“Our Government Wouldn’t Do This To Us”: Stonewalling Memphis Dump Victims

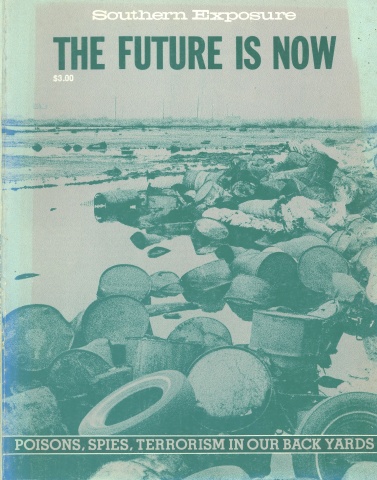

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 3, "The Future is Now: Poisons, Spies, Terrorism in Our Back Yard." Find more from that issue here.

Almost a hundred people were packed into a long, narrow room in the Frayser Community Center. The doors were shut to keep out noise from the adjacent gymnasium, and the television lights were blazing. The heat was almost unbearable. The debate, too, was getting hot. “If Alexander declares an emergency, it would make Frayser eligible for federal disaster relief funds,” said a man in his late twenties who was wearing a business suit and sitting in front of the room. “That’s why I’m saying we should go after Alexander.”

A woman in her thirties rose. “We may have to get arrested,” she said, “but I’m willing to do it for my children. That’s why I think we should do it, for the children.”

It was no small decision the residents of Frayser — and their friends from North Memphis — were prepared to make: the decision to sit in at the office of Tennessee Governor Lamar Alexander, to risk arrest. But these police officers, factory workers, hospital technicians, homemakers and teachers, most of whom had met for the first time only two weeks before at the founding meeting of the Frayser Health and Safety Committee, voted on the evening of February 22, 1980, to do just that.

They were scared and frustrated. Scared by the recent discovery that their own private hells — the illnesses that plagued their families — were in fact shared with their neighbors; frustrated because for two weeks they had been trying to get public officials to listen to their pleas for help. “We didn’t have any idea what to do,” recalls one Frayser resident.

The cause of their concern: chemical wastes, buried long ago underneath their homes, now leaking out and destroying their health. The story of the chemical contamination of the Frayser neighborhood — and the nearby community of North Memphis — graphically illustrates the increasing threat posed by past practices of improperly dumping hazardous wastes and the frustration that citizens across the country are facing in trying to protect their families from these wastes.

When James and Evonda Pounds bought a modest brick house on Steele Street in the Frayser section of northwest Memphis, they were glad to be moving. When they moved into it in January, 1976, they looked forward to having a larger house and yard, and living within walking distance of Evonda’s parents. “We thought it had a nice yard for the children to play in,” says Mrs. Pounds.

As it turns out, it was not such a nice yard. Once it was warm enough for them to play outside, the three children frequently came in with rashes, especially when it had been raining. Their daughter Sabrina developed respiratory difficulties as well.

“When I took them to our doctor, he told me their problems were being caused by chemical contamination,” recalls Mrs. Pounds. “Naturally I thought of stuff I had inside the house. But I had a locked pantry and that couldn’t be it. It was a while before I noticed that it was only after they came in from playing.” Armed with that knowledge, she went to the Memphis/Shelby County Health Department in August, 1976, her first of many trips.

For the next three years a tug-o-fwar ensued between Mrs. Pounds and the Health Department. In response to her complaints, the Health Department would take a few soil samples; several times the samples mysteriously “disappeared.” In 1977, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also ran tests. Both agencies told her that there were “trace amounts” of insecticides in her yard but that they posed no health hazard.

That Evonda Pounds kept going throughout these fruitless skirmishes is a tribute to her persistence, which she ascribes to simply “being stubborn” and worried about her children. “The more they said nothing was wrong when my doctor said it was chemical contamination, the more I wanted to do something,” she says.

