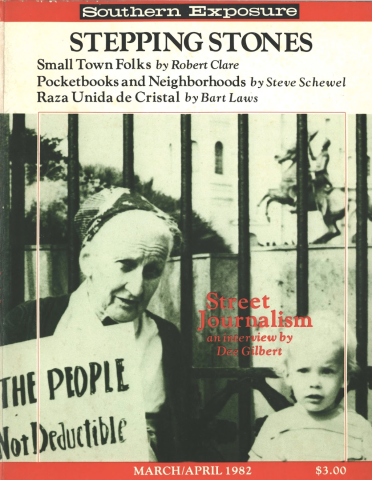

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 2, "Stepping Stones." Find more from that issue here.

On December 8, 1980, Cecil Walker of Meridian, Mississippi, went out to cut and haul a load of pulpwood. At 6:30 in the morning, he departed from the Kemper County woods 30 miles north of the city. He was driving his ’57 Ford truck, rebuilt with four posts welded onto the back two thirds of his chassis in order to hold the four cords of five-foot-three-inch pine logs he was about to cut. Cecil was anxious to get working that day since he had spent the past week and a half repairing his truck’s engine and scraping together the money to cover the parts. His bills were running late, Christmas was coming, and Cecil needed the $70 that each load of wood would earn him.

Usually, a pulpwood cutter goes out with a crew of two to four other people. It’s not uncommon to find family members, often the cutter’s children in their early teens, serving as helpers. Once the tree has been cut with their hand-held, gasoline-driven chainsaws, the cutter and his crew begin the arduous task of loading it. With the help of a boom that swings a metal cable over the side of the truck, the wood is hoisted and stacked onto the truck, often towering 20 feet off the ground. On December 8, however, Cecil was performing the task alone. Six hours later, with his truck stacked, his clothes covered with saw dust and the buzz of his chainsaw ringing in his ears, Cecil left the woods for the long and winding drive down Highway 45 back to the Meridian woodyard.

Cecil was a big man, about 30 pounds overweight. He was missing one arm from the elbow down, the result of a chainsaw accident incurred four years earlier. His friends say that it’s no wonder he was unsuccessful in bailing out when his brakes gave way and his speeding truck crushed him against the wooden embankment, killing him instantly. On December 8, Cecil Walker became the third United Woodcutters Association (UWA) member in five weeks to be killed or permanently disabled because he cut pulpwood for a living.

Who Are The Woodcutters?

Pulpwood cutters are as important to the paper industry as farmers are to the production of food, or assembly line workers are to the manufacturing of automobiles and steel, or textile workers are to the manufacturing of clothing and linen products; and yet, the majority of pulpwood cutters lack basic employee protections such as worker’s compensation, disability insurance, social security, unemployment insurance and retirement benefits. High operating costs and exaggerated suffering caused by the spiraling cost of living have thrown many woodcutters into a cycle of economic debt and dependency. They suffer from a rate of accidents and fatalities second only to mine workers in this country. And woodcutters are unprotected by any legal remedies to the problem of “shortsticking”: the mismeasurement of the wood they sell, accounting for heavy economic losses.

The majority of Mississippi’s 10,000 pulpwood cutters are black, living off dirt roads in pocket rural communities outside the nearby towns and villages. Their lives and their jobs closely resemble those of their sharecropping forefathers. When we asked one UWA member what his father did for a living he responded, “farming.” When we asked him what and where he farmed, he replied, “You know, sharecropping. He worked for Joe Riley. I’m cutting wood off his son’s land now.”

The woodcutter is responsible for supplying all of the equipment necessary to get the job done. This includes his truck, chainsaw and the replacement parts and many gallons of gasoline needed to keep them running. Out of his paycheck also comes the stumpage fee: money paid to the landowner for timber. To get himself started and keep himself in business, the woodcutter often borrows money from the local woodyard operator. It’s not uncommon to see payments for a truck, a chainsaw and even mortgage payments on the cutter’s house under the deduction column on his paycheck. And the interest rates are often exorbitant. One cutter told me, “I borrowed $1,400 about four years ago to replace the engine in my truck, fix my pickup and buy a new chainsaw. He’s been taking five to 10 dollars out of every load I haul. About a year ago I asked him how much I still owed. After he checked his books he told me — $1,400.”

