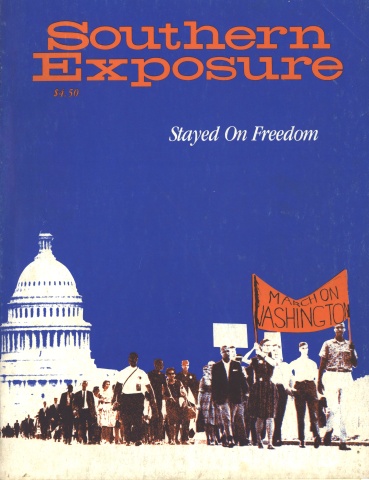

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

August, 1964: Imagine that you are a black high school student in Bogalusa, Louisiana. It is a hot, muggy Wednesday night. You are about to watch a play. The play will be performed by the Free Southern Theater, but not from a written script.

The play tonight is about Bogalusa itself. The cast includes not only the members of the FST but some of your classmates, many of whom have participated in protest marches during the summer. A huge crowd has gathered at the union hall despite the heat. It is as if the entire black community has come, plus the several CORE workers who have been in town, and others from neighboring towns.

From where you are standing you can see there are as many people outside as inside, even the windows are crowded with eager faces. Outside across the dirt road, the police chief leans against his automobile talking with several of his deputies. The chief is not sure what a play is, but he is present in case any “trouble” develops. Anyway, amidst the excitement no one pays attention to the police. The Deacons for Defense of Equality and Justice are also present. They had escorted the Free Southern Theater without incident from McComb, Mississippi, and will provide a protective caravan of cars tomorrow morning when the company leaves for New Orleans,

After a brief introduction by Gilbert Moses, who explains this will be an improvised play, the scenes begin. The play is about the demonstrations in Bogalusa that summer, about the violence in Bogalusa and the inflexibility of the mayor, his city council and the police in the face of that violence, and about the determination of black citizens to fight back, to fight for their rights and to take action to ensure their safety while protesting for their rights.

The audience responds to the subtleties, humor, truth of every situation as it develops on the makeshift stage. And you too respond though you are not sure this is a great play or that plays should be about something like this. The plays by the Central High School drama club in Bogalusa are certainly not like this. But nevertheless this play is about your life, your problems, what you have been through - and you have heard truths stated tonight which have only been whispered in Bogalusa. And you wished the police chief (who is probably outside wondering what all the shouting, laughter, excitement is about), the mayor, every white person in Bogalusa could be in the union hall tonight to see themselves portrayed as they really are. — Tom Dent*

Culture played an important role in the Movement. There was drama and poetry, exceptional photography and an abundance of good graphic design work. Tail-tale telling was raised to new heights (which is one reason it’s so hard for historians to get a clear idea of what the facts actually were). This highly developed storytelling tradition in the South serves as the foundation for the remarkable improvizational art of the preacher. Some of the finest political oratory ever created rolled from the rapturous lips of Movement pastors inspired by the passion of their congregations. And there was music! Organized and spontaneous, professional and traditional. People’s music. The people gave form to emotions too deeply felt for speaking by making songs, or shouting or humming or moaning—

I don’t know why I have to moan sometimes

I don’t know why I have to moan sometimes

It would be a perfect day, but there’s trouble all in my way

I don’t know why, but I’ll know by and by.

As we reflect on the role of culture in the Civil Rights Movement, we must be mindful of how easy and pleasant it is to make romance of the past. In romance, we tend to exaggerate the emotional extremes at the expense of fact. This is not a helpful tendency. However much fun it may be to recount tales of ancient glory and shame, the value in the examination of information about past events is to help us discover patterns from which we can draw lessons for the future.

A few general observations:

• Since art can stand no taller than the philosophical ground upon which it rests, the art work of the ’60s is limited by the philosophical shortsightedness of the Movement itself.

• The art and literature of black artists intellectually grounded in the period between 1918 and 1940 are generally superior to the work of artists from the ’60s because of the stronger philosophical ground that oriented the movement their work reflects.

• The interplay of ideas about culture and art that occurred during the ’60s is more important than the actual accomplishments of artistic work done. Consequently, the art is more important as historical data than as aesthetic product.

• The strongest art work is that which is most deeply rooted in the folklife and traditions of the people for whom the work is created.

• The connection between the content of the work and the audience is critical. The people are the ones who make the music and the artists are the instruments they play.

• The popular art, controlled by entrepreneurs whose interests are distinct from, if not contradictory to, the interests of the masses of people, has been more influential than anything Movement artists have yet created.

• Movement artists, like the Movement itself, tended to ignore the economic terms which limit and define possibility.

Now a summary of the experiences upon which these ideas are based.

