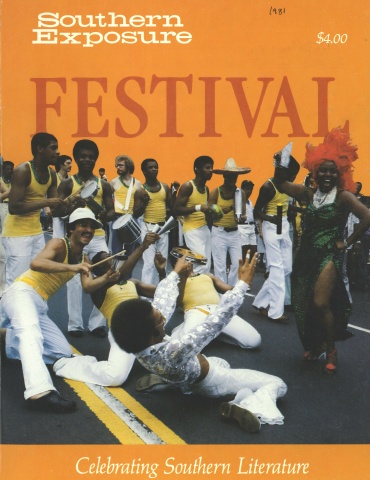

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

I did not know the word “homosexual” until I was 12 and read an article on the subject in Life magazine. It worked on me like a silent bombshell: this revelation that a whole group of people — enough for there to be a word for it — were powerfully drawn to members of their own sex. As I looked at Life's sinister pictures of sad, scared men walking down long, dark, deserted streets, I saw that those feelings echoing, reverberating in me meant a life of loneliness and alienation. This knowledge overwhelmed me, so that I pushed it to the back edge of my brain, where I developed a secret homesickness — maybe I had always had it — for these people I could love, a conviction that some day I would find them. I told myself in private conversations that I had to “get away from home” (Alabama, the 1950s) to “be myself;” I figured it meant somewhere far away and very exotic — like London, England, or an island in the Caribbean. I resolved to travel. I got as far as Durham, North Carolina.

When I fell unmistakably in love with another woman, in Durham, in 1973 (at the age of 24), I was not sure that I had come far enough for this. But my brain was in open rebellion, not to mention the entire rest of my body and spirit. I sneaked over to the Intimate Bookstore in Chapel Hill to see what books they had on the subject (I had developed a habit of approaching books first, then proceeding sometimes to life). I was afraid to go to my favorite bookstore in Durham, because someone I knew might see and tell. So I bought the only books that had “lesbian” in the title and went to sit beneath the trees by the stone wall on Franklin Street. I read with a sinking heart as a clinical voice explained how lesbian lovemaking, and love, was basically “hollow” because there was no penis to insert into the lesbian vagina. That turned out to be the biggest lie I ever got told, but I sure didn’t know it then.

So when I went to my first Southeastern Gay and Lesbian Conference in Chapel Hill in 1977, I headed directly for the session on lesbian literature. There sat a whole roomful of lesbians, including two novelists (Bertha Harris and June Arnold, flown in from New York) and Catherine Nicholson and Harriet Desmoines, the editors of a lesbian magazine in, of all places, Charlotte, North Carolina. It was like coming home.

Now this literature I stumbled into was very different, you had better believe it, from what I had been reading while struggling to acquire a Ph.D. in English. In graduate school, other miserable graduate students and I spent long hours of research on literary history, theory, symbolism and all, wondering over lunch in the cafeteria, day after day, why we put up with the sadomasochistic tactics of professors, why we and they were doing what we did. In my courses on twentieth century literature, I learned about how Ezra Pound invented “modernism” in the early part of the century and then forced it on everybody else because, as he explained, there was nothing new to say, only new ways to say it. His buddy T.S. Eliot went on to define poetry as the “escape from emotion.” With these two men, literature took a great leap into academic obscurity, from which only scholars called “New Critics” could hope to rescue it. The modern writer became a suicide. As A. Alvarez’s book The Savage God documents, writers jumped off boats and bridges, blew their heads off with shotguns or stuck them in ovens, or slowly and loudly drank themselves to death. Most of the “great works” of this century traced the dissolution of Western white male culture, by male writers who could only identify with its demise. Just listen to the titles: The Wasteland, “The Second Coming,” Autumn of the Patriarch, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Love Among the Ruins. As graduate students, we sat around in despair trying to explain all this and lamenting that our own students, whom we taught as teaching assistants, didn’t lap it all up as we did — a failing we pompously explained as the “decline of literacy.”

With lesbian literature, I suddenly understood — perhaps remembered — how it’s supposed to be. No lesbian in the universe, I do believe, will tell you there’s nothing left to say. We have our whole lives to say, lives that have been censored, repressed, suppressed and depressed for millennia from official versions of “literature,” “history” and “culture.” And I doubt that many lesbians will tell you that poetry, or anything else, should be an escape from emotion. We have spent too much of our lives escaping our emotions. Our sanity has come when we turned to face them. The lesbian’s knowledge that we all have stories to tell and the ability to tell them lessens the suicidal modern alienation between “writer” and “audience.”

