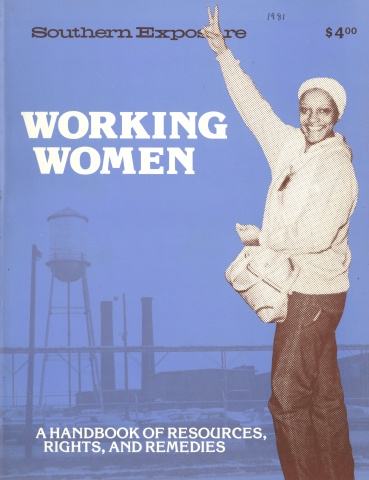

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 4, "Working Women: A Handbook of Resources, Rights, and Remedies." Find more from that issue here.

In Memphis, a thousand workers won a 10-week strike by building strong support in the community.

On March 12, 1980, the workers at Memphis Furniture, members of United Furniture Workers of America Local 282 in Memphis, Tennessee, voted to strike rather than accept decreased benefits, poor working conditions and a weakened contract.

The United Furniture Workers had won a representation election in 1977 and signed a two-year agreement with management in March of 1978. From the time Local 282 began negotiating renewal of that first contract with the company, it was clear that management wanted to break the union. Twice before, in 1949 and 1962, Memphis Furniture had been able to block union attempts to get contracts after workers had voted for union representation.

Local 282 of the United Furniture Workers, headed by Willie Rudd, a dynamic young trade unionist, used a variety of tactics in the strike. The local sought and got union and community support, organized significant participation in Memphis’s annual Martin Luther King, Jr., March, held numerous rallies, leafleted the communities and shopping centers, and organized informational pickets and a boycott of Memphis Furniture products at leading stores in Memphis, including Sears.

It wasn’t tactics alone that won the strike. A big factor was the spirit and determination of the more than 1,000 Memphis Furniture workers — 90 percent of whom are black, 85 percent of whom are women — who held strong during the approximately 10-week-long strike.

Emma Freeman is the mother of four, head of her family, a 12-year employee of Memphis Furniture and a union steward. Mary Higgins is the mother of two children, wife of a United Auto Worker, a four-year employee of Memphis Furniture and a steward.

Mary Higgins: Most of the workers are the only ones that can support their families. One woman supports her entire family. And if she is laid off, then she doesn’t know how she is going to make it next, you know. But yet she was willing to put it all on the line during this strike. I think that took great courage on her part to do something.

Emma Freeman: Before the strike I think most of the people were making minimum wage or a little above. You wouldn’t believe the seniority record out there. The people are staying because they want to work and they need to work. At most jobs, the longer you stay on the job the better you would have it, but it wasn’t that way at Memphis Furniture.

Higgins: You could get hired today and fired today. You had to bring in all kinds of reasons why you were late or absent. The boss would even talk to you any kind of way. It was just really poor.

One lady had been with the company, I’m sure, 30 years. She was sick and she had to go home for a couple of weeks and she came back to work and the supervisor was telling some employees up front, “If she’s that sick and can’t build enough drawers to keep up, she oughta go on and retire.” Before she got sick, he used to brag on her all the time: “Why don’t you work like Annie there? She’s a hard worker. She works steady. She can put out a thousand drawers a day. Here you are and you can only put out 600 a day.” And once she gets sick they’re ready to cut her loose. Just like you would a mule with the plow. All they wanted was just work.

Freeman: Some of the people were on food stamps and then they were getting AFDC. You know, for a person that worked — with the husband and wife working at Memphis Furniture — they shouldn’t have to rely on food stamps.

Higgins: I am sure that quite a few of them were afraid they were not going to be able to make it during the strike, but they were willing to take a chance. It isn’t any better in there, so it couldn’t get any worse out here. So I think that was the attitude that most of them had — that we’re going to give this a try. We’re just not going to live under those conditions any longer. We simply refuse!

It really seemed to me that the strike was pushed on us, mostly by the company. And we did everything possible to avoid a strike. We went to the table in good faith. No, they laid down their last, best and final offer. Things were really getting tight. We didn’t have anything else to give up. We’d given up as much as we possibly could.

Freeman: [There were other issues besides money.] There was the insurance, there were job classifications; there were other things as far as holidays, holiday pay; just about everything that makes up a contract, really.

