This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 3, "Passing Glances." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

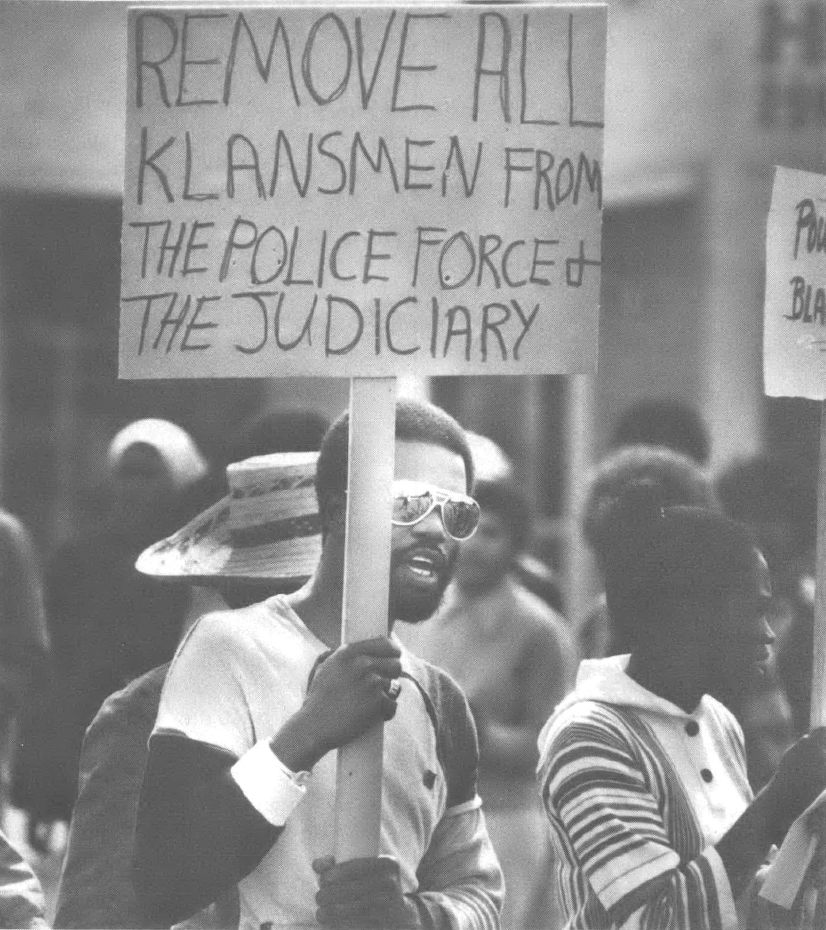

Blacks carry picket signs on Main Street in Tupelo, Mississippi, while Ku Klux Klansmen circle the area in cars and pickup trucks. A cross burns in Holly Springs, 50 miles northwest, at the church where a black protest march began one day earlier. The Tupelo city attorney tells a federal judge that his city is a “powder keg waiting to explode.” And a 17-year-old white youth drinking beer illegally in a bar tells reporters he drives through black neighborhoods yelling obscenities “to get them stirred up. ”

It is the civil rights struggle of the past, only it is happening in Mississippi in 1978.

The center for the movement is Holly Springs, the largest city and county seat of Marshall County. The town boasts antebellum mansions set in northeast Mississippi’s rolling hills and national forest. At one corner of the town square a state historical marker recalls the old cotton town’s past as a “center of social and cultural life.” Today, most of the 6,000 residents are black and — like many white residents — frustrated by high unemployment and poverty. Per capita income for Holly Springs was $2,853 in 1975, less than half the national average of $5,902. These economic frustrations, compounded with what they consider unequal treatment at the hands of the local white power structure, have led blacks to organize in local communities throughout the region for jobs and equal justice. Marches, rallies and boycotts are becoming commonplace activities, spearheaded by a relatively new civil rights organization called the United League.

Founded in 1966 by Alfred “Skip” Robinson, the United League fights its battles both in the streets and in the courtroom. According to Robinson, the League is a “priestly, militant, revolutionary organization” committed to winning employment, education and health opportunities for Mississippi blacks. It has sponsored lawsuits challenging local election laws, local officials’ use of federal funds and inaction on school desegregation matters. The complaints also include police brutality and a series of murders of blacks in which white suspects were arrested but never indicted or tried.