The Woodyards And The Paper Companies

After a pulpwood cutter has spent a long day in the woods, cutting pine or hardwood with his chainsaw into five-foot-three-inch lengths and stacking the wood on his rig, he delivers the wood to one of the approximately 200 pulpwood receiving facilities, (woodyards) in the state. It is the woodyard operator who measures and purchases the wood from the cutter and in turn ships it by truck or train on to the pulp mill where the wood will be manufactured into paper, particleboard, cardboard and a host of other products.

It is the woodyard operator with whom the pulpwood cutter has daily contact. Although the price paid for a cord of wood has increased only about 20 percent over the past 10 years, the woodcutter’s operating costs (and profits of the paper companies) have soared 300 to 400 percent. As the woodyard operators have continued to shortstick in the measurement of a cutter’s wood, woodcutters’ anger has naturally focused on this most immediate culprit, the woodyard owner and operator. The woodyard operator is, in fact, a convenient middleman serving the interests of himself and the paper companies. The term middleman or “labor contractor” — a person who makes a deal with a firm to supply a certain product and in turn supervises and coordinates the labor involved in getting that product — is the most accurate description for the woodyard operators.

Almost all of the 200 woodyards operating in Mississippi are capitalized by one of the major paper companies. Operating and owning a woodyard is an expensive venture. Initial investment capital is required for the land where the yard is situated, loaders which move the wood off the trucks and onto the train cars and trucks, and to buy wood before it is shipped off and sold to the paper companies. Capital is also required to hire a couple of yard operators and to loan money to the cutters to buy saws, trucks and other equipment. In return, the paper companies receive a long-term, first-refusal contract with the woodyard. It is believed that the paper companies set quotas on how much wood and the type of wood bought by the yards on a per week basis. They also set the price per cord.

The following hypothetical example illustrates this dependency of the woodyard on the paper companies. St. Regis capitalizes a local woodyard in return for 200 to 500 cords of wood per week. If a woodyard buys more wood than the week’s quota, they are free to sell it elsewhere. St. Regis normally buys the wood for $400 per train car load, but announces for the next few weeks that the demand is low and that they will only pay $375. The woodyard operator is then in a position of taking the loss himself, cutting back on the price per cord he pays the cutter or under-estimating the amount of wood the cutter has delivered (shortsticking). The wooddealer is caught, having very little control over the situation. An excellent real example of this dependency occurred this past summer when a Crown Zellerbach mill was partially destroyed by fire and all of the yards supplying the mill were forced to cut back drastically or completely shut down.

Who are the wooddealers? In general, they are the prominent businesspeople in the small Mississippi communities where the yards are located. They may own the local hardware store, saw shop or, as in the case of Bennie Garner of Mendenhaul, Mississippi, the local Ford and Tractor dealership. There are also individuals who do nothing else but own and operate several yards in an area. Richton Tie & Timber, based in Perry County, owns 17 woodyards throughout Mississippi.

The major ramification of this system for the woodcutter is the lack of basic employee protections and benefits. By law the woodcutter is considered an independent business-person. This permits the paper companies to avoid having to contract directly with the woodcutters and provide any benefits. Whether by calculated intent or sheer neglect, the woodyard system serves the financial interests of the paper companies.

PAPER COMPANY PROFILES

The major paper companies operating in Mississippi are International, Weyerhauser, St. Regis, Masonite, Crown Zellerbach and Georgia Pacific. They are all billion dollar companies, listed in the “Fortune 500,” operating pulp mills and owning extensive land holdings throughout the South. All are multinationals and conglomerates.

In the late 1950s and early ’60s, they began a program of worldwide expansion. All have investments in at least two of the three underdeveloped forest regions in the noncommunist world: North America, the Amazon region of Brazil and the Philippines. A number of them also have economic holdings in South Africa.

In the middle ’60s each company began a pattern of diversification and conglomeration, investing in profitable areas such as land holdings, oil and natural gas, chemicals, plastics, etc. Because of their vast land holdings, they are able to drill and explore on this land for oil and natural gas. While many of them contract with the oil companies to do research and development and thereby receive royalties with high profit margins, International Paper Company and Georgia Pacific have purchased their own oil companies.

