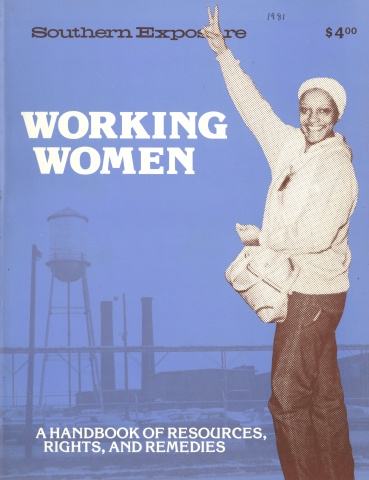

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 4, "Working Women: A Handbook of Resources, Rights, and Remedies." Find more from that issue here.

At the time the movie “Norma Rae’’ was being released across the country, a similar real-life drama was taking place in the small city of Maryville, Tennessee, just south of Knoxville. On two different days in 1979, mass walkouts were staged by 800 Levi Strauss workers — 90 percent women — members of United Garment Workers Local 402. The walkouts culminated in a five-week wildcat strike.

The strike was a victory, though a mixed one, for the employees: the supervisor who triggered the walkouts, the plant manager and the assistant manager were all transferred to other locations. But NLRB arbitration ultimately upheld Levi’s suspension of four workers and the firing of two union officials, including the president.

Norma “Corky” Jennings, who is interviewed here, is that president. In a tribute to her leadership, members of Local 402 voted overwhelmingly after the NLRB ruling to keep her as their president and to pay her the same salary she was earning at Levi’s. That agreement continues as the local looks toward contract negotiations in December, 1981.

I was born here in Blount County in 1939, and married when I was 15. My husband was in the service, so we moved around for about six or seven years, and when we separated and divorced, I brought my three boys and came back here. I went to work at Levi’s in 1963.1 had 17 years in when I got fired.

I was born in an Aluminum Company house. My father and grandfather were instrumental in organizing the Aluminum Workers at Alcoa — later the local changed to the Steelworkers. But they had such a bad experience it was very rarely discussed in our family. They felt they were sold out by some of their friends.

When I started being active as president of Local 402, my father told me they’d sell me out. He told me when I got into it, when we struck the first time, “Now if you go again, Corky, they’ll fire you, and you watch those people, they’ll drop you like a hot potato.” And of course, that didn’t happen. That’s been the good part of this: women sticking together.

In the beginning, I found it hard to talk in front of people. I hate to meet new people. I’m very self-conscious about my weight. I began to talk in front of crowds gradually.

Plant management was another thing. The plant manager told me the first time after I was elected that he’d be damned if I would run that plant. And that he had me pegged for a troublemaker and I probably wouldn’t be there long. Now, any other way he would have handled me, I probably would have been terrified of him. I wasn’t anything but damn mad after that. So, I got to where I would just talk to him like one of my kids when I wanted to chew him out. I talked to him just like he did me.

We won quite a few things. We got machines fixed, we got mechanics chewed out, we got supervisors off the girls’ backs. And pretty soon people began to expect that to happen. And gradually we built a following, because people began to see if you will open your mouth, you can get it done — and so what if people say you’re a troublemaker? If your paycheck’s right and your machine’s fixed, what difference does it make what they think of you?

The problem [leading up to the walkouts] was in one department with one supervisor. She had been moved from department to department all over the plant. They used her to keep the people down. She would be sent to a department and she would harass people there. Then the employees would get fed up, but as soon as they would get ready to fight her, the company would move her again.

Up until May [1979], she was the supervisor in the “pfaff” department. The women in the department decided to do something about her, so they filed grievances. Then she got rougher with the ones who did file. We met with the company right up till the day we walked out, but they kept backing her. The employees got up in arms that the company would back one person in the wrong against 800 people, just to show that she had the authority.

One Monday — May 7 — the officials from Levi’s regional office in Knoxville agreed to talk to all 25 of the machine operators in her department. When the operators came out of this meeting, they told us [union officials] that the company wouldn’t do anything.

So we went to the line stewards in each department. Everybody was ready, waiting. In some areas we just walked through and held up one finger, meaning one o’clock was the time. The production manager told us to stop it or somebody would be fired. I left him and walked through the room holding up one finger. I got to my department at 10 till one and waited.

At one o’clock, a few machines were turned off, and then out of the double doors from the pfaff department came 20 of the 25 women. I joined them and so did other union leaders. Behind us we could hear shuffling and machines being cut off. The sound was something. At first it was real noisy as usual, but then one machine after another shut off. It was like in waves until all over the plant it was quiet.

At first when we got outside there was only about 35 of us and I thought that was it. We would be fired. I had hoped that half of the employees would come out. But then the doors opened and the people poured out! Finally, about 800 came out.

We settled it all by Tuesday noon and returned to work Wednesday morning at 7:00.

The company took the supervisor out of the plant and put her on leave. But we were dumb. Our international said, “Go with a verbal agreement because you were illegal.” So we went back to work, and the company said that the supervisor “will never be over you in any capacity.” Now, we took “over you” literally. What they meant was she’d never be a supervisor. Well, that left her wide open for a line manager, an instructor, time-study person, you know, breathing down your neck.