Until recently, the organization remained little-known outside the area. Its principal claim to fame was a boycott of Byhalia, Mississippi, a town 10 miles from Holly Springs, following the 1974 killing of a black man, Butler Young, Jr., by a part-time policeman. Two grand juries refused to return indictments against the officer, and the League, building on the momentum of protests that resulted, filed lawsuits challenging various discriminatory practices and began a boycott of downtown stores. It also initiated a lawsuit against the police officer on behalf of Young’s mother that resulted in an award of $15,000 in damages from an all-white jury. The League is now appealing that verdict because, in the words of League attorney Lewis Myers, “we think that’s too small a sum for the death of a 21-year-old man.”

The United League is not the only group on the move these days. The Hunger Coalition and Concerned Citizens Against Police Brutality are behind protests in parts of north Mississippi which the United League has not reached. Unlike traditional forces such as the NAACP or SCLC, these groups lack both fame and money. With membership costing just one dollar, the League appeals to the poorest citizens and seeks its strength from the masses, rather than from a hefty treasury. “The League is better off without a lot of money,” says Joseph Delaney, a black journalist from Oxford, Mississippi, who has been active in League affairs. “Money just means trouble.”

Indeed, the NAACP has recently been cautious pending a decision in its appeal of a $1.25 million state court judgment against it for the association’s 1968 boycott of white stores in Port Gibson, Mississippi; meanwhile, the League leaps to the forefront of such activities. “The League doesn’t have that kind of money to lose,” says Henry Boyd, Jr., secretary of the League. “Some of the blacks who once stood up and fought for justice now are complacent,” says Robinson. “They have become part of the system. We are trying to awaken black folks to this.”

This past January, the League called for the ouster of Marshall County Sheriff Kenneth Smith after a black man, James Garrett, was found hanging in Smith’s jail with hands and feet bound. Smith called Garrett’s death a suicide. Largely because of League efforts, the Marshall County Board of Supervisors held a special hearing in February in which witnesses detailed beatings in county jails. One woman said the jailer allowed a man to enter her cell and rape her. As a result of the hearing, the supervisors cut back the federal funds of Sheriff Smith.

In March, United League officials wrote the area’s US attorney, H.M. Ray, complaining about his poor track record in prosecuting civil rights violations and saying, “There is an air of hopelessness on the part of many black citizens in north Mississippi concerning the attitude or seeming attitude toward the vindication of their constitutional rights as black American citizens.” In a reply letter, Ray denied that his office failed to prosecute civil rights cases.

In April, one week before the annual pilgrimage of tourists to Holly Springs’ antebellum mansions, hundreds of blacks turned out for a League-sponsored “March for Justice.” The League has since held several more marches and has threatened to picket downtown stores unless more blacks were hired. Holly Springs merchants, mindful of the League’s success in nearby Byhalia, quickly formed a committee to try to meet the League’s demands. But by late June, the League was still unwilling to call off its protests.

Recently, Robinson has sought to spread his gospel outside of Marshall County, organizing marches in parts of Tennessee and Alabama. He has announced a July protest in Plains, Georgia. At a recent press conference in Holly Springs, Robinson declared that the League would be going “nationwide.” He already claims 50,000 members in the organization, but Robinson has a reputation for considerably inflating such figures.

The United League’s rapid success gained a boost from its recent move into Tupelo, a town of 21,000 that serves as the retail trading center for the northeast part of Mississippi and that is widely known as the birthplace of Elvis Presley. The Tennessee Valley Authority provides cheap electricity for residents and industries, and Tupelo’s low-wage, non-unionized labor force has grown rapidly in recent years. The town’s per capita income jumped almost 58 percent between 1969 and 1975, from $2,859 to $4,515. Several multinational corporations, such as Rockwell International and FMC, have set up shop in the area.

The catalyst for Robinson’s entry into Tupelo was an incident involving Eugene Pasto, a Memphis man picked up by Mississippi highway patrolmen in March, 1976, and taken to the Tupelo police department on check forgery charges. After questioning by police captains Dale Cruber and Roy Sandefer, Pasto signed six confessions and six forms waiving his constitutional rights. Last January, a federal judge awarded Pasto, who was by then serving time in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta, $2,500 in his lawsuit against the officers for beating the confessions out of him.

Cruber, who received the “Officer of the Year” award in 1974, and Sandefer were both longtime veterans of the Tupelo police force. Prisoners had frequently charged at trials and in complaints to the FBI that the pair’s success came from beating confessions out of suspects. After the federal court’s decision in the Pasto case, more complaints began reaching Tupelo’s board of aldermen, along with demands that the two be fired.

The seven-member board voted to suspend the officers while Police Chief Ed Crider investigated the matter. Crider, who is elected to his post, concluded that the officers had not committed a crime; he claimed to know of no other complaints involving the two and recommended that they be reinstated. On February 24, 1978, the aldermen accepted Crider’s recommendation over the sole dissenting vote of Boyce Grayson, the only black alderman, who entered an unsuccessful motion that the officers be fired.

