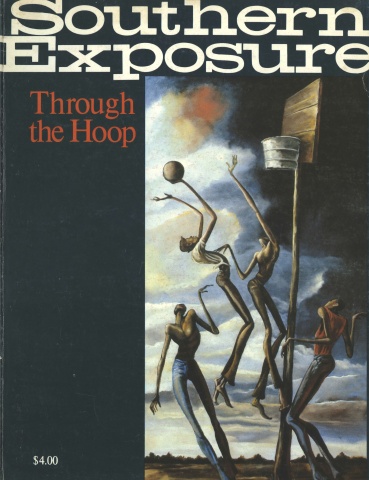

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

“Ain’t that Jackie Robinson?”

Granddaddy would ask the same question every time a black player was shown during the television baseball game of the week. And if he had forgotten his glasses again or if the television’s picture was a bit fuzzy, he would ask it for the white players too. Granddaddy asked the question long after Robinson, the Dodger second baseman and first black player in the big leagues, had retired from baseball and was going blind.

It was the same with almost all the old black men who came to watch us play in the youth league. As we raised clouds of dust on fields scraped out of the red Georgia clay or tore up the turf of someone’s freshly mowed pasture pretending we were the men we wanted to be, the men we were likely to become stood on the sidelines in their work-stained clothes. Whenever one of us made a good play in the field, the old men would whoop and holler, and invariably someone would yell, “Just like Jackie Robinson!” It didn’t matter that the player being praised was playing a position Jackie Robinson never played. The cry would build into a chorus and all the old men would be yelling, “Yes suh! Just like ol’ Jackie Robinson!”

Among ourselves — the young players — we tried to be present-day heroes, men like Willie Mays, Elston Howard, Ernie Banks, Al Downing, Roberto Clemente, Bob Gibson and Maury Wills. But to the old men, who had been robbed of the chance for such idols in their childhoods, baseball began and lived through one person: Jackie Robinson. He was the game incarnate. All the old men worshiped him.

All except Big Granddaddy William, that is. He was Granddaddy’s daddy, and a mild rage would come over him at the mention of Jackie Robinson. His rage was inevitably followed by his baseball story. It was Big Granddaddy William’s best story; like all the rest, it happened so long ago that there was no one around old enough to have been there and dispute the facts. And no one could say whether Big Granddaddy really was old enough to have done all the things he claimed because no one knew how old he was.

“Jackie Robinson. Jackie Robinson,” he always would say, his anger sharpening his memory for the story. “Why is all I ever hear is Jackie Robinson?” “He broke the color line in baseball, Big Granddaddy,” I would say, playing the straight man. This was before the old Negro League and the exploits of men like Cool Papa Bell, Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Sam Jethroe and Buck Leonard had been resurrected from the obscurity of neglected black history, so I would add: “He was the first colored man to play professional baseball.”

“No he weren’t,” Big Granddaddy would say indignantly. “I remember back in eighteen and sixty-four at Fort Po’laski at Savannah. We played baseball there and it sho’ was professional.”

His story begun, he would lean back in his rocking chair in the evening coolness of the big front porch. I would sit Indian-style at his feet and watch as his still-nimble fingers rolled a cigarette from some of his Prince Albert Tobacco. Big Granddaddy William was a small man, and his hands looked delicate as they handled the cigarette. They were boney and veined, and the skin on them was like wet wax paper wrapped around raw chicken.

While he prepared to smoke, I pictured Fort Pulaski, the scene of his story. There really is such a place; my class went there on a field trip once. It sits on the marshy Georgia coast where it unsuccessfully guarded the entrance to the state’s most important port during the Civil War.

My classmates thought the place was dead, like the rest of history, and that it would have been better off buried and forgotten so they wouldn’t have to write reports on it for homework. But for me it was alive. My great-grand¬ father’s stories made it so. I could imagine him standing guard atop the parapet or marching on the parade ground with members of his all-black regiment or walking, torch in hand, through the fort’s dark storage tunnels.

