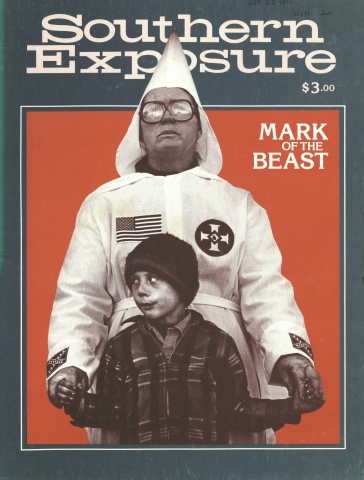

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

November 3, 1979 — Caesar Cauce, Jim Waller, Bill Sampson and Sandy Smith lay dead; Mike Nathans would be dead soon; several other Communist Workers Party (CWP) members and supporters were seriously wounded. Klansmen and Nazis had made the assaults, but the whole incident had the distinct earmarks of state complicity.

Police had known that armed Klansmen were driving into Greensboro, North Carolina, to confront the CWP at its “Death to the Klan” march. A few days earlier, they had released information about the march’s starting point to a Klan representative, but continued to press CWP heads to leave their guns at home. On the day of the scheduled march, while police inexplicably sat two blocks away, Klan and Nazi cars entered the area where demonstrators were gathering and opened fire on the CWP members.

As a response to the murders, the CWP called for a funeral-protest march, to be held in Greensboro on November 11. Some CWP members had carried guns the day of the murders, and party spokesperson Nelson Johnson said that, as a result of the killings, the CWP would never again disarm its marchers. He believed the police had deliberately failed in their duty to protect the marchers.

Before long, the CWP was not the only group looking towards government agencies with anger and suspicion. While CWP members were making plans for their funeral march, an assortment of human-rights organizations chose November 18 as the date for a religious service and a peaceful, unarmed demonstration to protest the killings. These groups included the Greensboro Pulpit Forum (a black ministers’ group), the Equal Rights Congress, Greensboro Coalition Against the Klan, the North Carolina Chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union and the Southern Conference Educational Fund.

But other forces besides these human-rights organizations were making their presence known in Greensboro in the days following the massacre. A “conciliation” team of the Community Relations Service — a little known agency of the United States Justice Department — had invited itself into the city. The team’s mission, ostensibly, was to help maintain civil order, but the actual effect of its activity was to sow seeds of dissension among the organizations trying to provide a nonviolent alternative to the CWP’s armed funeral march. Ultimately these factors forced the abortion of the planned November 18 gathering

The Community Relations Service (CRS)team was headed by Robert Ensley — a 51-year-old black agent whose efforts had already proved highly successful in previous agency “interventions” in northern Mississippi, Louisville and other communities across the South. Ensley says that when his Atlanta-based team arrived in Greensboro, the police were disorganized and “did not know at what level or who had the responsibility for doing what.” The CRS team immediately began holding daily “briefing sessions” with the police and other government agencies, discussing with them what steps to take to keep the lid on a volatile situation. The initial reports of the killings, including televised pictures of Klan and Nazi members firing on defenseless demonstrators a few yards away, led to a unanimous outcry from the media, human-rights organizations and average citizens — all directed against the irresponsibility of police authorities and the unrestrained brutality of racist organizations. The pressure on the police and city officials to account for their failure to stop the Klan seemed destined to intensify as groups issued statements and called for demonstrations. But within two days, following the arrival of the CRS “conciliators,”the focus of attention shifted to the violent rhetoric of the Communist Workers Party, and news stories began describing the killings as “a shootout” between “two extremist organizations.” Increasingly, anyone critical of the Klan murders or the city’s handling of the event was linked to the CWP and their admittedly provocative rhetoric.

Ensley said his agency plotted a “contingency plan” to cope with various responses in the community. But it soon became clear that the purpose of the plan was not to promote civil order by preparing protection for the participants in the nonviolent November 11 and 18 rallies; instead, these government agencies worked to scare off potential marchers with images of more “violent confrontations” and to divide one group of actors against another — ministers against “leftists,” local leaders against national organizations, students against community residents.

For increased efficiency, Ensley and the CRS team divided responsibilities among the various government agencies. The team’s own role was to keep tabs on the college student population, while the Greensboro Human Relations Commission and the North Carolina Human Relations Commission were assigned to contact high school students and local leaders before the November 11 funeral march. The message they used was essentially the same to each audience: “Beware, there may be violence.”