The city’s action provoked an angry response from Tupelo’s blacks. The United League seized the opportunity and stepped up efforts to organize a Tupelo chapter. Robinson lashed out at local black leaders who sought to solve the problem through further meetings, exclaiming, “You can’t negotiate from a position of weakness.” In early March, the United League began sponsoring a series of marches, drawing 400 demonstrators at the first, then 800 one week later. While Tupelo’s mayor, Clyde Whitaker, called the Pasto incident a “dead issue,” the League escalated its demands to include more jobs for blacks in city government and local businesses. The city made a last-ditch attempt to avoid a League-sponsored boycott by transferring Cruber and Sandefer to the fire department. The League rejected the city’s effort and on Good Friday began a boycott of downtown, stores.

The boycott was so successful that Lewis Myers, Jr., the League’s attorney, says, “White merchants from the two largest stores in Tupelo have personally come to me, pleading for an end to our boycott. The black boycott of white-owned stores has not only had an economic effect; it’s causing an emotional breakdown in the white community.”

The activity is unprecedented in Tupelo, which was largely bypassed by the tumult of racial battles over school desegregation and voting rights that raged across Mississippi a decade ago.

The rise of black protest in Tupelo has brought a white militant backlash, including formation of a Ku Klux Klan klavem. Douglas Coen, a former Pennsylvania policeman who moved to southern Mississippi five years ago, spearheads the backlash. Coen is now Grand Dragon of the Mississippi Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

“Whites are in a hole,” says Coen, “and we have to get back to level ground before we can start making any gains. The white working man has been stripped unreasonably and punished unreasonably for something he never had anything to do with. He was not the cause of slavery.”

While Coen is against the black movement — “we want the threats of black pressure removed from Tupelo’s streets” — he is not unhappy with the loss of business the boycott has created.

“The white merchants survived before they had the nigger business,” he said, “and they’ll survive a lot better after they get rid of the blacks.” He claims the Klan was needed to instill unity in whites. “Blacks recognize now that there is a white resistance to intimidation,” he said. “But had there not been, had we just kept giving and giving, there would be no end to their demands, and they would turn this city into a mass ghetto, unfit for habitation by any decent, self-respecting Christian.”

When fewer than 100 whites turned out for the Tupelo Klan’s first rally, the speakers blamed “white apathy” which they said could ruin the country. But three weeks later, that number was tripled when the Klan and the United League both demonstrated on May 6 in a dramatic confrontation.

The May 6 showdown began with a Klan press conference at the local Ramada Inn. By the time the League march started, reporters from CBS, NBC, the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times had arrived. United League members assembled in a black neighborhood and silently made their way toward the center of town, led by men driving pickup trucks, with rifles prominently displayed in their rear windows. The demonstrators carried anti-Klan signs and were flanked by League scouts armed with clubs, binoculars, and walkie-talkies.

Every policeman on Tupelo’s 65-man force was on duty that day; a helicopter hovered overhead and officials from the US Justice Department, sent by the Attorney General, monitored the situation. Everywhere one turned, pickup trucks and cars bearing rifles and guns were obvious. Ku Klux Klansmen, some wearing white hoods, patrolled the streets threatening to make “citizens’ arrests” of the demonstrators. In mid-day, a Klan motorcade drove down Main Street while blacks, bearing anti-Klan signs, watched from the sidewalks.

Nothing more than words were exchanged. But that night a Klan rally and cross-burning ceremony drew 300 people who demanded the reinstatement of Cruber and Sandefer. The two officers had announced two weeks earlier that they were resigning their positions in the fire department “with the hope that demonstrations by the United League of north Mississippi be terminated.” The United League quickly rejected this suggestion.

The crowd at the Klan rally was vocal and emotional, and participants frequently shouted racial slurs against blacks. At one point, Cruber acknowledged the crowd’s support with a Nazi-type salute. At the cross-burning, Cruber tried to pull the camera from the neck of Joseph Shapiro, a reporter for the Memphis Commercial-Appeal assigned to the paper’s Tupelo bureau. Another reporter stepped in and broke up the trouble.

Several days after the events of May 6, Tupelo city officials passed a resolution asking both groups to leave town and barring them from further use of the city facilities. When each group continued its plans for another showdown on June 10, the city passed an ordinance on May 18 prohibiting demonstrations for 90 days.

