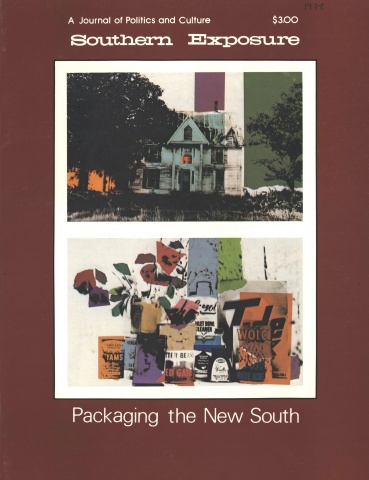

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 1, "Packaging the New South." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

From 1938 to 1939, over a thousand Southerners told their life stories to writers employed by the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), a New Deal program. They lived in a rural, impoverished and segregated region. For many of them, time was measured less by calendar and clock than by season and task — planting, laying by and harvesting. They worked on farms, in mills, oil fields, coal mines and other people’s homes.

Most of the people interviewed were already poor before the Great Depression; after 1929, things only got worse. Their life histories provide a view of the world they saw, experienced and helped create. They tell about growing up, getting married, having children, prospering (or not), getting old. They describe how major events — the Civil War, Emancipation, World War I, the New Deal — affected them. They talk about race relations, family life, sex roles and religious beliefs.

Almost as interesting as the life histories themselves is the story of how they came to be collected. The Federal Writer’s Project was a government experiment in work relief and sponsorship of the arts, the product of the needs and hopes of a specific time. As part of the Works Progress Administration, the FWP tried to offer meaningful work to unemployed writers. It centered its efforts on the production of a series of multi-authored state guides. Equally significant were such programs as the recording of ex-slave narratives, some of which were published in Lay My Burden Down (1945), and the Southern life history project.

W.T. Couch, regional director of the FWP in the Southeast and director of the University of North Carolina Press, supervised an extensive program for collecting the life histories of common Southerners. He thought and worked in a cultural context in which the South had become an important symbol of the nation’s economic problems; he was influenced by Southern intellectual developments such as Agrarianism, and by Northern response to Southern problems. The sudden end of a seemingly endless prosperity had brought new attitudes and programs to the forefront of national attention. Couch’s vision of the work the FWP should undertake grew out of his reaction to these currents of thought.

The dominant criticism of American life in the 1920s had focused on the shallowness of middle-class life, the excesses of prosperity and the backwardness of large segments of the population. The South, along with Main Street and Winesburg, Ohio, provided critics with the symbols of much that they found wrong in American life. In the 1930s, the South continued to symbolize the nation’s problems. As one historian observed, “The Bible Belt seemed less absurd as a haven for fundamentalism, more challenging as a plague spot of race prejudice, poor schools and hospitals, sharecropping and wasted resources.”1

Much of the writing that made the South in the 1930s a symbol for the Depression focused on the plight of the Southern tenant farmer. More than any other book, Erskine Caldwell’s Tobacco Road (1932) inaugurated the new interest in Southern tenant farmers. The world he created was inhabited by degenerate, stunted and starving people. Couch found little to admire in Caldwell’s Tobacco Road or in his volume of impassioned reporting, You Have Seen Their Faces (1937). Moreover, Caldwell’s plea for collective action on the part of tenant farmers and for governmental control of cotton farming failed to impress Couch, who remarked

If tenant farmers are at all like the Jeeter Lesters and Ty Ty Waldens with whom Mr. Caldwell has peopled his South I cannot help wondering what good could come of their collective action. Nor can much be expected from government control if the persons controlled are of the type that Mr. Caldwell has led us to believe now populate the South.2

Like Couch, the Nashville Agrarians were dismayed by Caldwell’s portrayal of the South. The Agrarian manifesto, I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition (1930), had rejected industrialism and idealized a simpler agrarian economy. Though Couch objected to Caldwell’s gloomy assessment of the region’s people, he insisted that “the South must recognize that conditions of the kind Mr. Caldwell describes actually exist in this region, and must do what it can to correct them.” He took issue with the Agrarians who, he said, “assert that virtue is derived from the soil, but see no virtue in the Negro and the poor white who are closest to the soil.”3

More liberal than the Agrarians and yet no less critical of Caldwell’s work, Couch developed an idea of his own for examining Southern conditions. He wanted to give Southerners in all occupations and at all levels of society a chance to speak for themselves. Collecting life histories was one way of doing this.

