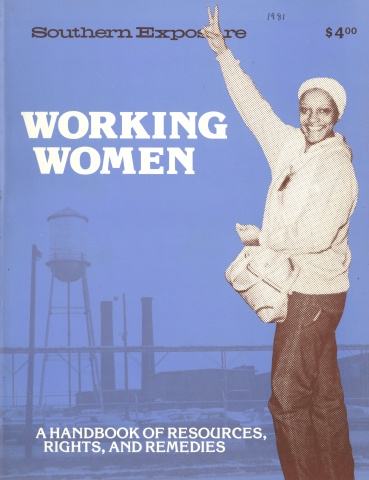

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 4, "Working Women: A Handbook of Resources, Rights, and Remedies." Find more from that issue here.

Labor union women from 13 states and 17 unions across the South came to Kentucky to participate in the 1980 Southern School for Labor Union Women.

“A few years ago, people said that Southern women wouldn’t turn out for this kind of school,” said Debra Barnett, a labor educator from the Tennessee Learning Center. “But they were wrong. There’s a growing movement. This is the beginning of a new era in the South.” Southern union women are becoming more involved and are learning to assume leadership roles in their unions.

The first modern-day women’s school in the South was organized by Marge Rachlin and Judy Ellis of the University and College Labor Education Association (UCLEA)Task Force on Women and was run on a shoestring budget at the Presbyterian Center in Montreat, North Carolina, in September, 1977. Rachlin talked of the initial skepticism they met with when they first raised the idea. “The idea was to provide an opportunity for Southern women to share their experiences and learn skills to work more effectively in their unions. Some said it couldn’t be done, that not enough women would be interested; but we went ahead with it anyway. Fifty-eight women attended the first women’s school. We ran a quality school; we broke the ice and proved that we could get the support of the state federations of labor and that women could get their locals to send them for training.” Since then the school has grown, with 85 women attending in 1980. Angie Celius, a hospital worker and member of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), Local 1991, in New Orleans, went home from the 1979 school and helped organize a local chapter of the Coalition of Labor Union Women. According to Celius, “The first year, I came to the school by myself, but then I came back and brought six new women with me. That’s how our movement’s growing. We’ve got to keep organizing. We’ve especially got to get the younger women involved.” Why a special school for union women? According to Debra Barnett, “Women are traditionally excluded from leadership roles in their unions where they would gain experience to contribute to the union cause. In practical terms, when labor schools are held, women traditionally are not sent.” As a result, they are afraid to get more involved in their unions, afraid they lack the education and qualifications. As Silvia Hobbs of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) noted, “I’ve been a union member for 11 years, but I only became active in the last year or so. I always wanted to get involved but was afraid to because I didn’t think I was qualified. I think it’s hard to get other women active because they feel like I did.” Now Hobbs is a shop steward and is finishing her high school education.

There are special difficulties faced by working women, particularly union women who live in Southern right-to-work states. Suzanne Feliciano of the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), Local 227, went straight to the point. “We live in the most male-dominated and anti-union region of the country. Domineering men make it hard to organize women, and anti-union management is much stronger in the South. It’s double jeopardy.”

Women in the South are concentrated in industries which have a predominantly female work force. Yet they work under male-dominated management and not uncommonly face sexual harassment. Under such conditions they often feel intimidated and reluctant to assert their rights, particularly when high unemployment rates make them “easily replaceable.” As workers concentrated in low-paying, traditionally women’s jobs, they must often work overtime to make ends meet. And as working mothers they have two jobs. Gladys Draugn, a member of Local 3177 of the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU) in Ruffin, North Carolina, finds it hard to attend union meetings because she works seven days a week to support her family. Silvia Hobbs is a mother of nine and works 12 hours a day, five days a week to support her family. As she says, “To take care of a family and work at the same time is a constant uphill struggle.” Like other women, only since her children have grown up has she been able to become active in her union.

Women are also concentrated in industries which are traditionally non-union. Nationally, seven million — 16 percent — of the 43 million women in the labor force are organized, as compared to 33 percent of the male labor force. But in Southern right-to-work states, the proportion of unionized workers is considerably less. Organizing the unorganized was a major concern of the women attending the school, many of whom had worked on organizing drives in their own locals. Rosa White of UFCW Local 223 in Norfolk, Virginia, was one of them. “In our area there’s no way anyone can learn anything about unions that’s positive. There’s too much anti-unionism. That’s why I came to this school. What I’m interested in is organizing.”

Another theme of the school was the problems faced by women in nontraditional jobs, including sexual harassment, discrimination and economic insecurity. Women are particularly hurt during this period of economic recession, when they are among the last hired, first fired. “The fact that I have skills doesn’t help me that much,” says Nesta Duncan, an industrial electrician at the Union Carbide atomic plant in Paducah, Kentucky. “I don’t have it made except at a plant large enough that it has to comply with government regulations and will hire me because of that. Otherwise, my being a woman will hurt me.” Almost a thousand workers were laid off at the Paducah Carbide plant in 1980, including most of the women, “because they were the last hired. The women who remain will almost all be janitorial or laundry workers.”

Women who attended the school went back with a new set of skills and knowledge and renewed energy to work actively in their unions. Participants eagerly went through a week of training in technical areas such as grievance handling, collective bargaining, costing a contract, health and safety regulations and parliamentary procedure, as well as broader areas such as public speaking, assertiveness training, organizing and political action. Evening classes were added to the schedule as participants requested supplemental instruction. Women discovered their own union legacy in a special class focusing on women in labor history which dispelled some common myths about working women and reviewed the important roles that they have played in the labor movement. For example, Della Freeman of North Carolina Local 294T of ACTWU came away from the class and said, “When I look back and see what women workers of the past have been through, it just makes me want to get in there and fight. I’m 55, and now that my family is grown, I have more time to devote to the union. If I can make it easier for my daughter and my granddaughter, then that’s what I want to do.”

Rosa White, a three-year veteran of the school, paid her own way back this year when her local’s treasury was depleted after a recent organizing drive. “I came back to the school this year to recharge my batteries. This school makes a difference because you know you’ve got all your union sisters supporting you.”

“It’s just too bad that every union woman couldn’t come to a school like this,” added Beth Hargrave of the United Auto Workers, Local 561, in Tennessee. “It gives you a lot of determination to go home and work in your union. And you really get a good idea of how women in other jobs and unions are treated.”

Tags

Laura Batt

Laura Batt is an organizer with the National Union of Hospital and Health Care Employees, 1199. This article is reprinted from Kentucky Labor News. (1981)