Coal Employment Project

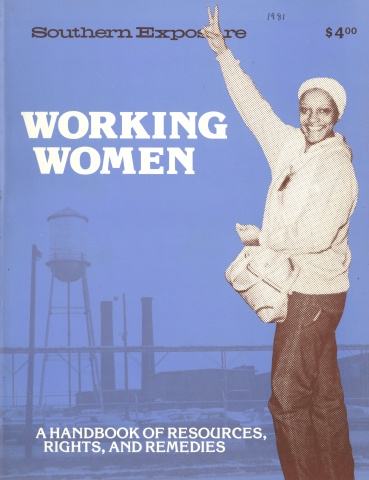

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 4, "Working Women: A Handbook of Resources, Rights, and Remedies." Find more from that issue here.

Thanks to a legal, organizing and media strategy, coal mining jobs have been opened to women.

The Coal Employment Project (CEP) is a story of success. In 1973, there were virtually no women miners. Today, there are over 3,000. The organization has grown from a one-person project of a public interest research group into an independent organization with a full-time staff of five. It publishes a monthly newsletter, runs training programs for women miners and is now developing a program to teach mine personnel how better to work with women miners. For the past three years, it has held an annual conference for women miners and their supporters. Having successfully gained access for women in the mining industry, it has increasingly turned its attention toward specific issues that affect women on the job: health and safety — especially reproductive hazards and rights — sexual harassment and child care.

Although it was paid scant attention by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) during its early efforts, a mailgram blitz by women miners and their supporters in 1978 resulted in the support by the Executive Board of the UMWA of a resolution to widen opportunities for women in the mines. In 1979 a similar mailgram campaign persuaded the union to pull its international convention from Florida because of the state’s failure to ratify the ERA. Approximately 35 percent of women miners attend union meetings as compared to 12 percent for male miners. Three women have been elected local union presidents, and last year nine women were among the 1,200 delegates elected to the international convention. Women members and their supporters are now pushing for a maternity/paternity clause in the union contract: new mothers and new fathers would be able to take up to two months' unpaid leave around the birth of a child.

Until now, CEP has concentrated on the Eastern coalfields, but as large-scale stripping of Western coal reserves appears more and more inevitable, it has moved to expand its base nationally. The newest women miners’ support team is the Lady Miners of Utah, and CEP plans to open a Western office. They also hope to establish ties with women in other mining industries such as malignium, potash and copper. In addition, CEP is turning to the international arena. Last year a delegation from CEP visited China, and the organization has begun to establish contacts with would-be women miners in several other countries.

Perhaps most importantly, CEP is beginning to transfer its model of attacking the coal industry to other industries. It is now cooperating with the Southeast Women’s Employment Coalition in a concentrated effort to apply its successful organizational and legal strategies to the nation’s road construction industry. However, since the cooperative road construction effort began in November, 1980, Executive Order 11246, the key to the CEP strategy, has been considerably weakened by the Reagan administration. The order places companies that hold federal contracts under an affirmative action obligation. Without 11246, hopes for the road campaign have dimmed, as have other possible industry-wide efforts.

The success of the organization is a tale of hard work, popular grassroots support and a group of smart women using whatever resources they could muster at the right time and in the right way.

It started in 1977 when an east Tennessee coal operator (and criminal court judge) responded to a request for a tour of an underground mine by the East Tennessee Research Corporation, a public interest group, by saying:

“Can’t have no woman going underground. The men would walk out; the mine would shut down. Now, if you fellows want to come, that is one thing, but if you insist on bringing her, forget the whole thing. ”

According to Betty Jean Hall, one of CEP’s founders, that “got people to thinking, ’’and the following day she received a call in Washington, D C., asking her to do a “little research. ’’ The following is her description of the efforts to build the Coal Employment Project.

The first thing we did was get the summary reports that all federal contractors are required to file with the federal government about their employment patterns. And sure enough, the most recent report showed that 99.8 percent of all coal miners were men, and that 97.8 percent of all people in the coal industry including secretaries and file clerks were men.