Her suspicion that health officials were not telling the whole truth proved correct. The two chemicals that turned up most frequently, chlordane and heptachlor, are both carcinogens and dangerous even in small amounts. EPA banned both from most commercial uses, its hand having been forced by a 1975 lawsuit brought by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). Chlordane was found in concentrations ranging from two to 20 parts per million (ppm) in the Pounds yard, with a reading of 18.96 ppm under the swing set. As EDF community organizer Ruffin Harris says, “These were exactly the levels of chlordane we went to court to ban.” Yet the Health Department continued to maintain that the levels found in the Pounds yard were both safe and typical of Memphis, even after the Memphis Press-Scimitar published data from a 1970 EPA survey showing the background level of chlordane in Memphis is only 0.0138 ppm. EPA also refused to acknowledge the danger, even though its own data contradicted its public pronouncements.

The source of these dangers: “midnight dumping,” the practice of abandoning chemical wastes in deserted areas late at night. Usually, someone with chemicals to dispose of will pay a truck owner to take them away, saying the equivalent of “Forget where you got this.” In the 1940s and ’50s, before Frayser was developed, the area was a popular dumping ground for chemicals from the Velsicol Chemical Company and also, it is rumored, the Mallory Air Force Station. No one knows for sure what was dumped, but there is no longer any dispute that it occurred.

Across the Wolf River from predominantly white Frayser, the residents of predominantly black North Memphis were becoming equally concerned by the hazardous waste problem. In the midst of their community sits the Hollywood Dump, a formerly legal dumpsite used to bury chemicals produced by Velsicol. The dump site actually consists of two separate landfill operations. One, known as the “endrin pit,” is a mound of hazardous endrin waste containing sludge from a sewer-cleaning operation in the vicinity of the Velsicol plant. The other, located on the opposite side of North Hollywood Drive, contains a variety of hazardous pesticide wastes such as chlordane and heptachlor. State officials closed the dump in 1964 after Velsicol was implicated in a massive fish kill in the lower Mississippi River (see box).

Located on the banks of the Wolf River, the dump leaks chemicals into the river, making its fish unfit for human consumption. The Shannon Elementary School is located just beyond the Wolf River levee, and neighborhood children formerly used areas of the dump site as a playground; several children have drowned in the dump’s gravel pits.

In May, 1979, members of a local community group — the Cypress Health and Safety Committee — focused on the problems of chemical contamination from the Hollywood Dump. Led by long-time activist N.T. “Brother” Greene, the group had already successfully fought on issues ranging from blocking the nomination of a U.S. Court of Appeals judge to cleaning up raw sewage in the Cypress Creek. Securing the assistance of U.S. Representative Harold Ford, the committee pressured EPA to run tests at the dump site.

The results were frightening. If people thought the levels of chlordane in Frayser were high, those found in the Hollywood Dump were astronomical. EPA took a soil sample from the Shannon School playground and found 390 ppm chlordane, but later said the result was in error. Tests in the dump itself showed concentrations ranging from 170 to 5,000 ppm. (In Fall, 1980, a Vanderbilt University chemist found a “hot spot” that registered 500,000 ppm — a 50 percent concentration of chlordane!)

With this information in hand, the Cypress Health and Safety Committee tried to have the Shannon School closed, but the city refused to act. The committee continued to pressure the city to clean up the dump, and managed to publicize the issue to some extent — for instance, they found out that Nathan Tennessee was raising hogs for human consumption on the dump site itself — but it was apparent to many in the group that more allies were needed to get any action taken, and they began to look to Frayser for those allies.

Some members of the Cypress group were hesitant to work with whites from Frayser. Greene explained how he overcame this resistance: “One told me, ‘Those white folks just moved up to Frayser to get away from blacks. Why should we help them?’ I said to them, ‘The problem we are fighting in Hollywood is a very big thing. If we work together, we can get farther faster.’” Thus began the effort to forge a racially unified coalition to protect the residents of Frayser and North Memphis from the hazards of past chemical dumping.

VELSICOL: a Record of "Known Ecological Abuses"

The name of the Velsicol Chemical Company pops up again and again when the subject is irresponsible disposal of hazardous wastes. It’s the company behind the Hollywood Dump described here, the Hardeman County dump responsible for Nell Grantham’s troubles (see interview on page 42) and countless others.

