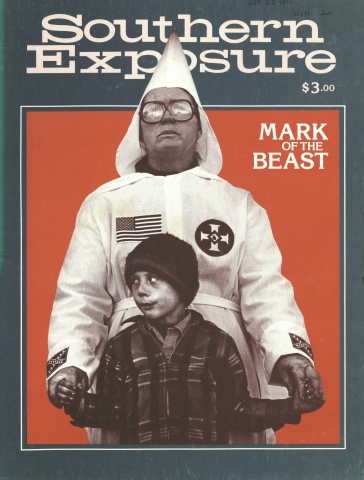

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

The tension in the Muscle Shoals, Alabama, Omelet Shoppe suddenly was electric that night, last October 29, when the two black ministers entered and sat down in a booth near the cash register.

At the counter, every seat was filled by white Klansmen, dressed in street clothes and wearing baseball caps bearing the KKK emblem.

When the Klan members noticed the black men sitting there sipping coffee, voices lowered for a few moments, then their conversation became loud and boisterous. The word “nigger” repeatedly echoed across the dining room.

“It was like a scene from a 1960s sit-in,” said a federal officer who later investigated the pick-ax handle assault on the ministers. “Every patron knew something terrible was about to happen. But it was like everybody was paralyzed, except the Klan members. Of course,” the officer said, “the ministers weren’t there to prove anything. They were just there to have a cup of coffee.”

It was sheer coincidence that the Klansmen were there that night. They had just come from picketing TV station WOWL in nearby Florence. They were protesting because it was airing Freedom Road, a film starring Muhammad Ali.

The Reverend Otis Nelms had come to the Omelet Shoppe in his home town of Muscle Shoals that night to chat about church matters with the Reverend Roger Pride from the neighboring community of Courtland.

Abruptly, Klansman Ricky Lynn Creekmore pushed away from the counter and strode to the booth, glaring down at the two ministers. He tossed a small, white Klan “calling card” into Nelms’ lap.

Nelms looked at it. His eyes met Creekmore’s.

“Is this for me?”

“It’s for you,” Creekmore replied. He walked back to the counter where the other Klan members were watching. For a few minutes the conversation at the counter continued — more loud talk which included racial slurs.

When the black ministers rose to leave, the Klansmen surrounded them and elbowed them as they went outside to the parking lot. A patron of the restaurant ran to the phone and called the police, but by the time the wail of sirens was heard in the parking lot, the Klansmen had grabbed pick-ax handles from their cars, assaulted the two ministers and bashed in the side of their automobile. The Klansmen fled as the police cruisers arrived.

Later Creekmore and Charles Jethro Puckett, identified as one of those swinging a pickhandle on Pride, were arrested. They pleaded guilt in federal court and were sentenced to a year in prison. At least three more Klansmen — perhaps five — are sought by authorities on assault charges.

Whenever members of the “new” Klan movement march these days, violence — the Klan’s traditional ally — may walk just a half a step behind.

In 1971, the Ku Klux Klan had slightly more than 4,000 members, according to FBI estimates — a sharp drop from the 16,810 Klansmen which a congressional committee had reported in 1967. But nine years later, in 1980, the Ku Klux Klan is coming back. The Anti-Defamation League of B’nai Brith estimates Klan membership at around 10,000. Officials of the U.S. Justice Department say the 10,000 figure “may be on the low side.” For the year ending September, 1979, the Community Relations Service of the Justice Department reported a 450 percent increase in Klan-related activities from the year before. In the first two months of this year, the CRS has reported that the number of Klan incidents in communities across the nation is still on the rise.

Always, it seems, violence follows in the shadow of the hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan: killings, shootings, beatings, vandalism. “There is a direct corollary between the increased Klan activities in the streets and the upturn in violence related to the Klan,” says William Gralnick, director of the American Jewish Committee office in Atlanta, and a constant Klan watcher. “We show a clear trend — an increase in serious incidents,” echoes Gilbert Poma, who is director of the Justice Department’s Community Relations Service in Washington. “I fear there will be more violence.”

While most of the acts of physical violence have occurred in the South, there have been cross burnings and gunfire in some Northern communities in recent months. But the most publicized incidents of violence in recent months both occurred in Southern communities: Greensboro, North Carolina, and Decatur, Alabama. A group of Klansmen and neo-Nazis gunned down and killed five radical anti-Klan protestors in a broad daylight shootout on a Greensboro street in late November. A few months earlier, in Decatur, two blacks and two Klan members were shot down, again in broad daylight, in a bloody street confrontation.