Ensley’s first task — a relatively simple one — was to discourage local college students (mainly at A&T State University) from participating in the November 11 march. Most of the students were anxious to express their outrage over the murders, yet they feared further violence and, very often, were leery of becoming involved with a Communist group. Ensley’s message played on those fears. Lynn Wells, a Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF) organizer, recalls that Ensley told the A&T students, “Oh, we’re not telling you not to take a position. We’re not telling you not to march. We just want to tell you that on Sunday there will be 5,000 National Guardsmen, there may be a state of emergency — and all of the guns will be aimed at you.”

Ensley remembers telling the students, “If you are going to get involved, get involved on your own terms.” He says. “I tried to give them some idea about the role of the National Guard and the state police and the sheriffs department.”

These “warnings” effectively built on memories of the 1969 National Guard siege of an A&T dormitory. One student, William Grimes, was killed during that siege.

Largely as a result of CRS activity, very few students marched on November 11. And the National Guard, together with state and local police almost outnumbered the approximately 1,000 demonstrators.

Having successfully undermined the funeral march, CRS began orchestrating a covert intelligence operation aimed at sabotaging the nonviolent religious service and rally planned for November 18. Although it is difficult to obtain hard proof about who was behind each instance of spying and intimidation, the tactics used were astoundingly similar to those the FBI and the CRS together directed during the 1960s against such figures as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., James Forman and Fred Hampton. These tactics included anonymous phone calls, red-baiting, spreading rumors and secret displays of gun caches and government files on various activists (see box on COINTELPRO.)

Vital to the success of the planned November 18 gathering would be the support — and participation — of local black ministers. Without their involvement, the tensions in the city and disagreements with the CWP’s use of arms would discourage many members of Greensboro’s black community from taking part in the service and rally.

No sooner did the ministers start making plans for the service they were sponsoring than they began receiving clandestine phone calls and unsolicited advice from city officials saying that their efforts might result in violence. This particularly alarmed the ministers, who had envisioned their service — and, initially, the subsequent rally — as a positive alternative to the CWP funeral march. While the deaths shocked and grieved the ministers, they — like many other human-rights advocates — strongly opposed the CWP’s willingness to bear arms and feared that the CWP would provoke confrontations.

On November 13, just one day after the ministers had publicly announced the service, Reverend George Gay of the Greensboro Pulpit Forum began to receive threats against his life. Another minister belonging to the Pulpit Forum — Reverend George Brooks — said that his support for the November 18 rally diminished after supposedly “leftist” groups indicated to him a willingness to disrupt the rally. “These people were only talking about being vindictive and seeking revenge,” Reverend Brooks said in an interview with Jim Lee, director of WVSP Radio in Warrenton, North Carolina. “They were not interested in any kind of real display of concern other than to show they would be militant. . . . They said . . . that you all go and have your church meeting, but stay there cause you’re going to need to pray for the dead.”

Somebody (the ministers refused to say who) also took several ministers aside and showed them caches of weapons supposedly belonging to “leftists.” The ministers were also shown secret government files on several key organizers of the rally, including SCEF’s Lynn Wells and Jerome Scott of the Equal Rights Congress. The files alleged that Wells and Scott were Communists — an allegation which tarred them with the same brush as the CWP and undermined the ministers’ confidence in the rally’s organizers.

The result of this covert intimidation and innuendo was predictable. First, the ministers announced that the service would be held completely separate from the rally; that they disassociated themselves from the rally and its organizers. Then they canceled the service altogether, a move which sealed the fate of the whole event. The Equal Rights Congress — a key sponsor — withdrew its support of the proposed rally. A flurry of other cancellations followed until finally the rally was “postponed.” Kelvin Buncum, A&T State University student body president, blamed the postponement on “lack of community support.” But while there were genuine fears in the community about a possible recurrence of violence during the rally, to a large extent the dwindling local involvement was caused by a divided leadership — a leadership whose members were effectively splintered and played off against one another.

The damage done was not merely the immediate effect of the postponed rally; the suspicion and discord built up during this period would remain a stumbling block for civil-rights organizers in the area during the months to come. Only through great effort was unity achieved for the massive February 2 demonstration sponsored by the National Anti-Klan Network. That rally not only protested the five murders, but also commemorated the twentieth anniversary of the Greensboro sit-ins, which many recognize as the birth of the 1960s civil-rights movement.

Although the CRS and other government agencies did not succeed in thwarting the February 2 Mobilization, their failure was not from lack of trying. On the contrary, the orchestration of covert activities escalated during December and January. It gradually became clear to many activists that — despite government denials — covert intelligence operations are still being used to derail human-rights and civil-rights movements in this country. It also became clear that the CRS is being used as a crucial weapon in this operation.