So we dickered for about five weeks over this. It just finally got hotter and hotter and the people said, “Well, they’ll just show us that they’ll do as they damn well please and we’ll just walk out again.”

When the company brought a video camera in and then stopped talking to us, it snowballed that day. By lunchtime, I knew it was getting out of hand — we were fighting supervisors making remarks, line managers threatening people. The final thing was, the manager came back to me and said, “Do you think you’re gonna go?” and I said, “Yessir, I believe they are, in spite of what we can do,” and he said, “Oh, hell'' and turned around and walked away. Then he turned back and said, “Well, I’ve got this much to say to you, Corky, we did all we could do. It’s out of our hands.” And when he gestured like that [swinging his arms], some people standing in the door thought he fired me. That was 2:20. At 2:30, buddy, just as regular as clockwork, those machines went off. Eight hundred people walked out again. It was good! When the going got rough on the picket line, we’d rehash that!

And the company’s videotape! Mickey Mouse could have done better! The cameraman was going to get these “80 wild-eyed radicals” as they walked out, and they’d fire em like that. Well, 800 walked out and the cameraman is going crazy! He couldn’t cover all the doors. When they showed the film at arbitration, it was just panning from one door to another - sometimes at such speed it was just a blur.

They took me to jail [for refusing to obey an order to take down the picket line and return to work, July 11, 1979]. If I had buckled then, we’d have had a holocaust over here. We would have lost everything. I treated it as a joke. See, they put me in a cell that had a shower stall. I’m five feet, and the shower stall was over six feet. And on top of the shower stall is the toilet paper. Now there’s the commode and the shower stall and a table with benches, and it’s all concreted in the floor. I can’t reach the toilet paper! In there by myself. I finally got a jailer to come in to get the toilet paper down.

When I finally get out of jail, there’s this whole bunch of people, still kind of in a trauma. I could have rabbleroused, or cried. Instead I said, “Well, it’s nice to be out where you can reach the toilet paper.” I made fun of the situation and they picked it up. That makes a difference in what reaction you get from your people.

We went back to work the last week in July, 1979. It was hard, very hard. It was really a pressure cooker in there, because the company was really very active, saying, “You didn’t win a thing. You lost all that money and you’re never going to make it up. We’re going to get rid of this union.” They fired me for leading the people out. I told people that, why not just kill a little time and then I’ll say, “I choose not to arbitrate, I’ll just take the firing.” But they insisted that we follow it all the way through, that we’d learn from it. So they spent $21,000 on it. They raised their union dues two different times. And then [when arbitration upheld the firing] the next day we had a union meeting and they voted to pay me what Levi’s was paying me and to keep me as their president.

I don’t think you can straddle the fence. You’re either union or you’re company. I’ve had friends in management, we grew up together, we had our children together. I no longer go to their homes and they’re not welcome in mine. That was the line I drew when I made my stand and they chose management.

I think one of labor’s biggest problems is that they’ve sold themselves out to management just by getting a little closer and a little closer and a little closer. You can’t be that close to people and not make concessions. It soon gets to be more important that Joe Blow, who owns a business downtown and whom you might get a favor from, is happier with you than your members. You get to where you’re dividing your loyalties.

And local control is positive in keeping your union strong. Your people get more involved. But you do have a lot more power if you negotiate like the Steelworkers do. If you can shut down the whole steel and aluminum industry, you can do something, you’ve got some leverage. I’d love to see all the Garment Workers’ plants in Levi’s negotiate at the same time. But still each local have a say in that, absolutely.

I think primarily our local proves that women stuck together. All that hogwash about if it comes to their kids going hungry, they won’t stick is just a bunch of propaganda. Because when you get into that “Babies and Banners” thing [a film about the Women’s Emergency Brigade during the sit-down strikes in General Motors plants in 1937], those women stuck together. They never got any credit for it, but they stuck.

I don’t care how you rationalize it, somewhere in you, you think, “Look at so-and-so, she stays home with her kids eight hours a day, and she does such and such with em” — and you feel so guilty about working. But if you’ve got a job, you’ve got to do it. You have to juggle somewhere. I have looked at end products now for 20 years, and the children whose mothers participated outside the home are better behaved, more well-rounded children. They learn to cope for themselves in a lot of situations. The mothers didn’t slight them.

One of our leaders, her children in the next two or three years will be leaving home. Suddenly she’s found something she can do besides have babies and work! She really enjoys the union. And she’s been at Levi’s long enough and had her nose rubbed in it when her kids were little and she had to take it: now she really gets the satisfaction out of seeing that they don’t do it anymore. You never forget it.

One of the most touching things that has happened since the strike was what a 63-year-old woman said to me. She told me, “I’m so glad we did this before I retired. Now I can sit home and remember when we stood up to them.”

Tags

Jamie Harris

Jamie Harris is editor of the Knoxville Gazette, a monthly grassroots newspaper covering issues facing poor and working people in inner-city Knoxville, Tennessee. Brenda Bell, who lives in Blount County, Tennessee, has been on the staff of ACTWU’s Threads program for the past several years. This experimental program ended in 1981. (1981)