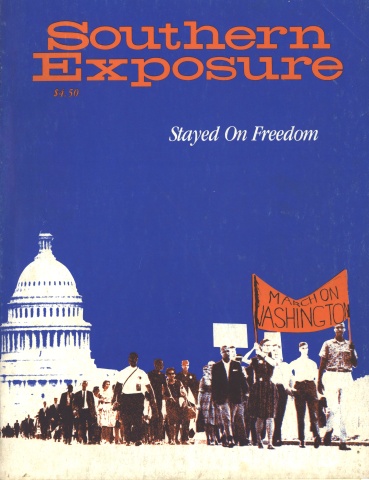

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

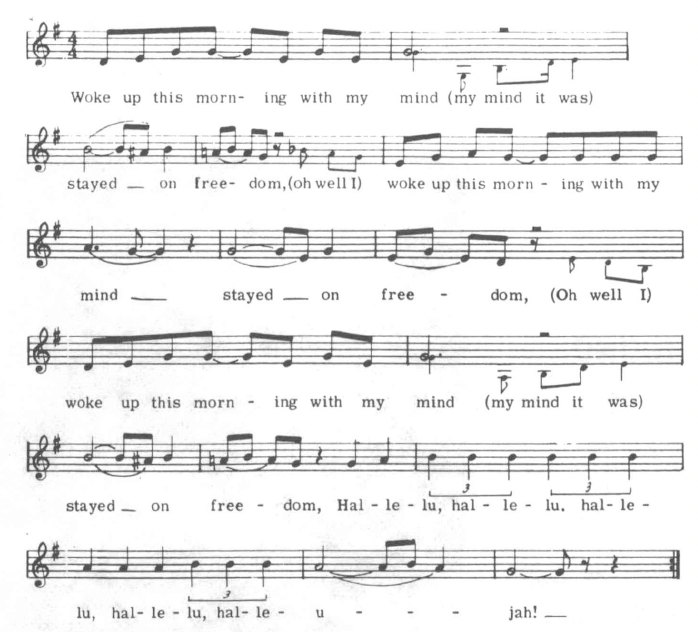

Ain’t no harm to keep your mind stayed on freedom,

Ain’t no harm to keep your mind stayed on freedom,

Ain’t no harm to keep your mind stayed on freedom,

Hallelu, Hallelu, hallelu, hallelu, hallelujah!

Walkin and talkin with my mind stayed on freedom…

Singin and prayin with my mind stayed on freedom…

The freedom struggles sparked by the Montgomery Bus Boycott have touched and influenced more Americans than any other event in this century. “Stayed on Freedom” shares the stories of what happens when you get involved in the Movement: you wake up in the morning with your mind on freedom, you walk and talk with your mind on freedom, your whole life is dedicated to building a new order based on joy and fellowship, free of racism and exploitation.

Since the first Africans arrived in America in chains, the liberation movement has always been composed of people whose minds are stayed on freedom. At its core, the force of the Freedom Movement of the 1950s and ’60s emerged from people, huge numbers of people marching with humility and pride along the same path, united by a common vision of humanity, justice and people’s power. Music was the language of the Movement, the preacher its mouthpiece, students and mothers its shocktroops, the Bible and Constitution its foundation, the kinship of all people its power and authority. In a naive yet profound belief in the capacity of Americans to rise above their historical handicaps, the Freedom Movement made visible the raw division between black and white societies, and with compelling force, it made the country choose between snarling dogs and singing marchers.

Today, the gains of the most recent phase of our Movement - the last 25 years — are in jeopardy. Part of the problem comes from our failure to preserve the political and moral force of the Movement’s unity while expanding our vision to include struggles for full employment, nationalized health protection, public ownership of primary areas of the economy (including energy and housing) and other structural changes in our political economy. Part of the problem results because those who would subvert social justice — including old adversaries like Strom Thurmond and Ronald Reagan — have seized the initiative and now plan an aggressive attack on everything from the Voting Rights Act to the Food Stamp program.

We are now called upon today to defend freedom and confront savagery in whatever new forms it takes; we must not take one step backwards, but must build on the strengths and insights of the Freedom Movement with a more tough-minded analysis and more far-reaching goals. Toward that end, this book offers profiles of struggle, self-criticism and guideposts for our future work. We’ve aimed it especially at the many would-be freedom fighters who are looking for symbols of courage and who are anxious to learn from those who battled against the police-state conditions that existed in the South in the 1950s. Reading these pages, we hope that our youth will become inspired and will walk in the shoes of Lucretia Collins, E.D. Nixon, Gwen Patton, James Orange, Anne Braden, Ella Baker, Rosa Parks, John Lewis, Bob Zellner, Charlie Cobb and the thousands whose Movement experiences remain unrecorded here or anywhere. Having their stories told is particularly important now that perceptions of our Freedom Movement are distorted by the entertainment-oriented media, which limits our history to a string of dramatic court decisions or bold actions by a single leader.

“Stayed on Freedom,” like all products of the Movement, does not result from the effort of a small group of people working in an isolated office. We have been guided throughout by the pioneering work of Freedomways, a journal that celebrates its twentieth anniversary in 1981, and we pay special tribute to its editor, Esther Jackson, who has deep roots in our Southern struggle. We have also drawn from the tradition of music in the Movement. Not only does a song give us our title, but it also inspires us daily. We give thanks to Guy Carawan and Candie Carawan, true brother and sister of our Movement, for their book of songs, We Shall Overcome, from which we have taken the music in this book.

One caution: these personal stories, photos and songs are obviously not a complete history of our Movement, much less of the past 25 years. We have been forced to include only a few of the countless theatres of the Movement — in the South, in the nation, in the world. In addition, we have passed over the struggle to desegregate the nation’s schools, which was the focus of an earlier issue of Southern Exposure, “Just Schools.” We see “Stayed on Freedom” as but one in a series of Southern Exposures which put the Movement at center stage. We intend to cover both the past and present activities of the Movement in future issues, and encourage you to send us your favorite Movement photographs, those diaries and letters collecting dust, the poems and essays that bring a special meaning when you submerge yourself in Movement activism.

Lastly, thanks for subscribing, purchasing or borrowing “Stayed on Freedom.” We at Southern Exposure hope that this book will open up a significant period in this country’s history — the most significant for those of us who came of age during it — and will strengthen each reader in making his or her contribution to the Movement today.

Tags

Pat Bryant

Pat Bryant is a writer, community organizer, and director of Gulf Coast Tenant Organization, which operates in poor African American communities in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. He is a board member of SOC and the Institute for Southern Studies in Durham, NC.

Pat Bryant is an editor of Southern Exposure and field organizer for the Southeast Project on Human Needs and Peace. (1982)