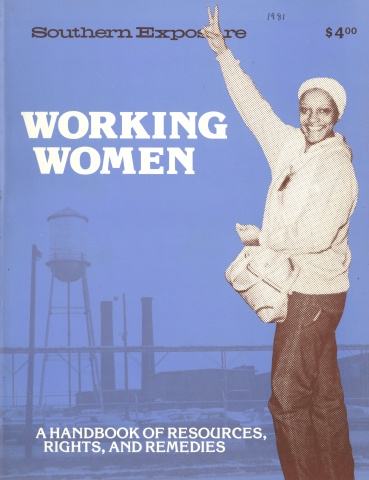

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 4, "Working Women: A Handbook of Resources, Rights, and Remedies." Find more from that issue here.

With the help of her union, a teacher learns that she is not just a professional, but also a worker with the right and responsibility to speak out in the workplace and in the community.

I was born in the South and raised in ignorance. I was taught to be a good girl and a hard worker — to be nice and polite and obedient. For years these imperatives — this cultural conditioning — worked and I walked the working-class chalk line unaware of my oppression and its true causes. Like a sleepwalker, I believed the myths about unions.

A college education only reinforced my antiunionism. This was achieved by a lack of information. I passed through the public school systems of the South without ever being taught any of the accomplishments of the great unions of America. In history and education courses, I made As without ever knowing that the unions had worked to establish child labor laws, compulsory education laws, minimum wage laws, worker’s compensation and health and safety standards. When I graduated from the University of North Carolina, I could identify the characters, the scene, the play for any line in Shakespeare’s tragedies. But I had never heard of the Triangle Shirt Factory Fire and the tragedy of hundreds of women dying because the factory was unsafe and all the doors locked. Such facts would surely have confused a good Southern worker.

On one point, the School of Education broke the silence on unions. Prospective teachers were taught in the 1960s that unions and strikes were unprofessional, but it was okay to join the North Carolina Association of Educators (NCAE). The NCAE was recognized as harmless because its non-threatening tactics of begging and complaining accomplished very little. Dominated by school administrators, the NCAE leadership still claims that it is not a union.

No beginning teacher wants to be accused of being unprofessional, so in 19701 obediently joined the NCAE, served on the Political Action Committee and was soon appointed by the principal to collect the fees from the professionals and go to the meetings. The meetings were usually conducted or controlled by the president, an assistant principal or the NCAE paid staff. Such leadership is not conducive to independent thought nor receptive to contradictory suggestions or divergent viewpoints. Business usually consisted of deciding who would be delegates to annual Atlanta conferences and how much would be spent.

One night after we had interviewed all the school board candidates and were deciding who to endorse, we were told by the NCAE staffperson that we had to endorse the incumbent because he was going to be reelected and we had to pick winners. Many of the interviewing teachers were against the endorsement because the candidate hadn’t done anything to help teachers during his previous term. Unfortunately, we endorsed him. Fortunately he lost. I began to understand why, in spite of NCAE’s 50-year existence, teachers were still oppressed and underpaid. In fact, I was beginning to feel downright unprofessional!

In fairness to this fine group of teachers who have good intentions but poor leadership, we did take a busload of teachers to Raleigh to “ask” for a raise. We had the whole Ambassador Theater full of teachers and we were mad! But we allowed ourselves to be herded into the theater and “talked to.” Picketing or marching were unprofessional. Few legislators or citizens knew we were there or cared.

In spite of these experiences, the day I received a notice that the Organizing Committee of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) was holding a union meeting, I was outraged! “How did they get my name? Who could have sent this union stuff to me? I am a professional!” I tore the notice to pieces and flushed them. I had absorbed my anti-union messages well.

I will never forget the incident that changed me from a passive, docile, compliant, uninformed professional into an active, assertive, questioning and aware trade unionist. The former personnel director for the Charlotte-Mecklenberg schools made an arbitrary decision that vocational teachers — I teach graphic arts — were not entitled to the same amount of Easter vacation time as academic teachers. We were all telephoned on Easter Monday and told that we had to report to school for the remainder of the week. We went to school. There were no students, no work to do and no heat in the buildings. We decided to form a grievance committee. Most of the vocational teachers met, and more than 100 signed a petition to file a formal grievance. I was elected as one of six teachers to handle the grievance. Then we got the screws one by one and in groups. We were intimidated by our principals, supervisors and even other teachers. Teachers who had originally supported filing a grievance came to me whispering, “Just take my name off that petition.” My own director of vocational education advised us not to “rock the boat. We may win this but they may take something else away.” I was amazed and aghast. This was our leader? What else could they take away? Where was the NCAE? A myth died that day. Nobody was taking care of things for us. We had to do it ourselves.

The grievance procedure, designed to frustrate and discourage, took from Easter until June. Before the end, all teachers except the six on the committee had been coerced into withdrawing their names from the petition. We were “unreasonable” and carried the grievance to the superintendent, and he knew that our next step was to go to the school board. We had done our homework under the direction of the chairperson of the committee, Bob Doster, who combed the books and found a law that not only gave the vocational teachers equal holidays but three additional sick days. We won the grievance and were given the last days of school off for compensation. All teachers now get eight sick days instead of five. Another myth was dead. Sometimes, you can’t be nice.