Higgins: On the insurance, they said, “Blue Cross and Blue Shield.” We said, “Furniture Workers Insurance.” There was a great debate over that. The majority wanted the Furniture Workers, so that’s why we went in there with that. Because they felt that the Furniture Workers gave them better benefits and more assurance than just dealing with the company, so they felt better with Furniture Workers than they did with Blue Cross and Blue Shield.

During the strike, we had a picket line. The stewards pitched in and helped organize things. Like I had some three-to-12 shifts at night — you did a shift and you were totally responsible for it. You were captain of that shift. It was your responsibility to see that everyone showed up, was on time, jot down their names and what time they got there and what time they would leave. And you wouldn’t know that if you weren’t there. It was your job to be there.

Freeman: We even had neighbors to come out there with us. And we had just a great turnout in the morning time and we sang songs and we let them know that we were determined to win. And not only did we have the support of practically everybody that worked in Memphis Furniture, we had the support of the community, of our churches and everybody else. Everybody was pitching in. The attitude with the people — it was just like you would see in a revival at a church. It was just remarkable!

We went from door to door in our different communities. The ones that were active in church — we went to our church and talked, got up and asked the pastor could we have a word about our strike. We talked about our strike in the church and anywhere else. We let them know how Memphis Furniture was treating us. We let them know approximately the salary that people made out there, the conditions in which we worked. And they weren’t aware of this. And so when they became aware of it, you know, naturally being human, they felt our need. Before the strike, our president told us to talk to our bill collectors and let em know that we might go out on strike. And if we do that we wouldn’t be able to pay our bills. And I went to where I have my car financed and I talked to them and let them know that I might not be able to pay it. I called where my house is financed. I just called all of them, to let them know that we weren’t trying to avoid paying our bills, but that we might be a little late paying them. And our union helped us out. They footed some of the necessary bills. The union was just great.

I didn’t have any problem with my children. Before the strike, we anticipated the strike because of the way they were negotiating. They weren’t trying to do anything, be fair at all. So I told my children that we would possibly have to go out on strike and if we did there wouldn’t be any money coming in. The things they were used to getting would have to be cut out and we would really have to cut down on everything. The bills probably would get behind, but don’t worry about it, that everything would be okay, but they had to work with me. And they were understanding.

As a matter of fact they came out with me. They were in school at the time, but when we had a big turnout, when we had to get there in full force and we was asking our neighbors and our friends to come out, I had my family with me. And they were wearing United Furniture Workers T-shirts. They were carrying signs and carrying water to various people that needed it. And they were just helpful; if someone wanted to go to the bathroom, they would walk in their place until they got back.

Some of the people who were out on strike and were walking, they weren’t even members of the union before we went out on strike. But they knew the need and they knew what the union was for. There are a lot of young people who work at Memphis Furniture who had never worked at any other job before coming to work at Memphis Furniture, so they had never been involved in a union. They didn’t know what a union was or how it would help them. So when we voted the union in, a lot of them didn’t join because they felt they could get along without it. But after we went out on strike and they saw just the way the company felt about them, they felt differently. They knew then what a union was for. We had so many joining the union while we were out on the picket line and the majority are still in the union.

We weren’t sure we were going to win the strike, but we were determined. We had that extra fight in us to continue. Some of the people who weren’t going to church joined and went to church. We had prayer and, you know, prayer changes things. I am a firm believer in that. We prayed together. We took “self” out. And anytime you take self out and just try to do what you can to help others — not only thinking that you are helping yourself - you’re helping somebody else also.

Higgins: One woman had bought a house and she said, “I’m wondering how am I going to pay my house note.” She told another lady, “Here I am out here without a husband, and I have a son and I’m not complaining. Why should you? I’m not going back in that plant and work under those conditions without a contract and I don’t think anyone else should.” And I think that was strictly beautiful. She had her job on the line, her house on the line. She had it all on the line because she believed in what she was doing. She believed that she was going to win. We knew that if one person could be that dedicated — then we could.

During the strike everyone was just out there doing their best. And they felt — “If I can do my best, then everyone else can do their best. At least participate in some way. If you can’t march — sing. If you can’t sing - just stand there. Just be there. You should be able to participate in some way.” The ones who didn’t participate in the strike, I think they felt a little bad about themselves because they went around and moped because no one would talk to them.

