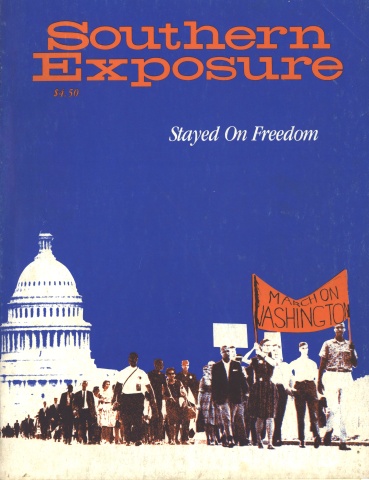

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

February 1, 1960, marks the date of the historic Greensboro sit-in by David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeill and Ezell Blair, students at all-black North Carolina A&T University. Their action sparked student protests at lunch counters around the South and in some Northern cities. (See “The Greensboro Sit-Ins, ” Southern Exposure, Vol. VI, No. 3, an excerpt from William Chafe’s history of race relations in the city entitled Civilities and Civil Rights.)

The segregated lunch counters were not eliminated by the first wave of sit-ins in Greensboro. City officials called for a cooling-off period, but when Woolworth’s and other segregated eating facilities refused to negotiate seriously, a second wave of protests began in 1962.

The following interviews — conducted by the Greensboro Public Library’s Oral History Project, headed by Eugene Pfaff Jr. - offer insight into the organizing and protest activities within the Afro-American communities. Although Jesse Jackson is the most prominent personality to emerge from the Greensboro demonstrations, Pfaff focuses on others who contributed to the situation behind the scenes. William A. Thomas, Jr., was a student at all-black Dudley High School at the time of the 1960 sit-ins. At first the young high school student was on the fringes of the sit-ins, but when A&T recessed for the summer, his leadership was needed.

Dr. Elizabeth “Lizzie” Laizner began teaching at Bennett College, a black women’s college in Greensboro, the semester following the initial sit-ins. In 1962, she got involved as transportation coordinator for Bennett students, and was one of the few whites in the city to join the Congress ofRacial Equality. She is currently a professor of humanities at Shaw University, a predominantly black university located in Raleigh.

Clarence C. “Buddy”Malone, Jr., began his law practice a few months after the 1962 wave of sit-ins. Affiliated with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Malone had defended several persons who were victims of civil-rights violations. At that time, he was one of the few Movement lawyers in North Carolina, and traveled from his native Durham County to nearby counties representing black and indigent defendants.

During the Greensboro sit-ins, Malone was retained by CORE, receiving only his expenses as compensation, as was the case with most civil-rights attorneys in the mass demonstrations in the South. Along with the national CORE, he set the trial strategy.

Dr. Willa B. Player was president of Bennett College, a private black institution, during the sit-ins. Her supportive role during the demonstrations stood in sharp contrast to that of President Lewis Dowdy at North Carolina A&T, which was dependent on the state for most of its funds.

THOMAS

I first became involved my senior year in high school. I was a student at Dudley. That was during the summer of 1960, right after the sit-ins first started. Initially, the students at A&T felt that the high school students were too young to actually be involved in the sit-ins, but they found that the situation was not going to be resolved by the time school was out, and that many of the students that initially participated in these demonstrations were from out of town. They weren’t there to carry on, so that’s when the high school students initially got involved.

At that time, the NAACP’s basic tactic was through the courts, through legal action. We felt as a result of the sit-ins that more was needed. I was president of the youth chapter of NAACP in Greensboro at the time. Through Dr. George Simkins, then president of the adult branch, we contacted James Farmer, national director of CORE, inquiring about the possibility of forming a CORE chapter in Greensboro. Through those efforts, a CORE chapter was in fact initiated in 1960, and I became its chairman. Our activities consisted basically of picketing the dime stores, leafletting, negotiating with the mayor.

