Speak Up, Speak Out, Say No

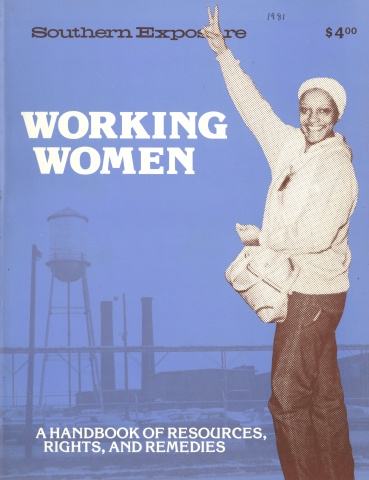

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 4, "Working Women: A Handbook of Resources, Rights, and Remedies." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

Most women workers are victims of sexual harassment. There are ways to fight back.

“My first mistake was letting the sheriff know just how much I wanted, the job. It gave him the upper hand, and he kept reminding me of the favor he had done by hiring me. One of the first things he said to me after I became a deputy — the first female one — was, ‘A new rule is going to be that females have to go to bed with me.' To that I replied, ‘Well, if that is one of the job functions, I’d have to find something else to do. ’

“He sorta laughed it off then, but after that he kept trying to get me alone in his office. There, he would grab me, try to kiss me and talk real dirty — I think he got off on that. I tried crying, but that seemed to delight him. I tried being angry, but that didn’t work. I threatened to tell my husband and county officials, but he knew how much I loved and wanted the job.

“When I did mention it to other deputies, they couldn’t understand and said I shouldn’t say things like that about the sheriff. But how could they empathize with me — he had never tried to grab at them or kiss them and they had never been threatened with losing their jobs if they didn’t play along. The county supervisors said that it was just a personality thing. ‘Oh, he’s just generally being a man, ’ they ’d say.

“I remember when it finally dawned on me how bad it was. He had ordered me to come into his office, and once I was in there he started grabbing at me. I found my hand going toward my gun. That frightened me, and I realized then and there that something was going to have to be done. ’’

— Nancy, a former deputy in Virginia

“I was the only lady security guard, and one of my co-workers was showing me around the buildings. We was checking for fires and to make sure the doors was locked. He cracked on me that very first night and kept aggravating me the rest of the time.

“He’d get me over in the corner and say, ‘There’s not a camera over here; they can’t see us here. ’ And he’d try to put his hands all over me. Later on, he was trying to get a safety supervisor’s position and kept telling me, ‘If I get it, I can do things for you. I’ll help you get an apartment as long as I’m the only one you ’ll see.’ I didn’t want to see him; he was about 45 years old, and I didn’t like him at all.

“I went to a captain to complain about it. He said he couldn’t do anything about it but that he would talk to personnel. Well, it never came to that. In a couple of months or so, they thought up some excuse to fire me — said I had helped somebody steal something from the company. I didn’t do it. I didn’t do anything.

“I guess I complained too much. . . . That was the problem. And I guess I complained to the wrong people. ’’

– Kathy, a former security guard for a Tennessee newspaper company

“My supervisor started showing an interest in me. He’d follow me home from work and insist on my fixing him drinks or something. He never really touched me, but he would say things like, ‘All you need is a good lay.’ Or one time he came into my office and asked me which finger I used to masturbate. I just walked out; I thought he was disgusting.

“This man was a Baptist preacher — he wasn’t supposed to be doing stuff like that. Luckily, they transferred him to another section.

“After a while, I went in to talk to another supervisor about it. He asked me, ‘Why didn’t you just quit?’ I thought what the hell kind of response is that, but then I realized there was really no other recourse but that.”

— Sharon, a counselor for a drug abuse agency in North Carolina

These women are victims of sexual harassment, and their words describe more vividly than any statistics can an old problem that faces working women.

Although studies documenting sexual harassment are relatively recent, slave women knew the problem well; few of them escaped the sexual advances of their keepers. White women in colonial America most often confined their work to the home, but sexual violence was still a part of the domestic picture.

Industrialization brought widespread sexual harassment. Examples can be found in the experience of women in New England textile mills, many of whom had left their homes to go to cities for work. Supervisors in the mills forced their attentions upon the vulnerable young women, who were then disgraced and sent home.