With the aid of North Mississippi Rural Legal Services, the League promptly challenged the ordinance in federal district court. At a hearing on the matter, city attorney Guy Mitchell warned that a “holocaust” could occur if the city could not forbid the demonstrations. The city paraded 25 witnesses, including all the aldermen, the police chief, several newsmen and residents. Newsmen testified that they had seen Klansmen at the May 6 demonstrations with flame throwers, hand grenades and submachine guns. City officials spoke of a “highly inflammable” situation and said that Tupelo was “permeated with fear.” But US District Judge Orma Smith struck down the ordinance as a violation of the right to peaceful protest. It marked the third time Judge Smith had ruled in a League lawsuit based on the First Amendment. In his two previous rulings, Smith had ruled against the League and been reversed by the US Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. This time, as he read his decision before a packed courtroom, Smith quoted from 13 lawbooks stacked on the bench in front of him.

Smith encouraged the city to draft another ordinance that could regulate the two marches to keep them from coming into direct conflict. But in the days preceding June 10, city officials rejected efforts by Alderman Grayson to find such an alternative and waited for the potential outbreak.

When the day arrived, the media, the helicopter and the full police force were once again on hand to observe. This time the police wore bullet-proof vests and riot helmets and waved shotguns and rifles. More than 700 people marched with the United League, including members of the state ACLU chapter, who held their annual meeting in Tupelo that day because, in the words of one member, “we do more than talk about civil liberties.” The march lacked the show of arms so obvious in previous demonstrations and passed without trouble. League demonstrators wrapped up their rally on the steps of the courthouse, while Klansmen waited a few blocks away to begin their march.

Then, about 50 robed Klansmen and 150 supporters marched to the courthouse while onlookers lined the streets. But the mood quickly changed. Bill Wilkinson, Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, was speaking to the crowd when a white man wearing a T-shirt that bore the United League slogan “Justice for All” shouted out, “You symbolize hatred. You call yourself a Christian!” Wilkinson directed some Klansmen to take care of the man, who was later identified as David Ohmes, a lay minister. Klansmen dragged Ohmes and knocked him to the ground; the minister offered no resistance. Tupelo police stepped in, saying, “Let us have him,” and began striking and gagging Ohmes. Reporters who tried to photograph the incident were told to stop, and one was pushed away. When the Commercial- Appeal reporter, Shapiro, began to argue, he was dragged to a waiting police van and tossed inside, while the crowd cheered.

Shapiro later described the incident: “As the van drove off, from the floor I heard the driver gleefully radio headquarters, ‘We got Shapiro.’ ” Shapiro said police complained of his earlier news reporting and advised him to leave town. He was charged with conspiring to incite a riot and assaulting police and interfering with police. Ohmes was charged with inciting a riot.

Reporters rushed to the police station to get more information. With them was Freddie Crawford, a black Justice Department official from Atlanta who stood in the station’s reception area and waited for police to let him inside so he could talk to the mayor. A white man in his late 50s walked in and said to Crawford, “Well, look at that goddamned nigger.” Crawford, incensed, whipped around and demanded, “What did you say?” The white man, who turned out to be H. D. Cruber, father of one of the former officers, moved through the reporters and began pulling on the door, brushing up to Crawford and demanding to get inside.

Crawford flung his fist at Cruber and threw his tape recorder, which narrowly missed Cruber’s head and flew through the plate glass front window of the police station. The two men grappled to the ground. As reporters moved out of the way, police officers poured in through the door and over a side counter. They first grabbed Crawford, who shouted, “What is the matter? Won’t you grab him because he’s white?” Some police then grabbed Cruber, and Crawford flung off the officer holding him down and grabbed him from behind. A second Justice Department official grabbed another police officer, and for a moment the scene was frozen in an amazing standoff: two black Justice Department officials holding two Tupelo policemen, a third policeman holding Cruber, while reporters stood by in disbelief. The officers confiscated a length of chain from Cruber, and Crawford later said he started the fight after he saw Cruber reach into his pocket where the chain was. Cruber was charged with assault. On a day that city officials had said would inevitably lead to trouble, the only scuffles involved police.

Skip Robinson, 42-year-old brickmason and building contractor, blends fiery rhetoric with preaching in speeches that have moved his audience to tears. He calls on blacks to find their own leaders; and when he speaks of having “found a cause worth dying for,” a comparison to Martin Luther King, Jr., seems inevitable. Since forming the League, Robinson has at times sought local political offices such as mayor and sheriff, prompting critics to charge him with opportunism. Among those to accuse Robinson of inflaming issues to grab headlines are Mayor Sam Coopwood of Holly Springs and Mayor Clyde Whitaker of Tupelo.