Couch was convinced of the advantages of life histories over more conventional methods. He thought that Southerners speaking for themselves would demonstrate that Southern life was more complex than easy generalizations had led people to think. In discussion with other FWP officials, he argued against “the possible objection that only sociologists can get case histories that are worth getting. The fact is that when sociologists get such material, they generally treat their subjects as abstractions.” He thought fiction was equally inadequate because of its “composite or imaginary character.”4

Only by permitting individuals to tell their own stories from their own points of view, Couch thought, could the statistical and sociological evidence already gathered be given meaning and *See Bob Brinkmeyer’s retrospective appraisal of Erskine Caldwell in the book review section. context. What can we learn, he wondered, from knowing that the average sharecropper moved frequently unless we understand what it means to him in the context of his own life? Underlying Couch’s emphasis on the worth of material “written from the standpoint of the individual himself” was a strong commitment to democratic values.5 There had been, he argued, numerous “books about the South...written from other books, from census reports, from conferences with influential people.”6 And on the rare occasions “when the people have been consulted they have been approached with questionnaires in hand and with reference to particular problems of one kind or another.” This, he thought, was unsatisfactory: “With all our talk about democracy it seems not inappropriate to let the people speak for themselves.”7

The democratic impetus of the life history program was reflected not only in the voice of the people, which had seldom been heard before, but also in the way the material was gathered. Field workers far removed from the decision-making about the life history program collected the actual materials. In areas like the Southeast where there were few unemployed writers, the FWP employed literate middle-class individuals who were out of work. Themselves victims of the Depression, they were not far removed from the people they wrote about. Most had been born and reared in the South, and some, like Bernice Kelly Harris, wrote histories of people they had known all their lives.8

Field workers approached those they did not know in a casual and random manner. Ida Moore remembers choosing “the people to be interviewed more or less by instinct...saying I’d like very much to stop by for a few minutes and talk with them. ”9 This friendly sharing “of a few minutes” between neighbors perhaps explains why, unlike much similar material, these life histories do not seem to have been cajoled from beleaguered and defenseless individuals, unsure of how to cope with people who wished to study them.

The life histories submitted by the field workers often had to be edited by more competent writers on the project. The field workers, however, possessed qualities that more than compensated for their lack of writing skill. William McDaniel, the director of the Tennessee Writers’ Project, remarked of one relief worker, “Her greatest attribute is that she is one of the people. She shares their views, religion, and mode of living, and through that gets into her stories the essence of their community life.”10

Relying on their personal, and occasionally eccentric, understanding of what was required, field workers went about their task, picking their own subjects for their own reasons, and often taking great liberties in following the suggested interview outlines. This meant that the life histories collected constituted a skewed sample of Southern life. Middle-class individuals, for instance, were under-represented. It also meant that the life history collection represented not a single vision of who and what was significant in the South, but a collective one.

In 1939, thirty-five of these life histories were published in the critically acclaimed These Are Our Lives, edited by W.T. Couch. Plans to issue more volumes were abandoned when rising opposition to the New Deal forced the FWP to curtail its most innovative projects. In the spring of 1978, the University of North Carolina Press will publish more of these life histories in Hirsch and Terrill’s Such As Us. From the perspective gained with the passage of forty years, these stories can now be read as vivid chapters in the social history of the South, reaching as far back as slavery times and as far forward as the eve of World War II.

The following excerpts are from three of the FWP life histories, and are included in Such As Us. The editors have changed the names of the people mentioned in the life histories to protect their privacy, but left the names of the original interviewers, where known.

