The First Freedom Ride: 1947

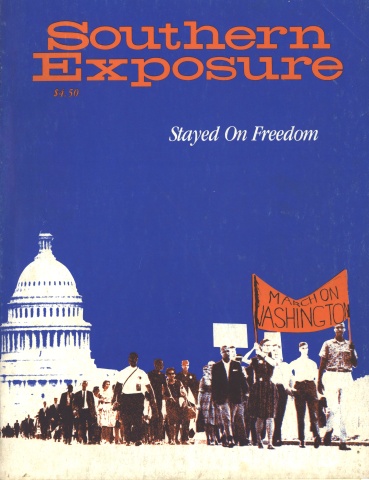

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Jim Peck is a former staffer for CORE, and now works for Amnesty International. He is currently active in demonstrations against draft registration. Following the recent testimony of Gary Rowe, Jr., undercover agent for the FBI in the Klan (and one of the men accused of assaulting Peck in Birmingham in 1961), Peck filed a $500,000 lawsuit against the FBI. The suit is based on Rowe’s testimony that the FBI and police chief “Bull” Connor agreed that the police would be absent for 15 minutes after the arrival of the Freedom Riders to leave Klansmen time to clobber the demonstrators. During the melee in which Rowe took part, Jim Peck and Walter Bergman were severely beaten. This account is excerpted from Peck’s 1962 book, Freedom Ride, published by Simon & Schuster.

“Was the Freedom Ride worth it? Would you do it again?”

These questions were tossed to me in 1961 as I lay on an operating table in Hillman Clinic, Birmingham, Alabama, waiting for the doctor to finish sewing 53 stitches in my face and head. To their surprise, I explained that this was not my first Freedom Ride, that I had been on a previous one in 1947.

The 1947 trip was not called “Freedom Ride,” a term coined by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) for the 1961 bus trips. It was called the Journey of Reconciliation, cosponsored by the Fellowship of Reconciliation and CORE. It took place just a year after the first Supreme Court decision to outlaw segregation in interstate travel, the Irene Morgan case.

It was a particularly quiet, gray Sunday afternoon in Chapel Hill, and white cab drivers were hanging around the bus station with nothing to do. Then they saw our Trailways bus delayed and learned the reason why. Here was something over which they could work out their frustration and boredom. Two ringleaders started haranguing the other drivers. About 10 of them started milling around the parked bus.

When I got off to put up bail for two Negroes and two whites in our group who had been arrested, five of the drivers surrounded me.

“Coming down here to stir up the niggers,” snarled a big one with steel-cold gray eyes. With that he slugged me on the side of the head. I stepped back, looked at him and asked, “What’s the matter?” He gave me a perplexed look and started to walk away awkwardly. My failure to retaliate with violence had taken him by surprise. I have found that use of nonviolence in such situations often has this effect. As the driver walked away a passenger who was standing outside the bus shouted at him, “What’s wrong with you? That man didn’t do anything to you.”

I later learned that the sentiment among passengers waiting aboard the bus was predominantly in our favor. A woman from Winston-Salem, North Carolina, spoke up for us in a discussion of the incident among the passengers — and even gave one of our observers her name and address in case we should want her to testify in court. Another white passenger got off the bus, went into the station, and protested to the driver against his ordering the arrests.

When the four who were arrested were bailed out and left the courthouse in Reverend Charles Jones’ car, 12 of the drivers piled into three cabs and sped after us. We succeeded in getting to Reverend Jones’ home before them. When we got inside and looked out of the window, we saw two of the drivers getting out with big sticks. Others started to pick up rocks by the roadside. Then two of the drivers, apparently scared, motioned to the others to stop.

They drove away. But a few minutes later Reverend Jones, who since the CIO meeting in his church had been marked as a “nigger lover,” received an anonymous phone call. “Get the niggers out of town by nightfall or we’ll burn down your house,” threatened a quivering voice.

That night we had a meeting scheduled in Greensboro — about 50 miles away. The only bus which would get us there in time had left. We remained in Reverend Jones’ house, standing watch at the windows, while he rounded up three university students with cars who would drive us to Greensboro.

The three cars drove us directly to Shiloh Baptist Church in Greensboro, where the meeting was held. The church was crowded to capacity, and an atmosphere of excitement prevailed. Word had spread about what had happened to us and why we were late. All 18 of us sat behind the pulpit. After the usual invocation, hymn-singing, scripture-reading and prayer, Bayard Rustin, who is a particularly talented speaker, told our story. He interrupted it only to get one or another of us to rise and tell about a specific incident or experience. Then he continued. When he finished, the people in the crowded church came forward to shake hands and congratulate us. A number of the women had tears in their eyes. A few shook my hand more than once. As at almost all our meetings, there were not more than two or three whites in the audience.

Later, about to leave Asheville for Knoxville, Tennessee, I was arrested for the second time on the journey. No sooner had Dennis Banks, a Negro musician from Chicago, and I taken seats near the front of a Trailways bus, than the driver asked us to move. We refused, and within minutes police boarded the bus and arrested us.

In the courtroom where we were tried, I saw the most fantastic extreme of segregation in my experience — Jim Crow Bibles. Along the page edges of one Bible had been printed in large letters the word “white.” Along the page edges of the other Bible was the word “colored.” When a white person swore in, he simply raised his right hand while the clerk held the white Bible. When a Negro swore in, he had to raise his right hand while holding the colored Bible in his left hand. The white clerk could not touch the colored Bible.

Our case was over in a few minutes. Judge Cathey turned to the district attorney and asked, “Is 30 days the maximum sentence under the state law?” When the district attorney confirmed this, the judge said, “Then it is 30 days under supervision of the State Highway Commission.” It was a polite way of saying 30 days on the road gang. He then made a little speech which started, “We pride ourselves on our race relations here.”

It was several hours before Banks and I were released on bail. We never had to serve our 30 days on the road gang. When our attorney filed appeal papers, the state dropped the case, apparently aware that it would not hold up on appeal. We lost only one of the five arrest cases arising from the trip. As a consequence of that case, Bayard Rustin, Igal Roodenko and Joe Felmet served 30 days on the road gang

Tags

Jim Peck

Jim Peck is a former staffer for CORE, and now works for Amnesty International. He is currently active in demonstrations against draft registration. Following the recent testimony of Gary Rowe, Jr., undercover agent for the FBI in the Klan (and one of the men accused of assaulting Peck in Birmingham in 1961), Peck filed a $500,000 lawsuit against the FBI.