Other incidents in 1979 include these acts of violence:

· In Sylacauga, Alabama, a few months before the Decatur assault, a Klan klavern declared war on two black leaders. Gunshots were fired into the homes of Charles Woods, state president of the NAACP, and local NAACP head Willie James Williams, a retired Army sergeant. Twenty Klansmen were rounded up and charged with federal counts of violating the civil rights of citizens through acts of terrorism. In addition to seeking to intimidate the NAACP leaders, the Klan klavern also sought to become the enforcer of community morals: gunshots blasted the house where two interracial couples were living, and a man whose neighbor told the Klan he had engaged in child abuse was given a “nightride” and flogged. Thirteen of the Klan members were either convicted or pleaded guilty to civil-rights charges in their reign of terror.

· In Cullman, Alabama, in September, 1979,aKlanklaliff (vice president) called a rally to protest because two Vietnamese refugees had been employed at a local textile mill. The klaliff, Clarence Eugene Brown, also employed at the mill, threatened the Vietnamese workers on two occasions and, according to federal prosecutors, finally warned them: “If you come back to work I’ll kill you.” Later, in the company of another Klan member, 300-pound Myron (Tiny) Marsh, he pulled a knife and menacingly waved it at them, according to testimony in the trial at which Brown was convicted of violation of civil-rights laws.

· In Carbon Hill, Alabama, May 8, police instituted a nine p.m. curfew after a black man, James McCullman, 24, was shot in the face at a Klan gathering. A man at the meeting, Roger Dale Patmon, 34, was charged with assault with attempt to commit murder. A Klan leader praised Patmon for behaving “admirably.”

· In Tupelo, Mississippi, opposing marches between civil-rights activists and Klan members erupted into a fight last June when a KKK member began beating a black with a heavy chain.

In every one of those situations and in dozens of others that have occurred from California to Georgia, Texas to New Jersey — there is the potential for the sort of bloodshed that came in Greensboro and Decatur.

A tiny independent Klan faction in North Carolina was involved in the worst episode of Klan violence in more than a decade. There had been little public activity in North Carolina’s Piedmont area before two small Klan factions in the Winston- Salem area began competing for attention early last year. They demonstrated, held news conferences, put displays of Klan regalia in public libraries and burned crosses. An integrated group of protestors — some of them members of the Communist Workers Party — marched on a Klan meeting in the small town of China Grove in July, chanting “Kill the Klan!” They burned a Confederate flag and forced armed Klan “security guards” to retreat into a building where they were preparing to show the film The Birth of a Nation.

The Communist Workers Party, whose college-educated members had had only limited success in organizing workers in the Piedmont area’s textile mills, announced plans in mid-October for a “Death to the Klan” rally in the black community of Greensboro. The group challenged the Klan to appear and told police, in a public statement two days before the march, to “stay out of our way.”

Police say they planned to provide security for the march, which was scheduled to start at noon, but most of the officers assigned to it were still at lunch when a surveillance officer reported, shortly after 11 a.m., that a nine-car caravan of Klansmen and neo-Nazis was headed for the anti-Klan rally. The Klan caravan drove down a narrow street into the midst of the gathering protestors, who were shouting “Death to the Klan!” The Klansmen began shouting “Nigger,” “Kike,” and “Communists,” according to witnesses. Some of the protestors began hitting the Klan cars with their signs, and a shot was fired.

The Klan members were not hit and almost all the shots that followed came from the Klansmen and their Nazi friends, several of whom got guns from the trunk of the car and coolly fired at the demonstrators. TV cameras recorded the deaths, including Klan members firing point blank at fallen protestors. Five members of the Communist Workers Party were killed, and another CWP member, Dr. Paul Bermanzohn, was shot in the head and remains partially paralyzed today.

Both sides blame the tragedy on the police. “This was an organized, planned assassination, carried out with the cooperation of the Greensboro police,” said Bermanzohn, 30, who had become involved in left-wing politics when he and two of the men killed were students at Duke University Medical School.

