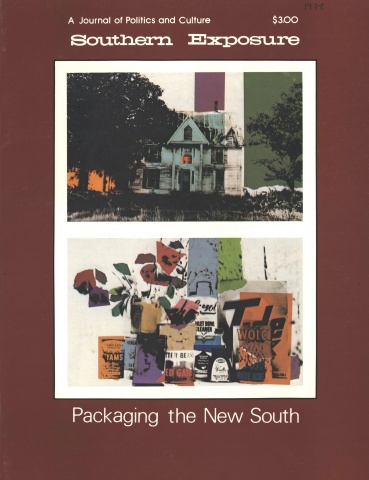

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 1, "Packaging the New South." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Calloway School is in eastern South Carolina, near a marshy, moss-hung river, and surrounded by miles of straight pine trees. It’s past the Wando Lounge and Poolroom, past small clapboard “shotgun” houses, beyond Carter’s Grocery where the kids sneak out at lunch to buy “a soda and a candy,” and the Dynomite Social Club where there is dancing, drinking and sometimes violence on Saturday nights.

The school has no yard to speak of. Grass is sparse, and the dust turns to muck in the rain. It is a long brick building with clumps of trailers scattered around the back. Calloway is an almost all-black school; only two white children were in the elementary grades the year I taught there.

Although the number of miles is the same, Calloway is farther from me now than it was two years ago when I drove the long road out and back, more often than not crying all the way home. It was my first year of teaching. I didn’t know what to expect. As I was to learn (a lesson that lurked around every corner waiting to whap me over the head), it was best to expect nothing.

The principal, Rev, hired me to teach BRL. I didn’t know what that was. I was to receive training but never did, aside from an odd workshop on human relations.

Then, on the first day came another surprise — I had no classroom. I went to Rev. “Oh yeah,” he said in his slow basso, looking at the ceiling. “Well, what we’re going to do is have you and Miss Wetherington team teach.”

Miss (Dody) Wetherington refused. She wasn’t about to have forty or fifty kids in one tiny trailer, and I agreed with her. So for three weeks, I “taught” on the football field (being eaten by mqsquitos, in the gym (competing for attention with the basketball practice), in the lunchroom (smelling lunch cooking). At first there were no textbooks — they trickled in all fall. My last class finally received their English books in January. The problem was not money; books were free for my classes. The problem was that the assistant principal ran out of them and didn’t reorder for months.

So we tried without books. It was hard. At the beginning of the school year there was the usual profusion of supplies, but this newness wore off. “I ain’t got no pencil,” they’d say. “You got a pencil? Who got a pencil? I ain’t got no paper. You got a paper?” Kids would fight over a pencil. I spent at least two hundred dollars during the year on pencils, pens, word puzzles, books, Scrabble games and so forth.

Finally the county sent us a trailer. Its ceiling was falling in and there were no steps. We moved in anyway, and for several weeks workmen were in and out of the makeshift classroom, hammering and drilling, giving it electricity that sometimes worked, heat that failed about one day a week during the winter. I suppose they tried to fix the roof, but every hard rain there were two huge puddles; we arranged the desks around the leaks.

Except for a few desks, we had folding chairs that had been at the school since 1956. I scraped and scrounged and dug up almost enough desks. I practically stole some bookshelves. We worked like movers. We mopped. Though Rev always assured me that the trailer would be mopped and swept, it was swept only when I did it, and mopped twice, by me, once when we moved in and once when we got the school ready for the PTA Open House. And so I learned my second lesson. MAKE DO. And don’t trust the principal or the county administrators to get anything for you. I saw that my very classroom, teaching materials, everything, depended on me.

BRL turned out to be a programmed text reading lab. The kids hated it because the Dick-and-Janeness of it hurt their pride. “Sheeeeeut!” they’d say. “We have that stupid little book last year.” And they firmly refused to do it. I was to struggle with BRL all year. After three months, 9-C, my class of all boys, some non-readers, finally admitted that they were working above their heads, gave up the farce and went back to Book One or Two. Until then, I hadn’t been able to get past their pride — they wouldn’t admit that they couldn’t read. And I couldn’t force them.

Calloway kids were already under so many stigmas that it was almost impossible to boost their egos enough to motivate them to learn. They were homogeneously grouped in homerooms according to their “ability,” 7-A, 7-B, et cetera, and stayed in the same homeroom all through high school — only the numbers changed. It took nearly an act of God to get a child transferred to a different level.