But most vividly of all I could visualize the baseball game. The high wall surrounding the parade ground gave the fort the appearance of the major league stadiums I had seen on television. The pool table smoothness of the lush green grass of the parade ground was what I imagined the carefully manicured playing fields of the big leagues were like. And as I stood on top of the wall and looked down at the inside of the fort, the configuration reminded me of aerial views of major league ball parks I had seen in books.

“We was members of the 27th Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops,” Big Granddaddy would say. “At the start of the war everybody up North thought it was goin’ to be a easy fight and they wouldn’t really need no help from us colored folks to whip a bunch of upstart, backwoods rebs. But they thought that by lettin’ us have some colored regiments we would learn us some responsibility. I ’spect they also figured it would aggravate the South some too. They wouldn’t let us do much fightin’ though, mainly ’cause most of the gen’rals didn’t think we had military Fightin’ in us.

“’Bout the only time we got into battle was when the situation had done got hopeless. Then they would let us go in and Fight, and when we would get our tails naturally whipped, then them gen’rals would say to each other, ‘See, I told you they ain’t got it in ’em.’ And when by some miracle of God Almighty we went into a hopeless situation and come out with a victory of some sort, they always laid it to the inspired leadership of our commanding officer, who always happened to be white.

“But we didn’t do that much Fightin’ a-tall. Mainly we just marched. I swear I marched enough to give a mountain goat bad feet. When we wasn’t marchin’ we was just sittin’ round waitin’ for the next hopeless situation to develop. I was awful young at the time, like most of the other fellas in the regiment. Just about every one of us was too young to be in the war, but white folks didn’t have no talent a-tall for guessin’ the age of colored folks by lookin’ at ’em, so we got in all right.

“Like I say, we was all young and naturally restless. It would come up a long time between tailwhippin’s and we would be just a-fidgetin’ for somethin’ to do besides march. So we played baseball, and child, I want to tell you we played enough of it to be good. Yes suh, we even got us a reputation that spread through the Union Army.

‘“They can’t fight,’ folks started sayin’, ‘but they sho can play theyselves some baseball.’

“And I tell you, child, that I ain’t braggin’ but just statin’ the facts when I say I was one of the stars of the team. You can ask anybody,” Big Granddaddy would say, knowing full well that there was nobody to ask. “Me and another soldier name of Joshua.

“Lord, that Joshua was some kind of man. He had done the work of a full-fledged blacksmith since he was 15, and he had been big and strong enough to do it since he was 12. Good God, that man was big! And black. We used to joke with Josh and say he had done spent so much time round that blacksmith’s hearth that he had done burnt hisself to soot. He always would say it come natural that he was black as midnight in a cave.

“Joshua was one proud man. When he walked down the street he’d step aside for no man, black nor white. Folks just naturally stepped aside for him. He weren’t no bully; he just felt like he had as much right to walkin’ space as anybody else.

“That man Joshua was a sight to see playin’ some baseball, ’specially hittin’. Lord God Almighty, that man could naturally knock a baseball from here to yonder every day of the week and twice that on Sunday. Them teams what we played learnt to just get a head start on looking for the ball whenever Josh come to bat.

“I wasn’t much in size compared to Joshua. In fact, I was small compared to just about all the other fellas. But I was the second best hitter on the team next to Joshua, and didn’t nobody argue the point. I wasn’t that strong, but I used my head a lot better’ n the others when it come to hittin’ that baseball.

“You see, I had done a little taste of lumberjackin’ before I sneaked into the army. That was up in the Northwest. One of the things I learnt was the proper way to swing a axe. And that’s the way I swung that baseball bat. All the other fellas held the bat with they hands a ways apart from each other. Even Joshua did, but he was so strong that it didn’t make that much difference. I held my bat with my hands close together.

“And another thing I done was I changed up on which side of the home base I hit from. All the other players stood on the same side all the time, but I Figured that if I learnt to hit from both sides, why I’d just get half as tired from all that hittin’.

