My Life with Sports

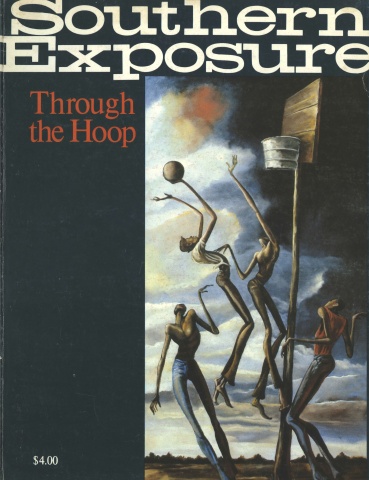

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-gay slurs.

A boy dances in the feverish shade under the trees. He glistens as he turns and turns and turns. Beethoven blares from the house. The boy wears baggy shorts with an elastic waistband. It’s 1955. He’s about to take a long, painful journey from which he’s still returning.

Home movie: blue-shadowed children play on glaring sand. Susan frolics with seaweed on her head, Becky smiles uneasy smile of youngest, Nancy looks up from sand castle, scowls, speaks, Chris jumps around in surf, I hold up a shell. Angel wing, scallop, conch, baby’s ear, coral, cockle.

I wandered many hours on Long Beach those summers, looking, looking. Bags full of shells. In the dark, heat lightning flashed and waves rumbled and hissed. “Shrimp boats are a-comin’ their sails are in sight, shrimp boats are a-comin’ there’s dancin’ tonight,” I sang bravely as I walked at night on the squeaking sand. Riding waves once, suddenly there was nothing under my feet. Thrashing, screaming, going under. My brother pulled me in.

In Greensboro in the evening suffused with honeysuckle and clematis we played croquet. When it got too dark to see the balls we tossed sticks high as we could and watched bats streak across the dim sky. When it got too dark for that we watched the lightning bugs blink and slowly rise. I lived comfortably in my body then.

Daddy would take us bowling. In the event that I knocked over any pins, a colored man appeared from nowhere and set them back up.

In the woods — the climbing tree, the owl tree, the hideout under the eleagnus below the ballfield, the big hole in the base of a tulip poplar, full of black water that wiggled. Forever, on autumn afternoons, I journeyed from island to island in that sea of sibilant leaves. Now I reach up easily to touch the dogwood branches where I used to climb, fearless and dizzy, and sit until called for supper.

Before play became sports, before my friends and I graduated to the sexual strife of our adolescent elders, th ere was sling-the-statue and mother-may-I in the backyard, red-light and roller-bat. I painted and drew and sculpted exuberantly. We went fishing out at Cousin Lizzie’s. Richard Taliaferro and I roller-skated to school, to the great chagrin of Mrs. Sears, policelady. “Stop the cars!” we'd holler, careening down Dellwood and past her station at Cornwallis, unable to brake. I dawdled in the locker room at Lindley Park Pool to watch the naked bodies of the older boys and the men. Eventually, they closed the pool to keep the Negroes out.

Then, one summer, I went to Y camp. I thought I’d make friends and do arts and crafts and play in the lake. Instead, I struggled to be promoted from Guppy to Minnow, or Minnow to Guppy, and wasn’t. I became afraid of the water. On carnival day, in a sweltering tent, a handsome counselor brandished a jockstrap, which was the punch line to a joke I didn’t understand. By the campfire one night, the boy who was ‘It’ never guessed right and ended stripped of all but the paper bag over his head. Then in the dwindling light, we all sang The Old Rugged Cross. In the Chapel in the Woods, we learned about the Lake of Fire and the Seven Trumpets. On Parents’ Day I fled to the toilet labeled “His’n” and wept.

A snapshot: I wear a somber dress that hangs limply around my ankles. Navy blue, at best, with tiny dots. Probably from Miss Effie, grandmother, Methodist preacher’s wife. Heavy black heels, small black hat with net, menacing pocketbook, serious face. I am seven or eight.