FOOTNOTES

1. Dixon Wecter, The Age of the Great Depression, 1929-1941 (New York: Macmillan Co., 1948), pp. 159-60.

2. W.T. Couch, “Landlord and Tenant,” Virginia Quarterly Review 14(1938): 309-12.

3. Couch, “Landlord and Tenant,” p. 312; W. T. Couch, “The Agrarian Romance,” South Atlantic Quarterly 36 (1937): 429.

4. [Couch] to [?], “Memorandum Concerning Proposed Plans for Work for the Federal Writers’ Project in the South,” 11 July 1938, Federal Writers’ Project, Papers of the Regional Director, William Terry Couch (hereafter cited as FWP-Couch Papers), Southern Historical Collection, University of North Caro Una Library at Chapel Hill, NC.

5. Federal Writers’ Project, These Are Our Lives, p. x.

6. Couch to Douglas Southall Freeman, 25 March 1939, FWP Couch Papers.

7. Federal Writers’ Project, These Are Our Lives, pp. x-xi.

8. Bernice Kelly Harris, Southern Savory (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1964), pp. 181-205, offers an informative account of one project worker’s experience and what it meant to her.

9. Mrs. Ida Cooley (formerly Ida Moore) to Jerrold Hirsch, no date.

10. Letter, McDaniel to Couch, January 20, 1939, FWP-Couch Papers.

NOTE — Southern Exposure does not normally publish interviews in heavy dialect. However, in the 1930s, interviewers worked without the benefit of tape recorders, and we thought that we must adhere to a faithful reproduction of the writer’s transcription. Perhaps we may learn as much about the writers as their subjects.

“I Was a High-Minded Young Nigger”

1939, Charlie Holcomb, Johnston County, North Carolina. Interviewer unknown.

Original title, “Tech ’Er Off, Charlie,”from “People in Tobacco, ” an unpublished manuscript edited and partly written by Leonard R.apport. A copy of “People in Tobacco, ” is located in the Work Progress Administration Papers in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress.

“We has always been tenement farmers and my pappy before me was a tenement farmer. Used to be, when I was a young man, I thought I could manage my business better and dat I was gonna be able to own a place o’ my own someday, but day was always sumpthin come a long and knocked de props from under my plans. My ’baccer was either et up by de worms, or it was de rust or de blight, or poor prices — always sumpthin to keep me from makin’ dat little pot I planned on. And den time de lan’lord had took his share and de cost o’ de fertilizer and de ’vancements he had made, dey wan’t but jist enough to carry on till de nex’ crop.

“But Lawdie Lawd, dat was back when I was a high-minded young nigger and was full of gitup- and-git. Day wan’t nothin’ in de world dat I didn’t think I could do, and I didn’t have no patience wid niggers what didn’t look for nothin’ but sundown and pay day.

“...My gran’pappy lived wid us too, but he wasn’t able to do much work. He had de miseries in his back and walked wid a stick. But he was right handy ’bout things like sloppin’ de hogs and feedin’ de chickens. I was his pet chile, too, and he holp me out a lot in de little things a chile has to learn growin’ up. I was a frail chile and wan’t able to work in de fields like most chillun. And gran’pappy looked out for me. When dey was wormin’ and toppin’ to be done, he would take me to dig bait for him, and den we would go to de crick and ketch a mess o’ catfish. He used to do a heap o’ thinkin’ while we was sottin’ dar fishin’.

“I ’member once he caught a big, fat catfish and jist played wid him for a long time. He pointed to de fish and tol’ me to watch him. Den he lifted de fish outen de water and dat fish kicked and thrashed sumpthin tumble. Den he lowered de line and let de fish back in de water. When he did dat de fish jist swum around as easy as you please. Den gran’ pappy pulled de fish out on de bank and we watched him thrash around til he died. When de fish was dead gran’pappy turned to me. ‘Son,’ he said, ‘a catfish is a lot like a nigger. As long as he is in his mudhole, he is all right, but when he gits out he is in for a passel o’ trouble. You ’member dat, and you won’t have no trouble wid folks when you grows up.’ But I was jist a kid den, and I couldn’t make much out of it. I let dat plumb slip my mind, and later on it shore caused me a heap o’ grief.