We then started tracking down the laws and how they were enforced; we came up with two or three that were really obvious. The one that really struck our eye was Executive Order 11246, a presidential directive which said that companies holding contracts with the federal government including TVA - which meant most of the mediumand large-size coal companies — are under an affirmative action obligation. Another was Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the state human rights acts. There are other protections, but these were the basic ones.

Executive Order 11246 appeared to be a way of attacking the whole industry. If that law were really being enforced, things would be very different from what they appeared on paper. We finally tracked down the official who was in charge of enforcing the executive order for the coal industry and he said, “Young lady, I can assure you there is no discrimination in the coal industry — race or sex.” That was the day I knew we were on to something!

But I didn’t know quite what we were on to, because I had a couple of concerns. I had grown up in eastern Kentucky and I never knew a woman who had expressed an interest in a coal mining job. We might have had a great legal case, but what was the point if there weren’t people who really wanted the jobs.

The second question I had was what we called the brute strength issue. You know, we still have those images of picks and shovels, and could the average woman really do the job? But we decided that there was enough that we had to explore and see what we were on to.

Within a couple of weeks I was getting more and more intrigued. After I had sent Neil McBride of the East Tennessee Research Corporation some of the basic information, he called and said, “Would you be willing to go on a fundraising trip to New York?” I had never done this in my life, had never been in a foundation, and had no idea about writing proposals. But we took off and went to New York to about five foundations. I will never forget going into the Ford Foundation with all of its brass stands for telephones! But it was a very comfortable situation for me because Neil had experience in this area and I was learning from him. We came away with a couple of good leads, and by mid-summer we had a grant of $5,000 from the Ms. Foundation to start the Coal Employment Project. That September I moved to Jacksboro, Tennessee, and spent the first few months tracking down some of the women miners we had heard about.

If I ever had any doubts about what we were on to, they melted away when I started meeting women miners. It became real clear to me that in the opinion of these women there were some jobs in the mines that some women couldn’t do; there were also some jobs in the mines that men couldn’t do, and there probably were no jobs in the mines that some women couldn’t do.

The other question I kept focusing on was: “Are you an exception to the rule? Are there other women here who would be interested in these jobs?” Invariably they would say, “I could tell you 50 women here tonight that would love to get these jobs.” When you asked the women where they got the idea to apply, they would either say, “I heard on radio or TV that the coal companies were going to have to hire women,” or, “Oh, I had a girlfriend who got a job in the mine and I figured if she could do it, I could do it.” We started realizing how important publicity was about these cases. The more publicity, the more women started thinking about it.

One woman that particularly impressed me was a woman named Mavis from eastern Kentucky. She had been married for a number of years, had four teenage children, and had recently been divorced and come home to eastern Kentucky. She had to get a job; she had no child support coming in. She got a job operating a posting machine in a bank and had a long drive each day to make minimum wage, and she soon realized that she was not going to be able to support four children on minimum wage.

She heard on television that a particular company was going to have to hire women, and she applied. She kept pursuing it, and going back demanding to know why she wasn’t being hired because she knew that men were being hired with no experience.

She went to talk to one official and he said, “Well, working in a mine is just too hard for a woman.” First she got mad, but then had to smile, thinking about the time when her two youngest were in diapers and they had no indoor plumbing. And she told him, “If you can imagine taking two babies and diapers down to wash in the stream and bringing them back every morning, don’t you think I have worked in conditions as bad as a muddy mine!” And she got the job.

She told me about the tension the first day she went to work, and that clearly nobody wanted her on their crew. Finally she spotted a fellow she had gone to high school with and said, “Look, you’ve got five kids; I’ve got four. I think I can do this job. If I can’t, I will get out, but I want to try it.” And he asked to have her on his crew. From that day forward for the first time in her life Mavis has had a job that she really enjoys. For the first time in her life she gets up and looks forward to going to work, and she is finally able to support those children in a way she feels good about. For her it has really been a good thing.