What is this innocuous-sounding Community Relations Service? What was it created to do, and how and when did it start being used as an intelligence-gathering and information-sharing operation?

Gilbert Pompa, director of the Community RelationsService, often has to answer charges that his agency gathers intelligence and is involved in activities disruptive to the civil-rights and human-rights movements. These critics, he replies, just don’t know the agency’s mandate.

CRS was established as a result of Title X of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 “to provide assistance to communities and persons therein in resolving disputes, disagreements or difficulties relating to discriminatory practices based on race, color or national origin. . . Agency staff were supposed to mediate or conciliate problems in racially troubled communities with the goal of upholding the endangered rights of minorities. Congress denied CRS any investigative or prosecutorial functions. In fact, by placing the infant agency within the Commerce Department, Congress deliberately isolated the Community Relations Service from these functions of the Justice Department, which was responsible for enforcing the new Civil Rights Act.

In a major speech on March 30, 1964, supporting the passage of the Civil Rights Act and describing how CRS would function, Senator Hubert Humphrey gave the following example:

Individual restaurant or hotel owners may be reluctant to admit Negroes unless assured that their competitors will do likewise. Through the good offices of the Community Relations Service, or of comparable state or local organizations, it may be possible to achieve agreement among all or substantially all the owners. Failing that, it may be necessary to sue a few holdouts - let us say, as an example, under Title II — while relying on agreement of the rest to act voluntarily if the suit is successful.

Thus, it is very important to realize that CRS was established to function as an aid to civil rights struggles — not as a means to thwart and disrupt them.

CRS followed its original mandate, as far as we know, until 1966, when President Johnson proposed to move the mediation forces from Commerce to the Justice Department. When Congress did not oppose the reorganization, the transfer became law. Soon CRS’s mediating role became altered by government officials shaken by the urban rebellions, particularly in Detroit and Newark. Joseph Califano, an assistant to President Johnson in 1967, told the Senate Committee on Governmental Intelligence Activities that these insurrections were a “shattering experience” for the Justice Department and the White House. The White House insisted that there must be an effective way to gather information to predict these insurrections. Attorney General Ramsey Clark responded by ordering Assistant Attorney General John Doar to review how the Justice Department maintained and collected information “about organizations and individuals who may or may not be a force to be taken into account in evaluating the causes of civil disorder in urban areas.” Doar concluded that a new | intelligence clearinghouse was required.

In December, 1967, the Justice Department’s Inter- 6 Division Intelligence Unit (IDIU) was organized according to Doar’s recommendation. The FBI and other divisions of the Justice Department — including the Community Relations Service — were to operate “a single intelligence unit to analyze the FBI information we receive about certain persons and groups who make the urban ghetto their base of operations.” Doar’s recommendation suggested that the CRS “funnel information to this unit.” He acknowledged that CRS risked losing “its credibility with people in the ghetto” by becoming an intelligence-gathering operation. Yet when the IDIU began, it was placed under the supervision of a Committee composed of the director of the Community Relations Service (then Ben Holman) and the Assistant Attorneys General in charge of the Civil Rights, Criminal and Internal Security Divisions.

CRS’ current director is Gilbert Pompa, a Mexican- American who had previously served as assistant city attorney in San Antonio and assistant district attorney of Bexar County. Pompa took his prosecuting and detective skills to the CRS, and was appointed associate director in 1970. He rose to deputy director in 1976 and finally became director in 1977. Few people know the agency better than Pompa; he insists that he has no knowledge of CRS or its previous directors, Roger Wilkins and Ben Holman, ever participating in intelligence gathering. Speaking about Roger Wilkins, Pompa adds, “Roger is black and certainly his sensitivity as I know it and knew it then would not lead me to believe or conclude that Roger would ever be a part of any intelligence operation, and certainly the people in the agency including myself would never have been a part of any intelligence-gathering operation.”

But Pompa does admit, “It becomes necessary from time to time to share information in a preventive sense [with the FBI and intelligence agencies]. For example, I was director of operations during the occupation of Wounded Knee, where it became necessary to dispute assessments from other elements of the Department. You know, the FBI might conclude that the Indians were armed in such a way that it would require, you know, better types of weaponry to respond in the event they had serious problems. It became incumbent upon people like myself to dispute that.”

