This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 2, "Stepping Stones." Find more from that issue here.

Elizabeth Cousins Rogers and her late husband, Walter “Rog” Rogers, began leafleting together 42 years ago. Elizabeth was a self-proclaimed “East Coast bourgeois,” Smith College graduate (class of 1913) and ex-Vogue editor. Rog was the son of Lithuanian peasant immigrants, a World War I veteran, hobo, member of the IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) and ex-con (he spent a year in Alcatraz because he deserted the Army in 1919 rather than serve as a strikebreaker against miners). They met at Commonwealth College in Mena, Arkansas. Leftwing Commonwealth’s curriculum was oriented to the politics of labor and union organizing, and sponsorship by a union was a criterion for admittance. Elizabeth was teaching a course in labor journalism when Rog arrived at Commonwealth “in a dirty leather jacket, with his pockets overflowing with labor pamphlets.” As she says, “When I married him, it was just like a flame to a piece of brush. He was the flame and I was the brush.”

When Commonwealth was forced to close in 1940, “I said to Rog, ‘Well, where are we going?’ and he said, ‘We’ll go to the toughest place we can find - the Deep South!’”

The Rogerses ended up in New Orleans and over the decades they’ve written leaflets on a myriad of issues — local, national and international — meeting their goal of one a month. Their most sustained and visible effort was a six-year peace vigil in Jackson Square in the French Quarter. Each Sunday from 1970 to 1976 they handed out a new leaflet denouncing the Vietnam War.

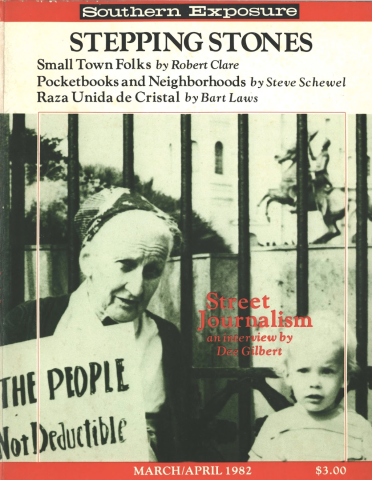

Alone now, Elizabeth, “90 years old and still wearing blue jeans,” talks about those years and about the work of their lifetime, which they dubbed “street journalism.”

Elizabeth Cousins Rogers

Journalism is a lot more than just putting out a paper. Most people think of journalism as daily newspapers. Well, the daily newspapers are not journalism, they are ad stuff. For years and years and years, all their money has come from the ads. The nickel you pay wouldn’t buy the print for one edition; we’ve known that for ages. That isn’t journalism. Journalism is what the people get about their daily lives! So there had to be a substitute, and it just grew out of the picket lines, and then it grew out of the peace movement. We started calling our leafleting “street journalism” because it is in place of the commercial newspapers, which pervert and lie.

When we first started doing street journalism, in the ’40s, we wrote leaflets on union issues — protesting union race discrimination was one of the first ones we did, I believe. See, Rog had a tremendous belief in the written word. He used to remember the Wobblies — Industrial Workers of the World — with whom he had become militant. He kept talking about the little five-cent pamphlets that they had. He said, “That is the way to reach the masses.” And nobody much listened to him, because the unions got their own stuff out and it was mostly pretty dull and dry. And some of the things that were gotten out by militants in New York didn’t fit the South at all, you see.

So we were trying to take what we knew about unions and progress and good political ideas, and put them on paper in a form that you could pass from hand to hand in the language that people speak here. You know, there are certain little New Orleans tricks that people don’t realize they are using, but they love them, and if something comes to them in that medium, they’ll think about it. You know, like “I carry my sister to the hospital” or “I been knowing you a long time.” There’s a hundred little things like that, instead of what is almost the jargon of the political writers. You know, they use words that just simply don’t have any meaning at all here. Well, we started writing and pasting up our own leaflets. We’d get items from foreign papers, we’d get them from the Daily World, we’d write a little piece of our own. And we always gave the credit to the place we got it from, no matter how far left it was. Because that’s good journalism; if you’re going to crib things and not tell, too, you’re not enhancing the truth at all.

We had, say, $60 or $70 that we could spend on printing the leaflets, and that’s about what it costs to get a run of a hundred. We never had any big financial backlog, but Rog made a good union salary then, and he never spent one cent on himself. He never played pinball, he never went around for drinks with the fellows afterwards, and I just had to beg him to get a pair of new shoes.

We had one great big room on the front of our house. We had our big mimeographing machine in there, we had piles and piles of paper, we had a book lending library, and we had, really, a little factory here where we’d get out little booklets. And we’d lay them out from one end of the room to the other - that always pleased Rog. He’d say, “Well, we’ve got a belt-line now!”

You know, if two people can go on a march with picket signs or leaflets, it’s far better than one that goes and smashes something. You’ve got to get attention, but if you can get attention in a way that you’ve reasoned, then you’ll appeal to the reasoning people too. And then you’re on the way to getting somewhere.

When asked when it was that she first began to oppose the Vietnam War, Elizabeth states flatly, “1918.” I laughed, but she did not.

Well, the feeling about Vietnam began in World War I and went on with World War II — you’ve got old-timers here, you know! Well, it builds up and builds up and you’ve got a missile there that’s just ready to pop off. World War I wasn’t over until we were in World War II and World War II wasn’t over until we began to fight with the Soviet Union.