“We were set up,” said Virgil Griffin, the Klan Grand Dragon who was in the caravan. Several of the Klansmen said after the shooting that they had planned only to heckle and throw eggs at the marchers. “We did not expect a fight. If we had, we wouldn’t have had our guns in the trunk,” Griffin said. But, he added, “We don’t believe Communists have a right to be on the streets of Greensboro or anywhere else. I don’t see the difference between killing Communists in Vietnam and killing them over here.”

The deaths in Greensboro gave added impetus to the organization of an anti-Klan network, which conducted a giant march in that city on February 2. The march attracted several thousand people from across the eastern United States. The Klan stayed home.

The seeds of a gun battle at Decatur last May had been planted a year before and had been nurtured to maturity by the Klan. The first sign of trouble came in 1978 following the arrest of Tommie Lee Hines, a severely retarded black, on charges of raping three white women. Despite considerable evidence that he was mentally incapable of driving a car involved in the crimes, he eventually was sentenced to 30 years in one of those cases.

After blacks staged several marches protesting Hines’ conviction, Klan Wizard Bill Wilkinson recognized Decatur as a target for national publicity and announced plans for an August 12 rally. Among the 7,000 whites who turned out — only 50 of them were robed Klansmen — none could have known the truth of Wilkinson’s words when he said, “A race war is coming.” Tension in the town continued to build last February when about 150 robed Klansmen taunted city officials with a pick-up motorcade through the middle of town, waving shotguns and pistols — in defiance of a new ordinance banning weapons in demonstrations. On May 26, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference marched to protest the Klan, and the KKK put on their robes and loaded their guns for a counter-march.

In early afternoon it happened.

“Help me boys, I’m shot!” shouted David Kelso, 24, a white-robed Klansman, moments after 50 black protestors ran head on into a barrage of 200 Klansmen at a downtown street corner.

“Fall back! Fall back!” someone screamed as three others — Larry Lee Smith, 41, white; Berdice Brown, 27, black; and Berdice Kildo, 41, white — stumbled bleeding to the ground.

The violence stunned the city. Two days later, 200 heavily armed Klansmen headed by Wilkinson rallied at the city hall and burned a seven-foot cross while Wilkinson was telling the town, “Arm yourselves against the niggers.”

Such racist militancy has led Wilkinson to become known as the Klan leader whose organization is the most aggressive in recruiting new members. Justice Department spokesmen refer to him as “wild” and “dangerous.” The Anti-Defamation League says he is “lawless.” He apparently is ready to move into any community where there is racial difficulty to try to organize a Klan chapter. Other Klan leaders, unhappy with his tactics and jealous of their territory, call him an “ambulance chaser.”

A stumpy man who wears glasses, Wilkinson is a tenacious advocate of white supremacy, an adequate public speaker and a hard-nosed businessman. He was recruited into the Klan in 1974, when he was 34, by David Duke, who is nine years his junior. Later in 1975, the two men had a bitter break involving a dispute over funds Duke collected during a rally organized by Wilkinson. Wilkinson initiated his own “empire” — called the Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan — named himself Imperial Wizard and opened headquarters on a 10-acre plot he owns in Denham Springs, Louisiana, just outside Baton Rouge.

Today, Wilkinson flies his own plane (“The Klan bought it for me”) to rallies and marches. He often goes armed, and he has been arrested four times in the last two years, though convicted only on a misdemeanor for parading without a permit. On at least two occasions, he was present at Klan events when gunfire broke out.

Among other national Klan leaders, Robert Shelton has the largest membership — but he has served time in federal prison for failing to give Congress Klan records, and much of the fire seems drained from his faction. He calls Wilkinson “foolish” for “taking people out in the streets with guns and getting them arrested.” Shelton, 51, the Imperial Wizard of the United Klans of America, is a veteran of the violent 1960s in the South, and was the best-known KKK figure for many years. His organization’s membership reached an estimated 15,000 before he was sent to federal prison in 1969.

The FBI admits today that Shelton was accurate in complaining his Klan was infiltrated, harassed and undermined by a Cointelpro campaign of “dirty tricks.” Years of controversy and conflict have now made him guarded around reporters, suspicious even of his own members (“We give all new members a lie detector test”) and jealous of other Klan competitors (“Duke runs a mail order Klan and Wilkinson is irresponsible.”) A tough, taciturn man, he is less media-oriented than the “new” Klan leaders, but observers still say his United Klans of America has more active members than other groups. Shelton’s headquarters are now located in a two-yearold 7,200 square foot metal building on a dirt road in the piney woods north of Tuscaloosa; the land is owned by the Anglo-Saxon Club, a Klan front, of which Shelton is president.