Pompa doesn’t think telling the FBI exactly what kinds of weapons the Native Americans had in their possession performed an intelligence function for the FBI. “That was merely setting the record straight for the purpose of preventing an overreaction to an already serious situation,” he says.

Walking the thin line between “sharing information” and “gathering intelligence” has become a refined skill for CRS agents. In cases of marches or rallies, this often means calling activists known to the CRS and asking them if they are going to participate. The experience of receiving a sudden phone call from an official of some mysterious government agency can be quite chilling — an effect which CRS agents deny they exploit.

Atlanta-based CRS conciliator Robert Ensley freely admits that he called Southern Christian Leadership Conference organizer Golden Frinks just days before the Communist Workers Party’s funeral march in Greensboro, North Carolina, on November 11, 1979. He says he wanted to see if Frinks intended to participate in the demonstration and bring SCLC members from South Carolina. “I called Golden. And it’s only because when you call people you know to see if they’re coming, you’ve already established contact with them. You don’t call them to discourage them from coming. You only call them because you feel comfortable in knowing that they’re there and that you have worked with them before and you know the methods they will employ and what they will do and normally what they will not do. And that is the only reason why you do it, but not for any intelligence purposes. You don’t call them to persuade them not to come.”

However, some people canvassed by police departments, state police, the Justice Department’s CRS, the FBI and the North Carolina Human Relations Council said they did feel intimidated by what seemed to them an intelligencegathering operation. Carrie Graves, a Charlotte activist, got a call from an employee of the Charlotte Police Department asking if she planned to go to the CWP funeral march. This was a part of the “contingency planning” — finding out who was coming — which the CRS had convinced the Greensboro Police Department was necessary. Mrs. Graves says she was not frightened, but she did not attend the march.

This procedure of determining who will attend demonstrations was established as one of the functions of the previously mentioned IDIU, which was later renamed the Civil Disturbance Unit (CDU). Pompa says he doesn’t remember when the CDU has met, although the CRS director sits on the CDU board. Whether the CRS has ongoing intelligence connections with the FBI and other Justice Department divisions isn’t clear, but it is clear that the CRS does gather “information” or “intelligence,” an investigative function which runs directly counter to its original mandate and limitations. And it’s becoming increasingly clear that the information the CRS gathers does not support the legal rights and legitimate struggles of human-rights activists. On the contrary, the agency has become a primary force in squelching the minority rights it was created to protect.

Community Relations Service agents generally come into a community polarized over an issue, where a strong likelihood of physical confrontation exists. The agency does not need an invitation from activists on one side or the other to enter a community. But in Byhalia, Mississippi, CRS agents Robert Ensley and Marge Curet were invited to come in by State Senator George Yarborough and the local white merchants who had been successfully boycotted by the town’s blacks, organized by the United League of Mississippi (see page 73).

The boycott began following the June, 1974, death of Butler Young, a 21-year-old black shot to death while in the custody of three county law enforcement officers. Two predominantly white grand juries refused to indict the officers, who claimed they shot Young when he tried to escape. Beyond demands to prosecute the officers, the list of grievances grew to include increased hiring of blacks at the U.S. Post Office and the replacement of two white city councilmen with two blacks. The white merchants refused to budge. The boycott was set. At the time when the CRS team entered Byhalia, several stores had gone broke and several white merchants had filed an unsuccessful lawsuit against the boycott.

COINTELPRO Spies

Covert intervention in the legal activities of U.S. citizens is nothing new for the U.S. Justice Department. The FBI’s counterintelligence program, or COINTELPRO, was the best known of these secret intelligence and disruptive operations. COINTELPRO began officially in 1956 to monitor the Communist Party, USA. But its targets were soon expanded until the operation was dissolved around 1972. The following description of the program is excerpted from the April 26, 1976, “Final Report of the Senate Select Committee To Study Governmental Operations With Respect to Intelligence Activities.”

From 1956 until 1960, the COINTELPRO program was primarily aimed at the Communist Party organization. But, in March, 1960, participating FBI field offices were directed to make efforts to prevent Communist “infiltration” of “legitimate mass organizations, such as Parent-Teacher Associations, civil organizations and racial and religious groups.” The initial technique was to notify a leader of the organization, often by “anonymous communications,” about the alleged Communist in its midst. In some cases, both the Communist and the infiltrated organization were targeted.

