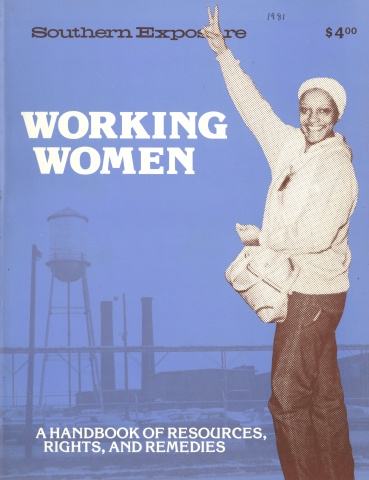

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 4, "Working Women: A Handbook of Resources, Rights, and Remedies." Find more from that issue here.

In 1978, workers in the gigantic Newport News shipbuilding yard owned by Tenneco Corporation voted to be represented by the United Steelworkers of America. After the company stalled negotiations, the workers struck in 1979 for 83 days. In a major breakthrough for organized labor in the South, Local 8888 won a contract covering the yard’s 16,000 workers.

Because of laws won by the Civil Rights Movement, the shipyard began hiring women in traditionally male jobs in 1973. By the late ’70s, one-third of the production and maintenance workers were women, and they have played an important role in the union. In the process, they have watched their lives and personalities change. Of the women quoted here, six are white — Paula Axsom, Nancy Crosby, Jan Hooks, Judy Mullins, Sandra Tanner, Ann Warren. Three are black — Cynthia (Cindy) Boyd, Peggy Carpenter, Gloria Council. “We got to know each other on the picket line, ’’ said Peggy Carpenter. “Oh, we may get mad now and then, but we say what we have to say, and we work together. We know who the enemy is. We stuck together, and it paid off.”

Ann Warren, mother of two sons, now grown, Steelworker delegate to Newport News Central Labor Council: I was one of the first women ever to work on a ship. I hired in on October 4, 1973. I was separated from my husband, my sons were still little boys, I knew I could not support them on a minimum-wage job. Then I saw a newspaper ad that the shipyard was going to hire 1,000 women, so the next morning I was there. The government had told them they had to hire a certain number of women, to comply with EEOC [Equal Employment Opportunity Commission].

I hired in as a tack welder; now I’m classified as a mechanic in the shipfitters. We do very heavy work. I’ve worked with steel foundations that are bigger than a couch. I’ll never forget that first day in the shipyard. They put me underneath a ship, held up by the big pillars. A young man was going to teach me; 10 minutes later he leaves and for a half hour I sit there looking at that huge ship over my head, thinking, “God, don’t let it fall.”

At first, I got a lot of static from the men. “This is no place for a woman, you ought to be outside taking care of your kids.” I got angry one day, and I told one of the guys that I had to feed my damn kids just like he did, that’s why I was there, and I never had too much trouble after that.

Sandra Tanner, a painter and member of Local 8888’s safety and health committee: I went to work in 1976, and there still weren’t many women in the paint department where they put me. I’d never done anything like this before. I grew up in North Carolina; my father worked in a textile mill, my mother never worked outside the home. I did clerical work for W.T. Grant, worked up to management. They went out of business, and I came to the shipyard. I’ve always been the prissy type, and my brother said, “You’ll never make it through the winter.” It was cold, no heat anywhere on the ship; you had to eat outside, or in the bottom of the ship because you had only 20 minutes, and you never knew whether your lunch would be there, because a big rat might come and take it right out of your tool box. But I made it through the winter. Then my brother said, “You’ll never make it through the summer, it’s worse, it’s so hot.” But I made it through the summer, and I’m still there.