In the area of chemical production, the companies have had their foot in the door from the start since a wide range of chemicals are needed in the production of paper. But in recent years, the companies have shifted from ownership and production of chemicals for their own use to sales on the open market. In 1960 chemical firms owned by Georgia Pacific sold 80 percent of their production to their own pulp mills, whereas today 85 percent is sold on the open market.

Besides being multinational and conglomerate in scope, the paper companies and paper industry are highly concentrated. Whereas a lumber yard and mill are small ventures, needing a small amount of capital to get started, pulp mills are expensive, highly mechanized operations requiring 24-hour-a-day operation at 95 percent capacity to register profits. The five largest paper companies account for over 33 percent of the Southern pulp producing capacity, with the top 10 accounting for 48.9 percent.

The timber industry needs the South and the South needs the timber industry. The South supplies 45 percent of the country’s forest products, including paper, lumber and building products. In 1970, timber companies owned over 2.5 million acres of land in Mississippi alone; they are continually buying up and long-term leasing poor people’s small land holdings. There are five major pulp mills in Mississippi and plans for at least three more in the near future. The superstructure of rail lines to and from the woodyards and pulp mills, along with a trained work force and vast forest regions, means that the companies are in the South to stay.

The state of Mississippi needs the timber industry as much as the industry needs Mississippi. One out of every four dollars in the Mississippi economy comes from the manufacturing and sale of forest products. It is estimated that beyond the 10,000 pulpwood cutters in the state there are 7,000 jobs in the paper industry, 18,000 jobs in the furniture industry and 23,000 jobs in lumber and wood products.

There are many reasons why Mississippi and the South provide a favorable business climate to the timber and paper industry. Trees simply grow more rapidly in the South’s warm and damp climate. Whereas the Douglas Fir of the Pacific Northwest requires 65 to 75 years to grow and mature, the Southern Pine requires only 30 years. With the recent boom of the Sunbelt economy, greater demand for paper, construction and other wood materials provides for expanding markets. European markets are also expanding as Scandinavian wood production has reached its output capacity.

In the Pacific Northwest the public sector owns extensive forest lands, but in the South only nine percent of the forests are not in the hands of private owners. Low taxes, low wages, strong “right-to-work” laws (in Mississippi, these statutes are built into the state constitution), and very few conservation restrictions are further reasons why the paper and timber industries are happy to return to their Southern roots.

The Woodcutters Organize

Legend has it that two friends were walking along the road, one of whom bragged about his talent with a bullwhip. Growing tired of this boasting, his friend finally challenged him. “If you’re so good with that thing, let me see you knock just one leaf off that tree.” With a flash, one crack of the whip had the leaf floating to the ground. After further walking and bragging, his friend challenged him again. “If you’re so good, let’s see you knock one petal off that flower.” Sure enough, done as before. Finally, the companions approached a beehive hanging from a tree. “See those bees flying around that hive? If you’re really as good as you say you are, let’s see you hit just one of them bees.” Our friend with the bullwhip stopped in his tracks, turned to his friend and quickly exclaimed, “Are you kidding! Bees are organized! You knock one of them bees off that hive and the whole herd will be after us!”

If we have learned anything from the gains made by auto and steel workers in the ’30s, the Civil Rights Movement in the ’50s and ’60s and the organizing of farmworkers in the ’60s and 70s, it’s the lesson that alone and divided we shall fall, but organized and together we shall win. Solid organization is the key to the United Woodcutters Association’s strategy for improving working conditions for Southern woodcutters.

Woodcutters have been trying to improve working conditions for as long as they have been cutting wood. At the turn of the century, the Industrial Workers of the World helped Louisiana woodcutters to organize. But as severe government repression crushed the Wobblies, so too did it destroy the efforts of the woodcutters. In the early 70s the Southern Conference Education Fund (SCEF) provided substantial support for an organizing drive among woodcutters. But when political infighting destroyed SCEF, the woodcutters’ organizing fell victim as well.