It didn’t matter that most of the marquees were for second-rate skin flicks. It didn’t matter that we had said to each other time and time again, “Broadway’s a pointless exercise in decadence!” There we were! In The Big Apple! In spite of everything, my partner, Gilbert Moses, and I were standing in the busiest part of the Great White Way and excited to be there. There was romance and excitement that caught me by surprise.

Our object was to recruit people to join the effort to build the Free Southern Theater in Mississippi. Armed only with what we thought was the most important artistic idea of the decade, we were on the way to meet a group of actors. Of the several people we talked to that night, I remember one actor of exceptional ability. We’d seen him perform earlier that evening. He was just the kind of person we needed.

After we’d run down our naive but enthusiastic rap, the actor was almost as excited as we were. “You guys have come up with a great idea!” he said, almost bursting. “I wish I could come down there to work with you, but I can’t leave The City right now. I’M JUST ABOUT TO MAKE IT!”

Whenever I see that actor now, almost 20 years later, I can’t resist the impish impulse to ask, “Hey, man, you made it yet?”

How many times we were to hear that refrain.

That encounter typifies the problem of the arts and the Civil Rights Movement. We were caught up in and driven by forces we did not understand.

With the shameless arrogance of innocence, we charged ahead with little respect for the struggles of our elders. “They couldn’t have done much!” we told ourselves. “If they had we wouldn’t have The Problem to deal with, would we?”

Like most of the youths who got involved in the Movement, I labored under the mistaken idea that the only tiling wrong with America was that it didn’t live up to its own standards. This idea placed severe limits on what the Movement could accomplish. It was particularly bad for artists. To create art of sustaining value, the artist must be grounded in a comprehensive and coherent view of the world. Mastery of skill, craft and style cannot make up for faults in basic conception.

The Movement was a good thing. Some important changes were won as a result of it. But if we aren’t careful, we will make the mistake of separating the Movement from history. The ’60s are like the third act in a drama that begins with the end of the Second World War and will likely end with some other definitive event of world-wide significance like the fall of South Africa.

Act One of this historical drama starts with demands to integrate the armed forces in the fight against Nazism. Japanese-Americans are marched off to concentration camps in California. Then the pointless atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It ends with race riots in the streets and Joe McCarthy beating the bushes for Communists.

Act Two takes up with the undeclared war against “Gooks and Chinks” in Korea, includes the Supreme Court decision deposing the doctrine of “separate but equal” in favor of “all deliberate speed,” goes on to the Mau-Maus in East Africa and ends with the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Act Three opens with the independence of Ghana, the sit-ins spreading like a prairie fire in brown grass, and jumps to the Freedom Rides. The price is paid in blood, but great moral victories are won. Legal sanction for segregation is withdrawn. It is an important but limited victory. With the March on Washington the initiative passes out of the hands of the Movement into the hands of a liberal/labor coalition that serves as the “loyal opposition” to Corporate America. Official Washington consolidates control over Movement leadership by putting them on the payroll in the War on Poverty. Those who can’t be isolated, forced into exile or jailed are declared to be outlaws and are killed with or without the cover of law. Act Three ends with the assassinations of Malcolm X, the Panthers and MLK.

Act Four goes from the Poor People’s March on Washington to Andy Young’s rude end at the UN.

The resurgence of the Klan starts Act Five and some cataclysmic event like the fall of South Africa ends it.

As we struggled through what I’ve called Act Three, what we sought to be free from seemed clear. But, in all our terribleness, when the Movement tried to define the freedom to . . . the confusion spread all around. Answers to questions either faded off into infinite shades of gray or fell into bold and outrageous absurdities which were to be accepted on faith.

The Movement was not the product of a concept or program of social change. It was a spontaneous response to intolerable conditions. A great many people were mad enough to act simultaneously. It was the greatest strength and the greatest weakness at the same time. No single decapitating blow could stop it. But, as every good streetfighter knows, if you go into a fight mad, you’ll probably lose. There’s no guarantee that good thinking will win the fight, but it’s almost certain that bad thinking will lose it.

It could not be said that our Movement was distinguished by the quality of its thought. It was dominated by philosophic chaos! That condition was probably one of the main reasons that the pragmatists were able to carry the day, pragmatism being as close as you can get to having no philosophy at all while maintaining a semblance of rationality. In profane exaggeration of the idea of democracy, anybody who didn’t already know a philosophy that would suit his or her fancy was prompted to invent a new one.

In this philosophical disorder, Movement leadership — caught in a compelling sense of urgency — was defenseless before the aggressive inadequacies of pragmatism. By the spring of 1963, a coalition of national civil-rights organizations held more power than had ever been achieved by a group of black persons in America. The best among them were awed by the power and carried it with a certain virginal innocence. But, as is often the case with virgins, the confrontation came. On one hand they faced formidable political, economic and police sanctions; on the other hand, they saw what appeared to be unlimited access to government resources.