Jan Hooks, twin sister of Ann Warren, mother of two daughters, editor of Local 8888 s newspaper, The Voyager: I’m a crane operator. The cranes fascinated me from the day I went in the shipyard. That was after Ann was already working there. My second husband was a serviceman and we lived all over, but when I moved back here my second husband and I had separated. I had two daughters, and no job. I’m trained as a secretary, but I enjoy being outside. Ann said come to the shipyard. My department is grunt-and-groan work; it’s classified as an unskilled department — primarily black uneducated men. And I’ll tell you those uneducated black men accepted me a whole lot quicker than anybody and went out of their way to help me. The white men in the age bracket from 30 to 45 were the ones I had the biggest problem with. They seemed to feel the most threatened.

My first day in the yard, I was sent to the bottom of a ship. They put me in a little hole, with no lights, and gave me a two-inch paint brush and a metal shovel and told me to clean this hole out. I was scared to death; it was hot as all get-out. But one woman working with me pulled me out, and she jumped all over the supervisor, told him no woman, no worker, was going in a tank by themselves without a light, or ventilation.

Warren: When I first went there, they had only one bathroom for women in a six-block area. We raised cain, six women fighting the whole shipyard So they brought us two portable johns, and the men used them at night, and they stayed filthy. We got a padlock and locked them. One day, it was real hot, and one of the girls was angry because the stench in the john made her gag. A construction supervisor — one of the biggest men in the shipyard — was down on the shipways; she grabbed him by the hand, put him inside the toilet and locked the door. She made him stay in there about 10 minutes, and it was hot and it stunk. When he came out, he was heaving, he was so sick. He said, “Is this the only thing you all’ve got?” And two days later we had the prettiest and brightest brand new toilet you’ve ever seen.

In 1976, five men formed a committee and asked the steelworkers to help them organize. Women soon joined.

Peggy Carpenter, mother of a nine-year-old daughter, a welding inspector and financial secretary of Local 8888: Before we had the union, the supervisors felt they could talk to you any kind of way. And they would promote their girl friends, or women they liked; there was no seniority.

Warren: Jan’s and my father worked in the shipyard before he retired, and he was so proud of us both. He took us both out and bought us our work clothes when we first went in. He’s always been ahead of his time — brought us up to show no partiality to anybody, black, white, man, woman. And he knew about unions, because I remember walking a picket line with him when we were four years old. That was in the North Carolina mountains in the ’40s, at a big laundry. Jan and I went and asked our father what he thought about the union. He said yes, a union was probably the best thing that could happen at the shipyard, and if we wanted it to go after it. So we both did.

Judy Mullins, a machinist and a leader in Local 8888’s work for passage of the Equal Rights Amendment: It was different with me. Union is something I did not grow up with at all. My dad worked in the shipyard, but he said don’t join the PSA [Peninsula Shipbuilders Association, the company-controlled union that then represented the workers]. He still considers the Steelworkers crime and corruption. But in the yard, I listened to the men complain — I mean from day one, I heard them — about working conditions, low pay, lack of benefits, management pushing people around, unsafe conditions. And I knew a union was needed, here was a chance to change things 100 percent.

Gloria Council, a welder and recording secretary of Local 8888: My sister was in the union before I was. The company made up things to fire her. But the union fought and got her job back. So I saw what a union could do.

Local 8888 includes about as many office workers as production workers. Women who were pioneering in the heavy work on the shipways soon found allies among the women who worked in the offices, many of them on the highly technical computer jobs.

Paula Axsom, mother of two grown children, now Tidewater coordinator for ratification of ERA: I’m a materials supply clerk, I monitor books for spare parts, it’s a bookkeeping job. Those of us in the office were lowest on the totem pole in salary. Before we got our contract, they were hiring clerical employees at minimum wage. I had been at the shipyard 15 years, but production workers who had been there just a few years made more than I did, and I was topped out as to where I could go. All that has changed with the union.

Cindy Boyd, mother of two young children, now co-chair of Local 8888’s compensation committee: I work in the office, and actually I was doing pretty well before the strike. I’d been there seven years, my father was in service, and I worked summers during high school for the government, hoping I could someday be a clerk-typist. When I got the job at the shipyard, they trained us on computers, and I thought it was marvelous. The reason I went out on strike is that my husband works in the yard, and I knew what he was going through, being a black male in that shipyard. Not just him, but the women, too, with bad working conditions, unsafe, no benefits. So we both came out on strike, and I was scared, we have two kids, and we didn’t know if we would have a job again, but we decided to make that stand.