Lesbian literature — like all the best women’s writing today — is fueled by the knowledge that what we have to say is essential to our own survival and to the survival of the larger culture which has tried so hard to destroy us. The lesbian’s definition of herself is part of the larger movement by all women to define ourselves. It is a movement with such tremendous revolutionary potential that it has scared the bejesus out of just about everybody in the past decade. (Even the forces of reaction rally to protect their narrow version of “the family” - which is anti-feminist and anti-gay.) I am now teaching a survey of British literature using the Norton Anthology, and for its first thousand years not a single woman’s voice can be heard — though it is filled with plenty of usually hostile male definitions of what women are. When we women begin to define ourselves, then much of conventional literature (not to mention the rest of society) must be redefined, rejudged. Nothing left to say? My god.

So what does all this have to do with Southern literature? Potentially a lot. Southern literature is on the same dead-end track as the rest of the patriarchal culture. Essays often deal with questions like “Is the Southern novel dead?” and “Is there writing after Faulkner?” Well, I think there is. As Southern women writers redefine ourselves, a new literature could emerge. As Southern lesbians (and gay men) redefine ourselves, new insights emerge from a culture that show the worst features of American society writ large. (Oppression in the South has always been on the surface and easy to see.)

Southern lesbian literature can be traced back to the beginning of the century. It is a largely unacknowledged aspect of the “Southern Renaissance,” that burst of creativity beginning in the late 1920s when Southern writers finally began to look critically at their own culture. It extends into the ’60s wave of liberations: black civil rights, women’s and homosexual liberation. And now, for the first time, some Southern lesbian writers are dealing with Southern lives and Southern themes in openly lesbian voices, in widely varying styles. What we have to say is important, and other Southerners should listen.

Stage One: “Lines I dare not write”

Angelina Weld Grimké, Carson McCullers and Lillian Smith are the earliest Southern and lesbian writers I can locate. Among them, they raise themes that later lesbians either develop or redefine. Angelina Weld Grimké was the daughter of Archibald Henry Grimke, the slave nephew of the abolitionist Grimke sisters from South Carolina. She grew up in Boston and lived in Washington, D.C., from 1902 until 1926. Her love poetry establishes her lesbianism and shows the selfsilencing that accompanied it — like this from “Rosabel”:

Leaves that whisper whisper ever

Listen, listen, pray!

Birds that twitter twitter softly

Do not say me nay

Winds that breathe about, upon her

(Lines I do not dare)

Whisper, turtle, breathe upon her

That I find her fair.

“Lines I do not dare” — when a lesbian denies her self and denies her sexual energy, she denies her creative energy as well. Feminist poet and critic Gloria Hull finds these lessons in Grimké’s life:

The question - to repeat it - is “what did it mean to be a Black Lesbian/poet in America at the beginning of the twentieth century? First, it meant that you wrote (or half wrote) - in isolation - a lot which you did not show and knew you could not publish. It meant that when you did write to be printed, you did so in shackles - chained between the real experience you wanted to say and the conventions that would not give you voice. It meant that you fashioned a few race and nature poems, transliterated lyrics and double-tongued verse which — sometimes (racism being what it is) - got published. It meant, finally, that you stopped writing altogether, dying, no doubt, with your real gifts stifled within - and leaving behind (in a precious few cases) the little that man ages to survive of your true self in fugitive pieces.

Grimké, who felt herself “crushed” and “smothered . . . under the days,” has received little critical attention, no doubt because of her triple jeopardy — she was black, female and lesbian.

The next two women I find are Lillian Smith and Carson McCullers. Writing in the Southern Renaissance, these two white women also adumbrate themes and traits that emerge more fully in later Southern lesbian literature. Like Grimké’s, their lives and work show the effects of lines they “dare not write.” They also illustrate further the kinds of problems that lesbians encounter in trying to reconstruct their culture.

For instance, neither woman ever publicly defined herself as a lesbian, and both might be upset that I am now proceeding to do so. A recent biography of McCullers, The Lonely Hunter, by Virginia Spencer Carr, establishes McCullers’ emotional ties with women, albeit in a disgustingly heterosexist way: “Reeves [Carson’s husband, probably bisexual himself] was incapable of coping with his or his wife’s sexual inclinations or of helping her to become more heterosexually oriented. Carson was completely open to their friends about her tremendous enjoyment in being physically close to attractive women. She was as frank and open about this aspect of her nature as a child would be in choosing which toy he most wanted to play with” (my emphasis).