In the made-for-TV movie about Martin Luther King (played by Paul Winfield), there was at least one brief moment that had the ring of truth. Martin is in the White House trying to get LBJ to support some pending legislation. Martin asserts the justice of his cause.

LBJ: It’s not about justice, Martin. It’s about power. You give me a campaign bigger than Birmingham and I’ll give you a Civil Rights Bill.

MLK: (Aghast) Dozens of people could be injured or killed!

LBJ: (Turning mournfully to look out the window at the Washington Monument) I order hundreds of people to their deaths every day, Martin. . . .

According to the film, that’s how the Selma-to-Montgomery March started.

The altruism that had characterized the early ’60s faded into frustration, and frustration gave way to cynicism. By 1965, the Movement was effectively finished. A small but important minority, recognizing the insufficiency of reform, moved towards revolutionary ideologies. The majority, however, simply relinquished their claims to the high ideals that brought them to the Movement. Considering that they had paid their dues, many decided to step off the battlefield to join the establishment. Others simply dropped out.

We who work in the arts are supported by or limited by the social-political environment in which we work. When the political movement is doing well, many options and possibilities open up for us. Like every progressive political movement, the ’60s liberated a great surge of creative energy. Regressive political trends tend to force the creative impulse into isolation. Dread, doom, fear, gloom and themes of sensual and erotic decadence juxtaposed to strident militarism come to the fore. Inevitably, as our Movement lost its orientation, so did most of our artists.

The general trend is especially evident in music. Music was one of the more important organizing tools of the Movement. It was used to inspire, educate, demonstrate, propagate and raise money. Every meeting had to begin and end with a song. The SNCC Freedom Singers became a popular attraction on campuses and in concert halls everywhere. In some cases traditional musicians appeared with the Freedom Singers. More often they traveled with seasoned performers like Pete Seeger and Dick Gregory. In order to structure the relationship between musicians and the Movement, the Folk Music Caravan was organized to produce concerts, festivals and other music activities in the South while continuing to work on fundraising.

The widespread interest in folk music that developed was reflective of the potency of the grassroots social movement. It was a perfect analogy. The power of spontaneous social movement, like the power of music, is more intuitive than rational. To be a part of a group of hundreds or thousands of people, marching together, singing together, united in pursuit of a purpose greater than each, yet valuable to all, is a compelling experience. It is humbling and uplifting to hear the voice of 10,000 people come out when you open your own mouth to sing. Artists who participated in such experiences were always profoundly affected, and it influenced their work.

The Movement set the tone for the popular music of the day, too. Almost all of the popular music acts had one or two recordings of “message” music. Some acts, like the Impressions, built large portions of their repertoire on Movement themes. Jazz artists like Nina Simone made extensive use of Movement material. Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite with Abby Lincoln on vocals is classic. One of the reasons that the Little Rock school incident is fixed so firmly in my memory is that bassist Charlie Mingus satirized the governor of Arkansas so well with his Fables of Faubus. Aside from the Freedom Singers and the Folk Music Caravan, the Free Southern Theater was the only organized cultural program that developed in the Southern Movement.* Theater is so verbal and so organizationally complex that it’s especially important to be clear about what you’re trying to do. At the FST we were forced to think about the Movement systematically. If we were to portray relevant themes and Movement people, we had to find out what gave them their particular character. We had to look for artistic models.

At first, we overlooked one of the best sources — the wealth of oral literature created by Afro-Americans — because it didn’t fit into our idea of what theater was. There are parables and animal stories for teaching children, tall tales and bawdy rhymes for adults only and everything in between. This highly developed storytelling tradition in the South also encompasses the remarkable art of improvisational preaching, of which Martin Luther King, Jr., was one of the most notable masters.

Folk art is that area of art limited least by the shortcomings of Movement thought. Because it boils up from the realities of life faced by rural and urban workers, folk art is largely insulated from the extravagant abstractions of current theoretical trends.

Maybe it did sound hip as it dripped from the lip of some silvery-tongued orator, but most of the Movement mass meeters, being well-practiced churchgoers, knew that it takes just about as much energy to turn a pretty phrase as it takes to turn a shovelful of dirt.

The Movement gained far more from the rural and urban workers than it gave back as improvements in the quality of life. The main troops of the Movement were from the rural and urban working classes. The main leadership and most of the dominating ideas came from black professionals and small property holders. As it turned out, the classes which provided the leadership were the ones to get the main benefits also.