What really triggered the massive demonstrations was an inability on the part of the political and business structure to take the damn thing seriously. Because we didn’t have the violent outbreaks and disturbances that characterized demonstrations that existed in other parts of the country, they thought that the thing would just go away. They attempted to ignore us. In fact, at one point, the mayor did not even want to negotiate with the students. He suggested that we send some “reasonable, mature” adults down to negotiate with them. We quickly informed him and the other committee members that it was not the mature adults that were out in the street and that if he wanted to get us out of the street, he would sit down and talk to us, which he eventually did, and that’s when the problems were worked out.

Once students knew what was going on, it had a snowballing effect. We utilized the media, we utilized leaflets. The local churches were very cooperative in letting us use their churches for mass meetings. You had to have some central place where instructions could be given as to exactly what tactic would be used that particular evening, exactly what strategies we would be using, where we were going, etc. The mass meeting afterwards was emotional, religious and also strategic. It afforded us the opportunity to assess what we had done and to make plans for the next day. Each day’s activities were in fact planned with some degree of flexibility to be able to adjust to the situation once we arrived at our target area. It did not just happen; there were factors to be considered and analyzed before it was decided exactly what would occur: you may have felt that a silent demonstration may have been more effective than the singing of a more vocal demonstration. CORE taught us how to respond to different situations, and other communities were able to look at us and learn from the experiences we had in Greensboro.

Things, in terms of action, went pretty much according to plan. The basic form of action was through economic withdrawal, another name for boycotting, and through street demonstrations. Very little litigation went on at that time, other than defending those people who were arrested.

After they started to arrest people, we literally adopted the slogan that we were going to fill up the jails. Again, that was an economic thing. It cost the city of Greensboro and the state of North Carolina a considerable amount of money to house these people, to feed them and to guard them, for no reason. The jails were literally filled. They were overflowing.

I was only incarcerated twice. I guess the reason that I was not arrested any more was that the committee that I was working on felt that I would serve more of a purpose if I was on the outside. In fact, at times I probably would have welcomed arrest. I could have gotten some rest. That way, you didn’t have to be up meeting around the clock and organizing other activities 24 hours a day.

When the Greensboro Chamber of Commerce and the Greensboro Merchants Association passed resolutions advocating desegregation of all public facilities, our reaction was that we always welcomed any support we could get, but those committees had no enforcement. Resolutions are all well and good, but they could not command anyone to do anything. The point that they were trying to make with the resolution was, “Okay, we have made a resolution, so call off your dogs.” We were not going to stop demonstrating until they actually desegregated. The resolutions didn’t mean a damn thing. They showed some good faith, but the places were still segregated.

The arrest of A&T student body president Jesse Jackson on the felony charge of inciting to riot played right into our hands because but for that, quite possibly, the demonstrations could have fizzled down. At that particular time, the demonstrations were beginning to be the same old thing; the emotional level had reached its low ebb and we needed a lift.

There was no riot, that was a joke. The only thing that happened was that Jesse led the group in prayer, and Captain Jackson got on his bullhorn and told us to disperse, and Jesse said “Not until we have our prayer.” And he told everybody to kneel, and they did kneel, and he prayed. He prayed for the captain and everybody else, and afterwards they rose and they got back in line, two by two, and we marched back to the church.

An interesting thing about that is that I was right next to Jesse and it was myself that asked Jesse to lead us in prayer after Captain Jackson had requested or ordered us to move. Well, the difference was that I was a Greensboro boy; they considered Jesse an outsider. That’s why he was arrested and not myself. They wanted to punish the outsider. I think that they felt that Jesse was conspicuous, that by eliminating him, by locking him up, then that would cause the demonstration to fizzle.

LAIZNER

I did not join CORE at first for a very strange reason: I thought at that time that this was really a black affair and that a white person might not even be wanted. I suddenly got into it when I was sitting at a friend’s house and the TV was on and they showed one of those slightly strange — I would call them “professional” — civil-rights workers from the North who came to help with picketing and had, somehow, managed to get himself arrested and get some publicity for himself and for the group, which was, of course, his purpose. And I remember just about blowing a gasket, saying, “Why hadn’t anybody told me that whites can be in on this?”