If there is a lesson in this history, it is that the nature and extent of community support for poor people who organize is critical. Given the importance of the church in the rural South, the United Woodcutters Association has placed a priority on building support in the religious community. Begun in 1978 and sustained by the funding and support of major national and local religious denominations, the Southern Woodcutters Assistance Project provides support and technical assistance to the organizing of Southern pulpwood cutters.

Project director Reverend Jim Drake brought 16 years of experience with the California United Farmworkers Union to this project. Using organizing styles and tactics developed by Fred Ross, Saul Alinsky, the Industrial Areas Foundation, Cesar Chavez and the UFW, woodcutters have been organized into locally based UWA coops and credit unions across the state.

The United Woodcutters Association is the official workers organization with members in 43 of the largest wood-producing counties in the state. Upon becoming a UWA member and paying his $36 a year dues, a woodcutter can purchase his oil and chainsaw replacement parts at about half the retail cost from a fellow member who serves as the coop representative. The reps collect dues and sell the parts out of their houses, which are restocked once every two weeks. Coop sales for 1981 were $112,000.

The United Woodcutters Federal Credit Union was begun in 1980 as a means of breaking the dependency and credit trap woodcutters find themselves in with the woodyard operators. Members of the credit union make regular contributions, apply for loans of up to $500 to their local credit union committee consisting of their fellow woodcutters and wives, repay the loans at low interest rates and share in the year-end profits that the credit union has accumulated. All initial loan decisions are made by local credit committees representing both woodcutters and their wives. Twenty-five percent of the elected officers of the credit union are women.

Besides providing substantial economic savings, the coop and credit union have allowed woodcutters to work together and trust one another. By building stable institutions in the local communities, organizers have been freed to move into new counties, building a statewide organization.

Fair Scale

Currently the UWA has over 1,200 members. Six-hundred-and-fifty people attended the August, 1980, Second Annual Convention. There the UWA voted that its first campaign would be to end the “shortstick.”

When a woodcutter takes a loaded pulpwood truck to a woodyard, the woodyard operator measures the amount of wood for sale with a calibrated stick. Using the height, width and length measurements, the dealer figures the number of cords for which a cutter will be paid on a conversion table. Inaccurate measuring causes cutters to lose, on an average, between $2,000 and $5,000 a year.

The lack of legislative protection against shortsticking has led the woodcutters into a campaign to get the Mississippi legislature to pass the UWA “Fair Pulpwood Scaling and Practices Act.” The purpose of the act is to set standards as to how wood is measured and to establish an arbitration board to settle grievances and issue penalties against yards found cheating on the stick or harassing haulers who file complaints.

In the fall of 1980, woodcutters held community meetings to inform their state legislators of the shortstick problem and to urge them to vote for the law. The Kemper County community meeting serves as a good example of woodcutters and their families coming together. As the cutters and their wives gathered a week prior to the meeting to plan the agenda, one of the cutters asked, “If the dealer finds out that I am passing out leaflets about this meeting, and he cuts me off, which one of you is going home with me to tell my family that I’m out of a job?” The debate and discussion which followed surfaced the fears of reprisals and intimidation that are rampant in the pulpwood industry. Six days later, despite heavy rains and the muddy access to the community center, 100 people came to present their concerns and to witness their two legislators promise to support and sponsor the act.

The UWA’s legislation was killed in the 1981 session by the active lobbying of the paper industry and the collusion of the state’s powerful legislative leadership. But the UWA continued building support for the legislative proposal.

Early in the year, representatives of five religious denominations constituted themselves as the “Mississippi Clergy and Laypeoples Committee for Woodcutter Justice.” Based on testimony gathered at a special hearing, the Committee issued press statements and testified before legislative committees in support of the woodcutters. In the fall, Bishop C.P. Minnick of the Mississippi Conference of the United Methodist Church published a statement calling for fair scaling legislation. Soon thereafter, Bishop Joseph Bru-

nini of the Jackson Diocese of the Catholic Church also issued a statement of support, as did the Central Mississippi Presbytery of the Presbyterian Church U.S.

Months of work came to fruition in November when the Mississippi Farm Bureau’s convention endorsed a call for fair scaling legislation. The UWA had long maintained that timberland owners were cheated along with the woodcutters by shortsticking. A groundswell of concern by the state’s small timberland owners moved the generally conservative Farm Bureau into action.