Nor was it confined to factories. Louisa May Alcott wrote a newspaper article early in her career about working as a housekeeper for a Reverend Josephus. The Reverend, as she described it in 1874, first lavished “tender blandishments” and later, when spurned, gave her only the ugliest and dirtiest of work.

Alcott’s candor about her experience is unusual, even today. Women’s continued reluctance to discuss sexual harassment is indicative of the misunderstandings, myths and complex feelings involved rather than a sign that it doesn’t happen often.

Even a definition of sexual harassment is hard to come by — the forms of harassment are as varied as women’s responses to them. But a basic definition is: any repeated and unwanted sexual comments, looks, suggestions or physical contact that is objectionable or offensive and causes someone discomfort on the job.

For some, it’s a lewd remark on the way to the water fountain or coffee machine. It’s being forced to listen to dirty jokes or obscene comments about other women in the office.

For others, it’s a pinch or a caress. It’s a suggestion that a trip to bed will start the climb up the career ladder or threats that if sexual favors cease so will a job. And for still others, it’s downright rape.

Women respond with a mixture of guilt, anger, fear . . . and silence. What happens all too often is that sexual harassment is meant to keep women in their place in the working world. The message women get is clear: you are more important as a sex object than you are as a worker.

The reluctance to come forward is one of the difficulties in coming to grips with the problem of harassment. Only in recent years have even sketchy surveys of sexual harassment been conducted. The numbers have been startling.

One of the first questionnaires on sexual harassment was distributed to women attending a forum at Cornell University in 1975 and to other women workers nearby. Of the 155 women surveyed, 70 percent had experienced sexual harassment at least once. More than 90 percent of them said that it was a serious problem. These included women of all ages, marital status, job categories and pay ranges. The victims included teachers, factory workers, professionals, waitresses and clerical workers. A 1980 study by the Kentucky Commission on Women found that 95 percent of the women state employees who completed the survey reported that sexual harassment was a problem. About 56 percent of them had actually experienced harassment, and, of those who had been harassed, 79 percent had experienced it several times or still were being harassed on a regular basis.

Women respond to sexual harassment in a variety of ways. But, all too often, the guilt and uncertainty that are wrongly associated with harassment generate some unhealthy reactions.

“While all this was going on, I began to question my sanity,” Nancy says now, some two years after she quit her job. “I started wondering what it was about me that let this go on and on and that there was nothing I could do to stop it. I felt somehow guilty and was reluctant to tell my husband everything, although I knew I had done nothing.”

Nancy’s feelings of guilt are typical of reactions to sexual harassment. “It’s as if someone were telling these women, ‘Hey, if you weren’t dressing a certain way or sending out signals, none of this would have happened,’” said the head of a Winston-Salem, North Carolina, women’s group. “But that’s just not true, although this guilt and the fear of being stereotyped as ‘easy’ kept women from speaking up.”

Few women know how to handle sexual harassment. Many, especially Southern women, have been conditioned to accept compliments grasciously and often the line between a friendly compliment and a sexual innuendo becomes hazy. Too, their conditioning has made them less assertive and unsure about how to express anger.

In addition, women have been encouraged to use men’s responses to their attractiveness as proof of their own self-worth. If a woman is “OK” then she is attractive to men. So any attention or harassment seems, on the surface, to be a positive reinforcement. Beyond this surface approval, however, lies a total lack of respect for the woman as an individual — a point which is hard to comprehend.

Many women say nothing about harassment, either comply or do nothing, and because of increased stress, nervous tension and other psychological problems, end up quitting their jobs — a move that keeps them confined to subordinate economic positions in the work force and tends to perpetuate the sexual harassment problem. Kathy and Sharon both tried to ignore sexual remarks and come-ons to no avail. The actions continued. Studies show that in about 75 percent of the cases where women ignored sexual harassment, the behavior continued or got worse.

But speaking up is not without its hazards.

After she complained about the sheriff’s actions, Nancy was relegated to duty on the courthouse monitors — a low-status job within the department. In addition, she and another female deputy, who also had been harassed, were sent out together to pick up mental patients. Always before, she said, that potentially dangerous assignment had called for a male deputy too.

Another female in the sheriff’s department later filed suit against the sheriff, prompting grand jury and state police investigations. Nancy and other females subpoenaed to testify were threatened, and after publicity mushroomed and Nancy told her story on television, threats were extended to her mother.

Charges were brought against the sheriff, but later dropped because of a technicality. The threats and disappointment were just too much for her, Nancy said. “I was scared to death. I moved to southwest Virginia, as far away in the state as I could get.”