Mavis was the one that made me realize we were on to something important. From that evening on, there was no question in my mind about what we were doing.

In October of 1977, we started gearing up to file a big complaint with the Office of Federal Contract Compliance, the agency within the Department of Labor charged with enforcing Executive Order 11246. First I put together a study that documented the extent of discrimination against women in the coal industry. By May, 1978, we were ready to file our complaint. Based on what we had learned about the value of publicity, we held a press conference in Knoxville, Tennessee. We had two women miners there in their hard hats, steel-toed boots and safety belts, as well as a woman who had been trying to get a mining job — all explaining why they didn’t want their daughters and sisters to have to face the same kind of problems they were facing. Then we announced the filing of the complaint against 153 coal mines and companies that represented over 50 percent of the nation’s coal production. We asked the Department of Labor to do two things: investigate all the companies we had listed in our complaint, and target the nation’s entire coal industry for a concentrated review based on apparent patterns of sex discrimination documented in our study.

The New York Times carried the story; it hit the wire services and was in a lot of major publications. Within a matter of days we started getting phone calls and letters from women who had been trying to get jobs; it had never occurred to them that they had a legal case. Three weeks after we filed the complaint, the Department of Labor announced they would investigate our complaint company by company as well as target the entire coal industry for a concentrated review.

The first big settlement came in December of 1978 when Consolidation Coal Company, the nation’s second largest coal producer, signed a conciliation agreement agreeing to pay $370,000 in back pay to 78 women who had been denied mining jobs in Virginia, southern West Virginia and Tennessee.

We didn’t know any of these women at the time. The beauty of using the Executive Order is that it was the only route we could go without knowing exactly who these women were. The only way a small group like ours could take on the nation’s entire coal industry was to get the government to do our work for us. So we convinced the Department of Labor that we had a solid, valid complaint, that we had done a good bit of their homework for them, and basically developed their case for them. They took over responsibility for pursuing the complaint and negotiating a settlement with our input. The settlements are still coming down and the investigations are still going on. Other agreements and settlements brought on more and more publicity which got more and more women lined up for the jobs.

According to federal records, there was no such thing as a woman miner in this country until 1973, when the first woman was hired. In fact, we know that women worked as miners in small family operations during World War II and as gold miners in the 1800. But statistically speaking, there were no women miners.

When we started there were less than a thousand women miners — very scattered and isolated. The women that did work were generally the only woman on the crew, usually the first woman in the mine. They had virtually no contact with other women miners. We discovered as time went on that these women were facing incredible problems.

When I first went to Tennessee, I thought if we couldn’t get the government to take this over, there was nothing a couple of us in Tennessee could do. In fact, we discovered there was a heck of a lot we could do on our own, like helping women organize local support groups. We started getting phone calls from women a long distance away asking for help. We would say, “Are you the only one? Are other women having this problem?” Invariably, they would say, “No, it’s not just me, there is a whole bunch.” And we would say, “We can’t take care of this for you, but if you will get these women together, we will come and work with you to organize your own support group to solve your own problems.” That started happening a lot of places, and now a number of very active support groups are banded together into a larger, umbrella organization called the Coal Mining Women’s Support Team — Coal Employment Project’s sister organization.

We are one of the few organized groups in the country that has dealt with an entire industry. It was all done one step at a time. When we went on the first fundraising trip, we had never written a proposal. We’d never filed a complaint like this. We’d never done a press release. We had never put together a conference. We learned everything as we went. We realized early on that even with the federal government coming to bat for us, a small staff could never take on the entire nation’s coal industry. But with all those women out there, organized all over the coal fields, together we could do an awful lot!

Tags

Sue Thrasher

Sue Thrasher is coordinator for residential education at Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee. She is a co-founder and member of the board of directors of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1984)

Sue Thrasher works for the Highlander Research and Education Center. She is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. (1981)