Identifying Lillian Smith as lesbian presents more complex problems. As yet, there is no definitive biography, though there is the fact that she never married and that she lived and worked with a woman “companion” for decades. There is no way to prove a sexual relationship between them, nor is there a need to do so. This puritanical culture defines homosexuality as sexual activity only, so that it can then self-righteously condemn it, rather than seeing homosexuality as a question of emotional identity. (It’s harder to be self-righteous about telling people they can’t be who they are or love whom they need to.) I am sadly certain that many lesbians have lived out their entire lives fearing and repressing their sexuality. Smith’s commitment to women, her analysis of oppression and the nature of her criticism of her surrounding culture are enough to show me her lesbianism. But my best argument comes from my gut — a sixth-sense way by which lesbians have always known each other, a way of knowing not given much credence by most literary scholars. And, in treating only two women from this period, I am being fairly discreet. For example, if Flannery O’Connor, of whose sex life there is no public record, cannot be put clearly into a “lesbian” column, it makes no more sense, and maybe less, to consider her “heterosexual.” Her letters show that her closest emotional relationships seem to have been with women.

The lives and work of McCullers and Smith present instructive contrasts in white lesbian response to a repressive culture. McCullers, for most of her adult life, acted out what I believe was lesbian alienation (which is to say internalized homophobia) without the political insights into the culture she wrote about, insights so important in Smith’s writing. Internalizing the values of a culture that pretends that only men can love women, Carson once wrote to a friend: “Newton, I should have been a man.” She thought of her attraction to a female friend as “the devil at work” in her. She entered into a horrible marriage with a bisexual man and spent most of her adult life in self-destructive confusion.

It is little wonder that loneliness and displacement suffuse her writing and are seen as cosmic. I am not saying that all kinds of people are not lonely. But, as a lesbian, I know that we are lonelier than we have to be and that structures of society separate us unnecessarily. This aware ness of the way patriarchal power structures limit people is absent in McCullers’ writing, making many of her characters — and their creator — embrace the grotesque.

Lillian Smith is always interested in why and how people get warped. For 20 years she and Paula Snelling published South Today, one of the most outspoken, radical voices to oppose segregation in the ’40s and ’50s. Her Killers of the Dream is the most profound analysis I know of the causes and effects of racism on the whites who practice it. Smith’s life and writing embody what later became the feminist manifesto: “The personal is political.” She delved into her own life as a white Southern female and came up with a radical analysis of Southern — and of Western — culture, an understanding of the powerful links between sex, Christianity, economics and politics. But, unlike McCullers, Smith never lost her vision of personal and cultural wholeness, nor stopped searching for “how to make into a related whole the split pieces of the human experience.” This vision gave her hope for change. It made her into not only a writer but a radical and brought her into conflict with her whole culture. When she wrote, she put her life on the line. Her house was burned three times. But she proceeded to develop not only an anti-racist but a feminist analysis, seeing and establishing connections among the culture’s various virulent forms of oppression.

Smith’s analysis seems to me to proceed out of a South ern lesbian sensibility. Her main theme is repression. Influenced by Freud, she discusses the “hidden terror in the unconscious,” and she traces the ways white culture built itself on lies, “A system of avoidance rites that destroyed not bodies but spirits.” Her fiction gets its energy from exploring sexual taboos: One Hour tells the story of a doctor accused of molesting a child. Strange Fruit is the story of a tragic relationship between a black woman and a white man. In Killers of the Dream she analyzes “ghost relationships” between the races: white man/black woman, white father/unacknowledged child, white children/black “mammy,” I can’t help thinking she was sensitive to these because of the ghost relationships in her own life, between woman and woman, that she used Strange Fruit to explore obliquely.

Among them, Grimké, Smith and McCullers introduce themes and concerns that figure in later Southern lesbian writing and life: repression, the triple jeopardy of the black lesbian, the concern in both black and white work with the grotesque, the need for a political understanding to preserve life and sanity, and awareness (in Smith, at least) of the interrelatedness of oppressions. Angelina Grimké died in 1958, “flattened” and “crushed” — to borrow Hull’s description. Lillian Smith died in 1964, in the midst of an energy for social change that was sweeping the South and that later would bring change to the rest of the country. It is from this burst of liberating energy, unleashed by black Southerners who said “no” to white racist ways, that the second generation of Southern lesbian writing emerges.

The ’60s and ’70s

The ’60s brought what Grimké, Smith and McCullers had needed desperately: a feminist analysis of a sexist society that gave lesbians support and a basis for self-respect. As Sara Evans shows in her recent book Personal Politics, feminism first burst forth in the urban centers — New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Washington — but its roots were in the Southern Civil Rights Movement. There white women gained skills and self-respect (especially from examples set by Southern black women) but were denied roles commensurate with those skills by the male leadership as the New Left exited the South and took on Vietnam. In 1967 New Left women in Chicago pulled out to form the first autonomous women’s group working solely on women’s issues. By the next year this feminist movement had spread to New York and other major cities. In 1969 gay people rioted against police in Greenwich Village and the gay movement took off too. Lesbians gradually emerged in and out of women’s and gay liberation. An autonomous lesbian-feminist movement and analysis developed as lesbians began to define themselves, working not only on broadly based feminist issues, but also on rediscovering, extending and preserving a culture nearly obliterated by centuries of misogyny and homophobia.