My teaching methods varied. Authority never worked. They balked at anything you told them they had to do. I tried appealing to their pride. “Don’t you want to learn?” “Yes, but not now.” “Well, then what do you want to do?” “We want to go outside, have a free day, go to the store.” I’d get angry, lose my voice, stomp and cry in sheer frustration.

Structure worked. But you had to get the worksheet into their hands immediately; they didn’t listen to directions. I’d give them the work and then go to them individually, showing them how to do it.

Love also worked. To love and respect the children no matter what they did or didn’t do was something I learned from two other teachers. Eventually I began to get these things back from the kids. After a while, all my classes were good but one. 7-A was made up of bright, precocious kids who had been together since the fourth grade; they gave every teacher trouble. They were my homeroom and last period class so I started and ended the day with their singing, stomping, beating the desks, playing in the closet — their high energy and defiance.

Discipline at Calloway was administered in two ways. A misbehaving student was either sent out of the class and made to pick up trash on the school grounds, or whipped, usually on the hand, with a strip of tire rubber. They loved the first punishment. They got out of class, they were outside and they could come around the trailer and leer through the windows at their less fortunate friends inside. Unknowingly, I sent two students to the office that first week that we had a classroom. They missed the next two days of classes. When I asked that they be allowed to return to take a vocabulary test, the assistant principal agreed. Instead, they skipped the test and ran around the trailer all period. I raised hell at a faculty meeting about the uselessness of our disciplinary measures. But detention was out. We couldn’t keep them after school because some lived twenty miles away. So discipline was non-existent as far as the administration went. We had to handle it ourselves.

Here’s an excerpt from a letter I wrote in October:

Today was horrible. I was dizzy all morning, don’t know why. Some of Sally Smith’s students urinated all over her classroom during lunch today. The reason is that she shares the room with Bill Akerson (i.e., two classes going on at once because she is a new teacher too, and has no classroom, like me, for the first three weeks), a thoroughly incompetent teacher and repulsive person. He’s white — the kids hate his guts and it tends to prejudice them toward other white teachers. This guy can’t handle the kids at all (especially 7-A) so he just beats them with a strap or sends half his classes to the office every period. The kids who did this were doing it against him, but poor Sally has to suffer. Two days last week and one this week, my trailer had no heat. Which means no teaching. Dody’s is not working either. They can’t pay attention when they’re cold. I tried writing on the board with gloves on. It gets progressively worse as I find out more things, and have normal expectancies crushed. I was to receive folders for my kids but they haven’t come. Also grades were supposed to go out two weeks ago Friday but we have no report card folders, and I hear today that we’re going to switch over to the nine-weeks system which will be just dandy. Maybe an easy transition in another school, but in an organization like Calloway, it will take all year.

The problem is not the children and never was. The problem is the horrible school they have to attend and the system that keeps it that way. Teachers like Akerson were rehired. He was not the worst. There was Rev. Jenson, who had three jobs: he taught history at Calloway, worked at the docks at night and preached in a town eighty miles away. So he slept in class. If the kids woke him, he beat them with a two-by-four.

There was Mrs. Jones. I could always tell which of my classes had just been with her because they would come in sullen, hating and resenting me. She filled the kids with propaganda, telling them not to trust white teachers. Mrs. Jones got into trouble with Rev once for passing two failing girls because they had sewn her a pants suit. But apart from that, no one supervised either Jenson or Jones. They were both kin to Rev.

I alternated between bitterness, frustration, helplessness, rage at Rev, rage at the county, utter depression, and sorrow for the predicament of these children. Finally, some of the other teachers and I took action. We started making phone calls, writing letters. We went to board meetings — white school board, black parents. In my notes from one meeting, I wrote: “The superintendent is very explanatory about the ‘problems’ he faces. He’s good at letting ‘you people’ know such things as ‘expenses are going up; it takes a lot of money to run our schools, much less make repairs.’”

Indeed. School money doesn’t exist in Banks County because property taxes are exceedingly low. The reason is obvious: many of the legislators own large tracts of land and they won’t tax themselves. One high school of affluent, middle-class, mostly white students formed its own school board to raise funds and decide policy.