“We could naturally play ourselves some baseball, and a lot of folks heard about us. One of them folks was the Union colonel who had took charge of Fort Po’laski and who went through special trouble to have our regiment sent to his command there.

“Colonel Aldridge was his name. He was a man not much bigger’n I was back then, but he had the biggest hunger for winnin’ than anybody you ever would want to see. He was known as a hard man who drilled his troops and pushed ’em and worked ’em ’til they was ready to do nothin’ but fight and win. So we figured that we was ’bout to do more marchin’ than we ever done before.

“But when we got there the colonel hisself greeted us and he didn’t say nothin’ ’bout drillin’ and marchin’. He just said, ‘I hear you boys play some baseball. Our parade ground out there is a perfect ball yard. Why don’t you go out and practice and play some?’ That’s all he said do and that was just ’bout all we did for a solid week.

“Whenever we was out there Colonel Aldridge would be standin’ round real watchful-like, and sometimes a sort of secret smile would come from behind his beard. In fact, everybody was watchin’ us, includin’ the Confederate prisoners of war who was allowed out in the parade grounds from time to time.

“One day, I happened to be standin’ close to where Colonel Aldridge was. He had sent for a Confederate prisoner, a sergeant. His name was Cobb and I found out he was from right here in Georgia, north of Atlanta. This Sergeant Cobb come up to Colonel Aldridge and says, ‘Y’all wanted to see me Cap’n?’ He said it real sassy-like, like he knowed perfect and well Aldridge was a colonel but he wanted to show that he didn’t have to admit it.

“Aldridge, he just let the insult pass. He says to Cobb, ‘Sergeant Cobb, you said your team would be willin’ to play another game of baseball anytime I wanted.’

“‘I reckon we’ll play for the usual stakes against any of your men you want to put up,’ Cobb says.

‘“What about these men?’ Colonel Aldridge asks, noddin’ his head toward our regiment team.

‘“I said any men you got,’ Cobb says, ‘not niggers.’

“‘These are Union soldiers,’ Aldridge says. ‘We consider ’em men.’

“‘That’s just two marks against ’em instead of one,’ Cobb says, real smart-like.

“‘Will you play ’em or won’t you?’ Aldridge says. He was gettin’ madder’n a bumblebee in a bottle.

‘“I reckon we whipped all the men you can put up, and I reckon we can whip your darkies too,’ Cobb says. And then he says, ‘Let’s make the stakes a little more innerestin’. Instead of just sayin’ the winner gets a extra supper ration for a week, let’s also say the loser goes without supper rations for a week.’

“‘That’s fine,’ Colonel Aldridge says, and he walks off.

“And so the game was set, and Lord, they was makin’ a big to-do ’bout the thing. Everybody in the fort was talkin’ ’bout it. Most fuss I ever seen over a little ol’ ball game. They decided to have it on a Saturday, the day they always invited the ladies from Savannah to come over to the fort for a evening dance. So the ladies and some of the men folk from the town was goin’ to be at the game. Child, that game was workin’ up into a natural occasion, and none of us on the team knowed why at first.

“It didn’t take long for word of why to get to us, though. We found out that this was to be the fifth game that a team from the Union army would play the rebs, and each time before the rebs had won. Colonel Aldridge had arranged the games for the fun of it, at first, but when the Union teams lost, he got madder ’n madder. The first time he put up a team from his original command. When they lost, he took it out on ’em by drillin’ and workin’ and marchin’ ’em until they practically dropped. After that he brungin teams from other Union regiments. When those lost he had ’em shipped off to duty in the area ofTennessee that was controlled by a band of rebs called Johnson’s Raiders. If we lost we likely would be gettin’ the same duty.