Little of this took place in the South, but Southern emigrants to Northern and Western cities helped create this emerging lesbian-feminist analysis and culture. Like black people, lesbians — both white and black — had left the South in large numbers looking for increased freedom and safety. Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle, a much-loved lesbian novel of the early ’70s, traces the archetypal journey from the deep South to New York. Her departure is precipitated by the “apple-cheeked, ex-marine sergeant” dean of women at Florida State, who accuses the first-year woman of seducing “numerous innocents in the dorms,” various black women and men, and the president of Tri-Delta sorority. Rita Mae’s departure is probably characteristic of many other Southern lesbians who found themselves no longer welcome at home.

In the cities to which they migrated - especially New York and San Francisco — Southern lesbians such as Ti-Grace Atkinson, Rita Mae Brown, Pat Parker and Judy Grahn benefited from and helped give birth to the emerging movement. In New York Atkinson and Brown both bolted from the local National Organization for Women. Atkinson left protesting NOW’s hierarchical organization and soon helped form a group called the Feminists that went a long way toward articulating male oppression of women. She was also concerned with clarifying and purifying women’s relationships with one another. The Feminists, influenced by socialism, tried to develop an egalitarian process within their collective. This dual focus — on men’s oppression of women and on women’s “lateral oppression” of one another — is characteristic of much lesbian-feminist analysis.

When Brown left New York NOW, the issue was its treatment of lesbians, and she went on with others in New York and Washington to found lesbian separatism. With Barbara Love, Sidney Abbott and March Hoffman, she wrote The Woman Identified Woman, articulating why lesbianism is a feminist issue, why feminists cannot exclude lesbians from the women’s movement. As she wrote: “What is a lesbian? A lesbian is the rage of all women condensed to the point of explosion. She is the woman who, often beginning at an extremely early age, acts in accordance with her inner compulsion to be a more complete and freer human being than her society — perhaps then, but certainly later — cares to allow her. ... It is the primacy of women relating to women, of women creating a new consciousness of and with each other, which is at the heart of women’s liberation, and the basis for the cultural revolution.”

That women can and do love each other, that this love is an extension of loving self-respect, should not be so revolutionary an idea. But in patriarchal society it is. Brown went on to put the manifesto into practice, moving to Washington and forming, with 11 other lesbians, the Furies collective, a “bolshevik cell” of lesbians working together for revolutionary change — living together, sharing chores equally, sleeping on mattresses on the floor in the same room. In the first issue of The Furies newspaper, Ginny Bernson announced the group’s intentions: “We want to build a movement in this country which can effectively stop the violent, sick, oppressive acts of male supremacy. We want to build a movement which can make all people free.”

It was a decade of manifestoes, of huge intentions. Within two years the Furies had dissolved, split internally by class differences, but also by the magnitude of the problems they had taken on. “Change,” Brown reflected later, “is not a convulsion of history but the slow, steady push of people over decades.” When the Furies disbanded, many of its members went on to contribute to the growing network of lesbian presses, newsletters and journals that I stumbled across in 1977. This lesbian-feminist “cultural revolution” is the “slow, steady push” that survived the convulsions of the late ’60s and early ’70s.

“Women’s art is politics, the means to change women’s minds,” June Arnold explained in an interview in Sinister Wisdom in 1976. Feminism, like Marxism, seeks to ally art and politics. And lesbian-feminists soon realized that, to create our own networks to subvert patriarchal culture, we would have to seize some of the means of producing books. Southerners helped create a network of feminist presses and journals that emerged in the mid-’70s. For example, North Carolina novelist June Arnold, with Park Bowman, founded Daughters, Inc., in Vermont in 1972 to specialize in feminist novels. (In its eight-year history, Daughters published many books by Southern lesbians.) Arnold summarizes her sense of lesbian literature gained from reading manuscripts submitted to Daughters: it is “a collective genius, coming from one woman’s poem, another’s comment, a scene from a chapter of a novel. I think we are all in the process of writing together.”