“...One time atter I had sold all my ’baccer and de lan’lord took his share and de fertilizer money and de ’vancements out, it looked to me like I was gonna have a little left for myself. Den de warehouse man called me back and tol’ me he had figgered wrong and dat I owed some more warehouse charges. I knowed it wan’t right, and it made me so mad I jist hit him in de face as hard as I could. Den I kinda went crazy and might nigh beat him to death. I got twelve months on de roads for dat, and all de time I was away from home Dillie and de chillun had to try to make another crop, but ’course day couldn’t do so good by dayselves and Mr. Crawford, dat’s de lan’lord, had to carry ’em over. Hit took me three years to git him paid back.

“By dat time I knowed it wan’t no use for me to try to over make anything but jist a livin’. I was ’termined my oldest chile was gonna hab a chance in dis world, and I sent him all de way through high school. Willie was a mighty good boy and worked hard when he was at home.

“Atter he got outta high school he tol’ me dat a man wid jist a high school eddycation couldn’t git nowhere and dat he wanted to go to college. Me and Dillie talked it ober and we didn’t see how we was a-gonna do it, but we let him go to de A & T College. Will worked mighty hard and made good grades and worked out most o’ his way. In de summer he would come home and he’p wid de ’baccer and we made some mighty good crops. Willie would take de ’baccer to market and go over de accounts, and he was pretty sharp and always come home wid money in his pocket.

“De last year Willie was in school he started gittin’ fretful and sayin’ dere wan’t no future for a nigger in de ’baccer business, and dat he didn’t want to come back to de farm. Dat hurt me, ’cause I had counted on Willie helpin’ me, but I wanted him to do what he thought was best.

“When he graduated he was one o’ de brightest boys in de class, but dat was when de trouble started. Willie knowed he had a good eddycation and didn’t want to waste his time on no small job. But he couldn’t find nothin’ to do and he finally come home and started settin’ around and drinkin’ and gittin’ mean. I didn’t know what was de matter wid him, and tried to reason wid him, but he wouldn’ talk no sense wid me.

“Dat fall he took a load o’ ’baccer to de warehouse, and when he come back he was all mad and sullen and I knowed he had been drinkin’ again. All dat night he drunk and cussed sumpthin tumble, and de nex’ mornin’ his eyes was all bloodshot and mean-lookin’, and he had me scared. He said he was gonna take another load o’ ’baccer to de warehouse, and I didn’t want him to go, but he went anyway.

“‘Long ’bout dinnertime one o’ de neighbors come a-runnin wid his eyes bulgin’ clean out on his cheeks. He said dere had been a fight at de house and dat Willie had been hurt.

“I got on my of grey mule and rode into town as fast as I could. When I got to de warehouse I seen a bunch o’ men standin’ around and den I seen my Willie layin’ on de ground and a great puddle o’ blood around his head. I knowed he was dead de minute I seed him. For a while I didn’t know what to do. I looked around at de crowd and dey wan’t a friendly face nowhar. Right den I knowed dey wan’t no use to ax for no he’p and dat I was jist a pore nigger in trouble. I picked my Willie up in my arms and saw his head was all bashed in. Dey was tears runnin’ down my checks and droppin’ on his face and I couldn’t he’p it. I found de wagon he had driv’ inter town and laid him in dat. Den I tried my of mule on behind and driv’ home. I never did ax nobody ’bout what happened to de ’baccer he took in.

“When I got home I washed Willie’s head and dressed him in his best suit. Den I went out to let Dillie hab her cry. We buried him at de foot o’ dat big pine at de left o’ de well, and made some grass to grow on de grave. Dat’s de mound you was lookin’ at as you come up to de house.

“For a long time atter dat I couldn’t seem to git goin’, and dey was a big chunk in de bottom o’ my stumik dat jist wouldn’t go away. I would go out at night and set under de pine by Willie’s grave, and listen to de win’ swishin’ in de needles, and I’d do a lot o’ thinkin’.