The computer operators put the company through a trick when we went out. We knew our jobs, we trained other workers, but we never wrote down procedures. We took that information out with us in our brains, and the supervisors didn’t know how to get the work out, they really messed up the computer system.

When we got back, it was terrible. Harassment like I’d never heard of before. I had to go to a doctor and get medication. And they took away all the interesting duties we had, gave us menial tasks, and I finally asked for a transfer, and now I’m a materials supply clerk. That’s when I learned I had to fight — because they weren’t giving me anything. I used to cry when supervisors would harass me, but no more, I fight now just as hard as they fight me.

Nancy Crosby, who, before the union, worked on a highly skilled job in the yard’s computer center: We all learned to be fighters. I worked in a highly secured area, very interesting work. Then my husband (Wayne) got active in the union and became president, and they took many of my duties away from me and finally transferred me, supposedly temporarily, to another job. They didn’t trust me. I was in a salaried position and was not eligible for the union, but when the strike came, I went out too — stayed out with the others, walked the picket line. After the strike, I asked if I’d be put back in the computer center, but they said the job was no longer available. So now I have a clerical type job in the design unit, where I belong to a different Steelworkers local, 8417. We’ve all given up some things for the union — but we’ve gained more. I learned about unions in Georgia, where I grew up. I was one of eight children, my dad died when I was 11, and we were very poor. I got a job as a store clerk to put myself through high school.

But after I was married, Wayne and I worked together in a small Georgia can plant, and we helped organize a Steelworkers local there. Whether you are in an office job or on the shipways — I know that shipyard management has a lot more respect for those people they know will stand up to them.

Warren: So we were all together. I’m an old shipyard worker, I stay dirty, and Cindy and Nancy and Paula, they’re nice, working up there in the office. But there we were, working side by side, in the union hall, on the picket line, during the strike.

Local 8888’s strike in 1979 was rough. Many strikers were arrested. State and local police attacked the strikers brutally on several occasions.

Axsom: When the strike began, the union organizer said he didn’t want women on the picket line, he was afraid we’d get hurt. But the women went anyway.

Warren: One of the first ones who got arrested was a woman. Police arrested her husband, and she made a flying leap and tackled the lieutenant, bodily to the ground. It took four of them to put her in the cop car. And we had a policeman with a camera, he’d harass the devil out of people, so we ganged up and covered one gate with 50 women, and every time that cop brought the camera up, we posed for him; we harassed him until they finally took him off the gates. Even the wives came out, mothers pushed babies in carriages on the line.

Tanner: Since the strike, we’ve learned so much, about our rights, about safety. That yard is a dangerous place. When I first went there, working in the paint department, they put me to busting rust. That’s grinding rust off the ship hulls so they can be painted. My supervisor never even showed me how to hook up my grinder. It has no guard, so not knowing how to use one, you could cut your hand off. I busted rust for three days before I even knew what a respirator was. They had respirators, but they didn’t educate the people. When we came off the ships, you couldn’t tell who was white or black, we were covered with rust.

But with the union, we started having safety meetings once a week, and they educated us so much. I got to arguing with my supervisor all the time about how we needed ventilation and more safety equipment. I stayed in a lot of trouble, but I figured my lungs were worth it. I got so interested in safety that I’ve gone back to school part-time. I only finished high school before, but now I’m at the community college, studying occupational safety and health.

Warren: None of us knew the rights we had under federal law. The state is not that much, but federal laws like EEOC, the Civil Rights Act, labor laws, our rights under OSHA, we learned all that.

Council: You always had the right to refuse to do dangerous work, but before the union there was no one to guarantee that right. Now there is. The main thing is that the company knows now that we are not afraid of them.