“Now that was particular bad news for us ’cause everybody had done heard of Johnson’s Raiders and knowed they was the meanest, toughest, most dirty-fightin’ bunch that the Confederate Army had. They wasn’t particular ’bout how they shot you as long as you got shot. They would ambush you and shoot you in the back; they would come howlin’ out of the hills and attack at the most God-awful time of night. They would even stoop to dressin’ up like women and come strollin’ towards a encampment and suddenly pull guns out from under they dresses when they got close enough. Any regiment that got sent up against ’em stood to lose a lot of good men. So we started takin’ a special interest in winnin’ that game.

“We got word that it weren’t goin’ to be no easy matter. Everybody who had seen ’em play said the rebel boys was some kind of good. That Sergeant Cobb was supposed to be the best of ’em. He was a natural terror on that field. While all the other players would always run into the bases standin’ up no matter what, this Cobb would come slidin’ in on his backside if the play was goin’ to be close. And sometime if it was goin’ to be real close he would come floppin’ in on his belly.

“That man didn’t have no limits. He drove nails through the soles of his boots so the points stuck out the bottoms. He said it was cause it made him run faster, but anybody that seen him play could tell you that weren’t the only reason. It didn’t take many basemen to be carried off the field bleedin’ before the others learnt to step aside and let the sergeant have his base.”

Just about that point in his story, Big Granddaddy William’s throat would get dry.

“Child,” he would say to me, “go look in the ice box and bring me a bottle of dope.”

“Dope” was what Big Granddaddy William and all the old folks called Coca-Cola out of a belief that it had cocaine in it. After a few sips, Big Granddaddy would rock back, belch, and go on with his story.

“It come the day of the game and there was a feelin’ in the air like the first day of 10 county fairs rolled into one. It was a cool, sunny day in the early fall. A nice breeze was blowin’ in from the sea, cornin’ over the high marsh grass to the fort. There was a lot of folks from Savannah there. Some of ’em stood back along the baselines and some stood up on top of the wall ’round the parade ground. It was a sight, what with all the ladies dressed up real fancy and each of ’em with a different color parasol held over her head.

“The first thing we done was to settle on the rules. Them rebs wanted to play that countrified ball, the kind where you can put a man out by hittin’ him with the ball if he’s off the base. But we weren’t havin’ none of that stuff. We said we was goin’ to play by civilized rules and that’s the way it was.

“Once we got started things was real tight. Them rebs wasn’t much as hitters, but they was scrappers. Our team jumped out to the lead right away, mainly by the work of Joshua and me. I would get a hit and Joshua would come up behind me and knock the ball over the wall. Them rebels had never seen nothin’ like it and the first time Joshua did it they was a big argument.

“The rebs said that since hittin’ the ball over the wall cause so much trouble, what with havin’ to go find it and all, then when it was done it ought to be a out. But Colonel Aldridge settled the argument by sayin’ that if the object of the game was to hit the ball, then you can’t penalize a man for doin’ it better’n anybody else.

“I had noticed that the wall I would be hittin’ towards if I was standin’ on my left-handed side of the home base was a lot closer than the other side. So I determined that I would hit from that side. And I be danged if I didn’t hit one over the wall. It sho did aggravate them rebs to see a little biddy thing like me knock the ball over that wall.

“Between me and Josh and what help we got from the rest of the team we would build some sizeable leads. But them rebs wouldn’t never give up and they was always peckin’ away, cornin’ back to make it tight. Every time they scored a run the reb prisoners and the folks from Savannah — even the ladies — would let out one of them ear-piercin’ rebel yells. The Union soldiers would give a cheer whenever we scored, not so much ’cause they wanted us to win, but ’cause they knowed Colonel Aldridge wanted us to win.

“It soon became apparent that this was one game that was goin’ right down to the wire. The rebs was gettin’ scrappier by the minute and was doin’ all they could to catch us. Sergeant Cobb was livin’ up to his reputation for playin’ hard and dirty. But me and Joshua kept doin’ the job.

“One time late in the game I bounced one off that wall and made it into second base. That Sergeant Cobb come trottin’ over and he says real quiet-like, ‘Nigger, next time you hit the ball you ain’t goin’ to be able to run ’round these bases.’

