Fayette County, Tennessee: Sick for Justice

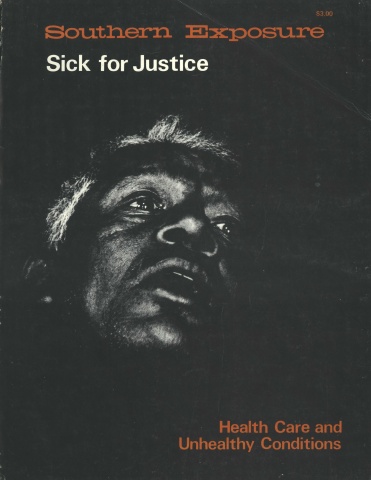

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 2, "Sick for Justice: Health Care and Unhealthy Conditions." Find more from that issue here.

The Rossville Health Center is in many ways a continuation of the civil rights movement in Fayette County, which Robert Hamburger eloquently documented in Our Portion of Hell. The experience of board members with previous struggles and the close relationship of the board to local churches (three of the original board members are preachers) prepared the Poor People’s Health Council for the political battle necessary to bring meaningful health care to Rossville. The resulting integration of the board’s view of politics and theology is best evidenced by their unique perspective on the health center as analogous to Israel’s source of deliverance from the bondage of Egypt, rather than simply as a small business or even an innovative community clinic. One man who exemplifies that perspective is Square Mormon, president of the Poor People’s Health Council which runs the clinic.

I serve as Chairman of the board, and we have thirteen members now on our board. The Council makes a policy and we look out for the welfare of the people. We’re trying to construct a building and we’re trying to get more trailers as our clinic grows larger. We set plans and policy like that. We also do more than just run the clinic.

Me and the people that started with me in 1960 in the civil rights movement before the clinic existed, we were working for poor people back then. In the beginning, when there was so much heat in Fayette County, the landlords were sort of confused by our people registering to vote. Lots of people had stayed on their land for numbers of years and some of the black people of Fayette County thought that the landlords were their best friends and if you told some of them that the landlords weren’t their friends at that time, you’d have had a fight.

But when they attempted to register to vote in ’60 — at that time the black population was about seventy-five percent of Fayette County — the white, they knew the population of Fayette County. They thought if the Negro got all registered up and raised up about justice and right — they thought the black folk would try to take over everything. This upset them very much because they could see things that the black wasn’t thinking about. The black didn’t want to run Fayette County; they wanted to be a pari of Fayette County. They wanted to be of citizenship in Fayette County. They warned to send their children to the best schools and whatever the system of the federal government was, they wanted to be equal in it. But I don’t think the white understood this. They thought that the black would try to pay them back after the way they’d been treated down through the years from the slave owners and the plantations.

We could understand that they looked at it in another different way. They had it drawn out in another picture. Maybe some were so prejudiced they feeled that they shouldn’t be on the level with the black man, but howsoever, we were determined to explain and to show them and to tell them what we wanted. We wanted to be heard, we wanted to be part of the federal government, and we wanted to make sure that our people were not the last to be hired and the first one fired.

That was a hard task, but the Negro was determined and we continued to register and continued to try to send our children to the best schools, and we continued to try for higher wages so that the Negro would be paid as the white was paid. We wanted to be paid by our qualifications. For a long time we went through a lot of suffering before we could demonstrate to the whites that these things were right. So we put the pressure on them through ’59 up through the ’60s up to ’70.

So these are the things that we thought were wrong. The people in Fayette County, when their eyes came open, they really had got sick for justice and they were willing to pay any kind of price to be paid to be heard.

As we were working in the movement, we began to seek around, to find out what we could do for health care. So at that time, we had a little freedom school going that was very successful. We were reading about Negro history and people back when they couldn’t read or write, and how they fought for justice. So one day we were talking about considerations for health care, how we had no doctor. No doctor in Macon, no doctor in Moscow, no doctor in LaGrange. We had a lady coordinator by the name of Virgie Hortenstein at the freedom school. We said to her, “How can we get a clinic together? Do you have any experience, do you know how we go about getting a clinic?” She helped arrange a meeting with Dr. [Les] Falk and Dr. [Ernie] Campbell of Meharry and they advised us at that time to keep on organizing ourselves and keep on getting together organizing ourselves, and they would go back to Nashville and they would be in touch with us.

They went back [to Medical College] and talked to the students about their interest in working with people who would like to have a clinic. And the students at that time were going different places and having health fairs and they thought that west Tennessee would be a good place where they could set up and get going. And it was because we had a dream of health care because we had seen so many of our people suffer and die for health protection. And so some of the students came down, and I talked with them and we asked them what could we do, because we insisted that they come down.

They said, “We would need some homes because there would be students coming out of school and they would need a place to stay.” And I said, “That would be no problem. As bad as we need a clinic and as bad as we need our people to be examined we will do everything we can.” We asked them, “How many homes would you need?” And they said, “We would need twenty-five or thirty homes.” We went out and got forty homes. We had more homes than we had students.