This marked the beginning of the progression from targeting Communist Party members, to those allegedly under Communist “influence,” to persons taking positions supported by the Communists. For example, in 1964 targets under the Communist Party COINTELPRO label included a group with some Communist participants urging increased employment of minorities and a non-Communist group in opposition to the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

The FBI’s initiation of COINTELPRO operations against the Ku Klux Klan, “Black Nationalists” and the “New Left” brought to bear upon a wide range of domestic groups the techniques previously developed to combat Communists and persons who happened to associate with them.

The start of each program coincided with significant national events. The Klan program followed the widely publicized disappearance in 1964 of three civil-rights workers in Mississippi. The “Black Nationalist” program was authorized in the aftermath of the Newark and Detroit riots in 1967. The “New Left” program developed shortly after student disruption of the Columbia University campus in the spring of 1968. While the initiating memoranda approved by Director Hoover do not refer to these specific events, it is clear that they shaped the context for the Bureau’s decisions.

These programs were not directed at obtaining evidence for use in possible criminal prosecutions arising out of those events. Rather, they were secret programs — “under no circumstances” to be “made known outside the Bureau” — which used unlawful or improper acts to “disrupt” or “neutralize” the activities of groups and individuals targeted on the basis of imprecise criteria.

The stated strategy of the “Black Nationalist” COINTELPRO instituted in 1967 was “to expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit or otherwise neutralize” such groups and their “leadership, spokesmen, members and supporters.” The larger objectives were to “counter” their “propensity for violence” and to “frustrate” their efforts to “consolidate their forces” or to “recruit new or youthful adherents.” Field officers were instructed to exploit conflicts within and between groups; to use news media contacts to ridicule and otherwise discredit groups; to prevent “rabble rousers” from spreading their “philosophy” publicly; and to gather information on the “unsavory backgrounds” of group leaders.

The United League and most of Byhalia’s black citizens opposed bringing in Ensley and Curet to mediate the dispute. Their suspicions of the pair proved well-founded, as the CRS agents proceeded to collaborate with the white merchants and white politicians in a series of shady manipulations of the law to try to force the demise of the boycott. Ensley and Curet held several high-level meetings with representatives of the white merchants, including one session in the office of then-Governor William Waller. During this session, held on January 31, 1975, Senator Yarborough outlined for the group (which included the state attorney general, the director of the Mississippi Highway Commission and Robert Moore, the mayor of Byhalia) a detailed strategy for ousting the United League and ending the boycott.

Marge Curet’s confidential CRS report, dated February 4, outlined the planned attack. First, citizens who CRS and the white merchants alleged were being threatened or intimidated from shopping in the boycotted stores would be aided to shop there without reprisals. State investigators would be called in to record CRS encouraged testimony that the United League was using illegal methods to enforce the boycott. And highway patrolmen would be called in for a show of force. In another part of her memo, Curet describes how Senator Yarborough made a phone call to federal judge Omar Smith and obtained his inside, and potentially illegal, advice about what kind of injunction might be filed to halt the boycott.

Asked if the CRS didn’t seem to be in a precarious position as a meddler rather than a mediator in the governor’s office, director Pompa replied:

It does, but you’ve got to understand that we probably were not privileged to what was being done if that was in fact done. We don t know what either of the two sides is doing outside of what we know when we’re meeting with them. So you know, we were meeting, we were also meeting with members of the United League at the same time, you know, to try to see if there was some kind of resolution that could be worked out.

The United League responded to the CRS’s series of meetings with merchants and government officials with a lawsuit against Ensley, Curet, the town of Byhalia, the FBI and several agents of the state of Mississippi. The lawsuit charged that CRS agents attempted “to coerce and intimidate . . . members of the League and black citizens of Byhalia into breaking the boycott.” In court testimony as well as interviews with reporters, director Pompa and agent Ensley denied the charges made by the United League. The suit was finally resolved in an out-of-court settlement in which neither side could claim a clear victory.

CRS intervention in communities is by no means limited to frustrating activists’ organizing attempts. Most of the agency’s time is devoted to police, court and school disputes. Prison protests form an increasing part of the agency’s case load.

In June, 1975, inmates at the Women’s Prison in Raleigh, North Carolina, went on strike. After three days of protest, including a work stoppage and a refusal by the inmates to return to their dormitory, all of the parties — corrections management, inmates and outside supporting organizations — met to consider a resolution of their grievances. The negotiations were going well.

At this juncture, enter CRS agents Ensley and Earnie Jones, to “mediate.”