Meanwhile, out in San Francisco, four lesbian poets set out to revive “a militant tradition of feminist writing on the west coast.” Two of these women, Pat Parker and Judy Grahn, were refugees from Texas. The white lesbian, Grahn, explains of her black lesbian friend:

Our lives are parallel in some ways. We are both from the Southwest. ... We both had ugly tin roofs and no room to wave your arms, in a country vast with space. We were both miniature cowboys in boots and big imaginations. We knew it was impossible for us to enter the world of poetry ... and consequently we invented another world of poetry and became peers, and leaders, and friends.

The world of poetry they invented, the language they reclaimed, is the “common language” of the “common woman,” not the highly obscure and allusive language of much of modern poetry. In one of Grahn’s poems,

the common woman is as common as the best of bread and will rise.

It is a language that can state the truths of women’s lives with sometimes brutal, always loving simplicity. With it Grahn and Parker helped reshape the meanings of “lesbian” and “woman.” As Grahn proclaimed at the beginning of her collected poems:

look at me as if you have never seen a woman before

I have red, red hands and much bitterness

The poems of Grahn and Parker make it clear that a lesbian is primarily a woman who loves other women; in a world where women are not valued, are often maimed and killed by men, it is a love that brings great vulnerability and great anger. Grahn and Parker both wrote long, wonderful autobiographical poems out of this vulnerable anger and love. Grahn’s “A Woman Talking to Death” rose out of her seeing a young man killed in a wreck on the San Francisco bridge, hit by a black man in a car when his motorcycle stalled. “I’m afraid,” said the man whose car killed the boy, “stay with me, / please don’t go, stay with me, be / my witness.” Grahn says, “I’ll be your / witness — later.” Afraid, she leaves (“as I have left so many of my lovers”) and later finds out that white cops beat the black man and that white courts sentenced him to 20 years “instead of life.” This experience leads her to meditate on how she would bear witness to her own interrogation:

have you ever kissed other women?

Yes, many, some of the finest women I know, I have kissed, women who were lonely, women I didn’t know and didn’t want to, but kissed because that was a way to say yes we are still alive and loveable, though separate, women who recognized a loneliness in me, women who were hurt, I confess to kissing the top of a 55 year old woman’s head in the snow in Boston, who was hurt more deeply than I have ever been hurt, and I wanted her as a very few people have wanted me - I wanted her and me to own and control and run the city we live in, to staff the hospital I knew would mistreat her, to drive the transportation system that had betrayed her, to patrol the streets controlling the men who would murder or disfigure or disrupt us, not accidentally with machines, but on purpose, because we are not allowed on the street alone.

Pat Parker’s “Womanslaughter” is a similar meditation on the murder of her sister by her sister’s husband. The literary inspiration for the poem was Parker’s reading of Grahn’s “A Woman Talking to Death,” a poem Grahn says her friend Parker “understood before I did.” Parker’s poem rages against the murderer, her brother-in-law, who got off with one year for “manslaughter” since his was a “crime of passion;” but the poem spirals out to include the lives of all her sisters:

Men cannot rape their wives.

Men cannot kill their wives.

They passion them to death.

. . .

I have gained many sisters.

And if one is beaten,

or raped, or killed,

I will not come in mourning black.

I will not pick the right flowers.

I will not celebrate her death

& it will matter not

if she’s Black or White –

if she loves women or men.

I will come with my many sisters

and decorate the streets

with the innards of those

brothers in womenslaughter.

Gone is the lesbian-as-grotesque, the lesbian isolated and alone. In Grahn and Parker the lesbian moves in the strength, the power, sometimes in the despair, of her love for other women.

Parker’s poems also explore her identity as a black woman, a black lesbian. Gloria Hull wrote of Angelina Grimké: “Black, woman, lesbian, there was no space in which she could move.” Pat Parker’s poetry shows her creating her own space, empowering herself as a black person, a lesbian, a woman. She claims the strength of “the black woman . . . child of the sun, daughter of dark . .. survivor.”

Parker also speaks to white lesbians who oppress her: “SISTER! Your foot’s smaller, / but it’s still on my neck.” Advice “for the white person who wants to know how to be my friend”: “The first thing you do is forget that i’m Black. / Second, you must never forget that i’m Black.” Parker is a woman who must deal with multiple vulner abilities: a black family that talks of “bulldaggers;” white lovers who evoke bitter memories of racism. Grahn’s and Parker’s poems show lesbians clearly: to hide our anger from one another, to hide our vulnerability to one another, is to deny our strength. Meanwhile, in the South in 1976, two lesbians in Charlotte — Catherine Nicholson and Harriet Desmoines — began Sinister Wisdom, a magazine that was to become the main vehicle for lesbian writing in the late 1970s. The writing that emerged in Sinister Wisdom was a response to Catherine and Harriet’s call for lesbian vision, “that of the lesbian or lunatic who embraces her boundary/criminal status, with the aim of creating a new species in a new time/space.”