The old footlocker filled with mildewed clothing from female relatives was a magic place, just as the backyard ballfield was for my brother. I chugged around in high heels as easily as sneakers. Pants and shirts, and a suit on Sunday, were uniforms. Dress-ups were expression and amplification. But then on the playground at school someone told me I ran like a girl. Douglas Banner peed in the dress-up box, and one afternoon when I saw some friends coming up the driveway, I ran to my room, slammed the door, and tore off my costume.

Home movie, 1956: On the terrace behind the house, boys eat hotdogs. My birthday. Andy Steele, Jimmy Morris, Ed Moore, Wesley Graves, others. They would rather play baseball than run relay races, but it’s my party and the testing is only about to begin. Somebody gives me a baseball bat.

The summer of ’58, I painted my violin case silver and went to the String Institute over at the Women’s College. Ed, Wesley, Jimmy and Andy went off to sports camp at the coast. I had a vague image of Episcopalians in sailboats. That was the year I threw up on home plate and walked home from school crying.

Saturday morning recently, at the farmer’s market in the dreary armory. A young man in white work pants has bought an extravagant armful of flowers. I smile. He smiles back. May Day mornings in the Irving Park Elementary School Auditorium. Peonies, iris, sweet Williams, pansies, and roses in Mason jars and tin cans spread across the waxed wood floor. Garden club ladies arranged bouquets for the Sixth Grade girls. I waited in the cool, fragrant half-light, in case they might need some help. They never did.

The young man at the farmers’ market and I each searched for the very spot in the outfield where balls would never land and where you wouldn’t be noticed when the teams changed. “Throw it! Throw it!” I’d run as fast as I could with the ball — “Throw it!” — and then heave it (Oh lord do I look right?) and it would wobble in toward the diamond. I no longer danced under the trees.

My first role with the Recreation Department’s children’s theatre was Tweedledum, followed by many princes and kings, since the other boys were even sissier than I. On a float in the Christmas parade, I had to kiss Brenda Kay Huffines’ hand all the way down Greene Street to the old train station, and back up Elm. Schoolmates jeered.

In 1959, Junior High hit. I wonder sometimes what would have happened if I had loosened my grip. Then, annihilation seemed the only alternative to wrestling against a brutal, faceless future. What if my fears had floored me? As it was, I was 20 years breaking the hold, and only then with the help of another man’s strong and gentle arm.

I made A’s in Social Studies because I couldn’t throw the football to where Mr. Thompson started measuring from in the Phys. Ed. proficiency test. I had to win the science fair or Mr. Griffin would smirk at my unmanly lapses. Every time I missed a free throw I’d shake my head in exasperation or, in later years, shrug comically. Both responses were faked, and tore into my muscle and bone. I wanted no part of their sports, neither beating nor getting beat. Seemingly, I withstood the stomach aches, the bad dreams, the anxiety waiting my turn at bat. But my capacity to feel was going. The neurons wore out, and I went numb. In English class, Mrs. Crisp assigned an essay on a Familiar Emotion; she was startled by mine on Hate.

I was elected school president, won awards for service, and prizes for musical, artistic and theatrical accomplishments, and appeared quite popular. My first week in Senior High, I waited and waited for an invitation to join the Junior Civitans or the Key Club, but of course it never came and I was officially out of the running. They knew I was not going to fulfill the destiny of my class and sex. I would never again eat hotdogs with Wesley, Andy, Jimmy or Ed, who now wore service club jackets, played football, basketball, or at least tennis, and dated.

In North Carolina, sports attain the numinous, and religion gets right down there on the gridiron and the court. Preachers lard their sermons .with basketball jokes, and when they want to deliver a real punch, refer to “muscular Christianity.” “Christian athletes” huddle in prayer before football games, and with bull-necks bulging at collars and ties, they speak to youth groups. I sat through pep rallies with a few stone-faced friends, and went to none of the games. I wore neither a Duke nor a Carolina button. One Sunday school teacher, a Carolina man, threw me out of his class for talking about conscientious objection.