One central figure, Larry Little, then coordinator for the Black Panther Party in Winston-Salem, had been actively involved in the negotiations and saw the CRS team simply as meddlers:

In the height of the struggle to get some people to listen to real basic simple human requests, two individuals who I remember as salt and pepper [Ensley is black and Jones is white], who were members of the Community Relations Service of the Justice Department, came in, supposedly expressing a concern for what we were doing, and wanting to know if they could in any way be of assistance to the people protesting the conditions.

Their offer to help was met with skepticism because people in the Movement have had reason to be skeptical of anything coming out of the Justice Department, especially considering the types of dirty tricks that were played on us — outright lies, things done to imprison people in the Movement and frame people, by the FBI during its infamous COINTELPRO stage.

At one point the outside groups demanded that prison officials agree to five demands, and that they acknowledge in writing certain changes in work assignments, new safety procedures in the laundry rooms and a promise to upgrade the prison health care system. Ensley and Jones came back with the agreement typewritten on prison stationery but not signed by prison administrators. The demands were sent back for signatures, and management refused.

Following this deceptive show of willingness to “negotiate,” prison officials suddenly took the offensive. At a press conference, they accused the inmates of being unreasonable; the talks were off. Two hundred riot-armed male guards were brought in to subdue the women and to forcibly break the strike. This accomplished, the progress made toward resolving the problems went down the drain. Almost 100 inmates were loaded on prison buses and held in isolation about 150 miles away. Some were without adequate medical care, and none had access to the press or to their families. Months later, when the inmates were returned to Women’s Prison, 36 of them were held in solitary confinement in a dreary cell block. Inmates and supporters filed a lawsuit to obtain release from solitary confinement, but the petition withered and died in the federal courts. (For more on the strike, see interview with Nzinga Njeri in “Still Life: Inside Southern Prisons,” Southern Exposure, Volume VI, No. 4.)

While all of these things were happening, the CRS agents did not offer to mediate on behalf of the inmates.

Ensley recalls the breakdown in the talks, but his recollection differs from Little’s. Ensley recollects that the agreement was all worked out. But jealousies, says Ensley, between Larry Little and Reverend Leon White (a commissioner of the North Carolina Inmate Grievance Commission) caused the alleged agreement to fall apart.

“We were prepared to bring one of our mediators from our New York office to sit down and come to some agreement as to what would be put on paper about conditions at the prison and what the officials would do and what the inmates would do,” recalls Ensley, implying that nothing had been written down. But he contradicts this statement later in the interview by saying that the agreement was written and signed by the parties, but that the alleged jealousies subverted a settlement.

Little and White both deny that any rivalries on their part made the effort fail. Little concludes that the breakdown was purposeful:

I don’t think there is an appreciable difference in the CRS officers now and the FBI.... Very frankly, they’ve just moved into a more sophisticated way or more underhanded way of doing things. It reminds me of just another smoother version of COINTELPRO. They come in like they’re legitimately concerned but are designed just to get people going around in circles and going nowhere.

Veteran activist Anne Braden recalls the fall of 1975 in Louisville, Kentucky, as a time of “real community tension.” Cross-county busing opponents had developed a mass movement. Antibusing rallies attracted as many as 10,000 people. Merchants who did not place anti-busing signs in their windows received threats that their windows would be broken.

There was also activity among groups supporting desegregation and busing, but pro-busing forces faced great opposition. “There was a terrible atmosphere of fear that gripped people that had not been present for many years,” says Anne Braden. “People were afraid to speak out, and if they did speak out they were threatened.”

One pro-busing group, Progress in Education (PIE), was formed mainly by self-avowed radicals to organize support for school desegregation. PIE organizers planned a rally and march to the Jefferson County Courthouse. But there was tremendous community pressure against the demonstration. Adding to that pressure were the activities of CRS agent Robert Ensley. This time Ensley paid visits to potential PIE supporters and rally speakers.

“It would be hard to prove,” says Braden, “but my feeling is that Ensley was telling people they should not associate with people who had the reputations of being radicals. The net result was that he [Ensley] was actively undermining the only opposition in sight to the Klan and the right wing in Louisville.”

In a pattern similar to the one in Greensboro five years later, several PIE supporters and rally speakers began backing out following Ensley’s visits in the community. On this occasion, however, the rally succeeded in spite of Ensley and the CRS. It attracted a surprising 1,000 people and was considered very effective. Says Anne Braden: “The significance of that rally and march was to break through the fear that held people captive.”

Recently asked if he had discouraged people from participating in the Louisville march and rally, Ensley responded, “That’s a damn lie. How well do you know Anne Braden? What do you know about her past in Birmingham and Louisville?”