I began to wonder about other myths I had been taught. I even thought about going to a union meeting, but I didn’t want to get involved with gangsters. That myth died when an English teacher in my school said that she was a member of the AFT and thought it was the organization for me. I liked and respected her so I agreed to join. She assured me we wouldn’t get fired because the names of the members were to remain a secret until we were chartered. We wouldn’t be chartered until 200 teachers joined.

At first I was delighted to be a secret union member. Then something happened that made me so proud of the union that I wanted everyone to know I belonged to a group that would stand up and fight for the rights of teachers.

One day as the custodian was adjusting an overhead heating unit, the entire sheet metal door crashed down from the high ceiling, hitting my head and knocking me to the floor. I had a concussion and headaches for several days and missed two school days. When my paycheck came at the end of the month, $40 was missing. I had been docked two days for the substitute teacher. I went to the principal and asked him if the school board didn’t have worker’s compensation for workers hurt in the line of duty. He said that the coverage didn’t go into effect until the sixth day. Because I had come to work instead of staying home with my headache, I had to pay for the substitute teacher. “But what teacher can afford to pay $20 a day for five days?” I asked. He said that it was my problem and he couldn’t help me. I went to the phone and called my union representative. He assured me that I would get my $40 back. He said he’d make an appointment with the superintendent and publicize the fact that teachers were being denied their rights. He explained the importance of documentation. “Get it in writing” that I had suffered a pay loss for performing my duty. I wrote a letter to the principal telling him what had happened and asking him to reimburse me $40.1 memorized his reply: “Dear Mrs. Best, I am sorry to learn of your accident and will see to it that you receive a check for $40.”

I came out of the union closet, and when the AFT local was chartered in 1974 I ran for vicepresident. Since then I have served my union and plan to be a union member till I die. There are thousands of AFT members and through the central labor councils in each city and the state and national AFL-CIO, we are linked with all other union workers — parents of the children we teach.

Our local union has blossomed into the most vocal, visible and respected voice of Charlotte teachers. We have helped elect school board members who have changed the climate of the board room. Our presentations to the board and superintendent’s advisory council have helped shape and change such important policies as discipline, transfer, testing and grievances. Our union has successfully handled hundreds of individual grievances and supported teachers and their rights with picket lines and due process. With our support, teachers have documented the incompetence of administrators, which has resulted in their retirement, transfer or demotion.

Active AFT members usually enjoy a cordial relationship with the administration. There is more likelihood of duty-free lunch and voluntary extracurricular activities. There are elections of faculty councils, and the principals no longer believe they hold the title to the school building and the birth certificate of the teachers. The atmosphere has changed. In union schools, teachers and administrators function as equals to serve the same purpose — to help children make the most of themselves for a better life for us all.

Joining the union and standing up for my rights has made it clearer to me that there are other groups that are organized around equally vital issues of survival. It has given me the courage to join Carolina Action, a neighborhood group, to protest Duke Power rate hikes as inflationary to school and personal budgets; to march on the Democratic convention for more low- and moderate-income representation; to petition the city council for an evacuation plan for Charlotte because of the nearby nuclear plant.

The union has taught me how the system works and how to work the system for changes. It has taught me the true meaning of democracy — now I never miss a precinct or a union meeting. I’ve learned that when something bugs you, go to the appropriate meeting and make a motion. If it carries, something can get done. If the motion fails, give the people information, raise the level of awareness and, eventually, if the idea has merit, it will pass.

Many union members have been sent to seminars and conferences at various universities, the Carolina Labor Schools and the AFL-CIO’s George Meany Center for Labor Studies, and our eyes have been opened to dreams we never knew we had. We have seen collective bargaining contracts that unionized teachers have negotiated; we have studied the economics of North Carolina and the South. We have learned about past labor practices, grievances, arbitration, the Occupational Safety and Health Act and strikes. (Yes, I said the dirty word!) We have learned not to fear these things. They are our bargaining tools, our equalizers. We have learned the difference between myth and reality.

Editors’ note: Southern Exposure recently participated in workshops conducted by the North Carolina Association of Educators (NCAE), and found that dramatic changes inside the organization have turned it into a far more effective instrument for protecting teachers than it was a decade ago. In the last three years, progressive teachers have taken over leadership of the 44,000-member organization; the supervisors’ and superintendents’ division of NCAE was dissolved; and most administrators have left. Since state law prohibits collective bargaining for public employees, the NCAE has made itself felt through impressive lobbying — winning a wage increase from reluctant legislators in 1981— and through legal challenges to infringements on individual member’s rights. The latter range from suing a county school board for racial discrimination in its hiring of coaches and other extra-curricular faculty, to defending teachers’ right of free speech, to successfully opposing attempts to censor curriculum materials. NCAE is also in the forefront of the ERA fight in the state, providing office space to headquarter North Carolinians United for ERA and conducting workshops throughout the state on women’s rights. Other subjects in the organization’s aggressive leadership development and workshop program include political skills and campaigning, multi-racial leadership building, and understanding and combatting the Moral Majority and new right.

Tags

Brenda Best

Brenda Best has taught graphic arts and industrial communications to high school students in Charlotte, North Carolina, for 12 years. She is the mother of two teenage sons. (1981)