Velsicol is a wholly owned subsidiary of Northwest Industries, a holding and management company. It manufactures and sells a variety of specialty pesticides, resin products, industrial chemicals and other chemical products, and has plants in Arizona, Illinois, Mexico, Tennessee and Texas. The wastes produced have found homes all across the South. After abandoning the Hollywood Dump in 1964 and the Hardeman County dump in 1972, says Nell Grantham, “They went right into other parts of Tennessee to dump — one of those places is Bumpass Cove, Tennessee. I know they have dumped in South Carolina, North Carolina, Alabama — all through there.”

The Memphis plant, opened in 1932, employs 250 people. It was implicated in a massive fish kill in the Mississippi River in 1964: more than five million fish from Memphis to New Orleans died as a result.

Michael Brown, the reporter who broke open the Love Canal disaster at Niagara Falls, has looked into Velsicol’s activities in his book Laying Waste: The Poisoning of America by Toxic Chemicals. He found the company to be second only to Hooker Chemical (the company responsible for Love Canal) in involvement in “known ecological abuses.” Its record, he says, ranged from the fish kill to “illnesses among plant workers in Texas. In Michigan, flame retardants from a firm it purchased had found their way into livestock feed, leading to the destruction of animals across the state. In Memphis, it was suspected that toxic emanations from its plant had caused employees of the municipal wastewater treatment plant to fall ill. . . . The company once refused to comply with a federal request to call back two chemicals, and in 1976 it was publicly chastised by a United States Senate committee staff for permitting the further production of a pesticide, leptophos, after it appeared obvious that workers were becoming ill in its vicinity. . . .

“Controversy flared highest around Velsicol’s manufacture of chlordane and heptachlor. Since 1965 heptachlor, along with its epoxide, had been suspected of causing cancer in mice. Velsicol claimed otherwise. . . . On December 12, 1977, a special grand jury returned an 11-count indictment against the company and six of its past or present officers, employees and attorneys, charging that from August, 1972, to July, 1975, the defendants had conspired to defraud the government, concealing material facts indicating that the substances induced animal tumors. The charges were later dismissed.”

In January, 1980, Brother Greene visited Evonda Pounds with Ruffin Harris, who had come to Memphis to help the Cypress group on behalf of the well-respected Environmental Defense Fund. Harris advised Greene and Pounds to conduct a door-to-door survey to establish the extent of the health problems in Frayser, as had been done at Love Canal. Two reporters who had followed the issues closely — Tracey Wilkes of WMC-FM and Leonard Novarro of the Memphis Press-Scimitar — were recruited to help with the survey.

Going door to door in one of Memphis’s colder winters, the surveyors heard the same stories over and over again. “I knew other people had problems similar to mine,” says Pounds, “but I didn’t realize how widespread it was until that day.” Adds Wilkes, “It got really scary.” In a single block, 26 out of 28 people interviewed had symptoms possibly related to chemical contamination, and there had been at least three cancer deaths in the past two or three years.

One man in his seventies was at first skeptical of the idea that chemicals were a problem. Oh, he had to paint his house every two years, he said, because the paint kept peeling off, and a few trees had died in his yard. Then there were the allergies that had begun when he moved into his home five years ago. But he didn’t think they had anything to do with chemicals. The surveyors moved on. A half block later, they looked back and saw the man panting after them. His breathing, he said, he also had been having trouble with his breathing, but he hadn’t really thought much about it. House after house: tumors, breathing problems, rashes, cancer. One by one the Frayser residents recounted their illnesses.

The political impact of this and subsequent surveys was even greater than their psychological impact. The stark figures on how many people were sick were enough by themselves to establish that something was wrong in Frayser. When just under half the people interviewed in a one-block area have cancer and three-quarters have breathing problems, as Novarro later found, health officials have some explaining to do.