Carpenter: I come from a struggling family of women. My mother and father separated, my mother worked in a chicken plant, plucking chickens, and went to school at night. She was a strong woman. I think I’m naturally like her, and the union brought out the real me. And it gave me a chance to use my ability. I didn’t go to college, but math was my favorite subject, so when I first went to the yard, I tried to get into clerical work. I’m glad now I didn’t, because I’m using my math as financial secretary for the union.

Warren: That shipyard has always made the women, and the men too, feel like they were stupid, ignorant. But they found out through the Steelworkers and our learning process that we are not ignorant people. For example, Jan had never worked with social services in her life, but she handled food stamps for the whole strike. She got to know everybody within a 200-mile radius who dealt with social services. Cindy is now one of our leaders, co-chair of workers’ compensation. One of them, head of the compensation committee, went to Washington recently to testify on that. The shipyard has found out that we are not as stupid as they thought we were.

Women are fighting back against sexual harassment on the job now. One woman took a supervisor to court, and he was fired. She had asked for a raise and he said, all right, if you’ll sleep with me, only he used cruder words. Now this was a white supervisor and a black woman — and she went back and asked him again, and he did the same thing. And she taped him.

Crosby: So now they bar all tape recorders from the yard area.

Tanner: But the company is also turning it around and trying to use the sexual harassment thing to turn worker against worker. They’re now telling our co-workers they’ll get fired for sexual harassment.

Hooks: The discrimination is still so rampant. In my department, you see so many white guys that are supervisors, or specialists, and there’s not a single woman above third-class mechanic. The work force in my department is 80 percent black, and I bet not two percent are above mechanic.

Warren: As far as this company is concerned, the people in that shipyard are either white men, or they are Southern white gentlewomen that don’t have any business working, or they are niggers. And I mean they actually call them that, sometimes to their face. Some women, white and black, have been made supervisors, but they are tokens. The government told the company to comply with EEOC, so they find women who scabbed. A decent supervisor who treats people right, man or woman, gets shafted. They want supervisors who will stay on people’s backs all the time.

The women — along with union men — have gone into politics. In 1981, Local 8888 representatives, in coalition with several other unions, took over local Democratic conventions in Hampton and Newport News and elected most of the delegates to the state convention.

Warren: We don’t have anybody in office around here who will stand up for working people. Whether it be on city council, in the House of Representatives, senators. And we figure we have to start here and put the people in that we need. The only way you can do that is register to vote, and you’d be surprised how many people on the Steelworker rolls were not registered to vote.

Axsom: So we ran a telephone bank. It’s estimated that at least 2,500 people registered through those phone banks. Soon we’ll be gearing them up again.

Warren: Tenneco put on a campaign in the community for four years saying the Steelworkers were trouble with a capital T. So the whole area got against us, first because we were women in the shipyard, then because we were Steelworkers.

Axsom: But I think we are turning that around now. Not totally, but people are coming around, people who were scared of us, they are knocking on the door, they are calling. Carpenter: This is something new for the South. And I think more unions, more working people, are going to get together, statewide, nationwide. We know what we want; we want a fair shake. We don’t need to be rich or have a big Cadillac. We just want to be able to live and raise our children and not have to struggle every minute. I saw my mother struggle so, working in the poultry plant, and never have anything for it. Oh, we never went to bed hungry, she saw to that, but it was such a struggle for her.

Warren: We’ve got to fight together, or we’ll have nothing. One person can’t do anything, but when you’ve got people behind you, you can accomplish things.

Mullins: And for the betterment of everyone. Not just for us, but for everybody, try to make things better in our work place and in our community. Because we are not going to make any changes in what’s going on in this country until we can make changes in our own community. And that’s what we’re trying to do, make things better for everybody.

Tags

Anne Braden

Anne Braden is a long-time activist and frequent contributor to Southern Exposure in Louisville, Kentucky. She was active in the anti-Klan movement before and after Greensboro as a member of the Southern Organizing Committee. Her 1958 book, The Wall Between — the runner-up for the National Book Award — was re-issued by the University of Tennessee Press this fall. (1999)