“I knowed Willie had got killed ’cause he’d been in a argiment wid somebody at de warehouse. Den I got to thinkin’ ’bout what gran’pappy said ’bout de catfish, and I knowed dat was de trouble wid Willie. He has stepped outen his place when he got dat eddycation. If I’d kept him here on de farm he would a-been all right. Niggers has got to Tarn dat dey ain’t like white folks, and never will be, and no amount o’ eddycation can make ’em be, and dat when day gits outen dere place dere is gonna be trouble.

“Lots o’ times dere is young bucks dat gits fretful wid the way things is, and wants to cut and change, and when dey comes talkin’ around me I jist takes em’ out and shows ’em Willie’s grave.”

“And I can stretch that ten dollars out for the three of us.”

1938, Lola Simmons, Knoxville, Tennessee. Life History by Dean Newman, Jenette Edwards, James Aswell, FWP writers.

Original title, “Green Fields Far Away, ” located in the Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina library, Chapel Hill.

“Calvin and me come from the mountains, for Calvin knowed he could make a living in some way or another about town doing odd jobs. So we left the farm. We fared on down to Knoxville. Our times has not been easy here. But then times has always been hard with us. We was both born poor. Lived poor all our lives. All in all, though, it’s a lots easier making out here than it was back there on the farm. We ain’t never had to ask a penny off of no one. Never asked the government to put us on relief, neither.

“.. .This place here we live in, it’s not any great shakes of a place. But we’re going to stay on as long as we can. Every time we’ve moved from here to somewheres on the edge of town, Calvin’s lost work. Here he’s in close-catch of town folks that wants a job done right off. The biggest trouble about living in a basement like this is they’s not any room for spreading. Well, three rooms is enough for me and Calvin and Cap, even if they’s not big rooms. This here sitting room is space enough to hold the parlor furniture and Cap’s bed. Cap’s just only fifteen but he’s near outgrowed that bed back yonder. He has to lay catercorners of it now. Ought to be some way Calvin could stretch it out, seems to me. I don’t see no way we could put a double bed in that space even if we had cash to buy it — which we ain’t.

“Me and Calvin takes the back room. They’s no grate in it, but some heat comes from the kitchen. That kitchen has a sink with running water, and that’s the closest we ever come to having a bathroom. Well-a-day, not having such means less to us than most. Coming from the mountains, we is use to a wash pan and a tub for cleaning up. We has a half-way sort of a little water privy in the kitchen closet, but it don’t flush right. I can tell you, though, it beats trotting out in the back yard in the weather.

“The last of the three rooms we has is damp and cold without you keep a fire going all the time. And we can’t do that. The basement’s about all that’s brick about the whole house. That’s the reason our rooms stays that way. The house up above us is in awful shape. The roof leaks. It lets the water all over the kitchen floor. I just reach the broom out. I keep sweeping it to the back door. The walls stay so wet half the time that wallpaper just pops off everywhere.

“... I guess we can’t expect just a whole lot for the rent we pay. The landlord never misses coming a Monday for our two-fifty. But fixing things up is another tale and it’s never told. He won’t do a blessed thing about this wetness and it matters not how much we howl. Tells us now that the government is planning to tear down every house in the block and put up some sort that ain’t tenements. Well, ’twon’t be no trouble to tear down. Just give a push, and not such a hard one either, and the last one of these houses will come down and never a wrecking tool needed to help out.

And the neighborhood is worse and far worse than the houses. Oh, I know it’s no place to bring a youngin up at all. I thank the Lord that me and Calvin has got but only the one, and that’s Cap. We can manage him all right with both of us studying on it. Most of the families in this block has from six all the way to ten youngins, and all sizes. Seems like about half of the mothers is sick. They just let the youngins run around as filthy as cow-dab. I tell you, most of these youngins learn to cuss and swear and take the Lord’s name in vain when they’s buggers of five years old and less. They start fighting amongst one another. Before long the ma’s and pa’s take sides. It ends in a cutting scrape or one or the other taking their leave of the street. Me and Calvin stays clear of it all.