Bolstered by the daily news media features on Frayser, Greene, Pounds and Harris used the contacts made during the survey to pull together a Frayser Health and Safety Committee. Meeting jointly with the Cypress committee, the organization held its tumultuous inaugural meeting on February 7, 1980. One hundred and thirty people attended, and about 20 testified about their illnesses with TV cameras rolling. Early on there were attempts to create divisions in the group: city council member Glenn Raines denounced Brother Greene as an outsider to the neighborhood who had never shown any interest in it before. However, a member of the audience quickly retorted, “And where have you been for the last four years, councilman?” The speaker, Jane Hensel, was elected the group’s president. The members also decided to meet the next day with County Mayor William Morris.

The meeting with Morris seemed to be a promising beginning. The members of the delegation told him their stories one by one. The accounts “seemed to make an impression on him,” recalls Billie Jean Rochevot. “He promised to help and come out to Frayser the next day.” Besides that, Morris told the press he thought as many as 25 to 30 families would have to be relocated. But in about 10 days his promises had evaporated, and no further offers of help came from his office.

However, the Frayser Health and Safety Committee continued to attract new members afraid for their own health. Rochevot herself responded immediately to the press coverage of the committee’s first meeting. A 31- year-old police officer, she has personally suffered greatly from the chemical contamination: “I’m very bitter; I lost my ability to bear children three years ago. My daughter is five. When she plays out in the dirt her hands get infected. She has lost a thumbnail twice, and one of her toenails once. Once I stayed up for two straight nights with her. She couldn’t breathe. She had a rash all over her chest. You can’t keep your children inside all the time.”

With support swelling from others like Rochevot, the Frayser committee became impatient to get some immediate action taken. In a joint meeting with the Cypress Health and Safety Committee, they targeted Governor Alexander to have him declare Frayser a disaster area and make it eligible for federal disaster relief funds. The committee took a bold step in the tactics of direct action, choosing to sit-in at the governor’s Memphis office to force a meeting with him.

As the State Office Building opened on February 25, about 40 members of the Frayser Health and Safety Committee went to the top floor and took over the outer portion of the governor’s office. Alexander was not even in the state, but in Washington for a meeting of the National Conference of Governors; the demonstrators knew this fact, but were hoping to stimulate some action from him anyway. However, Alexander either did not hear about the protest or simply refused to speak with them; to this day, the demonstrators do not know which. The group settled in for a potentially long stay, but the 15 people who had vowed to stay overnight were arrested shortly after the building closed for the night; the charges were later dropped, and the group received no response to their requests at all.

Recalls Rochevot: “The sit-in was a desperate attempt to get the attention we deserved. We had this feeling that if we’d been Hein Park or Germantown [wealthier Memphis neighborhoods], we would have gotten somebody’s attention, but here we were, residents of a middle- and lower-class neighborhood. It was as if we were unimportant. Finally, we said, ‘We’re going to get his attention if it takes going to jail.’”

Even if Alexander was unwilling to assist them, the publicity the Frayser and Cypress committees had generated finally brought some responses from government officials. Under constant pressure to “come up with something,” the Health Department announced that it had found witnesses to illegal dumping in Frayser in the 1940s and ’50s. At almost the same time, EPA announced that there had been no dumping in Frayser, a claim it later retracted. Despite this contradiction, the two agencies were of one voice in assuring the community that the levels of chemicals found in Frayser were neither dangerous nor unusual. Evidence to the contrary was ignored.

The group did receive some solid support from one government official — U.S. Representative Harold Ford, whose congressional district included the Hollywood area but not Frayser. According to Ruffin Harris, “Ford got on board first, it took the least pressure to get him on, and he’s been good all along.” Specifically, he kept after the EPA to intervene, and he was instrumental in having hearings called by House Investigations and Oversight Subcommittee member Albert Gore, Jr.

As a result of such pressure, EPA embarked on a more ambitious testing program encompassing air, water and soil samples, and the federal Center for Disease Control surveyed Frayser residents and residents of a control neighborhood in northeast Memphis to compare disease incidence.

Nevertheless, the EPA still refused to take strong action to clean up the situation. Though it started more testing, it confined the testing to a tightly restricted area. When a barrel was unearthed from one resident’s yard, EPA whisked it away and later announced it was empty, despite eyewitness accounts to the contrary. Test results throughout the neighborhood showed dangerous levels of chlordane and other chemicals, but these were again dismissed as “trace amounts.”