At that time, we had a movement called the sheet movement. We went around to a lot of people and we got a lot of sheets from different ones, so that those who were keeping the students who didn’t have enough sheets, we would give them two or three sheets for the students to sleep. We called it the movement, the sheet movement. We had sheets, I mean, even when we started the health fair, we had sheets to make partitions for the people to be examined.

The first year we started the health fair we couldn’t get a school from the board of education, and it was just like it was when Jesus was born. We didn’t have nowhere for the students to come to examine the people and bring all these good ideas and opportunity to bring health care. But we had faith because of the students.

Some of the people working on it were from the civil rights movement and worked with me, and many of the officials of Fayette County looked on us as old troublemakers. However, we went to them and sat down with the power structure and we explained about the health fair to them. Each person explained why we were interested in having a health fair. They kept listening to our story. I was about the last one to testify.

I said, “My concern in being here, as living in Fayette County — I was born and raised here — and I know the problems of our people, my people.” At this time our doctor, Dr. West died. There were a lot of farmers in the field who lived away from him out in the ghettos and in the thickets, you might say. You know, these houses that sit out on the old dirt roads, the old plantations; and we were sometimes a mile from the gravel road. We had to come out a dirt road about a mile to come to the gravel road and then we’d go over the gravel road and, you know, we didn’t have any hard tops until ’57. We saw numbers of our own people die for lack of attention for health care. Even if you called a doctor, they’d have to come from twenty-five miles away. So I said, “I’ve seen so many of my peoples die without doctors since the death of Dr. West. We sit down in Rossville, twenty to twenty-five miles from Somerville and thirty-five miles from the Memphis hospital, and see babies die for attention and people get sick and die for attention.”

I remember at that time a white man rented a place down here. He took sick one night and they called the ambulance from Somerville to come and get him. I told them, “Just like Mr. Campbell, a lot of you all know him, took sick the other night.” And I said, “He got sick and they called for the ambulance and it was like an hour coming, and they put him in the ambulance and on the way back to Somerville the man died.” And I said, “I think if we had a clinic with doctors it is possible that that man would be living. I think that that man died for lack of attention and I know numbers of babies died for not having doctors.

“We have had midwives who do their best, but when a woman has problems, we would call a doctor and sometimes it was too late. You know with 23,000 people in Fayette County, I feel like the clinic should be like churches. The churches are where the people are at. You should bring the church and the clinics to where the people are. I think that people are very interested in putting this together and I think it is possible and this is my concern today.”

We sort of convinced the power structure that night. I remember the meeting; I was very surprised. Dr. McKnight said, “I have to say, there is a need for a clinic and for more health care, so I will say that I am in favor.” Then I think Sister Guthrie asked him, “Would you make a motion?” He said, “Yes, I will make a motion that I am in favor.” Then it was approved by the Quarterly Court and the Board of Education that we could have a health fair.

We only got approval at the time to have a health fair. The clinic was kept back because it was decided that we wouldn’t come out with all of it at one time; we would just say health fair. And at the same time, while we were having the health fair, our dream was to organize ourselves, get us a charter, then we would go back a little more efficient and then set up a clinic.

There were difficult problems when the power structure found out that we were trying to buy land to set up a health center. They never understood a brand new organization setting up on their own. Some of them said to me, “Now I can understand if the state was setting up a clinic, but I don’t understand you setting up and trying to support a clinic on your own.” It was a very strange thing to them because they had never seen anything like that happen, and I said, “Well, I feel like the state should have already had the clinic set up here because the state knows the people don’t have health care in Rossville and the people knows it and the power structure know it, but the Bible says, ‘The Lord helps those that helps themselves.’”

And as I remember, one time in the civil rights movement when I was going around raising people into getting schools integrated, some of the power structure told me, “Square, can’t you find something else to do to help your people besides making trouble?”

So I laughed and I said, “I hope I’m not making trouble.” I said, “I don’t look at having black children going into schools that were called white schools like you look at it. I look at it as if it’s not white schools. It’s not black schools — it’s government schools and all the taxpayers have the same right to go to that school. They have the right to the best of schools. I would like to see my child have the same books and the same opportunities and deal with inside restrooms just like anybody else. And we’re all human. We’re all human and I don’t think we ought to be divided like this. We should be treated human and equal under law.”

So he says to me, “I know what you’re saying and that sounds well, but I just thought there might be something else you might be doing.”

When we thought about health care, I thought we wouldn’t have the same old difficult problems because we weren’t registering people and we weren’t trying to integrate schools. But when we went to try to do something for ourselves, we caught as much hell in just trying to set up a clinic and trying to raise money.

We felt like charity should start at home and spread abroad. The beginning money the Poor People’s Health Council raised was a hundred out of their pocket and then we went to the churches, and the churches contributed money for a building. Then some of the people working at the health center, they had programs, we had picnics to raise money. The whole thing we were trying to do was to show the power structure, to show the federal government, and to show everyone that we wanted to do something for ourselves and hoping that they would join in with us.