If the Ku Klux Klan has a “new” image behind the old hood, it is largely because tall, muscular, mustachioed David Duke has become something of a “media personality.” An attractive college graduate who operates as Grand Wizard of his Knights of the Ku Klux Klan — based in Metairie, Louisiana, just outside New Orleans — Duke delivers a carefully polished pitch on “white rights” that often has made him shine against TV newscasters and interviewers who come unprepared, expecting him to spew traditional racial hate, slurs and slogans.

Duke publicly disavows Klan violence, but he paid a $500 fine last year for an inciting-to-riot conviction and is still on probation. A recent edition of his newspaper, The Crusader, called for freeing the “Greensboro 14” Klan and neo-Nazi members charged with gunning down the five CWP members. He has pledged to raise money for their lawyers, and he allows his members across the country to make their own rules about guns.

Duke’s Texas Grand Dragon, Louis Beam, has a Klan chapter that is armed and trained as a paramilitary unit. Klan watchers like Irwin Suall, director of fact-finding for the Anti-Defamation League, say they think Beam’s Texas Klan organization has “the greatest potential for violence” of any in the country. Beam provides a full military training program — using surplus Army ordinance — to Klansmen who join his Texas Emergency reserves.

He is 33, a Vietnam War veteran and a graduate of the University of Houston. He boasts that Klan members from nearby Fort Hood say the training his “army” provides is “at least twice superior to what they get at Fort Hood.” Beam’s Klan members hand out “Nigger Hunting Licenses,” and his mimeographed Klan newspaper The Rat Sheet features a drawing — captioned “the Only Way” — of a masked Klansman with a U.S. flag in one hand and a rifle in the other.

Former Duke associate Tom Metzger, the Grand Dragon of his own Klan realm in California, has organized some of his followers into a black-uniformed, helmeted “security force” which has had several violent clashes with groups of leftist protestors. During a clash in Castro Valley on August 19,1979, 30 anti-Klan protestors fought Klansman wielding clubs and plywood shields, sending one Klansman to the hospital for treatment of a head injury. More recently, Metzger’s men were involved in a street fight at Oceanside, California.

Klan-related violence is not limited to the South and West. In February this year, in Barnegat, New Jersey, one of Duke’s followers, Aaron Morrison, 53 18, was sought by police for questioning regarding some shots fired into a black home. Police say they found a cache of weapons — including four high-powered rifles, seven knives, brass knuckles and a blowgun — when they searched Morrison’s home.

The resurgence of the Klan and its potential for violence cannot be ignored. They are real, as we learned firsthand in the course of a four-month newspaper series for the Tennessean. After interviewing a Klan leader in New Orleans, a reporter and photographer found that the four tires on their car had been slashed.

There is nothing new about the economic frustrations, racial tension and crude anti-Semitism that contribute to the growth of the Klan, nor is there anything new about the message of the Klan in the 1980s: racial hatred. What is new and frightening is that this message is being delivered by Klan leaders who are becoming expert at generating publicity and manipulating the media, and who are promoting the “new” Klan as a family affair. By appearing on national television and inviting women and children to join, the “new” Klan hopes to make itself respectable. But there never was and never will be a way to make the Klan and its racism respectable.

There are those who fear that the “exposure” of the “new” Klan will only encourage people to join, or will promote anti-Semitism, or magnify white racism. But history shows that to wait until there are 20,000 Klan members — and until the corruption again pervades society — is to ignore a cancerous growth until it cannot be arrested without major surgery. The Klan is most dangerous when it is left alone and its leaders — old and new — can spew their racist venom unchallenged. That is when the Klan can poison a community and the country.

This article is adapted from a series on the Klan written by staff reporters Kirk Loggins and Susan Thomas of the Tennessean in Nashville. Photographs are by Nancy Warnecke, and the material here, in the box on this page and on pages 91 -92 are reprinted by permission of the Tennessean’s publisher. The 14-part series was reissued by the newspaper in a tabloid and is available by writing publisher John Seighenthaler at 1100 Broadway, Nashville, 37202