Finally, in response to Representative Gore’s hearings in April, 1980, EPA created the Metropolitan Environmental Task Force — labeled by community residents as the “Task Farce.” This 25-member board was appointed to advise EPA on environmental problems in Memphis, particularly those related to Hollywood and Frayser. It included public officials, Jaycees, the Rotary Club — but only three residents of the affected neighborhoods. EPA added five more residents to the Task Force after an outraged protest at the first meeting of the group, but ignored the demand that at least 50 percent of the Task Force consist of victims. Eventually, opposition to the Task Force grew so strong that Brother Greene was arrested at a meeting and many area residents left in a huff.

The only significant concession the EPA would make was to place a fence around the Hollywood dump — and that only happened as a result of pressure from Ford and Gore. Even the Task Force had little power to influence EPA’s action. When it finally decided to clean up some of the Hollywood Dump’s “hottest” spots, EPA put together a “Technical Group” to deal with the problem consisting of itself, the Health Department — and the Veisicol Chemical Company. The Task Force had no say in how the dump’s hot spots were to be cleaned up.

The still-unfinished cleanup of the Hollywood Dump's hot spots is the only such effort undertaken by EPA in Memphis. The agency maintains to this day that it has no evidence to justify individual health testing in Frayser or to say that toxic chemicals have been found there in significant amounts. Thus, from EPA’s standpoint, “cleaning up” Frayser is not only unnecessary, but meaningless. The frustration this caused among Frayser residents is understandable. As one explained, “One thought just kept going through our minds. Our government wouldn’t do this to us. It was hard for many of us to face the fact that our government was doing this to us.”

As the level of frustration grew in response to continued government inaction, the initial cohesion and commitment of the Frayser and Cypress Health and Safety Committees waned. Part of the problem was the hotly debated sit-in. The entire experience was anti-climactic and accomplished little while dividing the group significantly. People began missing committee meetings, apparently feeling that nothing was being accomplished. In addition, personality conflicts mounted within the Frayser leadership itself. Jane Hensel resigned as president and was replaced by Billie Jean Rochevot. Hensel claims that Rochevot forced her out; Rochevot retorts that Hensel quit.

Tensions also existed between Greene and the Frayser leadership. Greene attributes the split to racial tensions; members of the Frayser group alternately claim that blacks are either still active in the organization or “are more comfortable with other groups that are mostly black.” One Frayser resident goes so far as to call Greene a racist, saying, “He makes blacks feel guilty for going with the whites.”

The Cypress and Frayser committees have ceased meeting together, and though they have continued, by necessity, to work cooperatively on some projects, relations between the two groups are clearly strained.

The Cypress group has dropped out of the “Task Farce” and moved on to other issues. The Shannon School is still open.

After the sit-in, a third community group became involved: ACORN, the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now. Black ACORN members in the Northside Manor Apartments, just north of Steele Street, were incensed when the housing project was excluded from the EPA’s testing area. “We were dead set on getting the apartments included,” says Anne Jefferson, the group’s chair. But when their main demand, individual health testing, was ignored by EPA, ACORN too fell by the wayside, going on to more winnable issues.

The Pounds family now wants to move out of Frayser. “It took us a long time just to get an agent,” says Evonda Pounds. “Now when he tells prospective buyers it’s on Steele Street, they say, ‘No, thanks.’”

Pounds has grown discouraged with the whole effort to seek a solution to the problem. She long ago quit going to Frayser Health and Safety Committee meetings, and now expects nothing more than more bad news. Her doctors have found evidence of liver and kidney damage in her, and of chromosome damage in her children. In early 1980, hardly a day went by for her without hearing from a reporter. Now she never knows what “great news” she’ll get next.

Tags

Kenny Thomas

Kenny Thomas, a former ACORN organizer, is a free-lance writer whose articles have appeared in The Guardian and In These Times. Portions of this article are based on an earlier article he wrote for the October, 1980, edition of Memphis magazine. (1981)