Brown, Arnold, Harris, Parker, Grahn, Nicholson — all are Southerners. But they were not acting or writing as Southerners in the late ’60s and ’70s as a new movement emerged. They were lesbians first and always (except probably for Parker, who was black and lesbian), working to give birth to themselves and to a lesbian movement, a women’s culture, a revolution, a “new time and space.”

Beyond the Pale

In the months it is taking me to write this, life intervenes: Ronald Reagan is elected president; the Republicans take the Senate; the Heritage Foundation urges revival of the House Un-American Activities Committee; Strom Thurmond suggests repeal of the Voting Rights Act of 1965; six Klansmen and Nazis are acquitted of the murders of five communists in Greensboro, although the shootings were recorded by four television stations. Things are speeding up; events take on new urgency. But, as I also know, it’s been here all along.

Southern lesbian writing now seems to me to be in a third stage. Some of these writers are staying home, dealing consciously with Southernness from the lesbian-feminist perspective developed outside the South, combining it with an anti-racist analysis that grows out of a close examination of Southern culture. The lesbian-feminist analysis emerged from a decade of multiple liberations. We will apply it in a decade of growing repression. If lesbians in the past two decades sought to create a “new species in a new time and space,” Southern lesbians today take a hard look at the old species, the old time and space. Today I choose to stay South out of a conviction that there is no “better” place to be. This is home; I had better deal with it.

Much of the focus for this self-consciously Southern lesbian literature has come from Feminary: A Feminist Journal for the South. Four years ago, three friends (Susan Ballinger, Minnie Bruce Pratt and Cris South) and I sat down on a screened porch at Yaupon Beach, North Carolina, to clarify our new purpose: “Feminary, one of the oldest surviving feminist publications in the Southeast, announces a shift in focus from a local feminist magazine to a lesbian-feminist journal for the South. ... As Southerners, as lesbians, and as women, we need to explore with others how our lives fit into a region about which we have great ambivalences — to share our anger and our love.”

Feminary had a long feminist history, beginning in 1969 as a newsletter when the energy of the women’s liberation movement hit Chapel Hill. First called Feminist Liberation Newsletter, it bore the marks of influence by the Furies’ newsletter — “The Furies Collective was a religion to us in Chapel Hill between 1971 and 1974,” explains former Feminary member Elizabeth Knowlton. After collective members attended a “Women in Print” conference in Nebraska in 1976, the group decided to turn the newsletter into a journal. Gradually, most members of the original and expanding collective either came out as lesbians or dropped out or moved, until eventually the collective was down to just two full-time members — Susan Ballinger and me (I had joined the year before). It was clear to us that Feminary then suffered from a lack of focus: we were putting out an amorphously “feminist” local journal for we-didn’t-know-who, never saying clearly that we were all lesbians doing the editing. About that time, Nicholson and Desmoines decided to move Sinister Wisdom from Charlotte to Nebraska. They assured us that there was a wealth of lesbian writing waiting to be published. So, taking a collective deep breath, Feminary came out, both as Southern and lesbian. Last year Deborah Giddens also joined the collective.

The first “new” Feminary contained a long article I had written on “Southern Women Writing: Toward a Literature of Wholeness.” In it, I took a hard look at the Southern literary tradition I had grown up in, how it was limited and why, and the influence it had had on me. The heart of my analysis was an explanation of the hold of the grotesque on Southern literature and life, an explanation based on my own lesbian-outsiderness. “Freaks in Southern ‘Gothic’ literature,” I wrote, “reflect a process basic to the small-town Southern life I knew. This community life was confined by the narrow boundaries of what it felt was permitted or ‘speakable.’ The sharply drawn parameters of ‘normalcy’ created its opposite, the grotesque. If some people must be ‘normal,’ then some people must be different from normal, or freak. In reality, everyone is a freak, because no human can cram her-himself into the narrow space which is the state of normalcy. But all have to pretend that they fit, and those closet freaks choose the most vulnerable among them to punish for their own secret alienation, to bear the burden of strangeness.” I went on to explain the necessity to patriarchal politics of the grotesque hold on the imagination: to keep people in their places. At the end of the article, I called for a new Southern feminist literature of wholeness. Since that article, the lesbian part of that new literature has begun to emerge.