In the fall of ’62 our main targets were the S&W and the Mayfair [cafeterias], but when we didn’t get anywhere, the boycott was initiated in the then very busy downtown just before Christmas. It was beginning to hurt, and this is when the city nominated a human relations committee. Mayor Schenck did it. We did not realize at the time that the committee had very little power. What the committee, to my knowledge, was really supposed to look into was the justification for opening these places. Were they really being unjust to the black citizens of the town by not permitting them to come in?

We were officially approached by either the committee or the mayor to call off the boycott and preferably cease picketing and give the committee a chance. I still remember the session we had in open meeting; it was very heated. I was on the side of the group that we called the “activists,” the ones who said, “Nothing’s going to come out of the committee; we’d better go on.” Bill Thomas, Pat Patterson and Lewis Brandon were some of the moderates. The majority decided that we should give the committee a chance and cease demonstrations until up to sometime in February, 1963, whenever they would come through.

In a very moving declaration signed by the head of the committee, who was either one of the big textile people or one of the big bankers, the committee brought out the injustice that segregation was doing to the black citizens of Greensboro and they felt that definitely those places should be opened. It sounded gorgeous. That declaration was printed all over and much praised, but it wasn’t worth the paper it was printed on. The trouble was in the last line: “Unfortunately, our committee has no power to enforce these suggestions.” That was it. That’s when we restarted and the first tiling we did was to picket the city hall.

By early May we had picketed city hall and had done a little picketing of restaurants, but it didn’t go very far because people were tired, and there was this question: should we or shouldn’t we go on and do something right now with exams staring students in the face? Should we prepare something big for the fall? That is when Bill Thomas had a call meeting at one of the Bennett dorms.

Bill, leaning against the piano, put it to the others and gave two possibilities: “Let’s either do something little or let’s not do anything. Let those of us who will be in Greensboro in the summer prepare a big thing for the fall.” We almost had the feeling that Bill leaned toward that, which sounded good and would have been good. At that time, some of us spoke up for the idea that something had to be done, we had to make people aware of segregation. A small group was nominated to get together and work out something for a small picketing job. And that small picketing job that we worked out, and which was approved, was McDonald’s.

Several of us had gone over to High Point in support of their people picketing. They had halfway opened the McDonald’s over there, which gave us the idea. Also, there had been an incident at McDonald’s in Greensboro much earlier that created more stir and more sympathy for our cause than anything else. It was a letter by a non-Greensboroite in the Daily News. That person had been in the drive-in line at McDonalds and next to him was a black family, also in a car, and they all waited. Obviously the black man was from the North and didn’t know what the case was then. He was sent back and could not be served. The white man was very, very furious and upset about it, and he wrote a very moving letter about it, on the injustice of it. And several people came in with strong letters in support of that. So we decided in May that the McDonald’s out at Summit Avenue would be a good place to go.

We waited for an opportune moment when the place was pretty empty and went in in a long row. The man informed us that we had no right to be served and that we would be arrested. This is when Reverend Busch, Bill Thomas, Pat Patterson and Reverend Stanley had themselves deliberately arrested. And that was what created the stir: two ministers and the leaders of the group had been arrested.

Floyd McKissick [of CORE] immediately came down and visited them in jail. The publicity was magnificent. This is when McKissick really did the right thing. He said to the four, “Take that bail. Get out, because now we can start something. This is going to start it.” And he was 100 percent right. As soon as Bill and Pat were out, we called a meeting over at the Hayes- Taylor YMCA.

We invited the ministers, anyone who wanted to come. What we needed was to see if we could get the support of the grown-ups. If the ministers would tell the black community that this was a worthy cause, to go and support it, they would. Reverend Bishop came. He was the president of the Minister’s Association, the black one, and he said they would listen to whatever he had to say.

Reverend Bishop was sitting there, and he said, “You’re right, we will support you.” And then he said, “I realize that you have finals coming and everything. Just do something little. Picket here or there so that I can tell the people that something is going on and that you need support.”