“I looked at him real hard and I says, ‘What you say, white man?’ I was tryin’ to sound like I wasn’t scared, but Lord knows I was.

“He says, ‘Next time you hit that ball and try to run ’round these bases you liable to get kilt along the way.’

“I says to him, ‘You try to do anything to me and Colonel Aldridge goin’ to take care of you.’ “And he gets a real wicked grin on his face and says, ‘What he goin’ to do, put us in jail?’

“I had to admit that the cracker had a point. They weren’t much could be done to ’em that weren’t already bein’ done. I was worried, real worried.

“Well, child, it come down to our last time at bat and danged if we didn’t find ourselves two runs behind. Them rebs had done scrapped back and took the lead. Our first two men at bat went out, and I could just hear Johnson’s Raiders cornin’ down at me in the middle of the night. But our next man got a hit and it was my turn at bat. I remembered what Cobb told me, and I told the other fellas.

“‘What I goin’ to do?’ I asked ’em. ‘What you mean?’ they asked me. Then they answered their own question. They says, ‘You goin’ to get up there and help win this game lessin you wants your back in the sights of Johnson’s Raiders.’

“So I found myself up there caught between two bad situations. I decided to just do my best and let the rest take care of itself. Well, child, I hit that ball and it went to the furthest part of that parade ground, straight up the center of the ball field. It was a mighty hit, and it just barely missed clearin’ the wall. It landed up there on top and stayed there. The folks standin’ on that part of the wall stepped aside and you could see the ball just sittin’ up there. I was about to run the bases when I looked up and seen three of the biggest and meanest lookin’ of them rebs. Each one of ’em was standin’ on top of a base, glarin’ at me and darin’ me to come his way. At the same time the rebel outfielders was runnin’ ’round tryin’ to climb up ladders to the wall so they could fetch that ball and throw me out.

“Well suh, I just stood there. Didn’t know what to do. The other fella had come ’round the bases and scored, but we still was one run short. I had to score to tie it up. If I didn’t run soon I’d be throwed out for sho. The fellas was yellin’, ‘Run William! Run William!’ Like it already was Johnson’s Raiders behind me and them. And Colonel Aldridge was yellin’, ‘Run you damned fool! Run!’ Like he could see another defeat sneakin’ up ’bout to grab holt to him. I just stood there lookin’ at three of the meanest lookin’ peckerwoods I ever did lay eyes on. I couldn’t do nothin’.

“All of a sudden, Joshua ran out there with the meanest look on his face that I even seen on a human bein’. He grab me up just as easy as I was a dollar sack of groceries. He carried me down to first base and that big reb saw the biggest, blackest, meanest lookin’ man he ever saw cornin’ chargin’ down on him like a angry bull, and he just stepped aside. Joshua touched me down on that base and then picked me up again. He went chargin’ down to second base. The rebel stepped aside and Joshua touched me down again. He charged down to third base and the reb looked like he wasn’t goin’ to step aside, but the look lasted for just a second. He stepped aside and Josh touched me down and then carried me on in to home base.

“There weren’t no other way I coulda made it ’round them bases and tied the score. Joshua was next up to bat. He was so riled up at what them rebs had tried to do that he knocked that ball clean away. They ain’t never found that one yet. When Josh come ’round them bases we had won. We was so happy that we wasn’t goin’ to have to face Johnson’s Raiders, not to mention not havin’ to go without supper, that we went out and tried to pick Joshua up on our shoulders. We should have knowed better. That man was too big for all of us put together to carry.

“Yes, child, that’s the way it was,’’ Big Granddaddy William would say, rocking slowly in his chair as if to ease the last of the story out of himself. “All I know is we was playin’ for our supper and for our lives and you can’t get no more professional than that. So I don’t see what is all the fuss ’bout no Jackie Robinson.”

Tags

John Head

John Head, a 28-year-old writer living in Atlanta, learned the joys of baseball on makeshift fields around his hometown of Jackson, Georgia. His short story is based on a tale related to him by his grandfather. (1979)