He didn’t stop there. Continuing, he cautioned, “You look back at Anne Braden, her husband, her daughter, and it goes back a number of years. Everybody in the world knows Anne Braden.” He then gave the name of a Louisville woman who could fill in the details. Despite his claim that he did not spread rumors about march leaders, Ensley subtly got his message — red-baiting — across, casting doubt on Braden’s credibility without addressing the question of what he did in Louisville.

How does the Community Relations Service continue these operations against the interests of the communities it enters? When tensions are strained, and conflicts volatile, a supposedly neutral party can often come in proposing to settle the dispute. CRS’s approach is to obtain a consensus of community leadership interested in avoiding confrontation. Pompa describes how CRS arrives at a consensus, explaining the strategy Ensley and the CRS team used in the Louisville desegregation dispute.

“What frequently happens in situations like this is . . . we might be working with a particular group that has been identified as the leadership group by a consensus of the community as the group to work through. We latch onto that group and we begin to work with them and try to bring them together with the school administration and the court and everybody else.”

To the exclusion of other activist groups in a community, CRS frequently “latches onto” the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and cooperates with this civilrights group to resolve confrontations. Ensley says the SCLC is used frequently because CRS is familiar with the group, can predict what actions they will take and has developed a high level of trust with them. Reverend Fred Taylor, SCLC director of chapters and affiliates, says that CRS is successful in many situations when “they talk with white folks, talk to us and try to negotiate the differences.” Helping SCLC obtain march permits, and serving as middle men to sometimes hostile local law enforcement officers is often done. But Taylor says the CRS agents aren’t invited. “They just show up.”

Even though the agents promote the organization as the “leadership group,” SCLC organizers remain cautious when dealing with the agency. Taylor says he trusts CRS agents, but with reservations: “What I’m going to do is above board anyway. You know I ain’t got nothing to hide. ... I mean in a sense I trust them. Let me put it like this. I wouldn’t invite the folk from Justice Department to sit in on a meeting of the Movement. But whatever we decide to do in terms of direct action, I trust them to tell them what our public activity is going to be. Where we’re going, what time we are going to start, and what we will need in terms of getting to the point where we are going. I trust them to that extent, but at the same time I realize they work for Uncle Sam. I also realize that Uncle Sam does not have our best interest at heart.”

In case after case, we have found that the CRS operates to undermine the unity and effectiveness of people trying to combat the racist abuses of our society. There are many unanswered questions about CRS’s role in subverting the response to the Klan massacre in Greensboro. We cannot be certain of the exact role the CRS played in events leading up to the aborted November 18 march and rally, but the covert operation strongly resembles the pattern of CRS-FBI activities of the late 1960s and ’70s which a Senate Comittee recommended legislation to prevent in 1976. Like COINTELPRO agents, Robert Ensley and his CRS colleagues deal routinely in halftruths, rumor mongering, red-baiting and innuendo. They may say they walk the fine line between legitimate information-gathering and illegal spying on the lawful activities of American citizens — but our investigation calls into question their mastery of that distinction.

Our research indicates the CRS’s presence in Greensboro was less visible after the aborted November 18, 1979 march. The next mass demonstration called to protest the Klan grew out a series of meetings in Atlanta. Calling itself the February 2nd Mobilization, a broad range of 150 organizations — from the United Methodist Women’s Division to the Communist Labor Party — chose that date to rally in Greensboro to protest the Klan and to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the birth of the student sit-ins.* Again black ministers in Greensboro shied away from joining the coalition, and the tensions between the obviously disparate groups remained open to manipulation by forces opposed to the march. Organizers for the February 2nd Mobilization did their best to control rumors, and in the end succeeded against great odds: 7,000 black and white students, church people, radicals and community residents did march together peacefully on that cold Saturday afternoon.

During the weeks preceding the march, CRS agents kept a low profile, perhaps because Lynn Wells and other rally organizers were increasingly vocal in their criticism of the agency’s actions in the city.** Nevertheless, CRS continued to spread divisive rumors about the people and organizations involved in the February 2nd rally. Once again, Robert Ensley appeared to be the man at the helm. During a four-hour interview in Atlanta on January 8, 1980, Ensley’s phone rang repeatedly, with questions about what Ensley throught was going on in Greensboro at the time. One call in particular confirmed what many people had already suspected: Ensley was actively spreading rumors designed to chill support for the upcoming march. The caller was not identified, but Ensley’s part of this phone call was recorded:

“Hello, I’m doing fine.” He listens intently, taking notes on his pad, and responds, “Um hum, um hum.” Finally, “Well, this is about as much as we have heard. Exactly what the SCLC has more or less determined is that they would not participate. The NAACP also.”