Kathy is convinced that she was fired for what she calls a trumped-up reason because of her complaints to a supervisor. “I never got a chance to even tell my side of the story,” she said.

Many women feel that quitting their jobs is the only way to stop harassment, but other options are available.

First, a woman should recognize sexual harassment and understand that it is not her fault. Whether harassment appears as subtle comments and accidental touchings or flat-out propositions and attacks, a woman has a right to complain and take action. This understanding and determination is the key to reacting positively to sexual harassment.

Here are some positive steps to take:

• An immediate and emphatic “no” will often put a stop to sexual harassment. “If a woman can deal with it herself by telling a co-worker or a boss firmly that she doesn’t like what he’s doing, then fine, that’s the first step,” said Jone Eagle, who once worked for Rape Line counseling service in Winston-Salem. “Just tell him, ‘I’m here to do my job, and I don’t go along with that sort of thing and I’m not interested.’” If necessary, one woman said, pinch back. Many men will stop when faced by a determined woman who forcefully communicates that this behavior is intolerable.

• If harassment persists, evidence is important. Keep memos that detail any remarks and advances. For example, “On such-and-such day and time, so-and-so came into my office or cornered me in the elevator and said this.” A file of such memos or some type of record should be kept and shown to another person at work, preferably a superior. Lawyers say such files and memos are essential to a successful court case.

• Band together with co-workers. More than likely, the harasser has approached other women in the office, and they will have similar experiences to relate. If, as is often the case, a woman has only started working for a supervisor who is harassing her, she should try to identify the person who preceded her on the job (if a woman) or other women who recently transferred or left the company. These people possibly were subjected to similar treatment.

Collectively, women with similar facts and complaints will have more power and stand a better chance of getting action on their grievances.

• File a formal complaint with a supervisor, the personnel office or a union. Copies should be kept of any correspondence with management. Federal guidelines on sexual harassment were strengthened by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission [EEOC] in 1980, and employers were told to undertake affirmative programs to stop harassment. Since then, the federal government and some large corporations such as American Telephone & Telegraph and IBM have made it clear to employees that sexual harassment will not be tolerated; personnel directors have been put on notice that they must take action on harassment complaints. Many companies now are more sensitive to sexual harassment than they were in the past, and some unions include sexual harassment in their grievance procedures. Unfortunately, though, companies and unions are often male-run and are unsympathetic on this issue. But women working together can change company policy and union procedure.

• Seek the help of outside women’s groups. Many areas have local women’s advocacy groups, counseling services, human rights boards and commissions.

• Consider taking legal steps against the harasser. If harassment includes actual or attempted rape or assault, civil or criminal charges can be brought against the offender. In addition, a federal lawsuit can be filed. Sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination, which is outlawed — just like discrimination based on race, religion or national origin - by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Many women are afraid to take a sexual harassment problem all the way to the courts. They fear the long, complicated process and the public exposure that legal proceedings bring. Here is where women’s support groups can help. And women say that the legal process, although slow and at times unsuccessful, often generates a positive feeling of accomplishment.

“Once the legal action got going, even though I had not brought the suit myself, I felt somehow better,” said Nancy, who went to the American Civil Liberties Union for help and support. “And even though nothing was ever really done in the courts, I felt we had done our part in trying to get this whole thing stopped.” Publicity generated by the female deputies’ complaint resulted in an overwhelming vote to defeat the sheriff in the 1980 elections.

When cases were first filed in the mid-1970s, courts were reluctant, on the whole, to term sexual harassment “sex discrimination,” using arguments such as: (1) the overtures are purely private matters over which the courts have no jurisdiction; and (2) the actions are not discriminatory, meaning that one sex was not unduly singled out.

At least three recent court decisions, though, plus the strong guidelines issued by EEOC saying that sexual harassment is actionable under Title VII, have established the issue’s firm legal footing.

The three cases — known as the Barnes, Tomkins and Bundy cases — have clarified sexual harassment and helped to pinpoint circumstances under which an employer is responsible for the actions. Paulette Barnes was an employee of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Her job was abolished, she charged, because she refused to engage in sexual relations with her supervisor. She filed a sexual harassment suit, alleging dis crimination under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. She was eventually awarded $18,000 in back pay and attorneys’ fees in an out-of-court settlement. The Barnes case established that an employer — in this instance the EPA — is responsible for the actions of its supervisors. The appeals court stressed this, even though the employer might have had no actual knowledge of the sexual harassment.