We wrote a list of grievances to the school board, including such things as unusable bathrooms, lack of materials, a deteriorating physical plant, lack of organization (bells never rang, schedules went haywire, there was no communication by principal with teachers), arbitrary promotion of students, and the rehiring of incompetent teachers.

All that happened was that Rev was fired. Or rather, he resigned, effective the end of the term. Of course, he took it personally, and his last few months were ones of vengeance against the teachers who had complained to the board.

My memory is haunted by two events of the spring that I doubt I can ever efface. I took my classes on a field trip to the museum in Charleston. That is, all my classes but 7-A. They had been unruly for three weeks, and had done no work. When we returned, the classroom had been turned upside down. Books were strewn all over the floor, some torn in half; all my desk drawers were emptied; the bulletin board was ripped down.

7-A remained obstinately bad through the last week of school. No one was clear about the exam schedule. Although Rev had scheduled exams to last three days — Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday — he also told us that final report cards were to be handed out in homeroom Tuesday morning. You figure it out. We tried and never succeeded. Plus, students who still owed money in fees were not to receive their report cards at all.

Tuesday morning, 7-A gathered around me. Report cards were very important to them. I called the names, but kept the cards of those students who owed money, and told them how much was- due. Most of 7-A owed fees. They protested, more and more loudly, and crowded around, yelling and fussing. One boy snatched his report card from my hands. Another threw a book at me and it hit me in the head. They slapped the report cards to the floor. They punched and hit me.

As I bent to retrieve the report cards, somebody pushed me to the floor. “Oh look at that lady! Heeeee, hee hee! She fall down.”

I ran. They followed me, yelling taunts and insults. Laughing. I ran to the car, hysterical, rolled up the windows and locked the doors. Kids crowded around to see what was the matter. One or two came up with appeal written on their faces, and knocking on the glass, pleaded with me: “Please, Miss, I didn’t, I didn’t do anything. Them children bad.”

I sobbed and shook for hours, and now, as I allow myself to recall this, I cry again.

I never returned.

The good times I had with my kids are almost overpowered by that blinding memory. But some images stand out like the big yellow letters that spelled LANGUAGE on the collage we made across one wall of the trailer. Like Elaine’s poem: “If I die bury me deep. Lay a book upon my feet. Tell Miss McLeod I gone to rest. But I be back to take her test.” And the image of the time 1 watched the same sweet girl flinch as she received five licks on her palm from Rev. I see myself telling June, “You’ve gotten so tall!” and her reply, “How high I get?” Jackie saying, “You give us a little minute to study?” And David saying, “Miss McLeod, it’s a good thing you got a boyfriend.” “Why, David?” And Joe answering, “Cause David, he be tap dancin in yo’ heart!”

There was Ventphis and his Star Trek script that would rival any on television. Marty, the eighth grader from New York with an IQ of 150, explaining to me the feminine quality of the sea and the old man’s lover-like relationship to her. Benjamin’s answer to the question, “What do you want to learn?”: “I want to learn everything there is.”

Finally, a letter from one in 7-A:

Miss McLeod I am sorry for the way I act in your class but I think the devil make me do that but He ain’t going to do that no more. When you took the children on that trip and when you get back the class was mess up but you think we did it but we didn’t. I am tell you the truth. I am afraid I might not pass. I just get two books from you and that’s my math and language. I didn’t get no social studies, spelling, science. I am closing my letter but I am not through away my love I got for you Miss McLeod. I just want you to remember m, remember e, but most of all, remember me. Love ya, love ya, I hope you love me, Adell.

There remain some hardworking, dedicated teachers at Calloway. And a few things have changed. The new principal is doing a better job, although at first he was as incapable as Rev. The building looks better because the parents worked hard for six consecutive Saturdays, cleaning and painting the entire inside. But I doubt that the county will ever go so far as to build a new school.

And the worst teachers, Rev. Jenson, Mrs. Jones and the assistant principal are still there, the first still falling asleep, and the second still poisoning the kids’ minds.

I miss those kids, their innocence, their decency and manners, their pureness of feeling. Avis reminds me. I haven’t forgotten. Calloway is far away for me now. But the children are still there.

Tags

Harriet McLeod

Harriet McLeod is currently living on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina. Though the names of the people and the places in this article are fictitious, Harriet McLeod is relating her own experience. (1978)