In addition to Feminary, Womanwrites, a Southeastern lesbian writers’ conference, has helped bring lesbian writers together to shape a new literature. First held in 1979, Womanwrites will meet this summer for the third time; I am sure that this year, as in the past, the gathering will show an increased power in individual writers as well as in the group as a whole. But thus far, the “we” of Southern lesbians at Womanwrites has been white: no Third-World women attended either year. As Southern lesbians, we all grew up in a segregated culture, and we have not yet found the ways to bridge those chasms — of anger, fear, suspicion, guilt and the great sadness beneath. But it is becoming clear to those white sisters among us that, as we begin to deal with our own racism and the racism of other white people, we will become more trustworthy to our darker sisters, from whatever distance they choose to deal with us. Womanwrites III has in fact set a high priority on meeting racism and anti-Semitism head-on. A statement by the conference’s anti-racist task force announces, in part: “Southern-born or not, we have been raised to hate in many different ways — to hate darkness or Jewishness, and always to hate ourselves as women. Anti-racist work at Womanwrites is an opportunity to us to begin to develop a complex analysis of how these issues appear in our lives and writing, and to begin the work of overcoming these divisions.”

Black lesbians, born Southern or not, continue, like Pat Parker, to express their anger over the racism they en counter among white lesbians. For example, Lorraine Bethel, Georgia-born black lesbian poet, rages in an article titled “WHAT CHOU MEAN WE, WHITE GIRL? OR THE CULLUD LESBIAN FEMINIST DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE (DEDICATED TO THE PROPOSITION THAT ALL WOMEN ARE NOT EQUAL, I.E., IDENTI CALLY OPPRESSED).” She writes: “I bought a sweater at a yard sale from a white-skinned (as opposed to Anglo- Saxon) woman. When wearing it I am struck by the smell — it reeks of a soft, privileged life without stress, sweat or struggle. When wearing it I often think to myself: this sweater smells of a comfort, a way of being in the world I have never known in my life, and never will. It’s the same feeling I experience walking through Bonwit Teller’s and seeing white-skinned women buying trinkets that cost enough to support the elderly Black woman elevator operator, who stands on her feet all day taking them up and down, for the rest of her life. It is moments/infinities of conscious pain like these that make me want to cry/kill/ roll my eyes suck my teeth hand on my hip scream at so-called radical white lesbian-feminist ‘WHAT CHOU MEAN WE, WHITE GIRL?”’

Or as Lou, a black lesbian-feminist separatist in South Carolina, writes:

once i tried to

identify

with everyone else

trying to beat me down

no thanks

The divisions created by centuries of racism and class inequity are at least as deep as those arising from centuries of homophobia. For the lesbian today, writing must be rage, writing must be clarity, writing must be challenge and healing.

We must claim our sadness and our separations. Black lesbian Ann Allen Shockley’s writing goes far toward doing that. Shockley is a librarian at Fisk University; she has devoted much of her life to black scholarship and is the author of Black American Authors and A Handbook of Black Librarianship. Only in the past four years has she published lesbian fiction: Loving Her, a novel about an interracial lesbian relationship, and The Black and White of It, the first collection of short stories about lesbians by an Afro-American writer. One of Shockley’s characters, a 40-year-old white lesbian college teacher, looks out a window: “Loneliness flooded her like the bone-chilling spectre of the damned.” The Black and White of It explores the loneliness that comes from our various separations: black from white, straight from homosexual, old from young, old dyke from new lesbian. Shockley has lived in the South most of her life. She writes more out of sorrow than of anger, from the pain of separation and the wish for a different wholeness.

Much lesbian writing over the past decade has been a search for transformation, for the healing of these separations. When a woman comes out as a lesbian, she has a tremendous sense of the power of personal change, of the breaking into new worlds, uncharted terrain. As black lesbian writer Doris Davenport (born in Georgia but living in Los Angeles) explains:

every day i repeatedly

give birth to me.

sometimes prematurely

sometimes stillborn

sometimes in the morning

or later on.

not just once a day.

sometimes as many as ten.

after a while, i'm having

reincarnations

less messy, but they feel the same.

one day i had me

300 times, each time different

except the last when i

became what i was at first

to provide some continuity

and point of reference.

Susan Wood-Thompson, Texas-born lesbian poet, describes one such transformation in her long, moving autobiographical poem, “Trying to See Myself Without a Mirror.” For Susan, it was a search for herself, for sanity and for other women that led into the locked ward of a mental hospital and attempts at suicide and out again to bring back the knowledge:

The bond of suffering

is that we know

we begin with what we have

and do not measure each other

against a perfect husk

that never burst with pain.

Minnie Bruce Pratt, in another long and beautiful poem, “The Segregated Heart,” traces her own transformation from her Alabama girlhood through marriage to divorce and the loss of her children because of her lesbianism: “to leave where I could not stay, to bend myself to change was to leave where I also loved.” Lesbian poems, like lesbian lives, are best when they operate on the mysterious edge where life continually dies and is born.