While the SCLC had indeed expressed some doubts about the march, they were mainly concerned about the perceived lack of support from Greensboro ministers. And at the time of the phone call, the organization was in the process of organizing a meeting to talk things over with the ministers. SCLC remained a co-sponsor of the February 2nd Mobil- ization and participated fully. Moreover, contrary to the “information” Ensley had handed out, the Greensboro branch of the NAACP had, in fact, endorsed the February 2 action.

This incident might conceivably appear to have been an innocuous mistake, except for one very striking set of coincidences. On the same day that Ensley answered this phone call, two television stations broadcast the statement that the SCLC and the NAACP had pulled out of the march. Steve Leeolou — a reporter at WTVD in Durham, North Carolina — said he got his information from a high-level official in Greensboro’s city hall. He describes this official as a “good source” who had always proven accurate before. The station later corrected this misinformation, but the damage was already done. Once again, Ensley had succeeded in planting seeds of mistrust and division among the various allies working together for a meaningful response to the menace of the Klan and the racist right-wing.

Ironically, the weeks before the February 2 march in Greensboro provided not one but several prime opportunities for the CRS to act on its original mandate: to mediate in a racially troubled community, in order to protect the rights of minorities and advance the cause of civil rights. Significantly, the CRS did not even ask to mediate the growing disputes over a parade permit, lease of the municipal coliseum and proposed repressive changes in the city’s parade permit. Greensboro’s City Hall, the city and state police, and the State Bureau of Investigation were all clearly — and publicly — involved in efforts to obstruct the people’s rights to peaceful assembly and free speech; yet Ensley and his cohorts elected to remain silent on these issues and thus mutely to affirm the offenses.

Congress did not intend for the Community Relations Service to serve as an intelligence operation aimed against the civil-rights movement. In fact, the agency’s original mandate was quite the opposite — to aid the civil-rights cause, which implies fighting the Ku Klux Klan. As we have seen, CRS has engaged in intelligence-gathering activities far beyond its legitimate purpose and has created an intelligence network that its own agents now boast is more extensive than any other agency’s. “We know who the real leaders are as opposed to the announced leaders,” Ensley claims. “We know when we go into the most rural area who to contact, who to see if there is any given problem or situation.”

How does the CRS know all this? Does it keep files? Does it share files with other intelligence agencies? Agent Ensley and director Pompa both deny the existence of CRS files on individuals. But the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence documented that at least during the early 1970s CRS director Ben Holman was involved in efforts to gather information on the legal activities of many Americans. We also know from our research that the spider web of city, county and state “human relations councils” forms an essential part of the CRS operation — both the gathering of intelligence and the dispensing of rumors and threats. Much of the leg work was done for Ensley and his cohorts by these sister agencies — as we saw in the Greensboro and Mississippi interventions — and many of the local contacts are made on this level. The exact relationship between CRS and various local, state and federal agencies remains unclear, and the degree to which they conspire to thwart legal actions of citizens in the interest of maintaining a tightly controlled “civic order” must be further examined.

A full-scale investigation of the CRS and its intelligence network is obviously long overdue. The agency’s involvement in illegal activities, and its possible role as a replacement for the FBI’s COINTELPRO in conducting outlawed intelligence functions must be scrutinized; its purposes must be clarified or the agency dissolved. The CRS’s exact role in Greensboro in covering up mistakes, mismanagement or worse abuses by city and police authorities also demands exposure — as well as the agency’s possible violations of the civil rights of the very organizations it was created to protect. Only after these investigations are completed will the cloud left by CRS involvement in the Greensboro killings be lifted.

* On February 1, 1960, four students from A&T University sat in at the segregated lunch counter at Woolworth’s, launching a wave of student sit-ins that led to the founding of SNCC (see Southern Exposure, Volume VI, No. 3, p. 78).

** CRS’s regional director in Atlanta, Ozell Sutton, became so concerned about these allegations that he paid a visit in late December to SCLC president Dr. Joseph Lowery to deny Wells’ charges, which had been published in newspapers.

Tags

Pat Bryant

Pat Bryant is a writer, community organizer, and director of Gulf Coast Tenant Organization, which operates in poor African American communities in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. He is a board member of SOC and the Institute for Southern Studies in Durham, NC.

Pat Bryant is an editor of Southern Exposure and field organizer for the Southeast Project on Human Needs and Peace. (1982)