The Tomkins case arose from similar circumstances. Adrienne Tomkins worked for the New ark, New Jersey, office of the Public Service Electric & Gas Company. She alleges that after she became eligible for promotion, her supervisor asked her to lunch, ostensibly to discuss her promotion. There, he made sexual advances and suggested that she would have to have sex with him in order to ensure her promotion and a good working reltionship. She refused and was detained by him against her will and threatened. She later complained to the company, after which she was demoted and began receiving poor job evaluations. Ultimately, she was discharged.

The court ruled that the actions constituted sexual harassment and were illegal under Title VII. The Tomkins case also set up a four-part test for determining whether Title VII is violated by this type of incident.

• A supervisor makes sexual advances toward an employee;

• Continued employment or job status is made contingent upon the employee’s submission to these advances;

• Higher management knows or should know of the incident(s);

• The employer does not take prompt and appropriate remedies.

The courts went one step further in a 1979 ruling, saying that a company is responsible for the acts of a supervisor, even though officials of the company may not have known of the conduct.

Sandra G. Bundy was a vocational rehabilitation specialist for the District of Columbia Department of Corrections. She complained that men at work were constantly harassing her, but her complaints went unheeded or generated remarks such as: “Well, any man in his right mind would want to rape you.” She also said that she had been denied a promotion that she was due.

In 1981, the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washing ton, D.C., overturned a lower court’s ruling on the Bundy case in a strong decision. Comparing the harassment to racial epithets, the court said that racial slurs (and likewise sexual innuendos) are not in and of themselves discriminatory, but they affect the work environment sufficiently to violate Title VII. Also, the court said that Bundy did not have to prove some direct discrimination or retaliatory action.

Lawyers cite this case as a victory for sexual harassment litigation: “Sexual harassment was really an open question until this,” said Ron Schecter, a Washington, D.C., lawyer whose firm specializes in Title VII cases. “This is the first case that came out and said that sexual harassment should be stopped.”

One other case deserves mention — largely because it indicates a new area into which sexual harassment cases might move. A federal lawsuit was brought recently by Judith Marantette, a waitress at Detroit’s Metropolitan Airport. She and other airport waitresses have filed a class-action suit against their employers, Michigan Hosts, Inc., charging that the short, ruffly, low-cut uniforms they are required to wear subject them to sexual harassment by customers.

Uniform cases are not new to the courts, but the sexual harassment aspect of the Marantette case (and a few other developing cases like it) is a recent trend. Essentially, the women in the cases are arguing that because they are women they are expected to wear sexually revealing uniforms and to endure the resulting sexual harassment as part of the job.

In Detroit, the women are awaiting a court ruling on a challenge by their employer on whether they may sue under Title VII. But in a similar case in New York, a woman recently won a favor able ruling.

Women’s rights advocates are viewing such cases with great expectation that they will affect other waitresses, receptionists and all workers who are required to dress a certain way to satisfy male employers.

Sexual harassment — like other forms of discrimination — may never be wiped out. Men and women who have been conditioned to assume certain roles will continue to have difficulty coping with changing roles in the work place. Sexual harassment will continue to be a tool to manipulate women and keep them in their place. But with increased education and awareness of the problem, fewer women will tolerate sexual indignity in the work place. Recent successful court cases and recognition by the federal government and private business of the sexual harassment problem are positive indicators that sexual harassment is, at long last, emerging from its murky past.

Kathy and Sharon now have jobs elsewhere. Kathy reports happily that sexual harassment is no longer a problem for her.

On a subsequent job, Nancy’s boss started making what he considered innocent sexual re marks. “I bristled, and all the feelings came rushing back,” she recalls. “There was no way I could even giggle with a boss anymore. So I just came out and told him that as a woman I didn’t think I should have to put up with it. ... I made no bones about it. I think it sorta surprised him.”

She no longer works full-time. “I don’t know that I’ll ever get over it. I don’t think I will ever enjoy working again. But I guess I’m glad I went through it all.

“It’s something every woman should learn from, and men should take notice that women are going to start trying to do something about it.”

Tags

Sylvia Ingle Lane

Sylvia Ingle Lane is city editor of the Winston-Salem Journal. She has reported for the Journal and the Durham Morning Herald. (1981)