“...Calvin gits plenty of work here in Knoxville. He works cheap and that’s the reason, I guess. He’s not what you’d call a skilled worker. But he can do as good work as the best of them, I don’t care what name you call them by.

“They’s more folks here in Knoxville that wants cheap repairing than any other kind. The rich folks is the same way. Calvin knows where he can git supplies cheap. He can take a contract lower than most and still come out on top. If he could just go straight from one job to the next, why I bet he’d make close to twenty dollars a week. Like things is now, he makes about ten. He loses money looking for jobs and figgering on gitting things in shape to git the contract. Old customers has always stuck to him. But things ain’t going to keep dropping to pieces about the same folks’ house if they’s fixed right. And Calvin always fixes them right. Sort of cuts his own throat, but he does it.

“I do all the washing and ironing and cleaning and cooking. And I can stretch that ten dollars out for the three of us. Rent and coal and kindling and food eats up about seven of it. That leaves three for other things and the clothes we wear. It don’t take no more than fifty cents a day to feed the three of us. We’s country folks. Glad to git corn bread and beans and potatoes and greens. I’ve heard some doctors say you could live on corn bread and vegetables without meat. I doubt it. Not and be hardy. I try to git meat for us at least twice a week. Fix an egg for us at breakfast. I pay a nickel a day for a pint of milk for Cap. I know he ought to have it, a growing boy like he is. We never had to spend a red cent on doctors’ bills for no one of us. Not even when Cap come. It didn’t cost me nothing because the midwife was a friend of mine. She wouldn’t hear of me paying her for helping me through.

“Me and Calvin wasn’t only thinking about easy going for our own selves when we come to Knoxville. We knowed Cap would have a better chance at schooling here. And do you know what? That boy ain’t turned sixteen yet and here he wants to quit school and go to work. Some ways I don’t blame him. As hard as we work it looks like it just never is anything left over for us to throw to him to spend for fun. And they ain’t a soul lives around here I care for him to run with. Well both me and Calvin carries burial insurance. It’ll git us out of his way without cost if anything happens to us. I don’t see no sense in paying out for that on Cap yet. He’s not going to die no time soon. If he’s going to start out for hisself, I want him to have some sort of a good job. He can have every penny he makes for hisself, too, I don’t belief in milking your children.

“I told him it’s got to be some good straight job. Some boys git it in their heads that they can make a sight of money selling liquor. The law cracks down on them almost as soon as they git a start. We see it happen every day around here. You’ve got to keep the law paid off a good and plenty or else the penitentiary is where they’s going to land. Now if they does pay off, where is the profit left from selling? Ain’t none. So there they is. I told Cap if he had it in his head to do that, he better be clearing his head of it right now.

“I don’t blame him one bit for having his mind set on making a little money to have fun on. Seems like me and Calvin ain’t never done a thing ever but work hard all our lives. Some folks find pleasure in going to meeting on Sunday. But it’s no church I’ve had sight of here in Knoxville where the ones coming in and out ain’t dressed up fit to kill. Some says it’s all the same in the eyes of the Lord about how you dress. But I knows if He’s got sense at all, he knows our clothes is too wore out for Sunday strutting. I know they’s shabby in my own sight.

“Calvin and me both can read right well. In times back we use to read the Bible pretty much. But seems like you always come across something you can’t make out straight. So we just stopped reading it. Looked a pure shame, as wore out as we was to read things that upset your head.

“I guess I got on to the main of it, though. I know that Jesus Christ died to save sinners. And all that me and Calvin have to do is trust in Him. And we do. And we believe on Him. I don’t see where they’s any way to keep me and Calvin out of Heaven.”

Tags

Tom Terrill

Tom E. Terrill is associate professor of history at the University of South Carolina at Columbia. (1978)

Jerrold Hirsch

Jerrold Hirsch, a PhD candidate in history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is working on a study of the Federal Writers’ Project. (1978)