two decision, read the U.S. Supreme Court's verdict: "Freedom of expression is of transcendent value to all society . . . and substantial loss ... of freedom of expression result ... if appellants must await the state court's disposition and ultimate review." Therefore, the court concluded, the doctrine of abstention was unconstitutional because of "the chilling effect upon the exercise of First Amendment rights."

Dombrowski, a shy, private man who spurned the public limelight despite his controversial if not legendary life's story, gave his name to the nation's legal history.

Tags

Frank Adams

Frank Adams is author of Unearthing Seeds of Fire: The Idea of Highlander, a teacher and long-time friend of the Institute for Southern Studies. He is writing a biography of Jim Dombrowski. (1982)

Frank Adams interviewed Mrs. McEwin while traveling through the South for the Institute for Southern Studies’ syndicated column, Facing South. (1979)