Indeed, Robinson even incurred some initial resentment from local black leaders as an outsider in Tupelo. When the League first came to town, John Thomas Morris, head of the area’s NAACP, criticized the organization for pushing the city’s own black leaders aside. But after the League won a recent lawsuit against the city ordinance banning League and Klan demonstrations for 90 days, Morris stood on the courthouse steps and declared, “City leaders are going to have to learn they can’t pick who the leaders should be for black folks.” When Judge Smith struck down the ordinance, he said one of the “major issues” causing the city’s problems was the “inability of some people in charge of city affairs to accept the fact that people can come in from out of town and take a leadership role.”

Leadership is Robinson’s strong suit, and he has almost single-handedly directed the League’s effort. He drives from city to city, trying to set up organizations with little to offer other than personal support and the concept of unity. As an emerging black leader, Robinson is vulnerable to politicians seeking support. One week before the Mississippi Senatorial runoff, Robinson had to call a press conference to explain why the campaign of Gov. Cliff Finch had paid him $1,375. Indeed, while the League’s grassroots strength is one of its major assets, its lack of money does have drawbacks. The League had no office or staff. It has, however, an important ally in North Mississippi Rural Legal Services (NMRLS), a branch of the federally funded legal services network governed by local communities. Robinson works out of the Holly Springs office of Legal Services, and Lewis Myers, Jr., director of litigation for NMRLS, serves as the League’s attorney. Legal Services staff member Henry Boyd, Jr., is the League’s secretary.

Myers, a 30-year-old Houston native, studied law at Rutgers University. He came to Mississippi six years ago through an exchange program between the law schools of Ole Miss and Rutgers and decided to stay. Myers takes part in the League’s weekend marches, files suits on its behalf and represents it in negotiations over grievances with local governments and businessmen. The close relationship rankles many public officials.

Recently Tupelo’s aldermen, with only Grayson dissenting, called for a federal investigation of the ties between the League and the Legal Services office. Myers has recently received an official notice from the Legal Services Corporation’s regional office in Atlanta that he is under investigation and facing suspension from the program, based on complaints from the mayor and board of aldermen of Tupelo and the local bar association. Myers is charged with violating a section of the Legal Services Act that prohibits the corporation’s lawyers from taking part in and encouraging public demonstrations. Myers’ case will be the first prosecution under this section of the act.

The impending investigation will not be the first for the League. During the height of the 1974 Byhalia protest, requests from Mississippi Senators James 0. Eastland and John C. Stennis prompted a similar probe. Because most League members qualify financially for Legal Aid, Myers was cleared of any wrongdoing. Since then, the federal act has been rewritten.

“I think it is clear that some people would like to see me stopped because they do not like my outspokenness,” Myers said, “but I have First Amendment rights, too. Can the (Legal Services) Corporation tell me that I can’t spend my weekends supporting a cause I believe in, supporting the cause of my clients?” With help from NMRLS, the League has won landmark cases on voting rights, education and employment issues. In Holly Springs, says Myers, the League won the right for students at predominantly black Rust College to vote in local elections. In 1970, the League blocked an attempt by Holly Springs officials to redraw district lines without the approval of the Justice Department in violation of a federal voting rights law. The League also was able to force the city to change from at-large elections to single member districts. Before this, there were virtually no black elected officials, says Myers. Now, blacks are represented on the school board, the election commission and the board of supervisors.

The League has not only won the right to vote for thousands of blacks, says Myers, but has encouraged them to register and to exercise that right. The League also encouraged blacks to serve on juries.

The League pursues economic as well as political goals. “We’ve gotten more people around here jobs than Mississippi Employment Service,” says Myers. “We are willing to stand up against lawlessness as well, and black people now look to the League when something happens.”

But as the League grows in effectiveness, it draws increasing intimidation and harassment. In Holly Springs, a cross was burned at Robinson’s church one day after a march started from that building. A bottle filled with blue spray paint, apparently fired from a tear-gas gun, exploded into the home of League secretary Boyd. The League responded with stepped-up security, including patrols through Holly Springs’ black neighborhoods at night. Now, when Robinson appears at rallies, two bodyguards protect him. “We’re non-violent,” he says, “but our freedom has been jeopardized. If we have to walk over a person, we’ll do it.”

League attorney Myers echoes this determination. “My knees won’t bend,” he told a cheering crowd on June 10. “If I have to die in this country, I want to die on my feet, not on my knees. We have won the dignity of our people back.” This, Myers believes, may be the League’s greatest achievement: “If it’s done nothing else, it has brought black people together in a bond of solidarity and pride that is unparalleled in this area. We are no longer afraid.”

Tags

Fredric Tulsky

Fredric Tulsky is a reporter for the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, Mississippi’s largest newspaper. (1978)