It’s not rational, it’s not reasonable, to hate everybody because some people who are there do wrong. We are so paranoid, what we see when we look out is our own face. The minute we look across the Atlantic, we see our nasty selves looking back and we say, “That’s the Russians!”

You see, my whole life lies right along the most awful behavior of the United States. When I was eight, in 1898, Dewey took Manila. We got Cuba, we got the Philippines. They made a great deal of this. My family went to the parade, the Dewey parade, and I couldn’t go and I pulled up my grandmother’s tulips. But not because of anything political, because I thought that parade was something I wanted to go to. It was something I should have been glad to stay away from! It was the beginning of our aggression.

So we were leery about the entrance to Vietnam in the first place. We’ve seen aggression too much not to know that this was an aggressive country in an aggressive mood. They’d managed to get most of the people into that mood and it’s still flaming now. Now we’re in a position where there isn’t a single struggling revolution anywhere in the world that we aren’t actually opposing by giving supplies to the tyrants. And thumbing ourselves as if we were some sort of angels for doing it!

One of the things that really helped us in the work on Vietnam was an organization called Another Mother for Peace. They put out a folder which had a map of that whole peninsula of Southeast Asia, and they had the different companies which had bought claims in the oil deposits around there. That’s what that war was. The Vietnam War was fought by the authorities for the grabbing of the monies, as well as the repression of Communism. I’m saying that it was fought, as all wars have been, for the control of the resources. Ideology doesn’t bother the people in this country who rule it. What they’re thinking about is minerals and products and being able to overcharge for what they sell. They’re not fighting for principles, they bring the principles up and get the people excited about the principles — what they’re after is loot!

In 1969 there were busloads from Loyola and Tulane that went to Washington, and we went along with them. It really was a thing! We enjoyed every minute of it. There was a tremendous outpouring against the war, and Washington was filled from one end to the other.

We got gassed while we were in Washington, too. But it was an experience that everybody should go through; as long as people are going to be gassed for doing the right thing, it’s a good thing to spread it around, over the older people and everybody so they can see from their own experience that tear gas is not something you just shrug off. You feel as if you’re going to die, you can’t breathe, can’t breathe, eyes tearing all over. And there’s nothing you can do about it — nothing, nothing.

After the march on Washington, the university students began holding weekly peace vigils in Jackson Square. We went down and joined them, and then after awhile, the students all dropped out. All dropped out but one, who came every Sunday and, ah, we sort of thought he was keeping an eye on us. Well, when we took it over, we went into that square by that circular fountain in front of the St. Louis Cathedral, just inside the gates, and we hung our big signs on the fence and we had a lot of leaflets to put out.

A cop came round once — just a big — what Rog used to call a “Dis ’n Dat Cop.” He asked us, he said, “Do you have a permit to do this?” and Rog up and says, “Yes, indeed — the First Amendment to the United States Constitution!” And the cop kind of reddened and walked off. Never bothered us again.

We had the leaflets in big buckets we’d make out of a box, because the leaflets we didn’t give out one week, we’d use the next week. So we got about five different kinds of leaflets at a time and we’d temper them according to what the person looked like.

Sometimes people would say, “I don’t want that shit.” You get a lot of negatives. But then you just laugh and go on.

I would always station myself near a trash can, and they’d drop them in the trash and I’d get them out. Sometimes I’d get them out four or five times. “Now that’s a good leaflet,” I’d say, “went to four people!”

Now the best bets were the tourist buses, because they’d come from all over the United States. If the tour leader sees you, you can’t get anywhere. But you let that tour leader go by, and if the first one grabs it, they’ll all take it! And they stuff it away, and on the bus they’ll read it and discuss it. And that’s what we want. They’ll argue and fuss. No matter what they say, they’re bringing out what they think of it and that’s what you want. It’s the fact that you can get it to them when they’re ready and relaxed and with others that they can match their opinions against, that’s where the thing germinates, like scratching a match.

I also asked Elizabeth to describe her feeling about how the war and her work in it ended.

I don’t think that war has ever ended. They are still picking on Cambodia, they are still harassing the Vietnamese — look at all the mess they made about the refugees. It was a “crawl out” in Vietnam.

It was those young men who refused to fight that ended the war. It was mutiny, it was individual mutinies piled up by the hundreds, really thousands.

The ones that wouldn’t fight — those were the heroes of that war. That was the victory. And that was the first sign in a long time that the American people were becoming conscious of their own power. And they didn’t do it as consciousness of power, they did it in answer to their individual consciences.

The power comes from the people, and when you get a person sufficiently oppressed, they’re going to rise. It’s just like you put a kettle on the fire and put an airtight cover on it and flame underneath — after awhile it’s going to explode, and it’s going to have an effect.

Well so, that’s what we did during the Vietnam War, our leaflets. They were very successful. We got rid of all of them, always kept about 25 in a file. Every once in awhile I try to sit down to organize that file, but I’ve got involved with local work and daily work, which is the most important because we’re hanging by a thread now. Anyone that you can influence or anything that you can do to throw a little light on the situation, you must do now, because if we don’t do it now we may not be here!

Young folks, the gains we’ve made

we pass to you;

As old folks, we’ve done the best

that we could do.

There are battles ahead... to win!

Just remember, as you begin

Working people are all one kin!

- Elizabeth Cousins Rogers

Tags

Dee Gilbert

Dee Gilbert is a free-lance writer living in New Orleans, and the director of Patchwork — An Oral History Project. (1983)

Dee Gilbert is a New Orleans free-lance writer and coordinator of the New Orleans Women’s Oral History Project. (1982)