And those of us who were there decided that if he wanted us to do something, why didn’t we go back to McDonald’s that very evening. And I remember going home and organizing the car pool. We wanted to have them spelled every hour because picketing was strenuous and it would be better for them at night. The first group was set for six or seven, then one at eight, and I came on with the last group at nine.

This was when the mess occurred, because the place had closed earlier and some — excuse me for using a nasty word — “nigger-baiting crackers” were down there in force and there wasn’t a friendly soul among them. The parking lot of McDonald’s and the service station next door were filled with between 300 and 400 jeering crackers of the nastiest kind. For them it was sort of a Sunday entertainment; for free they could stand and jeer at us. The crowd was getting unrulier and unrulier. We knew that it could get nasty as it grew later, so a little after 10:00, Bill made the decision to break up. He informed the police that we would go fast to our cars and get out.

We decided to do something again the next day. This is when it really got big. The A&T students must have told others; they just simply kept coming. We had practically 2,000 that evening. McDonald’s was completely filled with people, and the manager went up to Bill Thomas and said, “I am closed, but you are still trespassing. If you do not leave, we can have you arrested.” This is where Bill made the very, very smart move of saying, “No, we have done what we wanted to do. The place is closed for the night and I guess we will go back.”

One of the young ladies then said, “Let’s go downtown, and maybe go by the Carolina Theater.” We made a totally spontaneous decision. We all went downtown, the whole spate of us, and there was that tremendously moving scene where we knelt down on the sidewalk. I don’t remember which hymn we did. It was not our usual “We Shall Not Be Moved,” it was a more religious one that someone suddenly started humming. A young man who later became an Army chaplain was the only one standing, and he prayed for the people in the Carolina Theater. It was so reminiscent of what one year later Martin Luther King said, that we should all be as brothers, that God should enlighten the people who are sitting in there and that we should all be together as brothers.

McDonald’s capitulated four days later. We were on our way home from picketing downtown on Tuesday when we were told, “Don’t disband. Go to the Y. There’s something going on there.” The manager of McDonald’s was there. What he said then was very contrary to what he had said on that Sunday. He thanked us, and Captain Jackson thanked us for our restraint. And the manager apologized to the four gentlemen whom he had arrested.

On Wednesday, at a mass meeting at the Y, we decided we were now going for an arrest. We had seen what an arrest of just four people had done for McDonald’s; now let’s see what this is going to do for the others. Some of us had had some courses in nonviolence with Floyd McKissick and some reps that came in from CORE. So we planned to jam the revolving door at S&W, and jam it successively. We tied the place up completely in this way. The whole mass of students were out there picketing where nothing could happen. And they knew exactly who’d be in the first group, who’d be in the second group, who’d be in the third group. As soon as we were told that we were under arrest, we would go out and the next group would jam the door again and be arrested.

I was in the first group. I didn’t, shall we say, follow the other 800, if you see what I mean. I was mainly the white auslagershield, the window dressing. Unfortunately, you got better publicity if you were white. I would seem much more important to people than I actually was, by the fact that I had to regularly be toted out and put in the first row.

The first time we were arrested, we were let go again. But people were getting pretty upset, so we decided on Friday this time they were going to keep us, and they did. Our record of 1,850 arrested in one week still stands. And do you know who came in? [Willa] Player [president of Bennett College]. When we were in jail, there was a support committee nominated by Bill that could act for CORE, and Player headed that committee.

They wanted us out because it was creating a nationwide stir, it was bad for the reputation of the city, it was horrible for the finances of the city. Mayor Schenck went on vacation in Virginia, and that elderly gentleman who then became mayor [William Trotter, Mayor Pro Tern] took over. It was he who gave in to that group with Bill and Dr. Player and others, who gave them their first condition: a human relations committee headed by a black doctor, Dr. Evans.