What is true in the political and economic sphere is generally reflected in the aesthetic sphere. Since the ideas of the Movement did not correspond to the realities that people had to live through, these ideas never did filter down and take root among the masses of the people. Little damage was done to the folk culture.

The literary product generated by the Movement is voluminous. Everybody tried to write poetry. There are dozens of biographical essays. Several collections of letters, diaries, reports, etc., have been assembled. Fiction, long and short, is relatively rare.

It may be that the most important art and literature from the period have not yet been published or distributed widely. Based on the available material, it seems that there is more historical than artistic value to be found in the cultural product of the ’60s. Of the material that has been published the most important are those unself-conscious personal forms: letters, diaries, reports, etc. The record of direct experience will prove invaluable as source material for future work.

A lot of exceptional photographic and graphic design work v/as done during the Movement for two reasons. First, the graphics industry, like the music business, is highly structured and is a well-developed part of the mass media. Photographers and graphic artists who understand and have access to it can practice their craft and make adequate income at the same time. Second, graphics is not verbal and is therefore less threatening. Like musicians, graphic artists may use words but they are not dependent on them.

Because of the large investments required, large corporations operate virtually unchallenged in TV and film industries. Blacks who become involved to a significant degree tend to be those who accept the superiority of a “market to be exploited” over an “audience to be served.” The main thing that happened in consequence of the Movement was that a few black people got jobs in the industry. When the Movement began to fade, so did the strong image of black people from the screen.

When the Movement was in the press every day, it acted as a magnet to people in the commercial entertainment industry and all other levels of cultural and artistic endeavor. As the Movement lost its orientation and focus, the flow of influence was restored to its reactionary norm. Artists, instead of being drawn into the orbit of the Movement, deserted the people’s struggles for the alluring illusions of the Great White Way and Tinsel-Town. The same process that robbed the Movement of its leadership, robbed the people of their artists. In too many cases the leaders, artists and scholars did not simply desert the field of struggle but actually joined the ranks of those who profit from the people’s misery.

The most significant literary work done by people from this period has been done in the essay. Here is where we wade through the swirling torrents of our experiences in search of coherent formulations and our ideas are exposed to critical evaluation.

The Free Southern Theater experience fits within this general context. What we have done is good, but the artistic and political potential of our work is far greater than anything we have actually been able to do. We have not created works which adequately illuminate those values or actions which the masses of people recognize as being helpful and supportive to their struggle to improve the quality and character of our collective life. Although there are moments when we rise above it, our work has been dominated by private, ego-centered visions. Even as we address the problems of the Movement, we have seldom grasped the social, economic and historical essence of the problems we face.

At the same time we have not understood the compelling impact of economics on art. Qualitative improvement in the work requires study and practice; these take time and time costs money. The FST, again, in correspondence to the general trend of ’60s survivors, has been supported primarily by grants and contributions from foundations and government sources. This is not viable.

The political, economic and social goals of those who provide the financial base and control the process must correspond to the aims and goals of the artists. In turn, these must correspond fundamentally to the needs of those who comprise the critical audience. If these corresponding relationships don’t exist, then the efforts of the artists are ultimately nullified. These two problems, the philosophic and the economic, form the axis that identifies the shortcomings of art and cultural activity in the Civil Rights Movement. The challenge for the future is to meet and solve these problems.

The longer it takes for us to gain a firm grasp of these problems, the longer it will take us to meet the responsibility before us in this historic moment. The result will be an unconscionable delay in the coming of that day when the dreams of our grandparents and their grandparents before them shall come true. If we fail in this historic moment, then the legacy of suffering we pass to our children will be increased. Our failure would increase the ultimate cost of the struggle and will postpone the time when the social order shall be transformed. Future generations wait to see if we will shoulder our share of the burden. There is no question about whether we will ultimately win. The question is how much it will cost.

* Excerpted from Freedomways, Volume 6, Number 1 (1965).

** Liberty House/Freedom Co-ops produced and distributed handcrafted items. To a certain extent the Freedom Schools participated in the promotion and development of cultural activities. In the North, Operation Breadbasket developed a choir and a band. The Last Poets were a product of Movement activity in the North. The Folk Music Caravan was succeeded by the Southern Grass Roots Music Tour, which continues to produce festivals and tours.

Tags

John O'Neal

John O'Neal was a co-founder and director of the Free Southern Theater for almost 20 years. He is currently touring the nation in his one-person play, Don't Start Me Talking Or I'll Tell Everything I Know: Sayings from the Life and Writings of Junebug Jabbo Jones. (1984)

John O ’Neal is co-founder and director of the Free Southern Theater in New Orleans. O’Neal’s one-person play, “Don’t Start Me to Talking Or I’ll Tell Everything I Know, ” is currently touring the country. (1981)