It is against the background of the natural world — of shifting afternoons and days and seasons and years — that the lesbian writer searches for transformation. This is especially true of the Southern lesbian writer, whose writing is also influenced by Southern landscape. Natural images in her poetry reflect the perception that “patriarchy” is based on abstract thinking and living that kills, because it fears fluidity, change, emotions, nature, life, the female. As Susan Griffin’s book Women and Nature demonstrates, the male impulse to conquer and tame nature and to conquer and tame the female are the same. The lesbian also identifies nature with the female, but it is — or can be — with the reverence that a woman can feel for another woman’s body. Melissa Cannon, Tennessee lesbian poet, writes in “Grand Tour”:

Your eyes lose themselves

among rich curves, vivid petals –

arc of apricot,

blush of plush

coral of shell lips,

the blood wave’s crimson

You come at last to a small cave

mountain shadowed.

It is guarded by a priestess

hiding under a velvet hood.

Do not lower your eyes.

The short stories of Diana Rivers, a lesbian born in New York but living on a women’s land trust in Arkansas, show the power that comes when women speak as the land. For much of English literature, the male hierarchy that put man over woman also put spirit over nature and reason over feeling. It is nothing less than revolution to reverse that order. Faulkner’s stories are full of little old ladies trapped and crazy inside dusty houses, while the men are out conquering The Land.

In Diana Rivers’ stories, women have taken back the wilderness. Women are the wilderness. In “Hawk,” the last of her Sister Stories, an old woman looks back over her 40 years in Arkansas:

When we first came here we were all so different. Mira had five children. Omi had never been with a man. Some of us grew up poor and some rich, some came from the country and some from the city. There were those who cried because it felt good and those who never cried at all. We thought we’d love each other because we were all women - but oh what fights we had. We struggled over everything. Political struggles, personal struggles, sometimes both together, shouting and crying. . . . So much anger. At one time it got so bad I left. I was sure I’d never come back. We’ve grown more tolerant or lazier. We don’t feel so responsible for each other’s virtues.”

If knowledge of the natural world helps transform lesbian lives, the lesbian’s own shift in consciousness also transforms the Southern landscape. Minnie Bruce Pratt has told me how reading Senate reports on Klan activities in Alabama in the late 1800s near her home town has given her a horrifyingly different view of the familiar terrain of childhood. Cris South is at work on a novel about a lesbian who lives in the country — Klan country — doing anti-Klan work. Catherine Risingflame Moirai’s poem “Taking Back My Night” traces her own shifting view of the landscape of night and day, from her early fear of “the dark” — which she comes to realize includes the “dark races” and herself as lesbian and woman — to a terror of male “enlightenment”:

Tonight I will walk in darkness

feeling my way home

by the curve of the earth

feeling my way to sleep

by the curve of a woman.

If I wake in the night

she will soothe me.

If the men in white come

she will not desert me. . . .

I am still learning to walk

where I am afraid.

With such a change in consciousness, the Southern lesbian writer does begin to move “beyond the pale.” In Pratt’s “Death Row” the voices of the dead speak to us from the fields:

Child, what have you been up to while we

were trying to keep body and soul together?

But never mind that now. Here’s what you must do:

Tie a red flannel string around your waist

for strength. Plant your roots

at the dark of the moon. Remember your past,

and ours. Always remember who you are.

Don’t let the men fool you about the ways of life

even if blood must sign your name.

In the past four years, a strong Southern lesbian-feminist literature has begun to emerge. Those of us writing it have moved from a powerful sense of our transformations as they fit into natural rhythms, to seeing the world in a different way. What’s next? I wish I knew. I think the next step for Southern lesbian writing will be to explore the connections between seeing the world differently and making the world different.

We cannot disconnect our lives from what will happen in American society in the coming decade. Over the past 20 years, American society has developed clear models for personal and social transformation. First the revolutionary energy of black people in America again erupted, as a generation of black people threw off white definitions to see themselves as beautiful and to move in that power; with the gift of their example, women and homosexuals did the same. All along there were those who feared the power of these transformations: the knowledge that when some change, all must change. These forces today fight to keep the world static. But we will not go back.

Tags

Mab Segrest

Mab Segrest is a writer, teacher, and organizer who lives in Durham, NC. She has written two books, My Mama's Dead Squirrel and Memoir of a Race Traitor. She is working on a third, Born to Belonging. This is excerpted from an essay that appeared originally in Neither Separate Nor Equal: Race, Class and Gender in the South, edited by Barbara Smith (Philadelphia: Temple, 1999). (1999)