Freeman: When we walked the picket line we got gas money. We got $20 if we walked the full week. We were able to make it. It was hard, but so was it before the union came in and we were working 40 hours and sometimes 50, but it was still hard. So we were used to hardness. So we just had to deal with it. We were able to get more food stamps and some of them would get little part-time jobs to support us.

If it took going to jail, we did that. Whatever it took to win the strike that was legal and that was right, we did it. There were some of us who went to jail, but at the same time they couldn’t get us on anything because we were in our rights. They were the ones that were doing the under-handed things.

Going to jail was funny because this was something that we never had to happen to us. It was four of us together. We had never been handcuffed before. When we were going inside the jail, we were singing, “We Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Us Around.” We still had the fight. We still had the spirit, because we knew what we were doing was right. When we got inside the jail, the matron didn’t even lock the cell door, because she asked us who were we and what were we there for. And we told her we were Memphis Furniture employees; we were out on strike. She asked us what we were out on strike for and we told her: conditions, wages, benefits and everything that we were out for. She said, “I don’t blame you. Keep on!” She put us all in a cell together where we would feel together — feel good. She talked to us. It was funny to be there and see the inside of the jail cell — something you had been reading about and seeing on TV, you were a living witness of it. But after staying there many hours and seeing the food — Oh my God, the food was terrible! I was actually sick from eating that food.

We had to go through this ordeal of being fingerprinted and asked questions and notified of our legal rights and everything and we realized then that it was more serious than what we anticipated — what we thought — but at the same time we knew we hadn’t done anything wrong. We just knew it was a matter of time. When our president came down there and we saw him, I started crying. I had had enough of that jail cell. We got out and he asked us were we scared; and we told him, yeah, we was afraid, but at the same time we had the strength to believe and we knew that “We Shall Overcome.”

Higgins: If I had it to do over again, I would. It was worth it. Right now if I walked down through that plant, I’d feel it was worth it. Where you would normally say, “There’s a hazard over there on that floor; it needs to be removed because somebody’s going to fall on it.” The supervisor might say, “Well, get it up then!” Now he’ll say, “Okay, Mary, I’ll go see about it, and I’ll see what I can have done about it.” The next minute or so he will have somebody to move it or straighten it out. Now he will ask, “What do you think about this?” I think that’s great — to get your opinion about something before you would do it.

We definitely went out for respect — more so, I think, than money. It was just outrageous the way they would talk to you — like you was nobody. If you don’t have respect in the shop, you don’t have anything. You got to have respect. First, you got to respect yourself. Then you got to make sure he respects you. And you got to know that contract. You got to make sure that he lives up to that contract.

The strike made me see more about what the union is really like, what it’s really about: dignity, self-respect. It just put it all there. And it just makes you want to say, “This is my job. I am proud of my job and I have a right to this job. I have a right to my opinion.” I know I want to feel like this and my union feel like this. And we are the union. And it makes you feel like you have support. And I think we did a good job. We had to.

Freeman: The strike didn’t actually change my life; at the time, you know, it changed my living standards from poor to worse, but it just brought my family even closer together. You know, children have a tendency to think that money grows on trees. They don’t even think about where the money is coming from. Mama’s going to provide when they need it.

Higgins: The first thing I would say to people going out on strike is, “Be together.” That’s number one. Be together. Don’t go out there thinking now this might be over tomorrow. Put your head on right. Think about it. Say now, “I’m going to war. It’s time to battle and I’ve just got to fight.” It’s a must. Just get on all your armor and say, “I’m headed out. I’ve got to do it.” Don’t think for once it’s going to be easy. Believe it or not, the first few days people thought it was fun. Then things began to drag on, get longer and longer. You start getting depressed, tired, sleepy, hungry. You want to lie down and rest. There’s no time for it. You got to think about all of that before you go out there. It’s not going to be easy, but you put your all-and-all on the line; it’s worth it. Think about it. You’ve got to do it for yourself. You’re in a war — either you get them or they will get you. It’s that simple.

Tags

June Rostan

June Rostan is a staff member of Highlander Center, where she does labor education. (1981)