I had heard mutterings from those who had come out of jail that they wanted to go back. The heroes that came out of jail felt that they hadn’t, with their very real sacrifices, gotten enough. It could have split the group. The majority would certainly have decided on something more peaceful, but we would have antagonized our most valuable people. This is when I did something I normally did not do: I addressed the group.

I remember saying, “I know what we all want to do, and what I would like to do, too, would be to go right back. But this is not what we should do. We’ve got to give Dr. Evans a chance.” So the march started. That was the march of 5,000.

Mr. Farmer suggested a silent march. He is a fantastic speaker. He said that it would impress them if we went there, not speaking. We marched straight through the square and then back again. We made a circle of the town. There were only three in the first row: Jackson, me and Farmer.

We had the Evans Committee. We were sure that the grown-ups would take over after students left school for the summer, and they did. The S&W was open, the movie houses were open, some other little restaurants were open. In fact, we were one of the few towns in the South that were open before the ’64 Civil Rights Bill demanded it.

PLAYER

I first learned of the Woolworth’s sit-ins [in 1960] when we were all called downtown and heard the A&T student present his case. We, as members of the community, were trying to get a hold of what was really happening.

Ezell Blair was asked to defend his actions, which he did admirably. Here were students who were realizing that as citizens and as students at a liberal arts college they were being denied their equal rights, both under the law and under their constitutional beliefs, and freedom of expression. I defended them. I called the Bennett faculty into a meeting and told them what was happening. We went back to the purpose of a liberal arts college, and in defining those and what the girls were doing, we decided that they were carrying on the tenets of what a liberal education was all about — freedom of expression, living up to your ideals, building a quality of life in the community that was acceptable to all, respect for human dignity and personality. It was a recognition of values that applied to all persons as equals, and all persons who deserved a chance in a democratic society to express their beliefs.

We spoke to the president of the Student Senate, and we told her how the faculty felt, and that we were planning to cooperate with the girls. The only thing we requested of them was that they should give us a daily report of what they intended to do for that particular day.

By the fall of 1962, almost the entire student body at Bennett had become active in daily picketing. Governor Sanford tried to get the students to cease the demonstrations. We had a meeting at the governor’s mansion in Raleigh [one of a number of meetings] designed to try to get us to pull out and stop our students from demonstrating. Then there was a meeting just with me and the CORE director and one of the Greensboro citizens, Warren Ashby, over on the Bennett campus. I distinctly remember Dr. Ashby with Dr. Farmer ask me if I would be willing to pull in the Bennett College students because the A&T students were being pulled in. The governor had written a letter to President Dowdy telling him that he should have his students stop the demonstrations. Of course, I refused to do this.

Dr. Dowdy was under tremendous pressure. A&T was a public institution, and the difference between a public institution and a private institution was that a private institution could not be dictated to by the state.

I never equivocated on it at all; it was so clear to me that what these people were struggling for was within their rights. Because of that, the students were very cooperative. They would always come to me first to tell me what they were going to do or what they were planning, or what it was all about, and they would ask me if I had any suggestions. So it was a communication and a give-and-take that was so open that the students never did anything behind your back.

MALONE

From time to time, I was consulted on the legality of the decisions that were obviously made almost hour-to-hour. But for the most part, they relied on the general consensus of the CORE chapter and the national office of CORE.

It was my contention and that of CORE that the trespass law as it was being applied was unconstitutional, and for that reason we were testing the legality of it. I advised my clients that we had a moral duty to assert those rights guaranteed to us by the Constitution. In fact, the action of the state and city in enforcing the segregation laws was both morally and legally wrong.

Ordinarily, the merchant himself or the individual business owner exercised self-help; he’d clobber the guy across the head and toss him out. It was only with the beginning of mass sit-ins that it reached large enough proportions that it was necessary to call in a large amount of state action to enforce segregation.

The individual, in his private capacity as a citizen, had a right to refuse service if he so chose. However, state action in enforcing this whim was invalid under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. That was an abuse of police power to lend aid and enforce his private whim against the rights of other citizens.