Music and theatre provided refuge for the life-force that had been trampled by physical education. Breathing deep, I swung through Beethoven quartets and Brahms symphonies. I went off to Terry Sanford’s Governor’s School the summer of my sophomore year where I, too, was cruel to my ballet-dancing roommate (forgive me, David, brother). My second summer, I lay in bed one night and listened in horror as my roommate Clyde, a baseball star from Shelby, debated in the hall with his friends whether I was queer or not. “Yeah. Well, he’s got a girlfriend.” Five years later, she would be the first person I told. But music, too, could be made competitive. I was chosen concertmaster of the All-State Orchestra, which meant I’d have to play a solo. I was terrified. Couldn’t I be second chair instead? (“Throw it! Throw it!”) In the concert my bow wobbled helpless and alone. I decided against music as a career.

Michael Mandrano was from somewhere else. He had long fingernails as well, a peroxided streak, and he moved when he walked. In drama class, he talked in a high, exaggerated voice about faraway places from which he’d come, and to which he aimed to go. We snickered and led him on. When he entered the auditorium with his homeroom for assembly programs, the general racket exploded into catcalls and whistles. One day, toward the end of my senior year, the catcalls seemed to be for me. I got out just in time.

I escaped to a Quaker college in Pennsylvania. Their pacifism allowed for mandatory football and wrestling. To avoid combat, I tried managing the lacrosse team, but got confused keeping score and watching the clock and was fired. I flunked my swimming test, and for the rest of the term stood shivering with the other failures by the pool while Coach barked at us. There was nothing sensual about our quaking, bluish bodies. My libido found no quarter (Eros was an unwelcome guest in those puritanic halls), unfinished papers backed up, and I got kicked out. Last fall, 10 years later, a college classmate lay in my arms and cried about those years.

Into the maw of the draft. I feared the military as I had feared Phys. Ed. But unlike my school years, when there was no outlet for my corrosive anger, now there was the anti-war movement. Every Wednesday I stood with the other protesters outside the Federal Building in Greensboro. Once, a car loaded with young men about my age swerved around the corner, and shouts of “Hippycommiefaggot!” clawed at our silence. When the clock on the Jefferson Standard Building finally blinked from “98°” to “1:00,” Anne Deagon turned to me and said, “You’re the nicest ‘hippycommiefaggot’ I know.” I tried to laugh.

The draft board classified me 1-O; I went off to Boston for two years’ alternative service. No longer would I have to dread the orders to run, throw, fight or kill. When my C.O. job was over, the first thing to do was come out. Allan and I lay in bed after lovemaking and laughed for joy.

The literature of sports overlooks one important character. The sissie. The traditional foil for masculine bravado, the one who saves all the others from being chosen last. How powerless boys would be without the accusation, “Faggot!” And coaches and drill sergeants. We are the taboo that enforces order, the outside that shapes inside. Outsiders. One night in the early spring a couple of years ago, Carl and I found ourselves on Franklin Street, the main drag in Chapel Hill, the night Carolina was playing the national championship game. Car horns and sharp voices tore the buzzing air. Word was that victory would see store windows smashed and the streets awash with Carolina blue paint. That we were not visibly queer was slight comfort, and we hurried to get away.

The threat of getting beat up lay just beyond the bruising jostle of football in Junior High. There seemed to be nowhere between combat and weakness. Recently, I went to a conference in Norfolk for gay men and lesbians from across the South. Toward the end of a workshop on Play for Men, a friend said he needed to explore further. He pushed his fists together and frowned. So, locked together in threes first, and then as nine, we writhed on the floor — nine men, black and white, grappling to wrest our bodies and spirits from exile. Afterwards, we lay in a sweaty tangle, still and breathing. And then we all hugged each other.

I can dance again now, easy and graceful and strong. Sometimes it’s folk-dancing with friends, leaving behind the men’s and women’s parts, dancing wherever we choose. And then sometimes I dance alone.

Out in the barn, shafts of sun slant down from the high windows. A man sways in the quiet light. He turns and turns and turns. He opens his eyes and takes a step. I am almost home.

Tags

Allan Troxler

The author lives and works in Durham, North Carolina. His interview with Robert Lynch, entitled “Rabbit," appeared in the Fall 1988 issue of Southern Exposure. (1988)

Allan Troxler is a dancer and artist in Durham, North Carolina. (1988)

Allan Troxler is a staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1979)