I believe that you don’t stand up and tell someone to do something for you, but you first do something for yourself. The people see that you mean something and that you struggle along with the difficulty and the problems that you’re having and you don’t stop at that and you’re disencouraged and you pray about it, and you read and meet about it, and you ask God for knowledge and faith and more understanding and you work with all your cares and you have to ask God to give you courage to go where you said you weren’t going to go and go further when you thought you couldn’t go any further; that’s the way you keep on moving.

That’s the same thing in the civil rights movement when things got so bad. I would come home and I would wonder why things happen like this and if I could go any further, then I would think about what King said: “If you haven’t seen anything worth dying for, then you’re not fit for living anyhow. If Jesus had problems, he didn’t have no sin, he didn’t do no wrong; he was perfect and if he had a hard time, what about you.” So I think about all those things, and I build up more encouragement to go back and continue and still fight. I felt down the road somewhere that if you keep working that reward was somewhere. So that way we kept going. We kept trying to buy land.

The planning stage of our clinic upset our doctors, some of the doctors got upset, after the board raised the money, after the church raised some money. We had people raise money and after some of the clubs had given us a hundred dollars and it looked like we were getting together, and TVA donated trailers. We put in a proposal for $30,000 to the state and this needed doctor approval. I got Mayor Farley to write a letter of support. And this helped so much. I went to a doctor and I got turned down. He said to me, “Square, I just don’t understand. I would sign it but I really don’t understand your organization. I’m not against you, but I don’t know enough about it.”

Well, I couldn’t convince him to sign it. But we went on with the endorsements we got, and through the help of the board, it passed. We had to go to Brownsville one night, and we had to meet all the doctors from around; the union of doctors that make decisions about things. And we got two or three carloads of people. Dr. [Erica] Voss went with us, myself, A1 Nelson, we carried along four or five board members, we carried some of the council members, some interested citizens.

We got to Brownsville that night and Judge Rice, he’s our judge, he found out, he told us they wouldn’t let but two people into the meeting, me and Dr. Voss. He told me, he said what they were most concerned with was Dr. Voss’ qualifications and that I should let her answer the questions they asked. That’s okay, 1 can take care of myself. Dr. Voss, she can take care of herself. We were in there for an hour and a half. They asked Dr. Voss about her qualifications, her education. Dr. Voss convinced them she was qualified for her position and they agreed we should get the $30,000. That’s just about some of the history of what we had to go through to get started with the clinic.

The clinic has made things better between blacks and whites in Fayette County. Some of the blacks, and a lot of the whites said it couldn’t be done. We had convinced them it could be done. By setting up an integrated clinic, blacks and whites, a white nurse, a white receptionist, a black doctor, a black receptionist, we have shown that it could happen. It hasn’t been easy. Some of our professionals walked off at times because our clinic was a black movement. It was an unfair thing to happen, but it happened. They fell out with the name of the place, the Poor People’s Health Center. It had become a shocking name. They explained that the uneducated black was shocking to them, but it wasn’t shocking when they came and the money flowed. They seemed to have forgot about health care. They began to look for fault. And they began to look to set up a clinic like they would like to see one come, destroy our ideals, our goals and to disencourage the black nation like throughout history, that this was impossible for black people to do.

The clinic has also made things better between black people and the power structure. At this time we have seven board members of some of the old civil rights movement leaders. Now at this point we have whites on the board: a representative from the Welfare Department, a representative from the Tax Assessors Office, from the Board of Education, the Mayor of Rossville, and others. Now when we have a board meeting we’re able to sit down and talk, and we ask them for input and they’re willing to give us input.

We don’t have static from our local people at this time, and it seems like everybody wants to see a permanent building here. We also have whites come into our clinic, young and old, poor and middle class, and upper class. So we also have black and white working in the clinic. We also have a minibus that takes black and white to the clinic and to Memphis. So it has brought a better spirit, a better relationship. If we can work with all our friends and foundations, the federal government and the state, and we can convince them that we need a building and a facility that we can call home, then we will serve the unborn generation and the peoples from everywhere. Then people from everywhere can say, “This is ours.”

I wanted to see a clinic built that our young people could be trained and be lifted by their bootstraps and would be able to come into health care training, nurses. I wanted to see something where students from Vanderbilt and Meharry could come out and have a place to go that they would have a chance to serve people black and white.

My whole goal was to see other organizations, another wing on the health center like maybe day care, social workers, and we could have something that would test water. So many people got sick and so many diseases that we felt like we could have something to check out all the wells, and we could have social workers go around and check people’s houses for screens, check babies, see how they are treated, give advice to young mothers who might not know how to take care of children and to continually set up different day-care centers and maybe someday look after old folks, or even maybe have a bus that could move around different places and still give service. So this was some of our goals and our dreams in setting up a clinic, to see as we grow, to see what could be set up that could bring better health care and more enlightenment to our people. This is the movement’s dream today.

Tags

Richard Couto

Richard Couto, Pat Sharkey, Paul Elwood, and Laura Green — all affiliated at the time with the Center for Health Services at Vanderbilt University — conducted an extensive evaluation of RCEC for the U.S. Department of Education in 1986. This article is adapted from that report. (1986)