It was simply a matter of developing trial strategy based upon the factual circumstances. In a war like that you utilize anything you can come up with that is tactically effective. One of the strongest things we had going for us was the inability of people to identify the students; we simply capitalized on the age-old adage that all blacks look alike to whites. A tremendously large number of those arrested for blocking fire exits and trespassing were dismissed for lack of evidence.

The major number of persons arrested arose out of one march. They were charged under a construction ordinance, really, for blocking a public street. What happened was that they marched down to Elm and Market Streets, the hub of the traffic center, and laid down in the middle of the street and blocked traffic in every direction. There must have been 1,500 or 2,000 persons arrested at that time and charged with blocking a public street. Those cases were subsequently carried to the State Supreme Court, which threw out the application of the ordinance because it was taken out of context and therefore simply did not apply.

The feeling was extreme throughout on both sides. It was a feeling of crisis, the “we”s and the “they”s. Both sides exercised all of the psychological tactics that they could. For instance, I sat in on what were ostensibly official city negotiations. In an effort to call off the demonstrations, commitments were made that, before you could get in your car and turn on the radio, were being denied by officialdom, by the officials that had just made the commitment behind closed doors.

There was an absolute distrust for Mayor Schenck. It was proven time after time that anything that was said by him was what he thought was appropriate at the time with no thought of ever — in any way — adhering to any promises or discussions that he made.

The demonstrations had been going on for three or four days, possibly more, when the first case came to trial. There was some element that made the warrant improper, and I moved to quash that and reasonably argued the basis of my motion. And the court allowed my motion to quash.

Now, as a matter of plain old logistics, the warrants had been mimeographed. Upon the allowance of my motion to quash the first warrant, I called to the court’s attention that all of the warrants were drawn exactly alike, and for that reason, I moved to quash them all. And of course, the district attorney then moved to amend the warrants to properly allege a crime, at which juncture I simply insisted that each of the defendants be served with new copies of the warrant because every defendant to be tried in a criminal action has a right to know of the offense whereof he is charged before coming into court. Now, this was a major bogdown tactic for the simple reason that, as many people as were in the various centers of incarceration, there were absolutely no ascertainable records of where or who anybody was.

The true spirit behind the Movement was Bill Thomas, who was reasonably unidentifiable; he was quiet of manner and really nobody in the city administration knew where the impetus or the guidance was coming from. Since it mostly consisted of students, the Movement focused on A&T’s campus. Well, Jesse Jackson at the time was president of the student body at A&T. He was the least effective of the student leaders at the time, but he represented to the power structure a leader because of his position as president of the student body. He made a couple of fiery speeches and so on. And he, being the titular head of the student body, was charged with the more serious felony of inciting to riot simply as a tactic of picking off the top — you cut off the head and the body is bound to die.

There was no riot, but there was a chance of conviction. The climate and tenor of the times were such, and of course the jury selection process was as bad as it is today. The jury selection process at the time was geared so that the sheriff or the officialdom could rig juries any way that they wanted them. Jackson’s case was finally dismissed in the spirit of cooling things down.

After the momentum of the mass jail-ins and that kind of thing had stopped and negotiations had begun, there was no reason for continuing demonstrations; but while the demonstrations stopped, the litigation went on. We slugged it out for a good many weeks in the Recorder’s Court, until I think everybody’s tongue was dragging. So I finally requested jury trials in all of the cases so that we could get up to the Superior Court. The trials of the persons arrested during the height of the demonstrations went on up into the early fall, which culminated in the Supreme Court opinion in the State against Fox case, which sort of laid to rest all of the remainder of the cases.

Legally, desegregation was never accomplished through the courts. The final and ultimate blow to desegregation was dealt by the passage of the Civil Rights Bill of 1964. Bit by bit, piece by piece, we hacked away at it in the courts, and obviously the climate of the times led to the passage of the legislation. But I don’t think that the climate would have been such that the legislation would have been passed in Congress had there not been the general upheavals that were really the manifestations of the seething feelings among blacks against segregation.