The UWA’s 1982 legislative campaign centered on a statewide “Truck-in for Justice” caravan. For three weeks a member of the UWA Executive Board drove the lead pulpwood truck through 20 UWA locals around the state. Each stop was an occasion for a parade, a community meeting or an action at the local woodyard. These events received extensive press coverage in county papers and on small radio stations across the state. On January 29 the caravan returned to Jackson for a parade and rally. The day when a dozen raggedy old pulpwood trucks, and 20 pickups and cars, paraded through downtown Jackson at the lunch hour will be remembered for a long time to come by the woodcutters of Mississippi.

At the time of this writing, the UWA’s proposed legislation had cleared the full House of Representatives by a vote of 111 to six and was before the Senate Agriculture Committee. [Editor’s note: The legislation passed and became the Mississippi Fair Pulpwood Scaling and Practices Act.]

The fight against shortsticking is just the beginning. Even if woodcutters were paid for the full size of their load, they would still be trapped at the bottom of the economic ladder. Victory over shortsticking would mean a significant shift in the power relationships at the woodyards. The industry’s historic ability to cheat and harass woodcutters would be severely restricted through the mediation of the state. But the fundamental issues of the price paid per cord and basic employee benefits continue to loom over the woodcutters and their families.

Fair Pay

The 1,000 people who attended the UWA’s Second Constitutional Convention in September, 1981, moved the organization forward into new

and challenging directions. Taking the lead of the courageous Fayette haulers, the convention expanded the rallying call of the association from “Fair Scale” to “Fair Scale/Fair Pay.”

During the summer of 1981, the UWA led a successful strike that brought the pulpwood business in Fayette, Mississippi, to a complete halt. Woodcutters stayed on strike for four weeks, shutting down all three yards in the Fayette area.

It was a difficult strike; even picket duty was problematic. It was too hot to leave picketers outside the yards for long shifts: 95 degrees at 10:00 in the morning and over 100 all afternoon long. A system was worked out where the gas stations were watched to be sure no woodtrucks fueled up, and patrols were sent out every half hour to check the yards and be sure no wood was being delivered. One of the strike leaders began receiving threatening phone calls at home. Another striker had his woodtruck repossessed by the yard.

But the strikers held firm, meeting daily to receive reports from the strike committee and to divide up responsibilities. Of the 51 woodcutting crews in the Fayette area, only two continued hauling through the strike. But the most noteworthy development was the support given by other woodcutters across the state. Delegations of UWA members drove hundreds of miles to join the Fayette haulers in marches and on picket duty. Dozens of locals made financial contributions to the strikers.

After one month the first yard gave in. They agreed to a set of scaling regulations, which are now posted at the yard, and a raise in the price paid per cord (by giving a “bonus cord.”) They also agreed to buy wood from all the haulers in the area, regardless of where they hauled prior to the strike or how active they had been in the strike. With that settlement the worst was over. It was six more weeks until the second yard reopened with a raise on the wood.

The third yard never reopened. It was International Paper’s woodyard. Jake Morris, the dealer, had reached a tentative agreement with the haulers, but returned to say that the company forbade him from finalizing it. There is little remorse, however, for Morris was the worst dealer in the county. He was renowned for excessive cheating on the stick and for loan-sharking on haulers’ debts. The lesson is clear, though: while the independent dealers were willing to settle, International Paper — the giant of the industry — chose to take the hard line.

International Paper is the kingpin. For conditions to improve in the industry, change must start with them. Woodcutters have a long struggle ahead before they can realize the basic benefits and living wages most American workers take for granted. But with the leadership developing out of the coop, credit union, fair scaling campaign and local strikes like the one in Fayette, the United Woodcutters Association is building a strong core from which to work.

Tags

Paul Cromwell

Paul Cromwell, a student at Union Theological Seminary, spent a year and a half as an intern with the Southern Woodcutters Assistance Project. Tom Israel is Assistant to the President of the United Woodcutters Association. (1982)

Tom Israel

Tom Israel is Assistant to the President of the United Woodcutters Association. (1982)